Mississippi Today

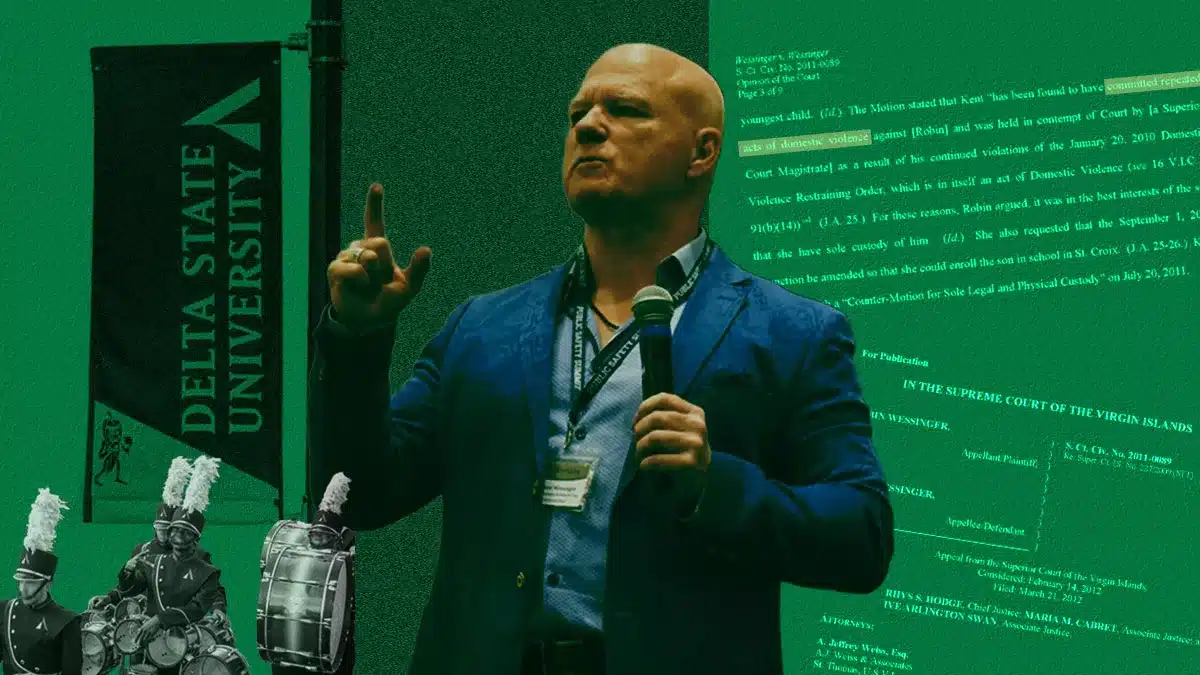

How a business consultant with a history of domestic violence allegations took over the Delta State music department

CLEVELAND — It was the fourth day of classes at Delta State University last fall when the dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, Ellen Green, asked the music department to not hate her forever.

The 12 faculty members had just experienced one of the most tragic things to ever happen at the tiny college in the Mississippi Delta. Their department chair, Karen Fosheim, had been beaten to death in her home. Her stepson, then 14 years old, confessed to killing her.

It was on Green to hire a new chair for the grieving department. That day in August, she said she’d finally settled on someone to do it: Kent Wessinger, Ph.D.

A self-proclaimed “people scientist,” Wessinger has been called by one professional development group the “world’s foremost authority on workforce trends and solutions.” The tagline for his consulting company, the Florida-based Retention Partners, which focuses on millennials in the workforce, is “attract, engage and retain.”

He had been the headmaster of a missionary school in Jamaica, a program coordinator at the University of the Virgin Islands, and a visiting faculty member in entrepreneurship at a university in Belize, where in 2018 or so he says he struck up a friendship with Andy Novobilski, who’d go on to become Delta State’s provost. Novobilski announced in August that he was stepping down.

