Mississippi Today

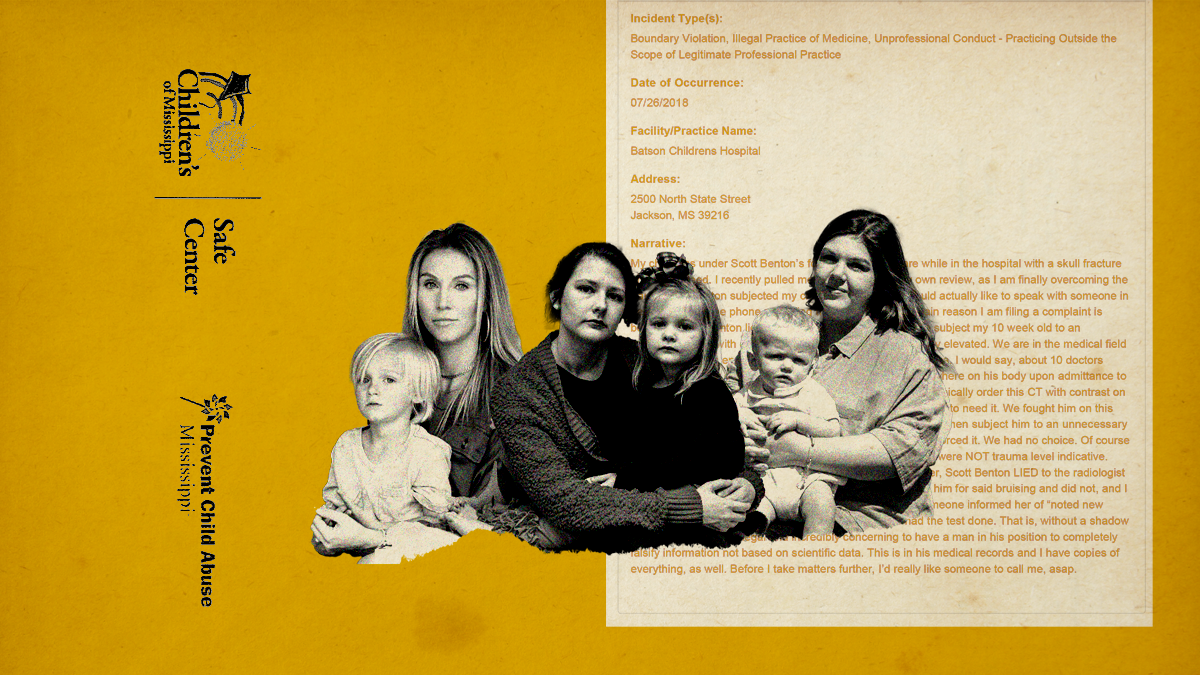

How Dr. Scott Benton’s decisions tore these families apart

How Dr. Scott Benton’s decisions tore these families apart

This story is the third part in Mississippi Today’s “Shaky Science, Fractured Families” investigation about the state’s only child abuse pediatrician crossing the line from medicine into law enforcement and how his decisions can tear families apart.Read the full series here.

Caryn Jordan, Columbia

When Caryn Jordan took her 10-month-old daughter to Forrest General Hospital on March 29, 2020, she never imagined the state would take her child from her.

She said she also never considered that a pediatrician who would accuse her of child abuse wouldn’t do the necessary testing to determine if a genetic disease caused her daughter’s fractures.

The nightmare started when Jordan was putting her daughter Sawyer in her high chair. She noticed one leg was warm and swollen. She tried to get Sawyer to stand up, but the child couldn’t handle pressure being applied to the swollen leg.

At Forrest General Hospital, Jordan said doctors told her an X-ray revealed a fracture on Sawyer’s leg and that the hospital would have to transfer Sawyer to the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC) in Jackson because they were not equipped to put a cast on an infant. The hospital had contacted Child Protective Services, she said she later realized.

An official with Forrest General Hospital said when there is suspected abuse or neglect, the hospital social worker is consulted and further screening is done.

“CPS is notified when circumstances warrant,” said Suzanne Wilson, the director of emergency services and transfer center at the hospital.

Wilson said not all suspected abuse cases are transferred out of the facility, but those requiring a specialist’s care are transferred, as well as those in need of pediatric services not provided at the hospital.

After performing a full body X-ray on Sawyer at UMMC, doctors told Jordan her daughter had a broken leg and 11 fractures across her body in various stages of healing.

Jordan was baffled. Sawyer had rarely left their home, aside from frequent doctor visits due to stomach issues and a salmonella infection. Her mind raced for answers.

Then Jordan got a call from Dr. Scott Benton, a pediatrician at UMMC who specializes in child abuse pediatrics. He told her that Sawyer looked like she had been thrown against a wall or in a car accident, she said. Another mother told Mississippi Today that Benton also accused her of throwing her baby against the wall.

