Mississippi Today

How a ‘Goon Squad’ of Deputies Got Away With Years of Brutality

Brian Howey and Nate Rosenfield investigated dozens of arrests made by Rankin County deputies to report this article, which is part of a series by The Times’s Local Investigations Fellowship examining the power of sheriffs’ offices in Mississippi.

For nearly two decades, a loose band of sheriff’s deputies roamed impoverished neighborhoods across a central Mississippi county, meting out their own version of justice.

Narcotics detectives and patrol officers, some who called themselves the Goon Squad, barged into homes in the middle of the night, accusing people inside of dealing drugs. Then they handcuffed or held them at gunpoint and tortured them into confessing or providing information, according to dozens of people who say they endured or witnessed the assaults.

They described violence that sometimes went on for hours and seemed intended to strike terror into the deputies’ targets.

In the pursuit of drug arrests, deputies of the Rankin County Sheriff’s Department shocked Robert Jones with a Taser in 2018 while he lay submerged in a flooded ditch, then rammed a stick down his throat until he vomited blood, he said.

During a raid the same year, deputies choked Mitchell Hobson with a lamp cord and waterboarded him to simulate drowning, he said, then beat him until the walls were spattered with his blood. That raid took place at the home of Rick Loveday, a sheriff’s deputy in a neighboring county, who said he was dragged half-naked from his bed at gunpoint, before deputies jabbed a flashlight threateningly at his buttocks and then pummeled him relentlessly.

The string of violence might have continued unchecked if not for one near-fatal raid in January.

According to a Justice Department investigation, deputies broke into the home of two Black men, Michael Jenkins and Eddie Parker, shocked them with Tasers and threatened to rape them. Deputy Hunter Elward shoved the barrel of a gun into Mr. Jenkins’s mouth, not realizing a bullet was in the chamber, and pulled the trigger. Mr. Jenkins was grievously injured, the incident was thrust into the national spotlight, and in August five deputies and a police officer pleaded guilty to criminal charges.

Rankin County Sheriff Bryan Bailey said in a press conference this summer that he was stunned to learn of the “horrendous crimes” committed by his deputies. “Never in my life did I think it would happen in this department.”

But an investigation by The New York Times and the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting at Mississippi Today reveals a history of blatant and brutal incidents stretching back to at least 2004.

Reporters examined hundreds of pages of court records and sheriff’s office reports and interviewed more than 50 people who say they witnessed or experienced torture at the hands of the Rankin County Sheriff’s Department. What emerged was a pattern of violence that was neither confined to a small group of deputies nor hidden from department leaders.

Many of those who said they experienced violence filed lawsuits or formal complaints, detailing their encounters with the department. A few said they had contacted Sheriff Bailey directly, only to be ignored.

The Times and Mississippi Today identified 20 deputies who were present at one or more of the incidents — many assigned to narcotics or the night-shift patrol — who were present at one or more incidents.

Christian Dedmon, Rankin’s former narcotics detective, was involved in eight incidents, department records show. Also present for at least one arrest: former Undersheriff Paul Holley and former Deputy Dean Scott, who is now police chief in Pearl, Miss.

Brett McAlpin, former chief investigator for the department, was involved in at least 13 of the arrests and was repeatedly described by witnesses as leading the raids. He was named in at least four lawsuits and six complaints going back to 2010. Even so, Sheriff Bailey named him investigator of the year in 2013. This year, he pleaded guilty to criminal charges for his role in the January raid.

Taken together, the reporting shows how Rankin deputies were allowed to operate with impunity, while racking up arrests for relatively minor drug infractions and leaving entire neighborhoods in fear of violent raids.

Among the dozens of allegations reviewed, The Times and Mississippi Today were able to corroborate 17 incidents involving 22 victims based on witness interviews, medical records, photographs of injuries and other documents.

In nearly half the cases, Taser logs obtained from the department through a public records request helped corroborate the allegations. Electronically recorded dates and times of Taser triggers lined up with witness accounts and suggested that deputies repeatedly shocked people for longer than is considered safe.

The Taser logs also suggest that the scope of the violence may extend much farther.

At least 32 times over the past decade, Rankin deputies fired their Tasers more than five times in under an hour, activating them for at least 30 seconds in total — double the recommended limit. Experts in Taser use who reviewed the logs called these incidents highly suspicious.

“This is not typical Taser use,” said Seth Stoughton, faculty director of the Excellence in Policing & Public Safety program at the University of South Carolina. “There’s just no justification for that.”

It is impossible to tell from the logs alone whether a series of shocks were aimed at one target, and whether they all made contact. Incident reports by the deputies offer little clarity, because in nearly every case they failed to mention that a Taser was used at all.

Over the past year, The Times and Mississippi Today have investigated how powerful sheriffs in rural Mississippi have dodged accountability in the face of misconduct allegations. The reporting exposed numerous sexual abuse accusations against two sheriffs in counties near Rankin, along with evidence that Sheriff Bailey obtained subpoenas to surveil his girlfriend’s phone calls.

Sheriff Bailey has faced increased scrutiny since the Justice Department began to investigate his deputies’ conduct this year, and the NAACP and local activist groups have called for his resignation. After 12 years as sheriff, he was re-elected in November when he ran unopposed.

The deputies accused of being involved in violent arrests declined to comment or did not respond to repeated requests for interviews.

It is not always clear what actions individual deputies took during the incidents. Witnesses often did not know their names and many of the deputies did not wear uniforms or name tags during the raids.

Jason Dare, a lawyer for the department, declined to comment on The Times and Mississippi Today’s findings.

During a brief phone interview on Sunday, Sheriff Bailey repeatedly declined to comment. Told that several high-ranking deputies were involved in arrests that had sparked accusations of brutal treatment, he said, “I have 240 employees, there’s no way I can be with them each and every day.”

On Tuesday, the department announced that it had updated its internal policies and that deputies would receive training on federal civil rights laws.

A statement from the department that referred to the January assault without acknowledging a broader pattern said, “Even though the prior actions were abnormal and extreme, we will make every effort to ensure that they do not occur in the future.”

New Problems, Old Tactics

For most of its history, Rankin County was a rural area dominated by farmland and forests.

That began to change when white flight reached the capital city of Jackson in the 1960s and Rankin’s fields gave way to subdivisions and strip malls.

But tucked among the stately homes and manicured lawns, some of the county’s most impoverished residents live in run-down trailers and makeshift shacks, a few without running water or electricity.

These neighborhoods were hit hard in the early 2000s as meth — cheap, highly addictive and easy to manufacture in isolated places — spread across rural America like wildfire.

Local sheriffs, even in small departments, set up special narcotics units and joined state and federal task forces in the War on Drugs. The Rankin County Sheriff’s Department responded by targeting low-income communities and policing them relentlessly.

In an area called Robinhood, residents said home raids became routine and it felt as if they couldn’t go to the corner store without being stopped and searched.