But Wessinger was not a musician. He was not even a tenured faculty member at Delta State or any university. According to his LinkedIn profile, he had never run a university department.

Green acknowledged it was “highly unusual.” That’s why the university planned for Wessinger to have a co-chair, a music faculty member who he’d simultaneously train to eventually take over full leadership of the department.

“He is a people person,” Green said, according to a recording of the meeting. “He is very likable. I found him to be — how do I put this? He likes building relationships. He understands what we do is all based on relationships.”

Despite Wessinger’s professed leadership expertise, his year helping lead the embattled music department did not raise morale or build bonds between faculty and students, but rather further grieved faculty who already feared for the department’s future, according to interviews with more than 16 faculty and current and former students. Multiple people asked not to be named, fearing retaliation.

Wessinger’s legacy in the department goes beyond personal or professional disagreements. He has been accused of domestic violence — a fact that, once uncovered, didn’t sit well with faculty still rattled by Fosheim’s killing.

His appointment raises a crucial question: Did Delta bring in the right person to lead its respected music department, and did it do enough — or anything — to vet him? And, if it did know about the past claims against Wessinger, what was Delta State’s responsibility to inform its faculty and students after the trauma they had suffered?

For some faculty, Wessinger’s decisions as department chair — made with the administration’s support — were possibly career-ending. He was involved in an attempted firing of the tenured band director, Erik Richards, a decision that a university committee recommended be overturned. He recommended denying tenure to an award-winning vocal teacher, Jamie Dahman, based in part on what Wessinger admitted, in his denial letter, was speculation.

A third faculty member who asked to not be named was reprimanded by the dean for unacceptable conduct and saying Wessinger had been accused of domestic violence, which the dean called “defamatory,” according to a letter the faculty member sent to Human Resources.

Students were also affected by the seeming disarray. In at least one instance, Wessinger took standard student complaints to human resources instead of following the typical process in higher education: To run them up the academic chain.

“The entire music department and the faculty were already mourning Dr. Fosheim, and now I feel like it’s just been constantly going downhill ever since she died,” said Lexie Johnson, a fifth-year music education major. “We just can’t catch a break.”

For his part, Wessinger says that every decision he made was for the students and in consultation with Julia Thorn, his co-chair. After granting an interview to Mississippi Today in July, he stopped discussing matters related to the university, claiming Delta State had instructed him and other administrators to “have no further contact with the press.”

“All of those decisions were made out of one single spirit and that spirit was for the students,” he said in July. “We don’t want this department to die.”

Delta State declined to comment on a majority of Mississippi Today’s inquiries, responding only to three questions a spokesperson said were not about “confidential personnel matters.”

Wessinger’s controversial handling of the department comes as Delta State is experiencing an employee retention problem. Since 2018, it has lost 46 faculty members, more than any other public university in the state, according to data from the Institutions of Higher Learning. Last school year, multiple departments were helmed by interim chairs, though music was the only one where an interim wasn’t an expert in its speciality.

And IHL recently cited one music degree for producing few graduates, putting it at risk of shutting down.

“If it doesn’t work with Dr. Wessinger, it’s four months, okay?” Green told the faculty. “This is very, very temporary.”

The Heartbeat of the Department

Like much at Delta State, the music department has seen better days.

Its building, Zeigel Hall, which sits on the campus’ historic quadrangle, in recent years has been plagued by asbestos and a faulty elevator that’s known to trap students for hours at a time.

The instruments are aging. The enrollment has shrunk. The band used to be renowned for producing band directors, but nowadays, students go to other schools, seeking the pomp of a traveling SEC game or the bravado of the Sonic Boom of the South.

In the midst of this challenge was Karen Fosheim. She was, students and faculty say, the heartbeat of the department. A pianist who became chair in 2016, she had a preternatural ability for knowing what was going on in the department at all times, many said, attending every concert and remembering the names of every student.