“He spoke to me like I was this abusive, disgusting mother,” Jordan said. “I don’t think I’ve ever been that angry.”

Benton, who Jordan said she never saw in person, determined abuse caused her injuries. Jordan said to her knowledge, Benton, who told her on the phone he was out of town at the time, never saw Sawyer in person.

Jordan would not be taking Sawyer home. She was told to leave the hospital, and Sawyer went into the custody of Child Protective Services.

Back home in Columbia, Jordan turned all of her energy into getting Sawyer back, a fight that cost her everything. She was only able to work part time due to frequent court dates and doctor’s visits. She drained her savings and lost her health insurance. Her relationship with her boyfriend imploded. She moved back in with her parents.

“Could the fractures have occurred during birth?” she wondered. At one point, Sawyer got stuck in the birth canal. She had to be pushed back inside and delivered through an emergency cesarean section, Jordan said.

“Might Sawyer have a brittle bone disease called osteogenesis imperfecta?” Jordan thought. The group of inherited genetic disorders affects how the body makes collagen and causes fragile bones. A Facebook group she joined for parents whose children had the disorder encouraged her to request a bone density test.

But when Jordan proposed the idea, Benton replied in text messages that she shared with Mississippi Today: “There is no validated and approved bone density test for infants.”

While bone density tests are not typically performed on infants, there are alternative methods, Jordan said a pediatrician at Children’s Hospital New Orleans told her in June 2020. They include a skin biopsy or genetic testing to look for anomalies in certain genes involved in encoding collagen.

In videos shared with Mississippi Today, the New Orleans doctor tells Jordan that Sawyer’s symptoms and injuries are consistent with what is seen in a child with brittle bone disease, and that often the fractures are painless and left undiscovered for some time.

But Jordan was unaware Benton had performed a genetic osteogenesis imperfecta panel test on Sawyer on March 31, nor was she given the results. That test detected a variant of uncertain significance in her COL1A1 gene, which is involved in collagen production, according to Sawyer’s medical records from UMMC.

Dr. Mahim Jain, director of the Osteogenesis Imperfecta Clinic at Kennedy Krieger Institute and an assistant professor in the Department of Pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, said issues with the COL1A1 gene are a major cause of OI.

“A variant of uncertain significance doesn’t really say, ‘Yes, it is disease causing’ or ‘no, it’s not.’ It means that there’s more work to be done to try to sort out if it is causing the condition,” Jain told Mississippi Today.

Benton’s report on Sawyer’s genetic test recommends genetic counseling and targeted testing of her parents to better understand the implications of this variant, but no further testing was done and no explanation was given as to why, according to the medical records.

Jordan said she became aware of the test and its results only after her case was concluded.

Benton declined to answer questions about Jordan and her daughter’s case, even though Jordan submitted a form to UMMC authorizing hospital employees to discuss her daughter’s medical records with Mississippi Today.

Benton told a group of public defenders in a recorded presentation about sex crimes, however, that before he came to UMMC in 2008, parents and anyone who was suspected of being associated with a child’s injury was “kicked out of the hospital.”

He said he reversed that policy so he could be sure to get a full history from parents and not overlook any possible medical explanations for a child’s injuries.

“That was part of their protocol (at the time). And I said ‘Alright, who am I supposed to get the history from? Who am I supposed to (talk to) to figure out if there’s a medical explanation for some of these bleeding findings?’” he told the group. “So we quickly reversed that.”

For the first three months while Sawyer was with a foster family, Jordan said she wasn’t allowed to see her, despite CPS visitation policy that states contact between the child and his or her parents must be arranged within 72 hours of that child being placed into foster care.

Shannon Warnock, a spokeswoman for CPS, said the agency can’t comment on specific cases, “including any exceptional circumstances that warrant policy adjustments.”

In December 2020, nine months after Jordan went into CPS custody, Jordan’s parents got a foster care license and got custody of Sawyer.

In doing so, that meant Jordan had to move out. She found a one-bedroom apartment she could afford.

Ultimately, the youth court judge concluded Sawyer was abused but it was unclear who inflicted the injuries, so she was returned to Jordan on April 5, 2021.

In the aftermath, Jordan has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, an anxiety disorder and depression. She mourns the milestones she missed during the 15 months Sawyer was taken from her.

“I missed my daughter’s first birthday,” Jordan said. “I missed her first Easter. I missed her first step. I missed a lot of firsts. And these are things I can never get back.”

The separation also affected Sawyer, now an outspoken 3-year-old who sometimes rolls her eyes at her mother and loves to dance.

