Mississippi Today

Hill Country basketball: It’s like a religion, and everyone believes

We can argue from now to next year about whether Mississippi is a football state, a basketball state, a baseball state — or, for that matter, any kind of sports state at all.

What we cannot argue is this: In northeast Mississippi, most often referred to as Hill Country, basketball is king.

Always has been. And, I would wager, always will be.

Let’s take, for example, the recent Mississippi public schools state tournament that concluded over the weekend at the Mississippi Coliseum. Fourteen state champions in seven divisions were crowned. Eight were from up in the state’s northeast corner. The only time Hill Country teams lost was when they played each other.

A quick recounting: In Class 1A, the Blue Mountain girls and the Biggersville boys were winners. In Class 2A – stop me if you’ve heard this before – Ingomar swept both the boys and girls titles. In Class 3A, the Belmont girls and Booneville boys are champions, and the Booneville girls lost by one point to Belmont. In Class 4A, Tishomingo County’s girls easily won the crown, and in Class 7A, Tupelo’s girls won it all.

You will note that nearly all the Hill Country champions are from the MHSAA’s smaller divisions, and there’s a reason. For the most part, northeast Mississippi schools have just said “no” to consolidation. And that has a lot to do with basketball, or more specifically, with the pride the small towns and communities have in their basketball teams.

“Basketball is almost like a religion up there,” says MHSAA executive director Rickey Neaves, and he should know. Neaves played at Saltillo and coached, taught and was an administrator at Booneville. “That’s the way people are raised. It’s in their blood. There are basketball goals in every yard, every park and any place, really, that’s level enough to dribble a ball.”

Neaves knows because it is in his blood, too.

These words are written by a guy from Hattiesburg, nearly at the other end of the state. But they are also written by a guy who learned to read by reading the sports sections of daily newspapers, especially the scoreboard pages with all the scores and statistics in small print. And I can remember picking up the Jackson newspapers back in the 1950s when I was learning to read and being flabbergasted to see high school basketball scores in September and October. Schools from exotic-sounding places such as Jumpertown, Hickory Flat, Ingomar, Potts Camp, Wheeler, Baldwyn, Blue Mountain and West Union were already playing basketball. And it seemed as if they played every night. The 1956 Ingomar girls won the state championship and finished with a 54-0 record. Fifty-four and zero!

I remember asking my daddy about it, and his saying, “Those schools don’t play football, son. They don’t have enough students for a football team. They play basketball year-round.”

He showed me on a state map where those towns were and he told me this, too: “Those teams know how to play.”

For five decades now, I’ve watched those teams from tiny towns and communities make the three hours-plus drive down to the Big House, and to this day am still amazed at how many folks follow the yellow school buses to support their favorite team. Blue Mountain is a community of about 800, but there appeared at least 2,000 blue-clad fans yelling themselves hoarse at the championship game.

“We get support from all over Tippah County,” Regina Chills, the Blue Mountain coach, said. “There were people from Ripley and Walnut here cheering for us.”

One strongly suspects there were also Blue Mountain ex-patriots who now live in other parts of Mississippi in attendance as well. Basketball pride and tradition runs deep in Hill Country.

Take Ingomar, which won both the 2A titles. That makes 20 state championships total for Ingomar, 13 for the girls and seven for the boys. This one was particularly special in Ingomar, because Jonathan Ashley, son of Ingomar coaching legend Norris Ashley, won his second as a coach, his first in the Big House. Norris Ashley, whose 1978 team famously won the Overall State Championship (back when there was such a thing), representing the smallest classification. It was Hoosiers in Mississippi.

Norris Ashley, who died just over a year ago, won nine state titles and more than 1,700 games. His son learned from one of the best to ever do it by following his daddy’s teams to the Big House nearly ever year. Norris Ashley was like Hill Country deity. You think this year’s championship wasn’t extra special in Ingomar and in the Ashley family?

Excellent coaching has been the staple of Hill Country basketball. Ashley and others such as brothers Milton and Malcolm Kuykendall, Harvey Childers, Jimmy Guy McDonald, Gerald Caveness, Kermit Davis Sr., and, let us not forget, Baldwyn legend Babe McCarthy easily would have won elections for mayor in their towns. But then, why take a demotion?

The next generation of Hill Country coaches — folks such as Jonathan Ashley and Trent Adair at Ingomar, Cliff Little at Biggersville, and Mike Smith at Booneville — carry on the tradition.

As Rickey Neaves put it, “Those coaches, in many cases, are the most respected people in their communities. You rarely see them leave. Why would they? The communities support them so well. The gyms are packed. The kids grow up wanting to play. That’s why good coaches gravitate to that area and stay there. Who wouldn’t want to coach basketball where basketball is so important?”

Who, indeed?

