Casey Harrell, who has ALS, works with a brain-computer interface to turn his thoughts into words. Nicholas Card

Nicholas Card, University of California, Davis

Brain-computer interfaces are a groundbreaking technology that can help paralyzed people regain functions they’ve lost, like moving a hand. These devices record signals from the brain and decipher the user’s intended action, bypassing damaged or degraded nerves that would normally transmit those brain signals to control muscles.

Since 2006, demonstrations of brain-computer interfaces in humans have primarily focused on restoring arm and hand movements by enabling people to control computer cursors or robotic arms. Recently, researchers have begun developing speech brain-computer interfaces to restore communication for people who cannot speak.

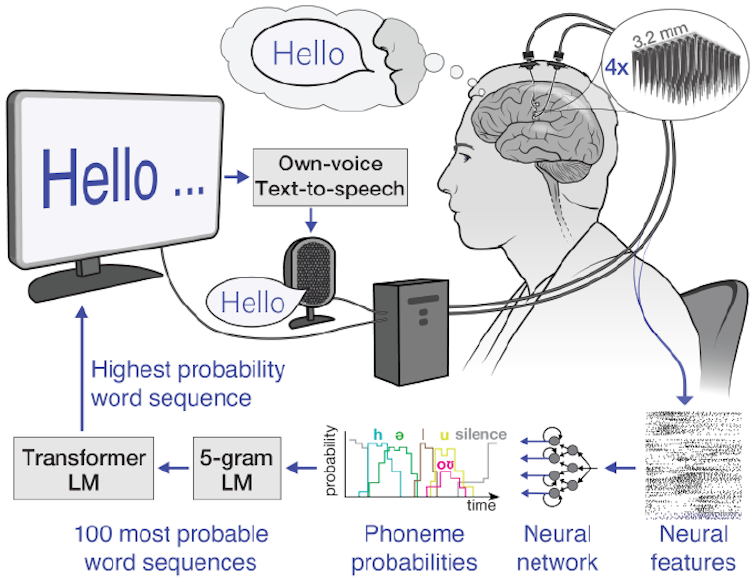

As the user attempts to talk, these brain-computer interfaces record the person’s unique brain signals associated with attempted muscle movements for speaking and then translate them into words. These words can then be displayed as text on a screen or spoken aloud using text-to-speech software.

I’m a reseacher in the Neuroprosthetics Lab at the University of California, Davis, which is part of the BrainGate2 clinical trial. My colleagues and I recently demonstrated a speech brain-computer interface that deciphers the attempted speech of a man with ALS, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. The interface converts neural signals into text with over 97% accuracy. Key to our system is a set of artificial intelligence language models – artificial neural networks that help interpret natural ones.

Recording brain signals

The first step in our speech brain-computer interface is recording brain signals. There are several sources of brain signals, some of which require surgery to record. Surgically implanted recording devices can capture high-quality brain signals because they are placed closer to neurons, resulting in stronger signals with less interference. These neural recording devices include grids of electrodes placed on the brain’s surface or electrodes implanted directly into brain tissue.

In our study, we used electrode arrays surgically placed in the speech motor cortex, the part of the brain that controls muscles related to speech, of the participant, Casey Harrell. We recorded neural activity from 256 electrodes as Harrell attempted to speak.