“Once they start picking on you,” said a former resident, Matasha Harris, “they will not leave you alone.”

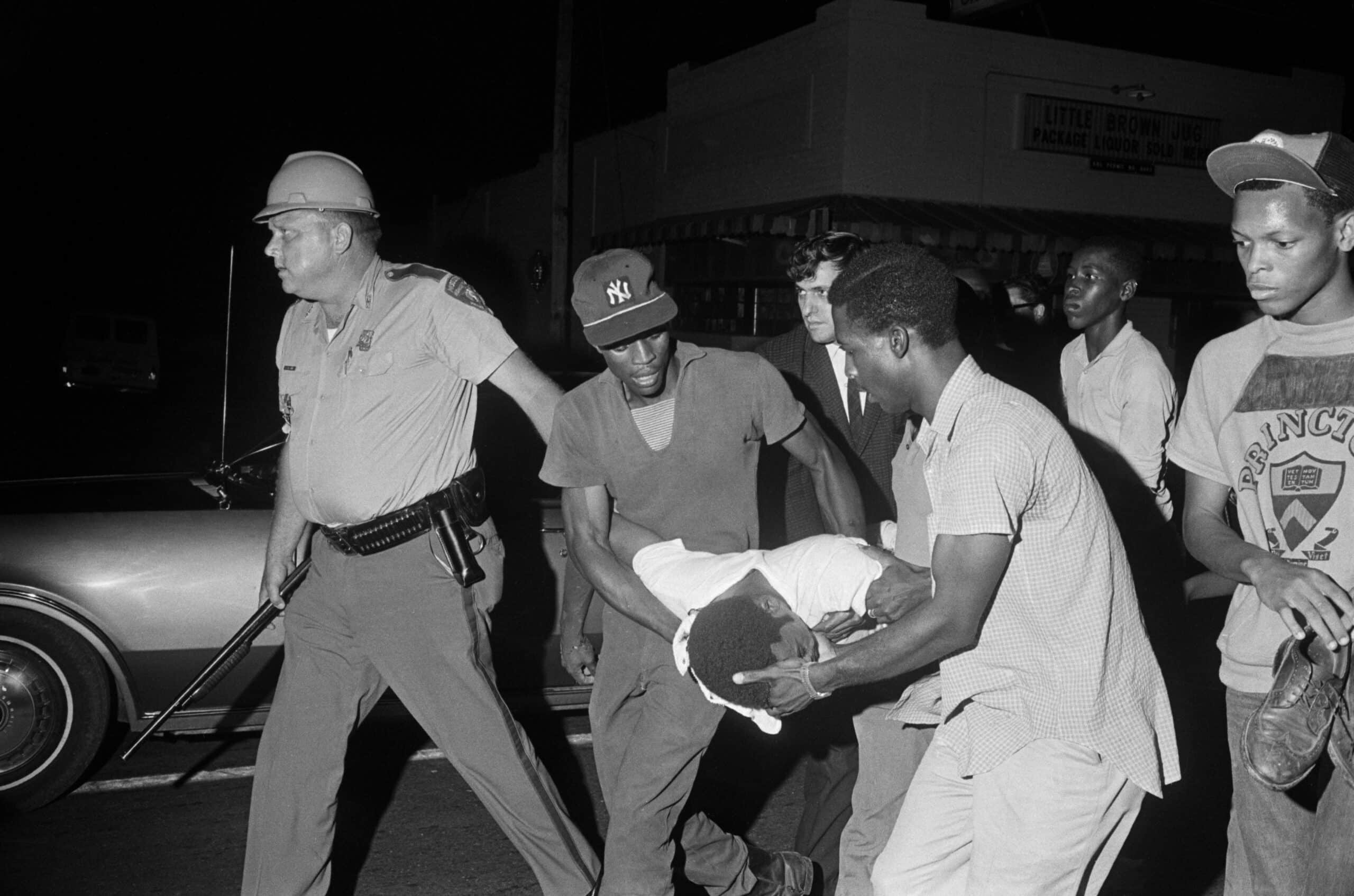

Though Rankin deputies appear to have targeted people based on suspected drug use, not race — most of their accusers were white — their tactics could have been pulled from the Jim Crow era, when sheriffs and their deputies harassed and beat Black Southerners and civil rights activists.

During that period, deputies coerced false confessions, sometimes using cattle prods or “the water cure”: pouring water into suspects’ nostrils until they complied.

Priscilla Perkins, co-president of the John & Vera Mae Perkins Foundation, a nonprofit based in Jackson, Miss., that promotes racial reconciliation, said the Goon Squad’s acts reminded her of the reign of terror against civil rights activists that often involved law enforcement officers.

“It’s the hidden shame of Mississippi and America,” she said. “People are still trying to cover it up.”

Among the officers of that era accused of beating Black residents was Lloyd Jones, a state trooper who would become sheriff in nearby Simpson County.

A Justice Department investigation long after his death found that he had bragged to a colleague about fatally shooting a Black man, Benjamin Brown, in the back during a 1967 standoff between police officers and civil rights protesters.

In 1970, Mr. Jones participated in the beating of the Rev. John Perkins in the Rankin County jail, which culminated with a deputy jabbing a fork up his nose, according to the pastor and witnesses who testified against the officers.

As sheriff, he gave Bryan Bailey his first job in law enforcement.

“He is on my life’s wall of gratitude and had a huge impact on who I am,” Sheriff Bailey wrote on Facebook in 2015. “Not a day goes by that I don’t think about him or recall something that he taught me.”

Sheriff Bailey called him a mentor. But years before, Simpson County residents had begun calling him something else: “Goon” Jones.

Scope of Abuse

It’s unclear when Rankin County deputies adopted their nickname, but last year, they ordered commemorative coins emblazoned with cartoonish gangsters and the words “Lt. Middleton’s Goon Squad.” Lt. Jeffrey Middleton was the squad’s supervisor. He is among the five deputies who pleaded guilty to criminal charges stemming from the January raid on Mr. Parker and Mr. Jenkins.

A Justice Department investigation this year found that Rankin County deputies chose the name Goon Squad “because of their willingness to use excessive force and not report it.”

The investigation found that Mr. McAlpin, along with a narcotics detective, Christian Dedmon, and Goon Squad members burst into Mr. Parker’s home, tortured and humiliated the men while demanding to know where drugs were, and then disposed of the evidence.

Across the 17 cases for which reporters found corroborating witnesses and evidence, accusers described similar tactics by deputies, almost always over small drug busts.

Deputies held people down while punching and kicking them or shocked them repeatedly with Tasers. They shoved gun barrels into people’s mouths. Three people said deputies had waterboarded them until they thought they would suffocate. Five said deputies had told them to move out of the county.

