Mississippi Today

Greenwood Leflore officials hope hospital can remain open through upcoming legislative session

Greenwood Leflore officials hope hospital can remain open through upcoming legislative session

The head of Greenwood Leflore Hospital said the hospital is working with the city, county and members of the business community to secure the funding needed to keep the hospital open through the legislative session.

In the meantime, the hospital has announced it will close the Greenwood Pulmonology Clinic and the Greenwood Primary Care Clinic as of Nov. 30. The hospital has recently laid off as many as 80 employees and shuttered services including its labor and delivery unit.

The 208-bed hospital is currently operating with a total of 18 inpatient beds.

Interim Chief Executive Officer Gary Marchand said the hospital’s long-term hopes hinge on legislative action and gaining federal Critical Access or Rural Emergency Hospital status. Hospitals with these designations receive enhanced federal payments for certain services among other benefits.

“The legislature will have the opportunity to address a proposed increase in hospital funding for Medicaid and uninsured patients that will help protect the hospital’s cost structure,” Marchand wrote in a memo to employees Thursday.

Though Marchand declined to specify what proposal he was referring to, Richard Roberson of the Mississippi Hospital Association said he was likely referring to an item on the Mississippi Hospital Association’s legislative agenda: additional funding from Medicaid to hospitals.

Hospitals in Mississippi currently receive payments beyond the base rate for Medicaid called “supplemental payments.” These include disproportionate share payments intended to offset hospitals’ uncompensated care costs and improve access for Medicaid and uninsured patients as well as protect hospitals’ finances.

Roberson, the association’s vice president for policy and state advocacy, was not able to provide further details on the amount and type of supplemental funding being proposed on Thursday.

In the meantime, the hospital is working with the city, county and business community to shore up funding.

The move comes after months of negotiations with the University of Mississippi Medical Center ended abruptly earlier this month. Hospital officials said at the time that without an agreement with UMMC to lease the hospital, it could close before the end of the year.

Dr. Alan Jones, associate vice chancellor for clinical affairs at UMMC, said the agreement was not possible due to several factors, the primary one being “the current realities of health care economics that all health systems are facing in this challenging environment.”

This year is on track to be the worst financial year for health care systems nationally – driven mainly by the labor shortage and the increased costs of employing expensive contract nurses.

UMMC reported a more than $8 million loss in its first quarter of this fiscal year, according to a presentation made by its Chief Financial Officer Nelson Weichold.

More than half of Mississippi’s rural hospitals are at risk of closure, new data from the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform shows. The state has the largest number of rural hospitals at immediate risk of closure in the nation at 24.

Editor’s note: Kate Royals, Mississippi Today’s community health editor since January 2022, worked as a writer/editor for UMMC’s Office of Communications from November 2018 through August 2020, writing press releases and features about the medical center’s schools of dentistry and nursing.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

A self-proclaimed ‘loose electron’ journeys through Jackson’s political class

The day after Tim Henderson finished third in Jackson’s mayoral primary, garnering 3,499 votes, the retired Air Force lieutenant colonel was planning to pack up his office at the Jackson Medical Mall and be out by the end of the week.

Henderson figured that’s what losing candidates do. Then he said his older brother gave him a different perspective: Henderson had just established a base of people who had rejected the city’s status quo, and he shouldn’t let them down.

“That’s what happens all the time,” Henderson said. “Candidates show up, they don’t win, the stuff they talked about doing, they walk away, and they leave the people hanging, which is partly, probably why people have lost faith in the process.”

As the 54-year-old space industry consultant spoke with friends, family and politicos last week, he began to look at those 3,499 votes differently. Instead of an outright loss, the numbers seemed to represent something remarkable: In a city where name recognition is king, it took less than a year for Henderson to go from a name few knew to finishing just 786 votes shy of the incumbent, Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba.

He did it with a handful of volunteers and few connections to the city’s powerbrokers or politically connected church leaders or nonprofits. In fact, Henderson thinks his relatively little clout is precisely why he did so well.

“People insulate themselves inside of certain circles, and the problem a lot of people have with Henderson is I wasn’t connected or associated with any of those cliques,” he said. “People immediately started asking, who knows him?”

Now, Henderson is contemplating what he’s going to do next.

“I can be the mayor of the city hall, or I can be the mayor out here on the streets,” he said.

Beholden mainly to God and the truth, he said, he’s ready to talk – with little filter – about what Jackson needs to anyone who wants to listen. He described himself as “a loose neutron, or a loose electron, free radical.”

“Not radical in the sense of ‘radical’ but somebody that doesn’t have to be guarded in how I do things,” he said, adding, “Now I can say things other people can’t say and I can represent things the right way.”

