Sean Gladwell/Moment via Getty Images

Aliasger K. Salem, University of Iowa

Biomedical research in the U.S. is world-class in part because of a long-standing partnership between universities and the federal government.

On Feb. 7, 2025, the U.S. National Institutes of Health issued a policy that could weaken the position of the United States as a global leader in scientific innovation by slashing funds to the infrastructure that allows universities and other institutions to conduct research in the first place.

Universities across the nation carry out research on behalf of the federal government. Central to this partnership is federal grant funding, which is awarded through a rigorous review process. These grants are the lifeblood of biomedical research in the U.S.

When you think of the costs of scientific research, you might picture the people who conduct the research, and the materials and lab equipment they use. But these don’t encompass all the essential components of research. Every scientific and medical breakthrough also depends on laboratory facilities; heating, air conditioning, ventilation and electricity; and personnel to ensure research is conducted securely and in accordance with federal regulations.

These critical indirect costs of research are both substantial and unavoidable, not least because it can be very expensive to build, maintain and equip space to conduct research at the frontiers of knowledge. The NIH stated that it spent more than US$35 billion on grants in the 2023 fiscal year, which went to more than 300,000 researchers at more than 2,500 universities, medical schools and other kinds of research institutions across the nation. Approximately $9 billion of this funding was allocated to indirect costs.

NIH grants have supported the direct costs of my own scientific research on developing treatments for conditions ranging from cancer to eye diseases. I would be unable to carry out my research without the support of the indirect costs the NIH plans to cut.

What are indirect costs?

Indirect costs, also known as facilities and administration costs, or overhead, are funds provided to institutions to cover expenses that are not directly tied to specific research projects but are essential for their execution. Unlike direct costs, which cover salaries, supplies and experiments, indirect costs support the overall research environment, ensuring that scientists have the necessary resources to conduct their work effectively.

Indirect costs include maintaining optimal laboratory spaces, specialized facilities providing services like imaging and gene analysis, high-speed computing, research security, patient and personnel safety, hazardous waste disposal, utilities, equipment maintenance, administrative support, regulatory compliance, information technology services, and maintenance staff to clean and supply labs and facilities.

Research institutions that receive federal grants must comply with the rules and regulations established by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget. These guidelines dictate the indirect cost rates of each institution.

Institutions submit proposals to federal agencies that outline the costs associated with maintaining research infrastructure. The cost allocation division of the Department of Health and Human Services reviews these proposals to ensure compliance with federal policies.

Indirect rates can range from 15% to 70%, with the specific level depending on the research and infrastructure needs of an institution.

Typically, institutions undergo an exacting process to renegotiate their indirect rates every four years, factoring in components such as general, departmental and program administration, building and equipment depreciation, interest, operations and maintenance, and library expenses. Universities need to carefully justify these cost components to ensure the sustainability of research infrastructure and compliance with federal requirements.

Notably, indirect costs from grants do not cover the full cost of carrying out research at universities. In 2023, colleges and universities contributed approximately $27 billion of their own funding, such as money from their endowments, to support research. This included $6.8 billion in indirect costs that the federal government did not reimburse.

Slashing vital research funding

In its February announcement, the National Institutes of Health declared that it would no longer determine indirect costs rates based on the needs of each institution. Instead, it would issue a standard indirect cost rate of 15% across all grants. The rationale given by the agency for the cap is to “ensure that as many funds as possible go towards direct scientific research costs rather than administrative overhead.”

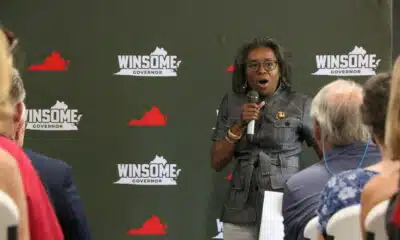

It notably comes after the Trump administration and Elon Musk have sought to slash federal spending, with Musk criticizing indirect cost rates as “a ripoff.”

A standard 15% rate would significantly affect an institution’s ability to maintain its research infrastructure. For example, if a university had a 50% indirect cost rate in 2024, it would receive $150,000 for a $100,000 grant, with $50,000 allocated to indirect costs. With the new NIH cap, this would drop to $115,000, with only $15,000 for indirect costs.

The scale of this cut in research support becomes apparent at the state level, with harms to both red and blue states. For example, Texas institutions would face a reduction of over $310 million, and institutions in Iowa a reduction of nearly $37 million. California would lose more than $800 million, and Washington over $178 million.

David Ryder/Stringer via Getty Images News

The NIH compared the new 15% cap to the indirect cost rates that foundations typically set for institutions of higher education. It pointed to the 10% rate granted by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Smith Richardson Foundation, the 12% rate of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the 15% rate of the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, John Templeton Foundation, Packard Foundation, and Rockefeller Foundation.

However, many researchers and funders have criticized this claim as misleading. A spokesperson for the Gates Foundation has previously stated that the listed rate does not reflect how the organization allocates its funds. Universities have pointed out that they often accept foundation grants with low or zero overhead rates because these grants constitute a relatively small portion of their funding and are often spent on early-stage faculty whose careers need additional support.

In addition, it is only because NIH grants cover a significant portion of their overhead costs that research institutions are able to accept foundation grants with such low indirect rates.

Biomedical researchers respond

Scientists and researchers responded to the NIH announcement with deep concern about the negative effects these funding cuts would have on biomedical research in the United States.

The Council on Governmental Relations, which monitors federal policy for major universities and medical research centers, stated that “America’s competitors will relish this self-inflicted wound,” urging the NIH to “rescind this dangerous policy before its harms are felt by Americans.”

The president and CEO of the Association of American Medical Colleges stated that the NIH policy would “diminish the nation’s research capacity, slowing scientific progress and depriving patients, families, and communities across the country of new treatments, diagnostics and preventative interventions.”

Research institutions, scientific societies, advocacy groups and lawmakers from both major political parties have pushed back against the 15% cap on indirect costs, urging NIH leadership to reconsider its policy.

Soon after the attorneys general of 22 states filed lawsuits challenging the policy, a federal judge issued a temporary pause in those states until lifted by the court.

Scientists expect the long-term effects of these funding cuts to significantly damage U.S. biomedical research. As the debate over federal support to academic research institutions unfolds, how institutions adapt and whether the NIH reconsiders its approach will determine the future of scientific research in the United States.

Aliasger K. Salem, Bighley Chair and Professor of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Iowa

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.