MHSAA State Championship results

Class 7A: Boys: Meridian 54, Clinton 50; Girls: Tupelo 47, Germantown 38

Class 6A: Boys: Olive Branch 59, Ridgeland 56; Girls; Neshoba Central 53, Terry 39

Class 5A: Boys: Canton 58, Yazoo City 40; Girls: Laurel 40, Canton 32

Class 4A: Boys: Raymond 53, McComb 28; Girls: Tishomingo County 37, Morton 17

Class 3A: Boys: Booneville 46, Coahoma County 43 (OT); Girls: Belmont 40, Booneville 39

Class 2A: Boys: Ingomar 48, Bogue Chitto 46; Ingomar 57, New Site 40

Class 1A: Boys: Biggersville 45, McAdams 41; Girls: Blue Mountain 38, Lumberton 36

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

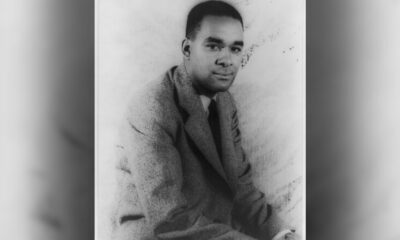

On this day in 1945, Richard Wright’s memoir was top-selling book in U.S.

April 29, 1945

“Black Boy,” Richard Wright’s memoir about his upbringing in Roxie, Mississippi, became the top-selling book in the U.S.

Wright described Roxie as “swarming with rats, cats, dogs, fortune tellers, cripples, blind men, whores, salesmen, rent collectors, and children.”

In his home, he looked to his mother: “My mother’s suffering grew into a symbol in my mind, gathering to itself all the poverty, the ignorance, the helplessness; the painful, baffling, hunger-ridden days and hours; the restless moving, the futile seeking, the uncertainty, the fear, the dread; the meaningless pain and the endless suffering. Her life set the emotional tone of my life.”

When he was alone, he wrote, “I would hurl words into this darkness and wait for an echo, and if an echo sounded, no matter how faintly, I would send other words to tell, to march, to fight, to create a sense of the hunger for life that gnaws in us all.”

Reading became his refuge.

“Whenever my environment had failed to support or nourish me, I had clutched at books,” he wrote. “Reading was like a drug, a dope. The novels created moods in which I lived for days.”

In the end, he discovered that “if you possess enough courage to speak out what you are, you will find you are not alone.” He was the first Black author to see his work sold through the Book-of-a-Month Club.

Wright’s novel, “Native Son,” told the story of Bigger Thomas, a 20-year-old Black man whose bleak life leads him to kill. Through the book, Wright sought to expose the racism he saw: “I was guided by but one criterion: to tell the truth as I saw it and felt it. I swore to myself that if I ever wrote another book, no one would weep over it; that it would be so hard and deep that they would have to face it without the consolation of tears.”

The novel, which sold more than 250,000 copies in its first three weeks, was turned into a play on Broadway, directed by Orson Welles. He became friends with other writers, including Ralph Ellison in Harlem and Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus in Paris. His works played a role in changing white Americans’ views on race.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

The post On this day in 1945, Richard Wright's memoir was top-selling book in U.S. appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

This article focuses on the historical context of Richard Wright’s memoir, “Black Boy,” and its impact on American literature and race relations. It presents facts about Wright’s life and work without taking an overt political stance. The tone is primarily reflective and factual, detailing Wright’s literary achievements and his contributions to addressing racial issues in America. The language is neutral and descriptive, with no evident bias toward either side of the political spectrum. It does not push a specific ideological agenda but instead highlights historical and literary significance.

Mississippi Today

Trump appoints former Gov. Phil Bryant to FEMA Review Council as state awaits ruling on tornadoes

President Donald Trump has appointed former Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant to the FEMA Review Council, which Trump has tasked to “fix a terribly broken system” and shift disaster response and recovery from federal to state government.

The appointment comes as Mississippi awaits a response from the Trump administration on whether it will approve Gov. Tate Reeves’ request for a federal disaster declaration for deadly tornadoes in mid-March. The federal declaration, which Reeves requested April 1, would allow families and local governments devastated by the storms to receive federal assistance. Trump recently denied a similar request for Arkansas.

Trump has said states should shoulder more of the burden for disaster response and recovery, and he and Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem have threatened to shut down the Federal Emergency Management Agency altogether.

“I am proud to announce the formation of the FEMA Review Council, comprised of Top Experts in their fields, who are Highly Respected by their peers,” Trump wrote on social media. “… I know that the new Members will work hard to fix a terribly broken System, and return power to State Emergency Managers, who will help, MAKE AMERICA SAFE AGAIN.”

Trump listed other members of the council, including Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth and Govs. Greg Abbott of Texas and Glenn Youngkin of Virginia.

Bryant, a longtime political ally of Trump, on social media wrote he is, “Honored to receive this appointment …” and that “Unfortunately, we’ve earned a lot of experience with natural disasters and recovery in Mississippi. Let’s Make America Safe Again.”