He’s not sure he’ll endorse anyone. Henderson said that in the past week, he’s met with the Lumumba campaign, as well as state Sen. John Horhn, whose 12,359 votes nearly preempted a runoff. To win the Democratic nomination outright, Horhn would have had to secure around 500 of the votes Henderson or 10 other candidates received.

Both asked what their campaigns needed to do to get Henderson’s support. He says he told them the same thing: Start an Office of Ethics and Accountability, one of his chief campaign goals.

He wouldn’t say which candidate said what. But one told him they weren’t sure the city had the funding for it. He recalled the other asked if Henderson would work with them if they started an Office of Integrity, to which Henderson responded “only by my rules.”

Through a spokesperson, Horhn said he wants to bring more accountability to the city’s procurement process and that his ongoing discussions with Henderson have been “productive.”

Horhn has been a senator representing parts of Jackson since the 1990s, and Lumumba is finishing his second term as mayor. If nothing has changed in the city in the last eight, or 32, years, Henderson reasons that’s because the people with power and connections, including those behind the scenes, don’t want change.

When Henderson moved back to the city two years ago, the Cleveland, Miss. native and Mississippi Valley State University graduate moved in with his brother, who lives in south Jackson.

The retired military man had two goals in mind: Develop the vacant lots he owns near the Westside Community Center — a neighborhood called “the Sub” — and start a gourmet grocery store in downtown Jackson, hopefully on the first floor of the Lamar Life building owned by longtime downtown Jackson developer Andrew Mattiace.

Henderson said he couldn’t find the funding – a common refrain in Jackson – or secure meetings with folks who might provide the funding. Still, his business endeavors bore political fruit as he met people he said encouraged him to run for mayor. That included Robert Gibbs, an attorney and developer who was working to convene a group of community and business leaders to secure a new city leader. The coalition assumed the name Rethink Jackson.

Last year, Gibbs invited Henderson to meet with Rethink Jackson members and others at the Capital Club, a highrise bar owned by Mattiace. The group was looking for a candidate to support, but Henderson recalled that Gibbs told him the meeting was not “an endorsement.”

But when Henderson arrived, he says they kept him waiting in the lobby for 30 minutes before finally calling him up to meet with the dozen or so people in the room – mostly African American leaders – who were sitting at tables around the bar.

Gibbs was there, so were Mattiace and Jeff Good, a local restauranteur.

“Before we move forward, I want to make sure the air is clear: This is not an endorsement,” Henderson recalled telling the room. “And they’re like no, nope, it’s not an endorsement. I say well let me be clear you may not hear what you want to hear this evening. I’m only going to share what I’m comfortable sharing, because what I’m not going to do is have my information travel all across the city. Is that fair? That is fair, right? OK, so let’s talk.”

When the group asked about economic development, Henderson said he brought up the Capitol Police, saying “I don’t care how much police security you put down here, you gotta put something in the parts of the city where people live,” meaning both safety and opportunity in west and south Jackson.

“They can only rob other poor people so much,” Henderson said, to which he recalled the folks in the room “just looked at me.”

Mattiace said he preferred not to comment on the election so he could remain neutral for the sake of his business. Good said he did not have a good memory of the meeting but added he thinks Henderson is a “good guy” and that’s why he did well at the polls.

Gibbs didn’t comment on the meeting but said he’s heavily involved in the Horhn campaign and doesn’t want to hurt it. He did speak to Rethink Jackson as a coalition, adding that the group also met with Horhn, Delano Funches, and Rodney DePriest, an independent, “to identify the person we felt would be the best person to lead the city of Jackson.”

After meeting with him, Henderson said he told one of the folks that he wouldn’t be back – he had a campaign to run. He didn’t hear from the group again.

Rethink Jackson debated and took a vote on which candidates “could come in on day one and start doing the things we felt the city needed in order to turn around,” Gibbs said.

“We had a vote, paper ballot voting, that we took so that people could not necessarily be influenced by someone who was in the room,” he added.

Out of about 50 people, Gibbs said only one person was unsure of Horhn. The endorsement was a campaign score for the senator.

It wasn’t just the business community Henderson says did not ultimately align with his campaign. When he talks about the status quo he wants to undo, he means nonprofits, too.

On the campaign trail, Henderson committed to personally screening all nonprofits that receive city grant funds. He wanted to send out screening criteria, categorize all the buckets of grant funding the city was dispersing, and meet with each nonprofit. But if they didn’t show up, he said he would contact their other funders.

He called this “a dogwhistle” – a tell that he was on to them.

“You’re using my data,” he said. “As the mayor, it’s my data. And if you’re supposed to be working in this city, I want to know outcomes.”