Sawyer has to carry KeKe, a fuzzy blanket covered in llamas, with her wherever she goes, Jordan said. The baby blanket was the only one of her belongings she was able to keep while in state custody. She still has separation anxiety, and Jordan often has to reassure her she will not leave her again.

Jordan recently scheduled additional testing for Sawyer in New Orleans to confirm if she has the brittle bone disease. She said she waited because of the cost, and because for a long time, the idea of taking Sawyer to a doctor left her terrified.

The two now live in a two-bedroom house in Columbia with a large backyard. They’re trying to start over and create a new normal.

“Ever since they closed our case, I’ve just tried to be a mom,” Jordan said.

Lindsey Tedford, Tupelo

Lindsey Tedford of Tupelo rushed her 3-week-old son Cohen to the local emergency room at North Mississippi Medical Center on June 13, 2021. While her husband was holding their newborn and bent down to pick up a pacifier from the floor, Cohen had hit his head on the nearby crib, the parents told the nurses in the emergency room.

Cohen had bruising under both eyes and on his nose but was otherwise fine, the doctors told her.

The hospital never performed CT or MRI scans, medical records from the visit show.

But when Cohen was at a pediatric cardiologist appointment about two and a half months after the crib accident, the doctor noticed something concerning. Cohen’s head circumference had increased since his two-month checkup with his pediatrician. He scheduled an ultrasound two weeks later, and the results were “concerning for a brain bleed,” according to the baby’s medical records.

The doctor sent them to the North Mississippi Medical Center for a CT scan. It confirmed the ultrasound results: Blood had collected between the skull and the surface of the brain, and Cohen had a possible skull fracture.

The results triggered a chain of events that led to the Tedfords losing custody of Cohen for nearly five months. The state’s only child abuse pediatrician, Dr. Scott Benton, accused them of child abuse and diagnosed Cohen with “nonaccidental trauma.”

In recent months, doctors at Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital in Memphis have diagnosed Cohen, now over a year old, with a bleeding disorder called idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, or ITP. Subdural hematomas and intracranial hemorrhage — both diagnoses Cohen received at UMMC — are rare complications of ITP.

Back in September of 2021, the North Mississippi neurosurgeon recommended operating on the brain bleed as soon as possible. Lindsey asked the doctor to transfer Cohen to Le Bonheur in Memphis and left the hospital to go home to get clothes for the trip. On her way back, she got a frantic call from her husband Blake: they had taken Cohen in a helicopter, and he didn’t know where they were taking him, she said.

“As soon as Blake left to go out of the room to follow the people taking Cohen to the helicopter, (people from Child Protective Services) were waiting on him to question him.”

Eventually a nurse manager told him Cohen was sent to the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, she said.

A spokeswoman for North Mississippi Medical Center said the hospital aims to care for potential victims of child abuse “with love and respect.”

“We report child abuse to Child Protective Services in accordance with Mississippi regulations and treat as medically appropriate,” the spokeswoman said when asked how the hospital handles cases of suspected abuse and neglect. “UMMC maintains a Pediatric Sub-Specialty Clinic in Tupelo, which offers non-traumatic medical examinations and treatment for cases of suspected abuse and neglect.”

The Tedfords said they made phone calls to UMMC as they drove to Jackson. They eventually found Cohen in the emergency room.

They didn’t hear from Child Protective Services again until almost two weeks later — the day before Cohen was discharged into CPS custody.

CPS policy and state law do not require parents be informed they are being investigated for possible child abuse in any specific time frame.

“The Foster Care Policy manual does say that a parent ‘will be notified prior to, or as soon as safely possible, that his/her child is being placed in custody,’ but there is no specific time period for notifying the parent of the child’s removal,” said Shannon Warnock, a spokesperson for CPS.

She said the agency could not comment on specific cases.

Following more tests, Cohen was transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit. Neurology, hematology and ophthalmology consulted on his case.

Blood work revealed he was anemic, but medical records note a hematologist “… felt that anemia was most likely secondary to subdural hematoma.”

No other tests or scans were abnormal, according to the records.

About five days into Cohen’s hospital stay, Dr. Scott Benton introduced himself to her and her husband as the “staff forensic pediatrician,” Lindsey said.

“I didn’t know what that meant,” she said. “He said, ‘I’m going to record this session,’ and didn’t tell us a whole lot, just started asking questions.”

The couple relayed how Cohen had hit his head on his crib at 3 weeks old. Benton said the bleeding couldn’t have been caused by that, Lindsey said.

When she showed him pictures of Cohen’s bruised face and the bassinet, he said that didn’t “impress” him, she recalled.

Lindsey also told Benton about Cohen’s “traumatic” birth, but she said he told her the same — it didn’t impress him. During 17 hours of labor, both her and his heart rates dropped on several occasions, and she lost consciousness.

Cohen was born with the umbilical cord wrapped around his neck.