She was also skilled at uniting people, the chair’s most important role, recalled Mary Lenn Buchanan, Fosheim’s close friend and a retired Delta State music professor.

This was important because musicians have notorious egos. And there was already a rift in the music department. In 2019, Richards, the band director, received tenure despite opposition from some music faculty. The disagreement had dogged Zeigel Hall ever since.

But Fosheim commanded respect, Buchanan said, by always telling the truth.

“Unless Karen needed to tell someone they were pretty and they really weren’t, she did not lie,” Buchanan said.

Fosheim also directed that straightforwardness toward Delta State’s administration, especially during the pandemic, which may not have endeared her to them. By last summer, a rumor was circulating that Fosheim was going to be replaced.

The week of June 14, 2022, Fosheim didn’t show up for a scheduled work performance.

That day, concerned faculty asked the university police to request a wellness check on her home in Boyle, a small town just south of Cleveland. Her husband was out of state, and though Fosheim had been responding to texts, the replies were strange, unlike her.

Worried that Fosheim’s stepson, Alseny Camara, who is Black, would feel unsafe around police, two faculty members drove over that afternoon. They walked through the home with a detective. It was freezing inside and smelled.

Fosheim’s bedroom door was locked. The officer said he could get in via a window. As he removed the screen and peered through the glass, he saw a body prone on the floor.

That’s when Camara ran, according to testimony from a Bolivar County sheriff’s deputy during an August circuit court hearing. Deputies using K-9s found him shortly after 9:30 p.m., hiding in the woods near Fosheim’s home.

At the precinct, Camara confessed to killing his stepmom with an aluminum baseball bat. He was upset Fosheim, who was 57, had scolded him for trying to get out of his shift at a pet motel, according to the court hearing. He admitted he had impersonated her over text.

Jamie Dahman, then an assistant professor of music, had checked on Camara that day while Fosheim was still considered missing.

It still haunts Dahman that while he was talking to Camara, Fosheim was dead on the floor of her bedroom. It “sat with me for a long time,” he said, “and it still kind of gives me chills.”

As school was about to start two months later, the chair’s office was still full of Fosheim’s things: Half-finished crochet projects, potted plants, Nerf guns and foam darts, a picture of her stepson. Her voice was still on the answering machine. Her university memorial service still had to be planned.

If that weren’t enough, the Institutions of Higher Learning Board of Trustees had suddenly fired the president, William LaForge, sparking fears of budget cuts across the cash-strapped university.

And the music faculty still hadn’t heard from the administration about who would lead the department. The lack of leadership was becoming a problem. An important lock in the building wasn’t working. A new sound engineer needed to be hired.

Frustrated, Dahman sent an email to the department. He cc’d the dean, Green, and the provost, Novobilski. Since Novobilski, whose background is in business, came to Delta State in 2021, he had earned a reputation as a stickler for the hierarchy of academia.

The email got their attention. On Friday, Aug. 12, Green and Novobilski met with faculty.

A recording of the department meeting, the first without Fosheim, shows it was tense from the start. Voices were strained and shaky. Their anxiety stemmed from the stakes: Chairs have immense power in a department. Everyone wanted to trust that whoever took the role would be on their side. But faculty were worried administration, particularly Novobilski, had already come up with a plan for the role without them.

When Novobilski began the meeting, he seemed to confirm that fear by noting he had in fact been working to replace Fosheim. He acknowledged he should have called a meeting over the summer.

Dahman loudly interrupted him: “May I ask why we weren’t informed of what was going on?”

Then, a back-and-forth ensued. Novobilski told Dahman to take a deep breath.

It ended when Green asked if other faculty wanted to speak. One teared up explaining that he would have felt guilty volunteering for the vacant role. Another said that without Fosheim, the atmosphere in the department felt more toxic than ever.

Finally, Novobilski intimated he thought the department could benefit from someone outside “the music community” given its history of division.

