Construction underway at China’s Lingdingyang Bridge.

Ari Perez, Quinnipiac University

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

How do they build things like tunnels and bridges underwater? – Helen, age 10, Somerville, Massachusetts

When I was a kid, I discovered a Calvin and Hobbes comic strip that posed one of my own burning questions: How do they know the load limit on bridges? Calvin’s dad (incorrectly) tells him, “They drive bigger and bigger trucks over it until it breaks. Then they weigh the last truck and rebuild the bridge.”

Several decades later, I’m a geotechnical engineer. That means that I work on any construction projects that involve soil. Now I know the real answers to things people wonder about infrastructure. Oftentimes, like Calvin’s dad, they’re thinking about things from the wrong direction. Engineers don’t typically determine the load limit on a bridge; instead, they build the bridge to carry the load they’re expecting.

It’s the same with another question I hear from time to time: How do engineers build things underwater? They actually don’t typically build things underwater – instead they build things that then end up underwater. Here’s what I mean.

Building underground, beneath the water

Sometimes when you’re building underwater, you’re really building underground. It’s not about the water you see at the surface but rather what surrounds the actual structure you’re building.

If there’s rock or soil all around what you’re constructing, that’s typically thought of as underground construction – even if there’s a layer of water above it and that’s all you see from above.

Underground construction usually uses powerful tunnel-boring machines to excavate soil directly. This machine is often called a mole for a reason. Like the animal, it creates a tunnel similar to a burrow by excavating horizontally through the ground, removing the excavated material out behind it. Done with care, this method can successfully build a tunnel through the ground beneath a body of water that can then be lined and reinforced.

Engineers used this method to build the Chunnel, for instance, a railway tunnel beneath the English Channel that connects England and France.

Construction crew with a tunneling shield that allowed them to build the Sumner Tunnel in Boston, Mass., in the 1930s.

While modern machinery is quite advanced, this method of construction started about 200 years ago with the tunneling shield. Initially, these were temporary support structures that provided a safe space from which workers could excavate. New temporary structures were built deeper and deeper as the tunnel grew. As the designs improved with experience, the shields were built to be mobile and eventually evolved into the modern tunnel-boring machine.

Building on dry land before moving into place

Some structures will ultimately be surrounded by water, resting on a riverbed or ocean floor. Luckily, engineers have some tricks up their sleeves to build bridges and tunnels that have components in direct contact with the water.

Underground construction is dangerous and hard to access. Dealing with water brings additional challenges. While soil and rock can be moved aside to create a stable opening, water will always move in to fill any gap and must continuously be pumped away.

Human beings, materials and machinery don’t really work well underwater, either. People need a constant air supply. Placing concrete is difficult underwater, and some materials work only on dry land. And since gas engines rely on air to operate, underwater equipment is very limited.

Some smaller tasks – aligning and joining pre-built sections of tunnel or inspecting to make sure submersion didn’t damage anything – are performed beneath the waves, but the bulk of construction is unlikely to be. Once the structure is in place, there’s constant monitoring and assessment happening underwater.

Because people generally can’t build underwater, there are two options: Do the building in the open and move it underwater, or temporarily transform the underwater site into a dry one.

For the first option, crews typically build parts of the structure on dry land and then sink them into place. For instance, the Ted Williams Tunnel in Boston was constructed in sections in a shipyard. Workers dredged the tunnel’s future path in Boston Harbor, cleaning mud and other refuse out of the way. Then they placed the sealed segments along the prepared trench. Once the segments were connected, they opened the ends of the segments to create one long, continuous tube. Finally, the tunnel was covered with soil and rock. Very little of the construction process was actually done underwater.

In other cases, such as in shallow water, construction workers may be able to build directly from the surface. For instance, workers can drive waterfront retaining walls made out of sheet metal into the soil directly from a barge, without having to divert the water.

Temporarily clearing the water away

The second option is to get rid of the underwater problem entirely.

While creating a dry site at the bottom of a body of water is difficult, it does have a long history. After leading the sack of Rome in 410 C.E., Visigoth king Alaric died on his way home. In order to protect his magnificent burial from grave robbers, Alaric’s people temporarily diverted a local river to bury him and his loot in the riverbed before letting the river rush back over.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers used a cofferdam to hold back the water during construction of the Olmsted Locks and Dam on the Ohio River.

Nowadays, a project like this would use a cofferdam: a temporary, watertight enclosure that can be pumped dry to provide an open and safe site for construction. Once the area is enclosed and pumped free of water, you’re in the realm of regular construction.

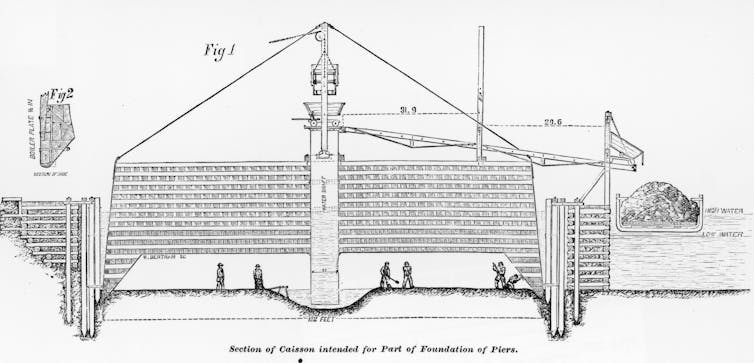

Using a caisson is another way to provide a dry area at a site that is typically underwater. A caisson is typically a prefabricated and water-tight structure, shaped like an upside-down cup, that a crew sinks into the water. They keep it pressurized to ensure that water will not rush in. Once the caisson is on the floor of the body of water, the air pressure and pumping keep the site dry and allow construction workers to build inside. The caisson becomes part of the finished structure.

Workers built parts of the Brooklyn Bridge using caissons that provided a bubble of dryness and breathable air on the riverbed.

Builders constructed the piers of the Brooklyn Bridge using caissons. Although the caissons were structurally safe, the difference in pressure affected many workers, including the chief engineer, Washington Roebling. He developed caisson disease – more commonly known as decompression sickness – and had to resign.

Underwater construction is a complex and difficult task, but engineers have developed several ways to build underwater … often by not building underwater at all.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

Ari Perez, Associate Professor of Civil Engineering, Quinnipiac University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.