Jackson has an excess of nonprofits, Henderson said, that are all working to tackle similar social ills, from decreasing homelessness and youth violence to improving mental health. Some are doing good work and should be supported to leverage their resources. But for others, those missions are a “smokescreen,” Henderson said, and the problems remain. Coincidentally, this is a similar campaign pillar of conservative talk radio host and independent mayoral candidate Kim Wade.

“Here’s my concern: Things aren’t getting better because people don’t want them to get better,” Henderson said. “If you keep crime high, poverty high, you keep the education system where it is, you keep housing, the lack of affordable housing high, you keep jobs at the minimum wage – the only thing people have as an entry point, there’s no upward mobility. This city will never be what it can be. … Because if you wanted change, you’d work yourself out of a job.”

Within city hall, Henderson said he wanted to “clear the slate” by rehiring every department head, putting out job descriptions, and hiring candidates with a blind application – no names, race or gender attached – to ensure that a person’s “connections” were not taken into account.

“Those connections over time is why we are the way we are,” he said. “Because the most qualified person is not who you’re hiring. You’re hiring someone connected to you.”

Make no mistake: Henderson made connections, too. He said two names include Shirlene Anderson, a former chief of police under Frank Melton, and Hank Anderson, a retired administrator for IBM who worked in former governor Ray Mabus’s administration. Anderson had approached Henderson after the February debate at Duling Hall and later advised him on how to keep his message straight.

After that, Henderson made a point to answer questions as directly as he could during the candidate forums. He said he stressed: “public safety, cleaning it up, public safety, cleaning it up.”

“Everybody else is talking about economic development and all this other stuff,” he said. “I’m like, either you don’t know what you’re talking about, or you’re playing the people, or it’s both. I’m like no, you can’t get any economic development with crime the way it is.”

But perhaps the most important connection Henderson made during his run for office was with Sherri Jones, the first person to join the campaign and the station manager at WMPR.

The pair formed a kinship over their deep skepticism of the city’s elite — Black and white, activists and church leaders, and especially the politicians and the business owners who seem to be looking out for their bottom line and not for the entire community.

“You got two things you gone have to be aware of,” Jones said. “One is racism. The other is classism. Now, when you deal with the classicism, it’s about a certain group of people and a lot of them are African American and then they are connected with white people and they don’t really care if there’s racism involved or not because they got a certain agenda and it’s gonna always come back and be tied to money.”

From the perspective of the leaders at the Capital Club, the business community wants to help Jackson, so finding a mayor who works with them will result in economic advancement across the city.

Jones saw it differently.

“It’s about contracts, it’s about being in charge of the decision, what’s going to stay open, what’s going to close, how things move,” Jones said.

Nothing will change in Jackson if economic development does not include the entire city, Henderson said. South and west, too.

The primary “wasn’t just about low voter turnout,” he said. “It actually speaks to the psychological impact that the environment and the quality of life has had on people, where they totally felt dejected, rejected and disconnected.”

What he wants most of all is to bring back people’s confidence in Jackson and knows it won’t happen overnight.

“It’s about empowering the people in the city to be able to believe in it again,” Henderson said.

How’s he going to do that? He might start a nonprofit.

Editor’s note: Mississippi Today is moving this summer into the Lamar Life Building, operated by Andrew Mattiace, in downtown Jackson.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Voters can help maintain city of progress in upcoming Jackson election

Editor’s note: This essay is part of Mississippi Today Ideas, a platform for thoughtful Mississippians to share fact-based ideas about our state’s past, present and future. You can read more about the section here.

As Jackson’s mayoral race moves into the April 22 runoff, the future of our city hangs in the balance.

This election is not just about who will sit in City Hall. It is about the direction of our city for years to come. Jackson is at a crossroads, and the choice we make in this runoff will determine whether we continue our journey toward progress or allow the weight of past challenges to slow us down. The outcome of this election will send a message about what kind of city we want to be.

Do we want leadership that is forward-thinking, accountable and committed to real solutions? Or will we settle for leadership that is reactive rather than proactive? The people of Jackson deserve a leader who understands that governance is about service, not status. This is a defining moment. It is a moment that will test our commitment to progress, our ability to persevere and the power of our collective voice.

Our voices will be heard through our vote.

A city of progress

Despite its struggles, Jackson has always been a city of progress. Our history is filled with moments of resilience, innovation and growth. From the Civil Rights movement to economic revitalization efforts, Jacksonians have always been visionaries who believe in creating a better tomorrow. Even in the face of difficulties, our people continue to push forward.

Over the past few years, we have seen improvements in economic development, in efforts to enhance infrastructure and in a growing emphasis on education and community engagement. But we cannot afford to be complacent. Progress does not happen automatically. Progress requires leadership that listens, adapts, and is willing to make bold decisions for the greater good.

