Warner Brothers/Getty Images

I broke its neck.

When making a vase at the potter’s wheel, I torqued its slippery neck clear off the pot as I tried to thin it into a graceful curve.

I find vases gratifying to make and their shapes especially pleasing to the eye. But vases also must be handled with particular care because one part of their “body” – the neck – is often so narrow that it can be easily broken.

That day at the wheel, I realized that it was not unlike the human neck. Though only a small portion of the human body – about 1% by surface area – our necks have an outsize influence on our psyche and culture.

From selfies to formal portraits, the neck positions the head in expressive poses. The neck’s vocal cords vibrate to make meaningful words and moving songs. We passionately kiss it and spritz it with alluring perfume. We use it to nod our head in agreement, tilt our head in confusion and bow our head in prayer.

Ornaments such as necklaces can express fashion sense as well as signal wealth and status. Collars can accent the face in portraits as well as denote occupational class, blue collar versus white collar.

Yet, for all its aesthetic and expressive potency, the neck is also a site of fear and deep vulnerability. Villains and vampires zero in on the neck. Stressful days at work make us clench our neck muscles until they ache. A pleasant meal can be jolted into terror if a morsel slips into the wrong tube in the neck, sending us into a coughing fit.

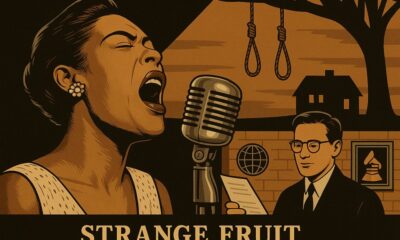

For millennia, people in power have oppressed their subjects by exploiting the narrowness and fragility of the neck – a dark history of dominating and terrorizing one another using shackles, nooses and guillotines. The widely circulated video of George Floyd’s murder was a brutal reminder that violent asphyxiation is hardly confined to the distant past.

As I became aware of the significance of the neck in culture, I began to explore how these two attributes – its expressive vitality and unnerving vulnerability – could coexist and be concentrated so intensely in one small region of the body. Eventually, it became a book.

I am foremost a biologist, and in writing my book, I came to see that the neck’s vitality and vulnerability are rooted in its biology: The neck performs an especially wide variety of crucial functions, and it is the product of a quirky evolutionary history.

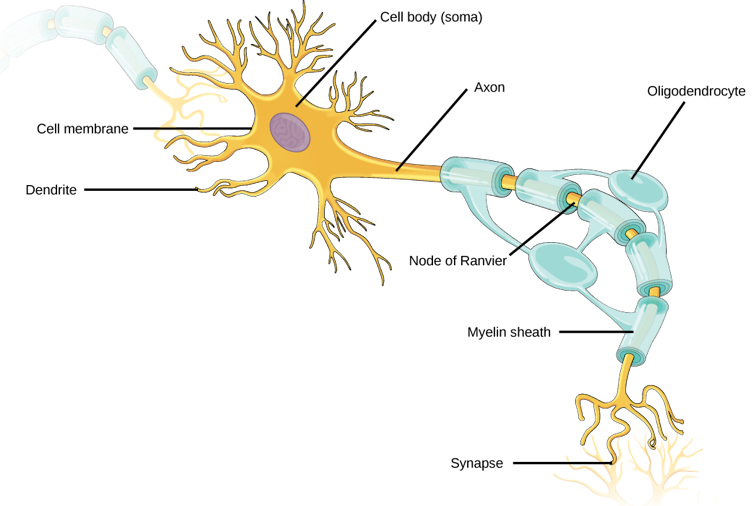

The neck does so many things, all at the same time. For example, it transports over 2,000 pounds (907 kilograms) of blood, air and food between the head and the torso every single day. It moves the head every six seconds on average to direct our visual attention. Its vocal cords vibrate hundreds of times per second with every spoken word.

But this multifunctionality, this vitality, is possible only because of its vulnerability. To be mobile and flexible, the neck must be narrow, and so it is easily strained. Its crucial transport tubes – the windpipe, esophagus and blood vessels – must also be thin and near the surface, making them easily punctured and compressed.

From water to land

Our vertebrate ancestors “invented” this peculiar contraption as they evolved from water to land.

Our fish ancestors had no neck because they needed a single rigid axis to move efficiently through water. Since moving around on land did not require a stiff spinal column, early terrestrial vertebrates evolved flexibility just behind the head, enabling them to widely scan the environment and to direct their mouths toward prey without moving their whole bodies. Picture a zebra swinging its head side to side surveying the savanna for predators, or a lizard tilting its head down and to the side to snap up a crawling bug.

National Gallery of Art

Early land vertebrates also evolved lungs, and this transformation freed up the gill structures that fish used for breathing to evolve into various useful – and sometimes problematic – neck structures, such as the voice box, tonsils and the little flap that separates the windpipe and esophagus.

This repurposing of scraps left over from the gills of our distant ancestors contributed to the diverse capacities of our neck. But as products of a quirky evolutionary “renovation,” humans and other land vertebrates live with a jerry-rigged design that fates us to carry many collateral vulnerabilities at the neck.

The peculiar human neck

While the human neck retains the basic design of our ancestors, it’s nonetheless quite unusual among vertebrates.

Most land vertebrates elevate their bodies on four legs, so their necks must be long enough to lower their heads to the ground to feed and strong enough to raise it up high to look around. Again, think of a zebra feeding on the savanna.

Because humans walk on two legs, we balance our head atop our spine. Since we use our hands to grab our food, we don’t need strong neck muscles to move the head around. So, compared with most mammals our size, our necks are relatively weak, making them more prone to strain and injury.

As another milestone in human evolution, the voice box migrated to a relatively low position in the neck, and this unusual placement contributes to our capacity to make an especially broad range of vocal sounds that we use for speech. However, this descent of the voice box within the throat also makes us more susceptible to choking and sleep apnea.

The neck epitomizes the dual nature of the human condition, the ways in which beauty and frailty are often entwined, two sides of the same coin in our biology, in our relationships – and, yes, even in ceramic vases.![]()

Kent Dunlap, Professor of Biology, Trinity College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.