Many of the targets teetered on the edge of homelessness and were caught with a few grams of meth or with only drug paraphernalia — a glass pipe or used syringe. Several people sat in jail for days or weeks only to have their charges dropped.

The largest bust among the incidents examined was for a $420 heroin sale.

In 2018, a confidential informant arranged an $80 meth deal at Jerry Manning’s home. Mr. Manning, who denies being part of the sale, said he heard deputies burst into his trailer and scream his name.

When he went to investigate, deputies pinned him to the floor. They said they wanted to test their new Tasers on him to see which hurt more, he said.

“They got me in my private parts, they got me in my head,” Mr. Manning said. “They kept tasing and tasing and tasing.”

Taser logs indicate that two of the nine deputies involved that night, James Rayborn and Cody Grogan, together triggered their Tasers at least 15 times during the two-and-a-half-hour raid.

As the deputies ransacked his home looking for drugs, Mr. Manning said, they wrapped a pair of jeans around his head and punched him repeatedly in the face before using a blowtorch to melt a metal nutcracker handle onto his bare leg as he screamed. On Mr. McAlpin’s orders, Mr. Manning said, a deputy then forced him to sit, pulled a belt around his neck and yanked it upward, choking him until he believed he would suffocate.

Three other men in the trailer that night described violent attacks. Garry Curro, a 64-year-old Air Force veteran, said deputies handcuffed, beat and shocked him. Adam Porter says Mr. McAlpin threw him into a glass mirror, then took Mr. Porter’s pocketknife and sliced his pants to ribbons, demanding to know where the drugs were. Mr. Manning’s roommate, James Lynch, said Mr. McAlpin dragged a blowtorch flame across his feet while interrogating him.

People’s accounts of the raids shared striking similarities, beyond the patterns in the violence.

At least 12 of the 17 cases began as Mr. Manning’s did, with a suspect being set up by a confidential informant, someone the deputies had persuaded to stage a drug buy while they waited nearby.

In six cases, people said deputies threatened to continue assaulting them until they disclosed either the name of a drug dealer or the location of drugs. Five people said the deputies ransacked their kitchens and destroyed their food or used it to humiliate them — smashing a cake into a man’s face before arresting him, dumping flour and rice onto a kitchen floor, pouring milk into a freshly cooked dinner. Every Black accuser said deputies had hurled racial slurs at them.

Most of the targets were men in their 30s or 40s with a history of drug use. But in 2009, Mr. McAlpin knocked out 19-year-old Christopher Hillhouse’s tooth with a Maglite, he and his mother say. The next year, deputies beat and shocked Dustin Hale, then 17, until he urinated on himself while his girlfriend watched, he said. When his mother and grandmother went to the county jail to pick him up, they said, they hardly recognized him through the bruises and swelling.

The story of Jeremy Travis Paige, who was targeted in 2018, fits a typical pattern described by the accusers.

Mr. Paige, a 41-year-old with several arrests, was pulling up to his home in a working-class neighborhood outside Jackson when he realized deputies were there waiting for him, he said.

He drove away, hoping they wouldn’t notice. But Mr. McAlpin chased him and pulled him over, then deputies beat him unconscious in the intersection, Mr. Paige alleged in a lawsuit against the county.

The suit claimed that he regained consciousness as the deputies dragged him, handcuffed, into his home. Mr. McAlpin and another deputy then pummeled him in the living room for nearly an hour, according to Mr. Paige and a witness who spoke on the condition of anonymity, fearing retribution from the deputies.

In interviews, Mr. Paige said the deputies pulled him into his roommate’s bedroom and sat him upright on the bed, where he felt someone press a knee into his back and stretch a washcloth across his mouth. Then, he said, deputies poured gallon after gallon of water over his face. As he struggled to breathe, he said, one of them pressed a lit cigarette into his thigh.

All the while, they shocked his groin intermittently with Tasers, Mr. Paige said. Taser logs show that one of the four deputies who reported being at the scene triggered his Taser during the arrest.

Three people, including Mr. Paige, said they had been shocked not only with gun-shaped Tasers — the type issued by the department — but also with small, rectangular ones, suggesting that some deputies used personal stun guns that were not being tracked.

“They had the devil in them,” Mr. Paige said. “I thought they was going to kill me.”

Deputies ordered him to send Facebook messages to friends asking to buy drugs. He struck out, and the deputies took him to jail.

Before leaving, they stuffed the blood- and water-soaked bedding in trash bags and removed them from the house, Mr. Paige said.

The next day, when Mr. Paige was in jail, his son Trace visited the house. He found evidence of the violence, he said, including a bent bed frame where his father had been held down by deputies and a puddle of blood on the floor.