Benton declined to answer questions about Lindsey and her son’s case, even though she submitted a form to UMMC authorizing hospital employees to discuss her son’s medical records with Mississippi Today.

Lindsey attempted to get the recording of her conversations with Benton from the Children’s Safe Center, the medical center Benton oversees, but was unable to reach an employee, she said. Another mother who attempted to get similar recordings was told she must have an attorney to do so.

At UMMC, a surgeon drilled small openings called burr holes into Cohen’s skull to relieve pressure from the bleeding. He recovered and was discharged from UMMC.

The Tedfords appealed to a CPS case worker to allow Cohen to stay with Blake’s mother, who lived about 20 minutes from their home. CPS tentatively agreed, pending a successful home visit.

On Sept. 22, 2021, officials from Child Protective Services took the baby back to Tupelo. The hospital had diagnosed his injury as “nonaccidental trauma to child.”

For months, the Tedfords’ lives were divided between two houses. CPS had also removed their then-3-year-old daughter Cullen Claire from the home under a safety plan, and she was staying with Lindsey’s parents.

“She kept asking, ‘Why can’t I go home with my mommy and daddy? Is my brother ever going to get better?’ We couldn’t tell her, ‘You can’t come home because these people think we’re abusing you,’” said Lindsey.

Cohen wasn’t sleeping well away from his home, either, and his grandmother was in a state of constant exhaustion.

Over the next several months, CPS visited the Tedfords’ home, and the couple took (and passed) a polygraph test at the end of October, Lindsey said.

At a December safety plan review, Cullen Claire’s court-appointed guardian recommended returning her home because of the detrimental impact on her mental health — contingent on Lindsey receiving a mental evaluation because of the postpartum depression she revealed to Benton at the hospital in their conversation.

Several court dates for Cohen in early January passed with no action from CPS or the prosecution. They finally went back to court at the end of January.

“Our lawyer presented dismissal, saying there was basically not enough evidence to say these people abused their children,” recalled Lindsey. “He said, ‘This has been going on for five months now, nothing’s happened, we haven’t been to trial, and we just now got medical records. How long is this going to go on, and this family is broken?’”

When the judge asked the prosecution if they would be ready for trial in the next month, the attorneys said no.

Cohen’s court-appointed guardian also recommended the child return home. The judge ruled in the Tedfords’ favor, but stated Cohen should remain under a CPS safety plan involving periodic home visits. The plan ended March 2, 2022.

Life for the Tedfords is, on the outside, back to normal. But a lot has changed.

In addition to the health scare with Cohen and frequent trips to Memphis for his doctor appointments for ITP, his sister Cullen Claire, now 4, is struggling.

“We’re looking into child therapy for her. She tells us all the time that she doesn’t think we love her, that no one likes her. She’s struggled at school,” Lindsey said, starting to cry. “It’s definitely caused a lot of trauma.”

Lindsey has also been to therapy to work through what happened.

She said any time there’s a minor accident — bumps, falls and scrapes — she gets worried.

“What would it take for my kids to go back into CPS custody?” she wonders.

Lauren Ayers, Madison

After an afternoon at the playground on July 24, 2018, Lauren Ayers of Madison came home with her 10-week-old twins and almost 2-year-old son.

Ayers’ husband was in Oklahoma for work, so she was left alone with the three boys. She made spaghetti for her older son and herself. After they ate, she started the bedtime routine for the twins, Eli and Conner. She changed Conner’s diaper, swaddled him and laid him in his bassinet in her bedroom.

She put the other twin, Eli, on the plastic diaper changing pad on top of the dresser where she changes the boys’ diapers in their nursery. She had Eli’s onesie undone, so the lower half of his body was pressed directly against the uncovered pad.

The three children’s screams and cries created a cacophony in her home. Eli was kicking and thrashing on the changing pad.

Over the sound of the cries, she heard a clicking noise behind her and turned around, with Eli still on the changing table. Her older son sometimes liked to stand on the glider and rock back and forth, and she’d often have to intercept him before he fell. This time, though, he was playing with a retractable tape measure.

Turning back around, she was horrified to see Eli had scooted himself backwards and had fallen, landing on the crown of his head on the hard floor.

She remembers the resounding thud. When she ran over to pick him up, he was crying, but then became limp and lost consciousness.

“I thought he had broken his neck … I couldn’t find my phone, I was running outside and screaming for anybody to help me,” Ayers recalled. “I finally remembered where my phone was and ran in and called 911. He was unconscious, but he was breathing.”

Ayers’ neighborhood in Flora was new at the time, and she said she was either so upset she wasn’t being clear about where she lived or the emergency response officials weren’t sure where she was. She offered to meet them at Mannsdale Upper Elementary School, about a mile from her house.

