Certain strains of E. coli can outcompete disease-causing microbes for resources.

Sarguru Subash, Texas A&M University

Millions of people in the U.S. and around the world suffer from urinary tract infections every year. Some groups are especially prone to chronic UTIs, including women, older adults and some veterans.

These infections are typically treated with antibiotics, but overusing these drugs can make the microbes they target become resistant and reduce the medicines’ effectiveness.

To solve this problem of chronic UTIs and antibiotic resistance, we combined our expertise in microbiology and engineering to create a living material that houses a specific strain of beneficial E. coli. Our research shows that the “good” bacteria released from this biomaterial can compete with “bad” bacteria for nutrients and win, dramatically reducing the number of disease-causing microbes.

With further development, we believe this technique could help manage recurring UTIs that do not respond to antibiotics.

Bringing bacteria to the bladder

For the microbes living in people, nutrients are limited their presence varies between different parts of the body. Bacteria have to compete with other microbes and the host to acquire essential nutrients. By taking up available nutrients, beneficial bacteria can stop or slow the growth of harmful bacteria. When harmful bacteria are starved of important nutrients, they aren’t able to reach high enough numbers to cause disease.

Delivering beneficial bacteria to the bladder to prevent UTIs in challenging, though. For one, these helpful bacteria can naturally colonize only in people who are unable to fully empty their bladder, a condition called urinary retention. Even among these patients, how long these bacteria can colonize their bladders varies widely.

Current methods to deliver bacteria to the bladder are invasive and require repeated catheter insertion. Even when bacteria are successfully released into the bladder, urine will flush out these microbes because they cannot stick to the bladder wall.

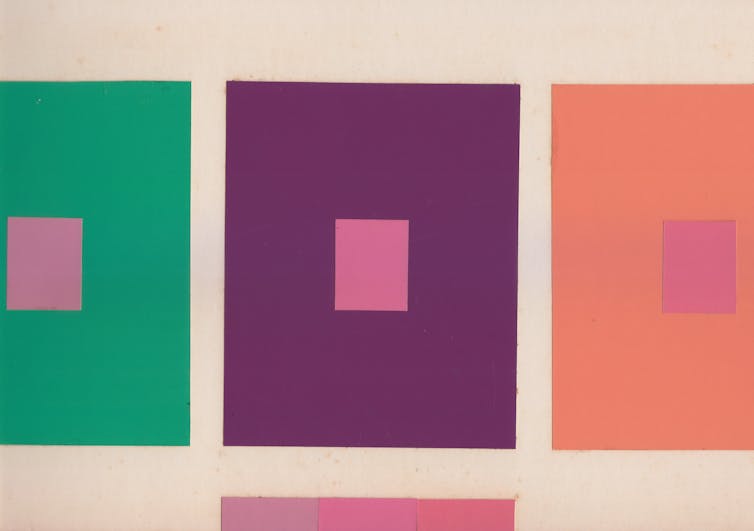

This microscopy image shows the bladder of a mouse (blue) covered with E. coli (pink) and the white blood cells (yellow) attacking them. Valerie O’Brien, Matthew Joens, Scott J. Hultgren, James A.J. Fitzpatrick, Washington University, St. Louis/NIH via Flickr, CC BY-NC

Biomaterials to treat UTIs

Since beneficial bacteria cannot attach to and survive in the bladder for long, we developed a biomaterial that could slowly release bacteria in the bladder over time.

Our biomaterial is composed of living E. coli embedded in a matrix structure made of gel. It resembles a piece of jelly about 500 times smaller than a drop of water and can release bacteria for up to two weeks in the bladder. By delivering the bacteria via biomaterial, we overcome the need for the bacteria to attach to the bladder to persist in the organ.

We tested our biomaterial by placing it in human urine in petri dishes and exposing it to bacterial pathogens that cause UTIs. Our results showed that when mixed in a 50:50 ratio, the E. coli outcompeted the UTI-causing bacteria by increasing to around 85% of the total population. When we added more E. coli than UTI-causing bacteria, which is what we envision for future development and testing, the proportion of E. coli increased to over 99% of the population, essentially wiping out the UTI-causing bacteria. Moreoever, the biomaterial continued releasing E. coli for up to two weeks in human urine.

Our findings suggest that E.coli could stick around and survive in the bladder for extended periods of time and successfully decrease the growth of many types of bacteria that cause UTIs.

Improving biomaterials

Our findings show that E. coli can not only control harmful bacteria it’s closely related to but also a broad range of disease-causing bacteria in humans and animals. This means scientists might not need to identify different types of beneficial bacteria to control each pathogen – and there are many – that can cause a UTI.

Our team is currently evaluating how effectively our biomaterial can cure UTIs in mice. We are also working to identify the specific nutrients that beneficial and harmful bacteria compete over and what factors may help beneficial bacteria win. We could add these nutrients to our biomaterial to be released or withheld.

This research is still at an early stage, and clinical uses are not in development yet, so if it does reach patients it will be well in the future. We hope that our technology could be refined and applied to control other bacterial infections and some cancers caused by bacteria.![]()

Sarguru Subash, Assistant Professor of Veterinary Pathobiology, Texas A&M University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.