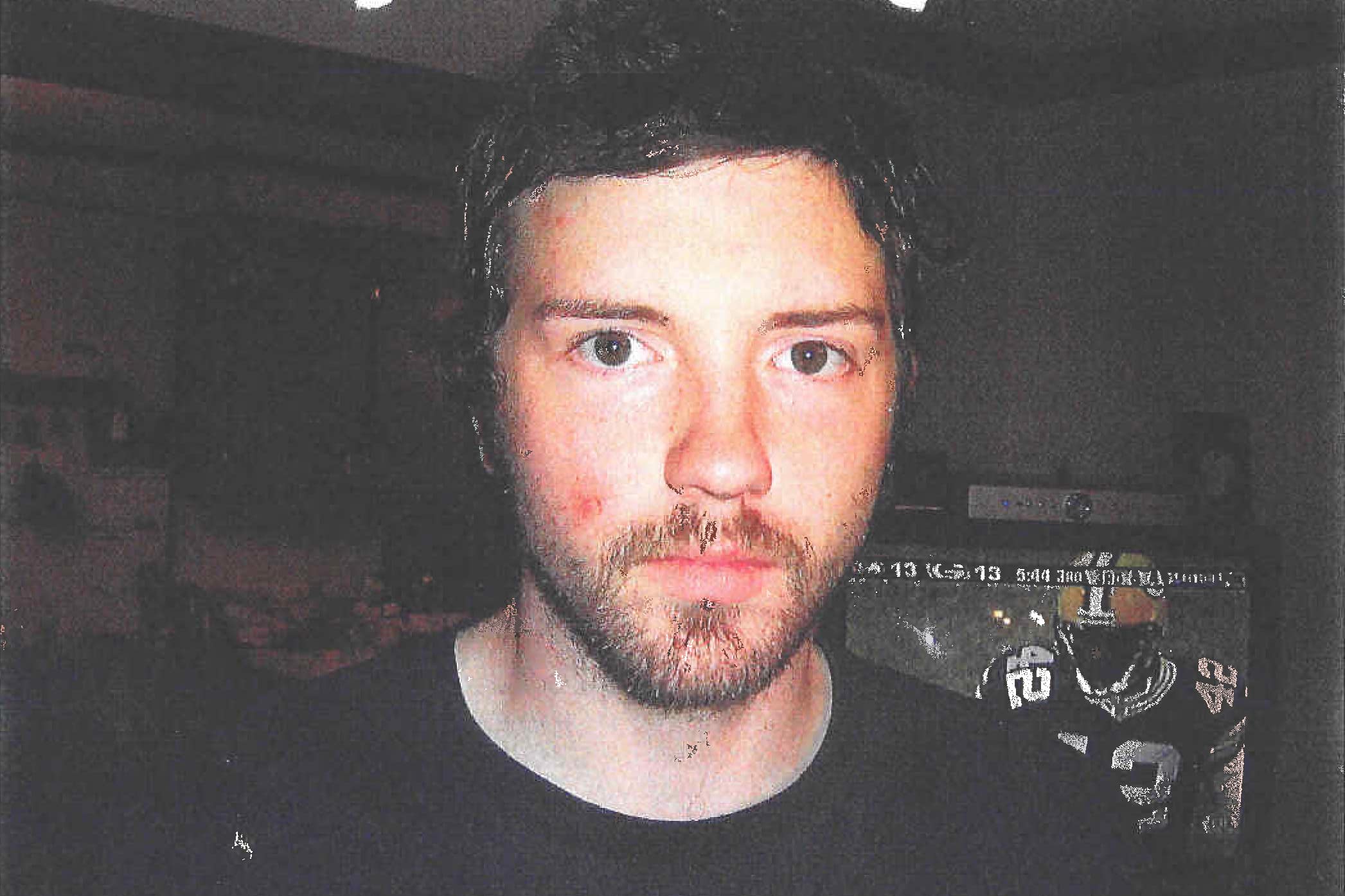

Pictures taken by Mr. Paige’s roommate show the bed stripped of linens and blood spattered on the wall.

Mr. McAlpin wrote in his report that deputies restrained Mr. Paige after he tried to kick them during the arrest, but the detective did not mention the use of Tasers or other force that might explain the blood.

During Mr. Paige’s trial for drug sale charges, Mr. McAlpin testified that deputies might have injured Mr. Paige when they pulled him out of his car, because he was resisting. He denied hurting Mr. Paige in his home.

Mr. Paige was sentenced to five years in prison. When he sued the sheriff’s department, no lawyer would take his case and he resorted to representing himself. He wrote a letter to the judge explaining that he had only a seventh-grade education.

“I don’t know how to present big words or anything like that,” he wrote. “But I do know the truth.”

After he missed several court deadlines, the judge dismissed his case.

Who Knew

Over the years, more than a dozen people have directly confronted Sheriff Bailey and his command staff about the deputies’ brutal methods, according to court records and interviews with accusers and their families.

At least five people have sued the department alleging beatings, chokings and other abuses by deputies associated with the Goon Squad.

The department settled two of those cases. Two others, including Mr. Paige’s, were dismissed over procedural errors by accusers representing themselves.

But the mounting allegations signaled that something was profoundly wrong in the narcotics unit of Sheriff Bailey’s department.

Mr. McAlpin, the department’s former chief investigator who led most of the raids reviewed by reporters, was involved in at least four arrests that prompted lawsuits, court records show.

According to one suit that was settled, Mr. McAlpin kicked 19-year-old Brett Gerhart in the face and pressed a pistol to his temple in 2010 during a mistaken raid at the wrong address. In a 2012 case, tossed out because of missed court deadlines, Gary Michael Frith claimed that he had been beaten and choked in the back of a squad car during a drug bust; records show that Mr. McAlpin was one of the arresting officers.

Mr. McAlpin also figured prominently in complaints lodged with the department. Seven people told reporters they had mailed letters, filed formal complaints or called the sheriff personally to tell him about the abuse they experienced.

Joshua Rushing said he wrote several letters to the department in 2020, after Mr. McAlpin and Mr. Dedmon drove him to an isolated dead-end road and shocked and beat him. He said he never heard back.

Nicole Brock said that when she went to the sheriff’s office to submit a formal complaint against Mr. McAlpin for ransacking her car during a search, he tore up the form, threw it in the garbage and arrested her for a syringe he had found during the car search.

Ms. Brock said she left several messages on Sheriff Bailey’s office phone to report the deputy’s behavior, but he never returned her calls.

Mr. Dare, the department lawyer, declined to provide copies of complaints, saying they were considered personnel records protected by state law. When asked to confirm the existence of the seven complaints described by accusers, he said he could not immediately provide it.

Chuck Wexler, executive director of the Police Executive Research Forum, said this long list of complaints and lawsuits should have prompted investigations by the sheriff.

“If you’re getting multiple complaints about the same officers, from different sources, that’s a red flag,” he said. “If you don’t do anything about it, you’re in denial.”

Despite the allegations against him, Mr. McAlpin continued to rise through the ranks of the department, winning Investigator of the Year and eventually being promoted to the top investigator position.

Until this year, the Rankin County Sheriff’s Department did not have anyone assigned full time to handle complaints. Instead, supervisors were responsible for investigating the deputies they oversaw, according to four former employees who spoke on the condition of anonymity because they feared retribution from the department.

Among those supervisors were Mr. McAlpin and Lieutenant Middleton, who both pleaded guilty in August for their roles in the assault of Mr. Jenkins and Mr. Parker.

On Tuesday, Sheriff Bailey announced that the department would allow residents to file complaints against deputies on the department’s website.

Beyond the lawsuits and complaints, there were other obvious signs of the violence, including injuries that would have been visible to jail workers and court officials who saw the injured shortly after their encounters.

Hospital records show that Mr. Hobson was treated for a gash over his eye after a 2018 raid in which he says deputies waterboarded him and punched him repeatedly. His face is bandaged in his jail booking photo.

Robert Jones, the man who said deputies rammed a stick down his throat, arrived at the jail with a swollen and mud-streaked face after deputies beat him and threw him into a ditch.

Many of the mug shots from the Rankin County jail feature bandaged faces, swollen cheeks and black eyes associated with drug-related arrests.

But the most glaring evidence of the violence inflicted by deputies has been collecting in the department’s computer files for more than two decades.

The Taser Logs

Every time a Taser is fired, the device keeps a record of it. In Rankin County, deputies upload this data to a computer, compiling detailed departmentwide logs that allow supervisors to monitor deputy Taser use.

The data, reviewed by The Times and Mississippi Today, contained tens of thousands of Taser triggers stretching back 24 years.

The logs supported the accounts of nine people who described being shocked by deputies while handcuffed or held down. In all but three of these cases, the deputies did not report their Taser use, violating department policy.

“I don’t believe I’ve ever come across an agency in which it would be acceptable for an officer to deploy a Taser and not report it in some way,” said Ashley Heiberger, a retired officer and an expert in police use of force.

After several studies linking prolonged Taser exposure to severe medical problems and even death, the Police Executive Research Forum developed national guidelines advising against shocking a person for more than 15 seconds during an encounter.