“I loaded everybody up, got there … three different fire departments came,” she said. “I kept asking this off-duty firefighter … ‘What do we need to do?’ And he said, ‘Look, if anything’s wrong with him, you want him in the care of an ambulance.’”

With Ayers’ husband out of town and her family in Destin, her best friend came to the school along with her husband.

When no ambulance had arrived 30 minutes later, “the off-duty firefighter was like, ‘You’ve got to get him to a hospital,’” she said. “So my best friend’s husband drove us (to the University of Mississippi Medical Center).”

Ayers’ friend stayed with her and Eli, who had regained consciousness, when he arrived in the emergency room.Two of Ayers’ other friends were also in the emergency room with them, along with her in-laws.

“Thank God people could come back in the ER (because) they were witnesses of everything that happened … They tried to get an IV in him … They stuck him probably over 12 times,” Ayers described. “They couldn’t get blood from him.”

The nurses started a procedure called “milking,” said Ayers, where they would put both hands on Eli’s legs and arms and squeeze the skin in opposite directions in an attempt to get blood to flow.

They checked his stats, ran tests and admitted him to the pediatric intensive care unit for the night. A neurosurgeon reassured Ayers and her family that while the injury was bad, Eli would recover.

A scan the next morning showed Eli’s brain bleed had not gotten any larger, so he was moved to a regular room. That day, Ayers said the nurse told her the forensic pediatrician wanted to go over what happened. Ayers had no idea what a forensic pediatrician was.

Ayers attempted to get a recording of her conversation with Benton to share with Mississippi Today, but was told by the Children’s Safe Center, the medical center Benton oversees, that she would have to get an attorney to obtain it.

But she well remembers how the conversation began.

“He goes on to explain his (Eli’s) injuries and then asked if I remembered (the actress) Natasha Richardson. And I was like ‘Yea, yea, from the ‘Parent Trap’,’” she said. “And he goes, you know, ‘she had the skiing accident … This is the same injury your child has.’”

Richardson suffered a head injury and died two days later in 2009.

Ayers was shocked. She thought maybe Benton was about to tell her something was very wrong.

Benton abruptly closed his notebook and looked at her, she said.

“He said, ‘You’re under a lot of pressure right now. You have three kids, you were home alone — postpartum (depression) is a real thing,’” she remembered. “‘Tell me what really happened.”

Benton’s notes from Eli’s medical records show his certainty that the baby was not injured the way Ayers said.

“The fractures are discontinuous (do not connect) and appear to represent separate impact sites,” his notes show. “… Bilateral fractures are not reported in single fall incidents except where the skull fractures are continuous across sutures or in cases of bilateral out bending from a posterior impact causing symmetrical fractures.”

He goes on to note his concerns are whether Eli was developmentally able to kick or slide himself backwards and whether his skull fractures are “consistent” with Ayers’ account of what happened.

An occupational therapist who later evaluated Eli noted he was “quite active for age and may be slightly ahead with developmental milestones.” Ayers also took a video of Eli scooting himself backwards off a diaper changing pad, which she provided to Mississippi Today. In the video, he is wearing the same onesie outfit he was wearing in photos from the hospital.

She said Benton then told her he believes she threw the baby against a wall.

Yet the “most traumatizing part” of the first meeting with Benton, she said, was when he “strips that baby naked, and he’s looking, I guess, for signs of abuse.”

He started taking pictures of the bruises and needle marks from when Eli was admitted in the ER. Ayers asked what he was doing, and he said he believed she had inflicted the bruises.

He argued with her that the bruises were not from attempts to draw blood, and that “milking” was against hospital policy.

“I kept saying, ‘Don’t you see the needle marks?’ I was screaming at the nurses, ‘These are needle marks, you see them and you gave them to him!’” said Ayers.

Her friend had written down the names of the nurses who treated Eli in the emergency room, and Ayers begged Benton to talk to them. Ayers found a nurse who showed Benton records that when Eli first came to the hospital, no bruising or marks were noted.

A pediatric general surgeon who reviewed Eli two days later noted “bruising to left hand with visible venous access attempt noted” and “IV to right foot.”

Benton backed off, she said. But Ayers’ anxiety had only increased.

“At that point I was like, ‘They’re going to take this baby from me,’” she said.

Benton declined to answer questions about Ayers and her son’s case, even though Ayers submitted a form to UMMC authorizing hospital employees to discuss Eli’s medical records with Mississippi Today.

At the next meeting with Benton, Ayers had family members with her, including her father-in-law, a pharmacist. One of Eli’s tests had come back showing he had slightly elevated liver enzymes, which Benton believed indicated trauma to the abdomen.

Ayers’ father-in-law asked to review the test results.