The next mayor of Jackson must not only understand our city’s challenges but be willing to fight for the innovative policies and investments that will strengthen our schools, enhance public safety and expand economic opportunities for all residents. Progress is not just about making promises; it is about taking action.

A city of perseverance

Jackson is no stranger to adversity. From economic setbacks to infrastructure failures, our city has endured its fair share of difficulties. We have faced crises with our water system, budget constraints and rising crime rates, but through it all, the people of Jackson have continued to push forward. Perseverance is part of who we are. It is in our DNA.

Our next mayor must embody that same spirit of perseverance. This is not a position for someone who wants the title without the responsibility. It is not a job

for someone looking for an easy win or political gain. We need a leader who understands that real change requires commitment, hard work and the ability to navigate complex challenges with determination and integrity.

Leadership in Jackson requires someone who will not back down when things get tough. We need a mayor who will fight for solutions, not excuses—who will prioritize action over rhetoric. The people of Jackson deserve leadership that is as resilient as they are.

A city of power

Jackson’s greatest strength is its people. We are a city of educators, entrepreneurs, activists and students —each playing a vital role in shaping our community. Our collective voice has the power to drive change and that power must be reflected in the leadership we choose.

The power of Jackson lies in its communities. From West Jackson to Fondren, from South Jackson to Belhaven, every neighborhood has a voice and a vision for a better city. But for our collective power to be effective, we need leadership that empowers its people. The next mayor of Jackson must be someone who recognizes the importance of investing in our communities, supporting local businesses and uplifting young people who are the future of this city.

This election is an opportunity for Jacksonians to demand bold, transformative leadership. We need someone who is ready to challenge outdated systems, push for new economic opportunities and build a city that is safe, inclusive and thriving.

Our power is in our vote, our voices and our vision for what Jackson can and should be. But power is only meaningful if we use it. If we want to see change, we must show up to the polls on April 22 and make our voices heard.

The choice before us

As we head to the polls, we must ask ourselves some critical questions:

- Who has the vision to lead Jackson into a new era of progress?

- Who has the perseverance to take on our toughest challenges and see them through?

- Who has the power—and the will—to bring our city together and create meaningful change?

These questions are not just theoretical. They will define the future of Jackson. This is not just another election; it is a pivotal moment for our city. The choice we make will impact our schools, our economy, our infrastructure and the safety of our neighborhoods.

We owe it to ourselves, our families and future generations to make the right decision. This is our city, and it is up to us to ensure that it thrives. Leadership matters. Policies matter. And most importantly, our participation in this election matters.

Conclusion

Jackson is a city of progress. A city of perseverance. A city of power. But to fully realize our potential, we need leadership that is committed to action, not just words. The April 22 runoff is our chance to shape the future of Jackson for the better.

Our best days are still ahead—but only if we make the right choice at the ballot box. The power is in our hands. Let’s use it.

Javion Shed is the senior class vice president of Murrah High School, the 2nd Battalion JROTC command sergeant major and a Youth Leadership Greater Jackson member. He is committed to creating a stronger future for the city. He believes participating in the democratic process by voting is essential to the future of Jackson.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

On this day in 1968, Lyndon Johnson signed Civil Rights Act

April 11, 1968

A week after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1968, which paved the way for federal prosecution if someone “willingly injures, intimidates or interferes with another person, or attempts to do so, by force because of the other person’s race, color, religion or national origin” because that person was attending school, patronizing a public place, applying for a job, acting as a juror or voting.

The new law granted Native Americans full access to the rights established in the U.S. Constitution. It also included the Fair Housing Act, which barred racial discrimination in the sale, rental or leasing of U.S. housing in the wake of housing protests in Chicago and elsewhere.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

-

The Center Square7 days ago

The Center Square7 days agoCA fails audit of federal programs, 66% of COVID unemployment benefits in question | California

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago‘Hands Off!’ Protest Held in Huntsville Saturday | April 5, 2025 | News 19 @ 9 P.M.

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days agoFlorida student accused of punching deputy in the face

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days agoSouth Florida dad shares update on daughter severely burned in Molotov cocktail attack

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days agoFour people rescued, two taken to hospital after Birmingham apartment fire

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed5 days agoProposal: American military base retailers would exclude 4 hostile nations | North Carolina

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed4 days ago

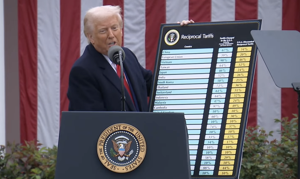

News from the South - Virginia News Feed4 days agoTariffs spark backlash in Virginia over economic impact | Virginia

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days agoTrump fires clean energy leader from TVA board without publicly providing a reason