The logs contain dozens of instances of Tasers being fired for at least double the recommended time limit over the course of an hour. In April 2016, a device assigned to a deputy who participated in Goon Squad raids was triggered nine times in four minutes, delivering 31 seconds of current.

Several experts in police use of force said the logs showed abnormal Taser use that was hard to explain. Seth Stoughton, from the University of South Carolina, said the frequency of the deputies’ Taser triggers suggested they were not using the weapons for their intended purpose: to quickly subdue a combative person.

“It just doesn’t suggest that the Taser is actually being used to induce compliance,” he said.

By comparing the logs to department records, reporters identified four people who claim they were at the receiving end of Taser shocks recorded in the data.

In 2016, Deputy James Rayborn fired his Taser for 20 seconds over the course of 20 minutes during a raid of Samuel Carter’s home.

Mr. Carter, a 64-year-old Army veteran, had had previous run-ins with Rankin sheriff’s deputies over alleged drug use. On the night of the raid, he said, deputies dragged him to his bedroom, shocked him and demanded that he open a safe where they expected to find drugs and cash.

Instead, deputies found a tub of cake frosting he had stashed in the safe to hide from houseguests with a sweet tooth.

Mr. Carter said they became enraged and shocked him again until his leg began to bleed.

Down the hall, Christopher Holloway, a 26-year-old who had been helping Mr. Carter maintain his property, was beaten and shocked until he defecated on himself, he said. Then they dragged him outside and threatened to push him, handcuffed, into Mr. Carter’s pool.

Mr. Holloway and Mr. Carter were charged with paraphernalia and drug possession — Mr. Holloway for marijuana, Mr. Carter for several grams of methamphetamine.

Like many people targeted by Rankin deputies, Mr. Carter said the first raid was just the beginning. Three months later, deputies arrested him again, this time for drinking in front of his home, Mr. Carter said. He was arrested four more times over the next year, department records show, mostly for drug or paraphernalia possession.

Ballooning legal fees left Mr. Carter unable to pay his bills.

“They had the power,” he said. “And they used it.”

‘I Lost My Life’

The Goon Squad has left a long trail of shattered lives in its wake. Some people who said they were brutalized are jolted awake by nightmares after their encounters with deputies. Four said they fled the county for good. Several are serving lengthy prison terms.

In 2015, Ron Shinstock was struggling with a methamphetamine addiction, even as he raised a family with his wife and ran a mechanic shop with his brother.

Everything changed, he said, after Mr. McAlpin led a violent raid of his home, holding his children at gunpoint and forcing him to strip naked in his backyard. The arrest led to a 40-year prison sentence for a $260 meth sale within 1,500 feet of a church.

Mr. Shinstock’s wife left him. He is scheduled to be released in 2056, two months before his 82nd birthday.

“I lost my family, I lost my home,” Mr. Shinstock said. “I lost my life.”

Andrea Dettore, a former resident of Rankin County, witnessed deputies brutalize three people in two incidents. She said she was there in 2018 when the Goon Squad attacked Mr. Loveday, the former deputy, and Mr. Hobson.

During a raid on her own home in January, she said, she heard deputies beat her friend, Robert Grozier, behind a closed door, and saw a deputy, Christian Dedmon, shove a sex toy into his mouth, threatening to shock him with a Taser if he spat it out.

Ms. Dettore and Mr. Grozier were each fined several hundred dollars, and she has since left Rankin County. Mr. Hobson sat in jail for six months before his charges were dropped, and Mr. Loveday lost his job as a sheriff’s deputy. Court records show he was never convicted of a crime.

After Mr. McAlpin arrested Mr. Loveday and accused him of consorting with drug dealers, he ordered him to leave town. Mr. Loveday fled the state, fearing he would be targeted again. He couldn’t forget that night.

“If they did that to me, how many other people have they done it to?” he wondered.

Before he left Mississippi, Mr. Loveday said, he called Sheriff Bailey personally to warn him about his deputies’ behavior.

But Mr. Bailey wouldn’t listen, he said. He called Mr. Loveday a dirty cop and accused him of secretly recording the call.

Then, Mr. Loveday said, “He hung up on me.”

Jerry Mitchell, Ilyssa Daly, Eric Sagara and Irene Casado Sanchez contributed reporting. Kitty Bennett contributed research. This article was reported in partnership with Big Local News at Stanford University and supported in part by a grant from the Pulitzer Center.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Auditor alleges mismanagent of funds by health department

Three nonprofits received over $850,000 in federal grants for HIV prevention between 2021 and 2024 but administered only 35 HIV tests during that period, State Auditor Shad White alleges in a report released Monday.

The report identified reimbursements for alcohol, late-night rideshares, purchases from a smoke shop, the rental of a nightclub owned by one group’s executive director and a declined payment for gift cards. All of the payments were approved by the Mississippi Department of Health, the agency responsible for overseeing distribution of the funding to community-based organizations.

“The lapses identified are unacceptable and not reflective of our agency’s standards or mission,” the health department said in a press release Monday.

The agency could not produce monthly reports for grant activities or documentation of hundreds of thousands of dollars of expenses, the report said. Nor could it provide all of the funding agreements or say whether the organizations were aware they were required to report testing data, a spokesperson for the auditor’s office told Mississippi Today.

The grant funding was meant to help states establish and maintain HIV prevention and surveillance programs, and HIV testing was an element of each organization’s agreement. The grants also paid the nonprofits to educate the public about HIV and hire community health workers.

Mississippi has the sixth highest rate of new HIV diagnoses in the country, and the majority of the state’s prevention efforts are funded with federal dollars.

“It’s almost like our government hates us,” said Auditor Shad White in a press release. “This kind of spending defies all common sense and is an insult to hardworking taxpayers.”

Lorena Quiroz, the executive director of Immigrant Alliance for Justice and Equity, said the nonprofit submitted all required monthly reports and expense documentation to the health department.

Love Inside for Everyone and Love Me Unlimited 4 Life, the other two organizations investigated by the state auditor, did not respond to questions from Mississippi Today.

None of the organizations referenced in the audit report still have grants or contracts with the health department, and the agency has already taken steps to hire new leadership in its STD/HIV division and tighten management of grants, it said in a press release.

The audit probes a period when the health department’s STD/HIV division was severely understaffed after public health priorities shifted to the COVID-19 pandemic and skyrocketing syphilis cases in the state. Around the same time, the health department began receiving tens of millions of dollars in additional federal funding for HIV prevention efforts as a part of an initiative launched by President Donald Trump during his first term in office to end the domestic HIV epidemic.

But the funding increases have resulted in only a slight dent in new HIV cases. New diagnoses dropped 5% in the first three years of reported data since the state began receiving the additional federal dollars, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data published by AIDSVu – far from keeping up with the federal government’s ambitious goals of reducing new diagnoses 75% by 2025 and 90% by 2030.