“He (my father-in-law) literally looked at him and said, ‘Dr. Benton, with all due respect, these are stress-related elevated enzymes,’” she recalled. “‘These are not trauma-level numbers.’”

Benton said Eli would need to do a CT with contrast that requires fasting and radiation. Radiation exposure is particularly concerning in children because they are more sensitive to radiation. And because they have a longer life expectancy than adults, that results in a larger window of opportunity for them to experience radiation damage.

Ayers and her father-in-law objected to the CT, noting Ayers’ husband, Drew, had a kidney condition that made dehydration particularly dangerous, and there was a chance Eli might have the same issue.

But Benton insisted, and they relented.

In the paperwork under “clinical history” for the CT scan, it states: “Reported new bruising on the abdomen. Concern for blunt trauma to abdomen.” There had never been any mention of abdominal bruising in the medical records or to Ayers up until that point, and the CT was performed two days after Eli came to the hospital.

The scan came back normal.

“No evidence of blunt trauma to the abdomen. No acute fractures or dislocations,” the report stated.

Eli was discharged but subjected to another full body X-ray several weeks after he left, according to records. A case worker from Child Protective Services visited Ayers’ home and cleared Eli to return. Several weeks later, a Madison County sheriff’s investigator also interviewed Ayers.

The case was closed that day, the incident report stated.

What haunts Ayers even four years later is wondering what happens to mothers without the resources she had: the ability to hire an attorney, a family member in the medical field to sit in on meetings with Benton and the support of friends and family who were in the emergency room and hospital with her.

“This man should have some more oversight … if you’re going to subject a 10-week-old to all these tests, two MRIs, a CT, X-rays, you should have your evidence in order,” said Ayers, who said she struggled “with some pretty dark days” after the accusations from Benton and the experience in the hospital.

Ayers filed a complaint with the Mississippi State Board of Medical Licensure in March of last year. In her complaint, she highlighted the unexplained “new bruising to abdomen” on the notes for his CT – bruising that was never mentioned anywhere else in his medical records.

“I would say, about 10 doctors signed off that my child (the patient) had ZERO bruising anywhere on his body upon admittance to the hospital … Scott Benton couldn’t ethically order this CT with contrast on my child bc (because) his liver enzymes weren’t actually elevated enough to need it,” she wrote. “ … Before I take matters further, I’d really like someone to call me, asap.”

She never heard anything back.

Editor’s note: Kate Royals, Mississippi Today’s community health editor since January 2022, worked as a writer/editor for UMMC’s Office of Communications from November 2018 through August 2020, writing press releases and features about the medical center’s schools of dentistry and nursing.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=210275

Mississippi Today

Hospitals see danger in Medicaid spending cuts

Mississippi hospitals could lose up to $1 billion over the next decade under the sweeping, multitrillion-dollar tax and policy bill President Donald Trump signed into law last week, according to leaders at the Mississippi Hospital Association.

The leaders say the cuts could force some already-struggling rural hospitals to reduce services or close their doors.

The law includes the largest reduction in federal health and social safety net programs in history. It passed 218-214, with all Democrats voting against the measure and all but five Republicans voting for it.

In the short term, these cuts will make health care less accessible to poor Mississippians by making the eligibility requirements for Medicaid insurance stiffer, likely increasing people’s medical debt.

In the long run, the cuts could lead to worsening chronic health conditions such as diabetes and obesity for which Mississippi already leads the nation, and making private insurance more expensive for many people, experts say.

“We’ve got about a billion dollars that are potentially hanging in the balance over the next 10 years,” Mississippi Hospital Association President Richard Roberson said Wednesday during a panel discussion at his organization’s headquarters.

“If folks were being honest, the entire system depends on those rural hospitals,” he said.

Mississippi’s uninsured population could increase by 160,000 people as a combined result of the new law and the expiration of Biden-era enhanced subsidies that made marketplace insurance affordable – and which Trump is not expected to renew – according to KFF, a health policy research group.

That could make things even worse for those who are left on the marketplace plans.

“Younger, healthier people are going to leave the risk pool, and that’s going to mean it’s more expensive to insure the patients that remain,” said Lucy Dagneau, senior director of state and local campaigns at the American Cancer Society.

Among the biggest changes facing Medicaid-eligible patients are stiffer eligibility requirements, including proof of work. The new law requires able-bodied adults ages 19 to 64 to work, do community service or attend an educational program at least 80 hours a month to qualify for, or keep, Medicaid coverage and federal food aid.

Opponents say qualified recipients could be stripped of benefits if they lose a job or fail to complete paperwork attesting to their time commitment.

Georgia became the case study for work requirements with a program called Pathways to Coverage, which was touted as a conservative alternative to Medicaid expansion.