Mississippi saw seven deaths and an estimated $18 million in destruction from multiple tornadoes on March 14-15, the same storm system that caused damage in Arkansas. The Mississippi Emergency Management Agency reported that 233 homes were destroyed across 14 counties, and hundreds more were damaged.

During the initial aftermath, Reeves told reporters he believed there was a “high likelihood” the state’s damages from the March tornadoes would meet the threshold for FEMA’s Individual Assistance, which provides direct payments to disaster victims.

The Trump administration’s FEMA has denied federal assistance for flooding in West Virginia, tornadoes in Arkansas and a storm in Washington state, and refused North Carolina’s request for extending relief after Hurricane Helene.

After Hurricane Katrina’s devastation in 2005, Mississippi received nearly $25 billion in federal relief spending, which state leaders have credited with saving the state from ruin and allowing communities and families to rebuild.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Right

The content presents a fairly neutral tone but leans towards a center-right perspective, particularly in its framing of President Trump’s actions and the appointment of former Mississippi Governor Phil Bryant. It highlights the argument for more state-level responsibility in disaster management, a position typically associated with conservative views. The reference to the Trump administration’s denial of federal assistance to certain states, including Arkansas, aligns with a more fiscally conservative stance that prioritizes reducing federal intervention. However, the mention of the substantial federal aid Mississippi received after Hurricane Katrina adds a historical balance to the perspective, indicating that the piece does not fully align with extreme conservative views.

Mississippi Today

Chris Lemonis fired, national search underway for Mississippi State baseball

Not quite four years after guiding Mississippi State to a baseball national championship, head coach Chis Lemonis has been fired, effective immediately.

Assistant coach Justin Parker will serve as interim head coach for the remainder of the season.

Mississippi State made the announcement in a press release Monday afternoon.

“A change in leadership is what is best for the future of Mississippi State baseball,” State athletic director Zac Selmon said. “We have not consistently met the standard of success that our university, fans and student-athletes expect and deserve. I want to thank Coach Lemonis for his work and the time he gave to our program, including a national championship in 2021. We appreciate his efforts and wish him and his family all the best moving forward.”

A national search is underway to identify the program’s next head coach, Selmon said.

“In a team meeting moments ago, I expressed to our student-athletes the confidence we have in their abilities and the potential they have for the remainder of the season,” Selmon said. “I encouraged them to compete with pride, resilience, and intensity. With the hard work, preparation, and talent already within this group, we are committed to putting them in the best position to finish the season competing at the highest level.

“Mississippi State is the premier job in college baseball. The tradition, the facilities, the NIL offerings and the fan base are all second to none. Dudy Noble Field is the best environment in the sport, period.”

The current Bulldogs have a 25-19 record and are 7-14 in the SEC. Most recently, the Bulldogs lost two of three weekend games to Auburn, the nation’s 11th-ranked team. State has lost its last two SEC series and five of seven this season. The Bulldogs are currently No. 45 in the nation in ratings percentage index (RPI) and are in danger of not making the NCAA Tournament for the third time in four years.

Lemonis’ MSU teams won 232 games and lost 135 in his six-plus seasons. Hired by former MSU baseball coach and athletic director John Cohen from Indiana, Lemonis has an overall coaching record of 373-226-2.

“This program is built for success,” Selmon said. “Our history proves it, and our future demands it. We are one of only four programs in NCAA history to reach the College World Series in six consecutive decades. With 40 NCAA Tournament appearances, 12 trips to Omaha, 11 SEC regular season titles, and a national championship, our program has always been a national contender. That is the bar. We’re going to find a leader who will embrace that, elevate our program and compete for championships.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

The content provided is a straightforward news report about the firing of a baseball coach, Chis Lemonis, following his achievement of winning a national championship. The information is factual and does not indicate any political leaning, ideology, or bias. It is neutral in tone and intent.

-

SuperTalk FM7 days ago

SuperTalk FM7 days agoNew Amazon dock operations facility to bring 1,000 jobs to Marshall County

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed3 days ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed3 days agoMissouri lawmakers on the cusp of legalizing housing discrimination

-

Mississippi Today2 days ago

Mississippi Today2 days agoDerrick Simmons: Monday’s Confederate Memorial Day recognition is awful for Mississippians

-

Mississippi Today5 days ago

Mississippi Today5 days agoStruggling water, sewer systems impose ‘astronomic’ rate hikes

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Georgia News Feed7 days agoOrganization files ethics complaint against Warnock | Georgia

-

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed5 days agoIs West Virginia — and the rest of the country — prepared to care for our seniors?

-

Mississippi Today5 days ago

Mississippi Today5 days agoParents, providers urge use of unspent TANF for child care

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days agoOp-Ed: Another dismal year for ranked-choice voting | Opinion