Increasing HIV testing in community settings is one of the plan’s core strategies.

Immigrant Alliance for Justice and Equity, a Jackson nonprofit that advocates for immigrant and indigenous communities in Mississippi, was contracted to take steps to become a rapid HIV testing site, but did not conduct any tests because the health department did not provide a phlebotomist, Quiroz told Mississippi Today in an email.

It is unclear why the organization would have required a phlebotomist, as rapid tests are administered with a finger prick or saliva. Immigrant Alliance for Justice and Equity did not respond to a follow-up question for clarification.

Quiroz said HIV testing materials worth $11,412 were lost in a storm that destroyed the organization’s building and roof. The storm occurred in June 2023, one month before the nonprofit’s agreement with the health department ended and 10 months after the supplies were purchased.

Health department records showed that Love Inside for Everyone, a LGBT+ advocacy nonprofit, performed 35 HIV tests between 2021 and 2024.

Love Unlimited 4 Life, a transgender advocacy organization no longer in operation, recieved grant funding between 2021 and 2023 for the salaries of two community health workers. Health department records showed that no HIV tests were administered by the organization.

The nonprofits’ grant agreements also included education and testing events. The auditor’s report called several events “questionable,” including a Latinx pride month and HIV awareness event hosted by Immigrant Alliance for Justice and Equity that exceeded its proposed budget and included alcohol purchases in a request for reimbursement.

Love Inside for Everyone used grant funding to rent Metro 2.0, a nightclub owned by the organization’s executive director, Temica Morton, a possible conflict of interest.

Due to the health department’s lack of grant monitoring, it could not say if HIV testing or awareness activities occurred at the events, the auditor’s office said.

Several federal grants Mississippi relies on for HIV prevention efforts have been cut or destabilized since the Trump administration took office earlier this year. Public health experts have argued these cuts will undermine HIV testing activities.

White said the audit shows that the Trump administration’s cuts to HIV prevention efforts have been unfairly criticized in a video on Fox News Digital.

“Our audit shows that when you dig into how this money is actually being spent, it’s not actually helping people with HIV/AIDs, it’s not helping to test people for HIV, it’s instead being wasted,” White said.

The health department reiterated the importance of community partners to advancing public health goals in a statement.

“It is important to underscore that these findings do not reflect the value of many nonprofit partners we continue to work with across Mississippi. Partnerships remain critical to our public health mission.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Auditor alleges mismanagent of funds by health department appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Right

The article focuses on State Auditor Shad White’s audit of the Mississippi Department of Health’s management of federal HIV prevention funds, detailing allegations of mismanagement, misuse of funds, and a lack of oversight. The tone and framing of the piece, particularly White’s statements criticizing the health department’s actions and the Trump administration’s cuts to HIV prevention funding, suggest a critical stance towards government inefficiency. However, it also provides the health department’s response, stating the importance of community partnerships and clarifying that not all nonprofit partners are at fault. The overall presentation is fact-based but leans towards a critique of government spending and management, which aligns with a center-right perspective critical of governmental waste and inefficiency.

Mississippi Today

‘A casino in every pocket’: Mississippi illegal online sports betting thrives as legalization stalls

On the heels of the Legislature’s most recent failed attempt to legalize mobile sports betting in Mississippi, a 52-year-old gambling enthusiast named Gary drew a distinction between himself and his fellow bettors: He is a winner, and most of them are losers.

“To say it honestly, most people are losers when it comes to sports betting because they lose control. But I hope they legalize it because I have control over my gambling,” Gary said. “Certain members of my family call me a degenerate, but I guarantee you I’m not a losing sports bettor.”

Gary, whose full name Mississippi Today agreed not to publish so he could speak candidly about placing illegal sports bets, is among the Mississippi residents who have together placed, according to some analysts, billions of dollars in online sports bets through illicit offshore betting platforms. He is also among the dozens of people who told Mississippi Today, in a written survey and interviews, about what legalization would mean for those who currently bet illegally.

What emerged is a portrait of the state’s shadow sports betting economy alongside growing concern among experts about the potential for gambling addiction.

A thriving black market

The push to legalize mobile sports betting in Mississippi has prompted a debate that has captured the attention of powerful moneyed interests and ordinary citizens alike. It has unfolded in bustling casinos on the Coast, church pews in the Delta and the group text chains of sports-obsessed college students.

Favorable regulatory and technological shifts have led to rapid growth for the online gambling market in recent years. But the industry continues to be undercut by illegal operators. Online gross gaming revenue in the U.S. topped $90 billion in 2024, $67 billion of which went to unlicensed players, according to research commissioned by the Campaign for Fairer Gambling, a group that lobbies against illegal gambling.

Mobile sports betting statewide has remained illegal in Mississippi, largely due to fears that legalization could harm the bottom line of the state’s casinos and increase gambling addiction. In 2024, illegal online betting in Mississippi made up about 5% of the national illegal market, which is about $3 billion in illegal bets in Mississippi, proponents said that year.

From the start of the most recent NFL season to about March, Mississippi had recorded 8.69 million failed attempts to access legal mobile sportsbooks in other states, according to materials presented to House members at a legislative meeting.

Those who engage in illegal online sports gambling and spoke to Mississippi Today described a black market that bridges newfangled technologies with the illicit gambling practices of yesteryear. Some use “arbitrage betting tools” and virtual private networks, or VPNs, to bet across the globe on different sites, pitting casinos against each other. Others keep themselves a degree removed from placing bets directly, using “bookies” to place bets on offshore gambling sites.

However people place illegal sports bets, the persistence of a thriving black market and an estimated $40 million to $80 million a year in tax revenue legal sports betting could bring in has prompted a fierce push for lawmakers to legalize the practice. The sports gambling lobby, as it has done in other states, has spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on Mississippi politicians trying to win the Legislature’s support.

The Mississippi House in 2023 and 2024 passed legislation legalizing online betting, but it died in the Senate.

Some form of sports betting is legal in 40 states, though only 20 have full online betting with multiple operators, according to Action Network, a sports betting application and news site. Some states have only in-person betting, and some only have a single online operator. Mississippi permits sports betting, but it only allows bets made in person at casinos or bets made with apps on mobile devices while inside casinos.

That is how Greg, 38, placed his bets in Mississippi.

‘Hyper-targeted victimization’

Greg earned his master’s degree at Delta State University in Cleveland, Mississippi. When he was a student, Greg would make the roughly one-hour drive north to Tunica, home of several casinos along the Mississippi River. The area was one of the first to capitalize after Mississippi enacted the Mississippi Gaming Control Act in the early 1990s, which legalized dockside casino gambling.

For Greg, driving through the rural Delta landscape to a casino was as a guardrail against over-indulgence, one that has been lost with the advent of smartphones and easy access to offshore betting platforms.