Ironically, the 54-year-old mechanic chosen by Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp to be the face of the program got so fed up with the work requirements he went from praising the program on television to saying “I’m done with it” after his benefits were allegedly cancelled twice due to red tape.

Roberson sent several letters to Mississippi’s congressional members in weeks leading up to the final vote on the sweeping federal legislation, sounding the alarm on what it would mean for hospitals and patients.

Among Roberson’s chief concerns is a change in the mechanism called state directed payments, which allows states to beef up Medicaid reimbursement rates – typically the lowest among insurance payors. The new law will reduce those enhanced rates to nearly as low as the Medicare rate, costing the state at least $500 million and putting rural hospitals in a bind, Roberson told Mississippi Today.

That change will happen over 10 years starting in 2028. That, in conjunction with the new law’s one-time payment program called the Rural Health Care Fund, means if the next few years look normal, it doesn’t mean Mississippi is safe, stakeholders warn.

“We’re going to have a sort of deceiving situation in Mississippi where we look a little flush with cash with the rural fund and the state directed payments in 2027 and 2028, and then all of a sudden our state directed payments start going down and that fund ends and then we’re going to start dipping,” said Leah Rupp Smith, vice president for policy and advocacy at the Mississippi Hospital Association.

Even with that buffer time, immediate changes are on the horizon for health care in Mississippi because of fear and uncertainty around ever-changing rules.

“Hospitals can’t budget when we have these one-off programs that start and stop and the rules change – and there’s a cost to administering a program like this,” Smith said.

Since hospitals are major employers – and they also provide a sense of safety for incoming businesses – their closure, especially in rural areas, affects not just patients but local economies and communities.

U.S. Rep. Bennie Thompson is the only Democrat in Mississippi’s congressional delegation. He voted against the bill, while the state’s two Republican senators and three Republican House members voted for it. Thompson said in a statement that the new law does not bode well for the Delta, one of the poorest regions in the U.S.

“For my district, this means closed hospitals, nursing homes, families struggling to afford groceries, and educational opportunities deferred,” Thompson said. “Republicans’ priorities are very simple: tax cuts for (the) wealthy and nothing for the people who make this country work.”

While still colloquially referred to as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, the name was changed by Democrats invoking a maneuver that has been used by lawmakers in both chambers to oppose a bill on principle.

“Democrats are forcing Republicans to delete their farcical bill name,” Senate Democratic Leader Charles Schumer of New York said in a statement. “Nothing about this bill is beautiful — it’s a betrayal to American families and it’s undeserving of such a stupid name.”

The law is expected to add at least $3.3 trillion to the nation’s debt over the next 10 years, according to the most recent estimate from the Congressional Budget Office.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Hospitals see danger in Medicaid spending cuts appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article reports on the negative impacts of a major federal tax and policy bill on Medicaid funding and rural hospitals in Mississippi. While it presents factual details and statements from stakeholders, the tone and framing emphasize the harmful consequences for vulnerable populations and health care access, aligning with concerns typically raised by center-left perspectives. The article highlights opposition by Democrats and critiques the bill’s priorities, particularly its effect on poor and rural communities, suggesting sympathy toward social safety net preservation. However, it maintains mostly factual reporting without overt partisan language, resulting in a moderate center-left bias.

Crooked Letter Sports Podcast

Podcast: The Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame Class of ’25

The MSHOF will induct eight new members on Aug 2. Rick Cleveland has covered them all and he and son Tyler talk about what makes them all special.

Stream all episodes here.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Podcast: The Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame Class of '25 appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Mississippi Today

‘You’re not going to be able to do that anymore’: Jackson police chief visits food kitchen to discuss new public sleeping, panhandling laws

Diners turned watchful eyes to the stage as Jackson Police Chief Joseph Wade took to the podium. He visited Stewpot Community Services during its daily free lunch hour Thursday to discuss new state laws, which took effect two days earlier, targeting Mississippians experiencing homelessness.

“I understand that you are going through some hard times right now. That’s why I’m here,” Wade said to the crowd. “I felt it was important to come out here and speak with you directly.”

Wade laid out the three bills that passed earlier this year: House Bill 1197, the “Safe Solicitation Act,” HB 1200, the “Real Property Owners Protection Act” and HB 1203, a bill that prohibits camping on public property.

“Sleeping and laying in public places, you’re not going to be able to do that anymore,” he said. “There’s a law that has been passed that you can’t just set up encampments on public or private properties where it’s a public nuisance, it’s a problem.”

The “Real Property Owners Protection Act,” authored by Rep. Brent Powell, R-Brandon, is a bill that expedites the process of removing squatters. The “Safe Solicitation Act,” authored by Rep. Shanda Yates, I-Jackson, requires a permit for panhandling and allows people to be charged with a misdemeanor if they violate this law. The offense is punishable by a fine not to exceed $300 and an offender could face up to six months in jail. Wade said he’s currently working with his legal department to determine the best strategy for creating and issuing permits.