“I have someone in mind, I’ll be honest with you,” Novobilski said. “This is someone I have worked with. … He has a lot of experience working with conflict resolution, mediation and he brings a lot of experience working with different groups of people, plus he’s a listener.”

This person, Novobilski said, did have administrative experience at the “college level.” But his specialty was business.

Dahman groaned.

Faculty barely trusted a colleague to take the job — let alone a non-musician. One faculty member protested that he thought the department could make it work with an internal hire. Josh Armstrong, then the faculty senate president, said “this definitely feels much more like here’s your new boss, and here you go.”

If faculty weren’t happy with Wessinger by the end of the semester, Novobilski conceded, “we’ll put him to work doing something else.”

But his mind seemed made up. Wessinger would be on campus by the end of August.

‘People Crisis’

About eight years ago, Wessinger set out on a mission to understand the relationship between millennials and organizational structures.

Ever since, the 59-year old Georgia native says he’s been trying to help Fortune 500 companies, churches, regional banks, rotary clubs and insurance companies — that is, “anyone who would listen” to him — solve their workforce crisis.

“I’m not just about identifying the problem,” he says in a January 2022 YouTube video titled “People crisis.” “I want to be the guy who helps you to understand what’s going on but also provides sustainable solutions for you.”

When faculty scanned his LinkedIn, Wessinger appeared impressive at first. He was a keynote speaker at more than 30 conferences a year, the author of three books and the creator of a proprietary database on millennials. His companies had ambitious names — Create2Elevate, Generational Forces, Retention Partners.

After a closer look, faculty didn’t understand how an accomplished business consultant had time to uproot to the Mississippi Delta.

Most notably, his experience in higher education was patchy. The administrative work Novobilski referenced at the Aug. 12 meeting appears to have primarily consisted of Wessinger setting up a satellite campus of the University of the Virgin Islands that offered remote classes, according to his LinkedIn.

They also discovered something particularly troubling. A 2012 opinion from the Supreme Court of the Virgin Islands in a divorce proceeding with an ex-wife, Robin Wessinger.

One line from the third page caught their eye: “The Motion stated that Kent ‘has been found to have committed repeated acts of domestic violence against [Robin] and was held in contempt of Court by [a Superior Court Magistrate] as a result of his continued violations of the January 20, 2010 Domestic Violence Restraining Order, which is in itself an act of Domestic Violence.”

This concerned faculty, who were still reeling from Fosheim’s death. It made many of them distrust Wessinger from the beginning.

Many students didn’t meet Wessinger until mid-October, almost two months into the semester, when he spoke to the recital class, according to an email.

Piper Gillam, a fifth-year music education major, said it “felt like a sales pitch.” Gillam said he called the students in the department, who were mainly born after 2000, “millennials.”

“In my head I was like, ‘I’m not a millennial. I’m Gen-Z,’” Gillam said. “And he was like, ‘and I know what you guys are thinking,’ and I was like, ‘OK, thank God, he’s gonna correct me,’ and he was like, ‘but you guys are millennials.’ So I googled it to see what age group am I, and it said Gen-Z, and I was like, alright, alright. I’m not trusting this man.”

Wessinger ran the music department like it was a business.

Faculty said he ignored their emails. But when they sought him out, they said he was hard to find in his office. Some meetings that Fosheim had scheduled months in advance now came with a few-hours notice from the department secretary. One faculty member said Wessinger neglected to notify them about a key deadline related to their tenure portfolio.

His lack of music knowledge was obvious, faculty said. He didn’t know what a “tone-row,” a basic composition method, was. He mispronounced the word “viola.”

“He said, ‘Vye-Ola,’” Richards recalled. “As in Davis.”

It didn’t make faculty feel like Wessinger was qualified to assess their work. In December, with evaluations around the corner, Green extended Wessinger’s part-time contract through the spring.

By then, faculty’s relationship with Wessinger had gotten so toxic, some started recording their interactions with him.