“That’s a conscious effort, that you think the whole way, ‘is that money you need to be gambling or losing, versus (now) when you’re dialing it up on your phone,” he said.

Greg has since moved to Kansas, a state that fully legalized mobile sports betting. He now bets on football and college basketball two to four times a week with wagers ranging from $55 to $500. He places bets on three different apps, all of which compete with special promotions enticing him to return. These deals are not typically matched by brick-and-mortar casinos

“I can’t imagine walking into the Horseshoe in Tunica and them saying, bet $100 cash and we’ll give you a free $50.”

Online betting is conducive to marketing campaigns that are precise in their execution and relentless in their frequency, experts told Mississippi Today. The rise of mobile sports betting has been accompanied by the introduction of new technologies in advertising and marketing, including those buoyed by artificial intelligence.

“You can absorb their betting patterns and use AI to predict when to send that notification reminding them to place a bet,” said Dan Durkin, an Associate Professor of Social Work at the University of Mississippi. “It’s hyper-targeted victimization, let’s just call it what it is.”

Durkin is chair of the steering committee for the Coalition on Intercollegiate Athletics, an organization that works to promote student well-being in intercollegiate athletics. The coalition has monitored the spread of mobile sports betting as college campuses have become hubs of activity for sports betting and, increasingly, gambling addiction.

According to a 2023 survey conducted by the National Collegiate Athletic Association, sports wagering is pervasive among college students, with 67% of students betting on sports. Nearly 60% of students are likely to bet on sports after seeing an advertisement, the survey found.

And more than 60% engaged in sports gambling are betting on sports using highly addictive “in game/micro bets.” This type of betting allows users to wager on specific in-game moments, such as the next football play or golf swing. That sort of betting would become easier if sports betting is legalized because, under current law, many bettors say they still rely on bookies to place bets on offshore gambling sites for them.

These forms of online gambling, made seamless and accessible through digital apps, can allow addiction to fly under the radar.

Gambling addiction has the highest suicide rate of any addiction disorder, according to the National Institutes of Health. The disorder’s ability to fester in private makes intervention more daunting, Durkin said.

PODCAST: Mississippi citizens often left in the dark on special-interest lobbying of politicians

“If you have a drug problem, you are going to have physical symptoms. If you have an alcohol problem, you are going to have physical symptoms. Gambling disorder can remain hidden for a very long time. Most of the folks that have it stay very functional,” Durkin said.

“Until they’re not.”

‘Gambler is going to find a way to bet’

For some students, the appeal of mobile sports betting stems not from cleverly-constructed digital marketing schemes, but as a source of camaraderie.

Cole, a 19-year-old college student, likes to bet on soccer and March Madness and the NBA Playoffs. He and a group of friends recently placed bets on the Master’s golf tournament

“It’s fun to do with your friends cause you’re all watching the game together, you get that adrenaline rush, and you celebrate together,” he said. “It’s not life-changing money, it’s mostly a social thing.”

Nevertheless, some Mississippi universities have become so alarmed by the rise of online gambling on their campuses, they are taking steps to prepare for increased addiction, even as mobile sports betting remains illegal. In Oxford, the University of Mississippi plans to hire a gambling clinician to help students struggling with addiction, according to The Daily Mississippian.

Influential religious institutions in Mississippi, a Bible Belt state, have long opposed the spread of gambling, a stance many retained as mobile sports betting came before the Legislature.

During the 2025 legislative session, David Tipton, District Superintendent for the Mississippi District United Pentecostal Church, sent a letter to the Mississippi Legislature opposing legalization on the grounds that it would harm young people in particular.

“The introduction of mobile sports betting would represent the most significant expansion of gambling in Mississippi since the legalization of casinos over thirty years ago,” Tipton wrote. “This development would effectively place a casino in the pocket of every Mississippian, creating new challenges, particularly for our youth and young adults who are the most vulnerable to gambling-related harm.”

Mississippi is one of the poorest states in the country, and the extent to which that calls for an added layer of caution lies at the heart of the debate between proponents and opponents of legalization.

“I’m a libertarian. It’s not my job to tell people how to live their life,” said Gary, the 52-year-old sports gambler. “If you can’t control yourself, I’m sorry, learn some control. Is that brutal? Probably, yes. If you want help, there’s way to get help. You can self-ban yourself.”

READ MORE: Questions to ask Mississippi lawmakers about transparency, ethics, special-interest money

Gary says every gambler is responsible for managing their own “leak.”

The term often refers to a consistent weakness in a bettor’s strategy, but Gary also uses it to connote a weakness of will.

“Every gambler has a leak, as we call them. Drugs, women, money, strippers, or the dice table, which was my leak. I could win every sports bet, but I’m going to walk through the casino and go to the dice table and lose money on a dice table,” Gary said.

“The Legislature, in their great, infinite wisdom, where they say they are protecting people, they’re not protecting anybody except casinos. A gambler is going to find a way to bet.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

The post 'A casino in every pocket': Mississippi illegal online sports betting thrives as legalization stalls appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

This article presents a balanced view of the debate surrounding mobile sports betting in Mississippi. It reports on both the arguments for and against legalization without strongly endorsing one side over the other. The piece discusses the perspectives of individuals, including sports bettors and opponents from religious institutions, as well as financial considerations and public health concerns. While there are references to lobbying and the role of lawmakers, the article primarily focuses on providing a factual overview of the situation without exhibiting clear ideological leaning. The language remains neutral and factual throughout the piece.

Mississippi Today

Mental health cuts threaten program for moms

DUBLIN — Pregnant with her second child and entering addiction treatment at a Coahoma County residential program in 2019, Katiee Evans worried she had ruined her life beyond repair. The Columbus native had struggled for years with methamphetamine addiction, a disorder that led the state to take custody of her then-7-month-old daughter.

Evans didn’t complete treatment after giving birth to her first child, but the prospect of remaining with her newborn motivated her to try it again. This time, she stayed sober during her second pregnancy – which she credits to being surrounded by dozens of other new parents going through the program, many of whom had their children with them.

“I got to love on my baby, and everybody else’s baby,” she said.

Since then, Evans has reunited with her first child, given birth to a third baby and stayed sober. She now works for Fairland, the addiction treatment center that served her, helping to administer the program she credits with stabilizing her life.

But a major source of funding for this program has been cut. In March, the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration abruptly stopped distributing billions of public health dollars across the country. About $4.1 million of that was for Mississippi’s community mental health centers, organizations across the state that run services including the addiction treatment program Evans attended.

A federal district judge has temporarily blocked the cuts, but the ruling only applies to the 23 states that sued the federal government, not Mississippi.

“This announcement caught us off guard,” said Adam Moore, a spokesperson for the Mississippi Department of Mental Health, the agency that administers state and federal funds to the centers.