“We’re going to navigate these legal challenges, get some interpretations, not only from our legal department, but the Attorney General’s office to ensure that we are doing it legally and lawfully, because I understand that these are citizens,” he said. “I understand that they deserve to be treated with respect, and I understand that we are going to do this without violating their constitutional rights.”

Wade said the Jackson Police Department is steadily fielding reports of squatters in abandoned properties and the law change gives officers new power to remove them more quickly. The added challenge? Figuring out what to do with a person’s belongings.

“These people are carrying around what they own, but we are not a repository for all of their stuff,” he said. “So, when we make that arrest, we’ve got to have a strategic plan as to what we do with their stuff.”

Wade said there needs to be a deeper conversation around the issues that lead someone to becoming homeless.

“A lot of people that we’re running across that are homeless are also suffering from medical conditions, mental health issues, and they’re also suffering from drug addiction and substance abuse. We’ve got to have a strategic approach, but we also can’t log jam our jail down in Raymond,” Wade said.

He estimates that more than 800 people are currently incarcerated at the Raymond Detention Center, and any increase could strain the system as the laws continue to be enforced.

“I think there’s layers that we have to work through, there’s hurdles that we are going to overcome, but we’ve got to make sure that we do it and make sure that my team and JPD is consistent in how we enforce these laws,” Wade said.

Diners applauded Wade after he spoke, in between bites of fried chicken, salad, corn and 4th of July-themed packaged cakes. Wade offered to answer questions, but no one asked any.

Rev. Jill Buckley, executive director of Stewpot, said that the legislation is a good tool to address issues around homelessness and community needs. She doesn’t want to see people who are homeless be criminalized, but she also wants communities to be safe.

“I support people’s right to self determine, and we can’t impose our choices on other people, but there are some cases in which that impinges on community safety, and so to the extent that anyone who is camping or panhandling or squatting and is a danger to themselves and others, of course, I fully support that kind of law. I don’t support homelessness being criminalized as such,” Buckley said.

Many of the people Wade addressed while they ate Thursday said they have housing, don’t panhandle, and shouldn’t be directly impacted by the legislation. But Marcus Willis, 42, said it would make more sense if elected officials wanted to combat the negative impacts of homelessness that they help more people secure employment.

“There ain’t enough jobs,” said Willis, who was having lunch with his girlfriend Amber Ivy.

The two live in an apartment together nearby on Capitol Street, where Ivy landed after her mother, whom Ivy had been living with, suffered a stroke and lost the property. Similarly, Willis started coming to eat at Stewpot after his grandmother, whose house he used to visit for lunch, passed away.

Willis holds odd jobs – cutting grass, home and auto repair – so the income is inconsistent, and every opportunity for stable employment he said he’s found is outside of Jackson in the suburbs. The couple doesn’t have a car.

Making rent every month usually depends on their ability to find someone to help chip in, said Ivy, who is in recovery from substance abuse. She said she’s watched problems surrounding homelessness grow over the years in Jackson. Ivy grew up near Stewpot and has lived in various neighborhoods across the city – except for the times she moved out of state when things got too rough.

“There was just moments where I just had to leave,” Ivy said. “Sometimes if you hit a slump here, there’s almost no way for you to get out of it.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post 'You're not going to be able to do that anymore': Jackson police chief visits food kitchen to discuss new public sleeping, panhandling laws appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Right

This article primarily reports on new laws in Jackson, Mississippi, targeting public sleeping, panhandling, and squatting, focusing on statements by Police Chief Joseph Wade and community perspectives. The coverage presents the legislative measures—authored by Republican and independent lawmakers—with a tone that emphasizes law enforcement challenges and community safety, reflecting a conservative approach to homelessness as a public order issue. While it includes voices concerned about criminalization and the need for social support, the overall framing centers on law enforcement and property protection. The article maintains factual reporting without overt editorializing but leans slightly toward a center-right perspective by highlighting legal enforcement as a solution.

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days ago

Real-life Uncle Sam's descendants live in Arkansas

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed5 days ago

'Big Beautiful Bill' already felt at Georgia state parks | FOX 5 News

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed6 days ago

LOFT report uncovers what led to multi-million dollar budget shortfall

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago

Alabama schools to lose $68 million in federal grants under Trump freeze

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days ago

Celebrate St. Louis returns with new Superman-themed drone show

-

News from the South - South Carolina News Feed7 days ago

South Carolina lawmakers react as House approves Trump’s sweeping economic package

-

Local News6 days ago

Maroon Tide football duo commits to two different SEC Teams!

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed5 days ago

Raleigh caps Independence Day with fireworks show outside Lenovo Center