Wessinger seemed to have soured, too. According to sources close to Wessinger, and a text message sent on Oct. 18 by a faculty member to Wessinger’s co-chair, he started saying that Fosheim had left a “mess” in the department that he was going to “clean up.”

His prime target was Richards, the band director. A blunt and, by his own admission, polarizing figure in the department, Richards said he had questioned Wessinger when they first met. He wanted to know more about Wessinger’s dissertation on how limited opportunities for creativity in the Caribbean contributes to the region’s socio-economic crisis. It has several misspellings, including the name of a Haitian town.

Wessinger, according to sources close to him, talked openly about how he did not like Richards, who had other detractors as well.

On Feb. 22, Wessinger placed Richards on administrative leave pending an investigation into his “alleged contumacious conduct” – or as Webster’s dictionary defines it, “stubbornly disobedient” conduct.

About a month later, Lisa Giger, the human resources director, met with Richards’ wind ensemble class, according to a text message. She spent the session asking about the atmosphere of the class, multiple students said, and when they mentioned Richards, she had follow up questions.

Then on April 10, Richards received a letter from Novobilski: After a “thorough investigation by the Human Resources Department,” Richards was fired.

A university committee ultimately found that while Novobilski’s letter listed a slew of student and faculty complaints against Richards, only one had ever been formally documented. The previous administration had investigated and resolved that complaint in 2018-2019.

The thorough investigation, the committee wrote, seemed “one-sided,” but the committee couldn’t confirm that appearance because Richards was not allowed to ask any questions, which appears to be a violation of Delta State’s policies.

It is “completely outside of what is considered normal” for human resources to get involved in student complaints, said Daniel Durkin, a University of Mississippi professor and the president of the United Faculty Senate Association of Mississippi.

It is also “very unusual,” Durkin said, for someone like Wessinger who has not achieved tenure to evaluate applications for the prestigious distinction.

But that’s what Wessinger proceeded to do.

That spring, Dahman, the faculty member who was close to Fosheim, was considered for tenure. His application would become another piece of collateral damage in Wessinger’s drive to clean up the department.

Dahman, a vocal teacher who researches Bulgarian art song, had lots of reasons to be confident. In seven years of teaching at Delta State, he had never received a low mark on his annual evaluations, according to his tenure application. He’d earned a Mississippi Humanities Council Teaching Award in 2019. His students were accepted into graduate programs, won national competitions and sang in churches and funeral homes.

And chance was on his side. Most people who apply for tenure at Delta State end up getting it, according to an analysis of IHL data.

That’s why when Dahman was offered an extension on his tenure application in the fall, he did not accept it. In retrospect, he wonders if he should have. Dahman had received a verbal reprimand after his behavior at the Aug. 12 meeting, then he was put on a performance improvement plan in December. The plan required him to demonstrate “collegiality” with students, faculty, administration and campus visitors.

In late January, the department’s tenure committee, a panel of Dahman’s peers, recommended that Dahman receive tenure, and raised only minor concerns.

Then in mid-February, Wessinger recommended Dahman be denied on the basis of his teaching and collegiality, speculating there were more “violations” than the committee knew of. Two days later, Green, the dean, also recommended denial, claiming Dahman had “aggressively pounded the table” during the Aug. 12 meeting, an allegation that is not substantiated by the recording.

Dahman was devastated and angry.

His feelings spilled into his annual evaluation with Wessinger and Thorn in March. Wessinger began by asking if he could record due to the “environment” in the department, not knowing Dahman was recording as well.

Then, Wessinger revealed that he had recently taken Dahman’s students to HR and told them Dahman was on a performance improvement plan, something meant to be confidential. The students had complained about a remark Dahman had made in defense of his teaching — yet another issue that should have been resolved without HR.

Wessinger topped off the meeting by giving Dahman low marks for teaching and service. Dahman protested, but there was nothing he could do.

“This is my life, this is my livelihood, it’s how I support my children,” Dahman told them. “I feel like I’m being unfairly targeted because I snapped at the provost.”