The centers’ services — including crisis response teams, adolescent support and development disability programs — are available regardless of people’s ability to pay. That’s possible in large part, center directors say, because of funds like the halted grants. Moore said that about 43% of the dollars the state’s mental health department provided centers in the 2024 fiscal year came from the federal government.

A spokesperson for the federal government’s mental health agency said Mississippi’s money was granted to address the pandemic, which is no longer a threat to the U.S. She said a new federal agency called the Administration for a Healthy America will prioritize mental health efforts.

The Region 6 center, which serves much of the Delta and runs the Fairland clinic, is expected to lose out on just over $850,000 in federal funds, according to the Mississippi Department of Mental Health.

Part of the program that provided financial assistance for mothers and children to transition to independent housing had to be shut down in March as a result of the loss of funding. Phaedre Cole, the region’s executive director and Mississippi Association of Community Mental Health Centers president, said she’s uncertain whether the state agency would replace the money for that service.

Joanne Shedd, a Fairland peer support specialist who also completed treatment at the center, said it can be nearly impossible to find housing options for new mothers and their children without that additional resource.

“Our whole game plan that we have with these clients has got to completely change,” she said.

CMHCs struggled to stay afloat before federal cuts

Mississippi’s community mental health centers have struggled to fund their services for years. Four have closed since 2012. Cole said consolidations have created more financial strain on her center, which has grown from serving eight to 16 counties over the past dozen years.

Another four of the remaining 11 centers have little on-hand money to buffer any funding losses, according to the Mississippi Office of the Coordinator of Mental Health Accessibility’s latest quarterly report.

Cole said much of this financial instability comes from the responsibilities of community mental health centers: the Department of Mental Health tasks them with being the “primary service providers of outpatient community-based services” for kids and adults with mental health needs in every county they serve.

“No one’s providing those safety net services that we provide,” Cole said.

That means they maintain programs that are critical but expensive, including crisis stabilization unit beds and the Fairland program.

While Cole said the maternal substance use program is costly, it addresses a disorder that can lead babies to be born prematurely, underweight and with birth defects if untreated. Substance use is also the second leading cause of Mississippi’s pregnancy-related deaths, according to the state’s most recent maternal mortality report.

The Delta, where Fairland is located, has the highest rates in the state of mothers dying during pregnancy and the postpartum periods.

In Oxford, Melody Madaris leads Communicare, the Region 2 Community Mental Health Center for six Mississippi counties. She said the majority of Communicare’s patients can’t pay for the center’s services, and her organization provided nearly $7 million of free care last year.

Because the organization relies heavily on federal funds, Madaris was shocked when she found out the federal mental health agency stopped hundreds of thousands of dollars Communicare was set to receive.

“It was absolutely terrifying,” she said. “Within a day, we started looking at our budget and how we can continue to provide services at the same level.”

Communicare is now unable to staff a diversion coordinator, an employee dedicated to working with judges overseeing mental illness-related civil commitment cases. The diversion coordinator helped people in this position and their family members determine if the person could get treatment in a community setting and avoid state hospital commitment.

It’s the type of service the Department of Justice accused Mississippi of not doing enough of in its seven-year lawsuit against the state’s Department of Mental Health. Although the lawsuit was overturned in 2023, the mental health department’s executive director has said avoiding unnecessary hospitalizations remains a priority for the agency.

“A lot of CMHCs had a lot of success with that role,” Madaris said. “When the federal government stopped those grants, that role stopped.”

Moore, the Mississippi mental health department’s spokesperson, said the agency continues to fund 33 similar roles, called court liaisons, across the state. He also said the agency plans to use state alcohol tax revenue and other federal grant funds to try to fill the gaps, but there’s not enough to fully cover the lost dollars.

“You can backfill and keep things going on a short term basis,” said Mississippi Senate Public Health Committee Chairman Hob Bryan, D-Amory. “But long term, if the federal funding goes away, then those services are going to go away.”

State House Public Health and Human Services Committee Chairman Sam Creekmore, R-New Albany, said he and other state lawmakers had assumed these funds would be available until September.

“It does not seem fair,” he said. “We have a real, real need for mental health services in Mississippi, and I hate that this has happened. But it kind of seems par for the course, the way things are going with this Trump Administration right now.”

Creekmore noted that in its last regular session, the Legislature passed a law that instructs the state to apply for a federal community mental health payment model that allows Medicaid to reimburse more for services. But it’s up to the federal government to approve Mississippi’s application.

‘This is life or death for people’

Cole, the Region 6 executive director, said it would dramatically help Community Health Center operations if Mississippi’s application is approved next year. But she worries more drastic cuts could be coming – ones that would cripple the centers completely.

She said centers like Region 6 receive other funding from the American Rescue Plan Act, a source of federal COVID-19 relief funds, and those contracts are set to end next year. If that money is also canceled, Cole said the state mental health centers would likely have to cut more services.

Additionally, the U.S. House of Representatives has adopted a resolution to cut $880 billion over the next 10 years from agencies including Medicaid, the federal and state partnership that provides health insurance to over half a million Mississippians. Cole said Region 6 receives over half its funding from Medicaid, and any cuts to the program could be “disastrous” for community mental health centers.

For Evans, the Columbus mother who was treated at Fairland, she wishes decision makers would visit Mississippi’s Community Mental Health Centers before cutting their funding.

While people treated there, like those with severe mental illness, can’t always travel to Washington to advocate for themselves, she said it’s easy to see the deep impact programs like the one that saved her life have once one is inside the building.

“This is life or death for people. There’s no other way around it.”

Community Health Reporter Gwen Dilworth contributed to this story.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

The post Mental health cuts threaten program for moms appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article presents a sympathetic portrayal of the impact of federal mental health funding cuts on vulnerable populations in Mississippi, particularly mothers recovering from addiction. The narrative centers on personal stories and expert commentary to emphasize the value of these programs and the risks of defunding them. While it includes criticism of the Trump Administration’s policies—particularly a quote blaming the current administration—it largely focuses on reporting factual developments and quotes from stakeholders. The framing, however, tends to highlight the negative consequences of conservative policy decisions, aligning it with a Center-Left perspective.

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed3 days ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed3 days agoMissouri family, two Oklahoma teens among 8 killed in Franklin County crash

-

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed6 days agoSmall town library in WV closes after 50 years

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed2 days ago

News from the South - Georgia News Feed2 days agoMotel in Roswell shutters after underage human trafficking sting | FOX 5 News

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed7 days ago2 killed, 6 others injured in crash on Hwy 210 in Harnett County

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Texas News Feed6 days agoFamily seeks justice for father’s mysterious murder in NW Harris County

-

Local News7 days ago

Local News7 days agoNorth Gulfport Elementary & Middle School pre-registration for PreK4ward now open

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days agoStates Push Medicaid Work Rules, but Few Programs Help Enrollees Find Jobs

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed7 days agoOp-Ed: Oklahoma should tell Maryland: Let them eat crab cake | Opinion