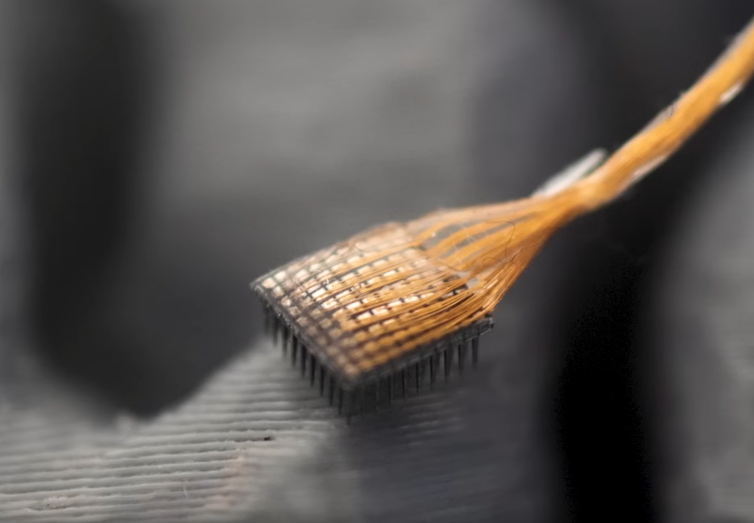

An array of 64 electrodes that embed into brain tissue records neural signals. UC Davis Health

Decoding brain signals

The next challenge is relating the complex brain signals to the words the user is trying to say.

One approach is to map neural activity patterns directly to spoken words. This method requires recording brain signals corresponding to each word multiple times to identify the average relationship between neural activity and specific words. While this strategy works well for small vocabularies, as demonstrated in a 2021 study with a 50-word vocabulary, it becomes impractical for larger ones. Imagine asking the brain-computer interface user to try to say every word in the dictionary multiple times – it could take months, and it still wouldn’t work for new words.

Instead, we use an alternative strategy: mapping brain signals to phonemes, the basic units of sound that make up words. In English, there are 39 phonemes, including ch, er, oo, pl and sh, that can be combined to form any word. We can measure the neural activity associated with every phoneme multiple times just by asking the participant to read a few sentences aloud. By accurately mapping neural activity to phonemes, we can assemble them into any English word, even ones the system wasn’t explicitly trained with.

To map brain signals to phonemes, we use advanced machine learning models. These models are particularly well-suited for this task due to their ability to find patterns in large amounts of complex data that would be impossible for humans to discern. Think of these models as super-smart listeners that can pick out important information from noisy brain signals, much like you might focus on a conversation in a crowded room. Using these models, we were able to decipher phoneme sequences during attempted speech with over 90% accuracy.

From phonemes to words

Once we have the deciphered phoneme sequences, we need to convert them into words and sentences. This is challenging, especially if the deciphered phoneme sequence isn’t perfectly accurate. To solve this puzzle, we use two complementary types of machine learning language models.

The first is n-gram language models, which predict which word is most likely to follow a set of n words. We trained a 5-gram, or five-word, language model on millions of sentences to predict the likelihood of a word based on the previous four words, capturing local context and common phrases. For example, after “I am very good,” it might suggest “today” as more likely than “potato”. Using this model, we convert our phoneme sequences into the 100 most likely word sequences, each with an associated probability.

The second is large language models, which power AI chatbots and also predict which words most likely follow others. We use large language models to refine our choices. These models, trained on vast amounts of diverse text, have a broader understanding of language structure and meaning. They help us determine which of our 100 candidate sentences makes the most sense in a wider context.

By carefully balancing probabilities from the n-gram model, the large language model and our initial phoneme predictions, we can make a highly educated guess about what the brain-computer interface user is trying to say. This multistep process allows us to handle the uncertainties in phoneme decoding and produce coherent, contextually appropriate sentences.

How the UC Davis speech brain-computer interface deciphers neural activity and turns them into words. UC Davis Health

Real-world benefits

In practice, this speech decoding strategy has been remarkably successful. We’ve enabled Casey Harrell, a man with ALS, to “speak” with over 97% accuracy using just his thoughts. This breakthrough allows him to easily converse with his family and friends for the first time in years, all in the comfort of his own home.

Speech brain-computer interfaces represent a significant step forward in restoring communication. As we continue to refine these devices, they hold the promise of giving a voice to those who have lost the ability to speak, reconnecting them with their loved ones and the world around them.

However, challenges remain, such as making the technology more accessible, portable and durable over years of use. Despite these hurdles, speech brain-computer interfaces are a powerful example of how science and technology can come together to solve complex problems and dramatically improve people’s lives.

Nicholas Card, Postdoctoral Fellow of Neuroscience and Neuroengineering, University of California, Davis

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.