Deconstructing hope

As the fall semester starts, many students and faculty say the music department is still struggling to get out of Wessinger’s shadow, even as he has moved on to lead a new department.

In June, Novobilski announced that Wessinger was going to be the interim chair of the Division of Management, Marketing and Business Administration.

Some faculty made a last-ditch effort to get rid of him. They sent an anonymous letter to Daniel Ennis, the new president of Delta State, summarizing their concerns with Wessinger — the adminstration’s decision to bring him on, his lack of music qualifications, the court document that said he had “committed repeated acts of domestic violence.”

Ennis didn’t respond to the letter, but even he has had to address the after-effects of decisions Wessinger had a hand in, like the hiring of Steven Hugley, the interim band director who made transphobic remarks on a podcast. Ennis also made the final call on Dahman’s tenure application, ultimately deciding to grant it.

A month later, Wessinger stood in a music room facing rows of empty risers for an interview with Mississippi Today. He talked about why he wanted to come to Delta State and how he had grown to care for it. Cleveland, he said, reminded him of the Virgin Islands — a place that needed help and where educational institutions are bastions of hope.

But some people had troubled him, deep in his soul.

“My personal issues have been accentuated to tear down and deconstruct the very opportunity that every student has here in this university,” he said, sweeping his hand out wide.

Wessinger acknowledged Fosheim’s killing had traumatized many faculty. But when he spoke about the anonymous letter, he grew agitated. He said it was full of “half truths, lies, manipulations.” He added that if Mississippi Today printed its reference to domestic violence, he was “not gonna be a happy camper.”

“We know who they are,” he said. “Anonymous, they’re not, and libel, they are.”

Yet Wessinger’s alleged past mistreatment of women goes beyond the restraining order that he violated in his divorce in the Virgin Islands, according to documents obtained by Mississippi Today.

Three other women across the U.S. have been granted restraining orders against him, all based on claims of domestic violence or mistreatment. In two of those cases, Mississippi Today confirmed through court records that Wessinger either sought or received a restraining order as well.

That was the case in Georgia, where a divorce was filed against Wessinger in 2016 in part on the basis of “fraud, cruel treatment,” which he denied. Affidavits submitted on behalf of his ex-wife, Laurie Higginbotham, allege that Wessinger wrote letters containing elaborate “false statements” that she had Huntington’s disease, and it was causing her to live in an altered state of reality.

In a phone call, Wessinger told Mississippi Today that every person who had accused him of domestic violence was “connected” and that he had believed at the time what he wrote in the letters about Higginbotham. He denied that he had ever mistreated or been violent toward a woman, adding that if he had, a judge would have taken away custody of his children.

“Attorneys will say anything in motions,” Wessinger said. “You’re reading a motion. You’re not reading the truth. You’re reading allegations. That doesn’t make it the truth.”

Faculty don’t know about the additional allegations against Wessinger, and it is unclear if Delta State’s administration knew before hiring him. The restraining orders may not have shown up on a background check since they are not public information or were hidden in court files.

Through a spokesperson, the president’s office declined to comment, citing personnel matters.

On Aug. 10, Ennis gave his first convocation.

“I’m here beside you to tackle the challenges we face, but today, put them aside and join me in celebrating what we do,” he said in his address.

Wessinger wasn’t there to hear it. He was in Florida, speaking to the CEO Council of Tampa Bay, giving a speech about solving the workforce crisis.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

On this day in 1977, Alex Haley awarded Pulitzer for ‘Roots’

April 19, 1977

Alex Haley was awarded a special Pulitzer Prize for “Roots,” which was also adapted for television.

Network executives worried that the depiction of the brutality of the slave experience might scare away viewers. Instead, 130 million Americans watched the epic miniseries, which meant that 85% of U.S. households watched the program.

The miniseries received 36 Emmy nominations and won nine. In 2016, the History Channel, Lifetime and A&E remade the miniseries, which won critical acclaim and received eight Emmy nominations.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Speaker White wants Christmas tree projects bill included in special legislative session

House Speaker Jason White sent a terse letter to Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann on Thursday, saying House leaders are frustrated with Senate leaders refusing to discuss a “Christmas tree” bill spending millions on special projects across the state.

The letter signals the two Republican leaders remain far apart on setting an overall $7 billion state budget. Bickering between the GOP leaders led to a stalemate and lawmakers ending their regular 2025 session without setting a budget. Gov. Tate Reeves plans to call them back into special session before the new budget year starts July 1 to avoid a shutdown, but wants them to have a budget mostly worked out before he does so.

White’s letter to Hosemann, which contains words in all capital letters that are underlined and italicized, said that the House wants to spend cash reserves on projects for state agencies, local communities, universities, colleges, and the Mississippi Department of Transportation.

“We believe the Senate position to NOT fund any local infrastructure projects is unreasonable,” White wrote.

The speaker in his letter noted that he and Hosemann had a meeting with the governor on Tuesday. Reeves, according to the letter, advised the two legislative leaders that if they couldn’t reach an agreement on how to disburse the surplus money, referred to as capital expense money, they should not spend any of it on infrastructure.

A spokesperson for Hosemann said the lieutenant governor has not yet reviewed the letter, and he was out of the office on Thursday working with a state agency.

“He is attending Good Friday services today, and will address any correspondence after the celebration of Easter,” the spokesperson said.

Hosemann has recently said the Legislature should set an austere budget in light of federal spending cuts coming from the Trump administration, and because state lawmakers this year passed a measure to eliminate the state income tax, the source of nearly a third of the state’s operating revenue.

Lawmakers spend capital expense money for multiple purposes, but the bulk of it — typically $200 million to $400 million a year — goes toward local projects, known as the Christmas Tree bill. Lawmakers jockey for a share of the spending for their home districts, in a process that has been called a political spoils system — areas with the most powerful lawmakers often get the largest share, not areas with the most needs. Legislative leaders often use the projects bill as either a carrot or stick to garner votes from rank and file legislators on other issues.

A Mississippi Today investigation last year revealed House Ways and Means Chairman Trey Lamar, a Republican from Sentobia, has steered tens of millions of dollars in Christmas tree spending to his district, including money to rebuild a road that runs by his north Mississippi home, renovate a nearby private country club golf course and to rebuild a tiny cul-de-sac that runs by a home he has in Jackson.

There is little oversight on how these funds are spent, and there is no requirement that lawmakers disburse the money in an equal manner or based on communities’ needs.

In the past, lawmakers borrowed money for Christmas tree bills. But state coffers have been full in recent years largely from federal pandemic aid spending, so the state has been spending its excess cash. White in his letter said the state has “ample funds” for a special projects bill.

“We, in the House, would like to sit down and have an agreement with our Senate counterparts on state agency Capital Expenditure spending AND local projects spending,” White wrote. “It is extremely important to our agencies and local governments. The ball is in your court, and the House awaits your response.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Mississippi Today

Advocate: Election is the chance for Jackson to finally launch in the spirit of Blue Origin

Editor’s note: This essay is part of Mississippi Today Ideas, a platform for thoughtful Mississippians to share fact-based ideas about our state’s past, present and future. You can read more about the section here.

As the world recently watched the successful return of Blue Origin’s historic all-women crew from space, Jackson stands grounded. The city is still grappling with problems that no rocket can solve.

But the spirit of that mission — unity, courage and collective effort — can be applied right here in our capital city. Instead of launching away, it is time to launch together toward a more just, functioning and thriving Jackson.

The upcoming mayoral runoff election on April 22 provides such an opportunity, not just for a new administration, but for a new mindset. This isn’t about endorsements. It’s about engagement.

It’s a moment for the people of Jackson and Hinds County to take a long, honest look at ourselves and ask if we have shown up for our city and worked with elected officials, instead of remaining at odds with them.

It is time to vote again — this time with deeper understanding and shared responsibility. Jackson is in crisis — and crisis won’t wait.

According to the U.S. Census projections, Jackson is the fastest-shrinking city in the United States, losing nearly 4,000 residents in a single year. That kind of loss isn’t just about numbers. It’s about hope, resources, and people’s decision to give up rather than dig in.

Add to that the long-standing issues: a crippled water system, public safety concerns, economic decline and a sense of division that often pits neighbor against neighbor, party against party and race against race.

Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba has led through these storms, facing criticism for his handling of the water crisis, staffing issues and infrastructure delays. But did officials from the city, the county and the state truly collaborate with him or did they stand at a distance, waiting to assign blame?

On the flip side, his runoff opponent, state Sen. John Horhn, who has served for more than three decades, is now seeking to lead the very city he has represented from the Capitol. Voters should examine his legislative record and ask whether he used his influence to help stabilize the administration or only to position himself for this moment.

Blaming politicians is easy. Building cities is hard. And yet that is exactly what’s needed. Jackson’s future will not be secured by a mayor alone. It will take so many of Jackson’s residents — voters, business owners, faith leaders, students, retirees, parents and young people — to move this city forward. That’s the liftoff we need.

It is time to imagine Jackson as a capital city where clean, safe drinking water flows to every home — not just after lawsuits or emergencies, but through proactive maintenance and funding from city, state and federal partnerships. The involvement of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in the effort to improve the water system gives the city leverage.

Public safety must be a guarantee and includes prevention, not just response, with funding for community-based violence interruption programs, trauma services, youth job programs and reentry support. Other cities have done this and it’s working.

Education and workforce development are real priorities, preparing young people not just for diplomas but for meaningful careers. That means investing in public schools and in partnerships with HBCUs, trade programs and businesses rooted right here.

Additionally, city services — from trash collection to pothole repair — must be reliable, transparent and equitable, regardless of zip code or income. Seamless governance is possible when everyone is at the table.

Yes, democracy works because people show up. Not just to vote once, but to attend city council meetings, serve on boards, hold leaders accountable and help shape decisions about where resources go.

This election isn’t just about who gets the title of mayor. It’s about whether Jackson gets another chance at becoming the capital city Mississippi deserves — a place that leads by example and doesn’t lag behind.

The successful Blue Origin mission didn’t happen by chance. It took coordinated effort, diverse expertise and belief in what was possible. The same is true for this city.

We are not launching into space. But we can launch a new era marked by cooperation over conflict, and by sustained civic action over short-term outrage.

On April 22, go vote. Vote not just for a person, but for a path forward because Jackson deserves liftoff. It starts with us.

Pauline Rogers is a longtime advocate for criminal justice reform and the founder of the RECH Foundation, an organization dedicated to supporting formerly incarcerated individuals as they reintegrate into society. She is a Transformative Justice Fellow through The OpEd Project Public Voices Fellowship.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

-

Mississippi Today6 days ago

Mississippi Today6 days agoLawmakers used to fail passing a budget over policy disagreement. This year, they failed over childish bickering.

-

Mississippi Today6 days ago

Mississippi Today6 days agoOn this day in 1873, La. courthouse scene of racial carnage

-

Local News7 days ago

Local News7 days agoAG Fitch and Children’s Advocacy Centers of Mississippi Announce Statewide Protocol for Child Abuse Response

-

Local News6 days ago

Local News6 days agoSouthern Miss Professor Inducted into U.S. Hydrographer Hall of Fame

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed4 days agoFoley man wins Race to the Finish as Kyle Larson gets first win of 2025 Xfinity Series at Bristol

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days agoFederal appeals court upholds ruling against Alabama panhandling laws

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days agoSevere weather has come and gone for Central Florida, but the rain went with it

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days agoBellingrath Gardens previews its first Chinese Lantern Festival