Nneka Vivian Iduu, Auburn University

In the 20th century, when a routine infection was treated with a standard antibiotic, recovery was expected. But over time, the microbes responsible for these infections have evolved to evade the very drugs designed to eliminate them.

Each year, there are more than 2.8 million antibiotic-resistant infections in the United States, leading to over 35,000 deaths and US$4.6 billion in health care costs. As antibiotics become less effective, antimicrobial resistance poses an increasing threat to public health.

Antimicrobial resistance began to emerge as a serious threat in the 1940s with the rise of penicillin resistance. By the 1990s, it had escalated into a global concern. Decades later, critical questions still remain: How does antimicrobial resistance emerge, and how can scientists track the hidden changes leading to it? Why does resistance in some microbes remain undetected until an outbreak occurs? Filling these knowledge gaps is crucial to preventing future outbreaks, improving treatment outcomes and saving lives.

Over the years, my work as a microbiologist and biomedical scientist has focused on investigating the genetics of infectious microbes. My colleagues and I identified a resistance gene previously undetected in the U.S. using genetic and computational methods that can help improve how scientists detect and track antimicrobial resistance.

Challenges of detecting resistance

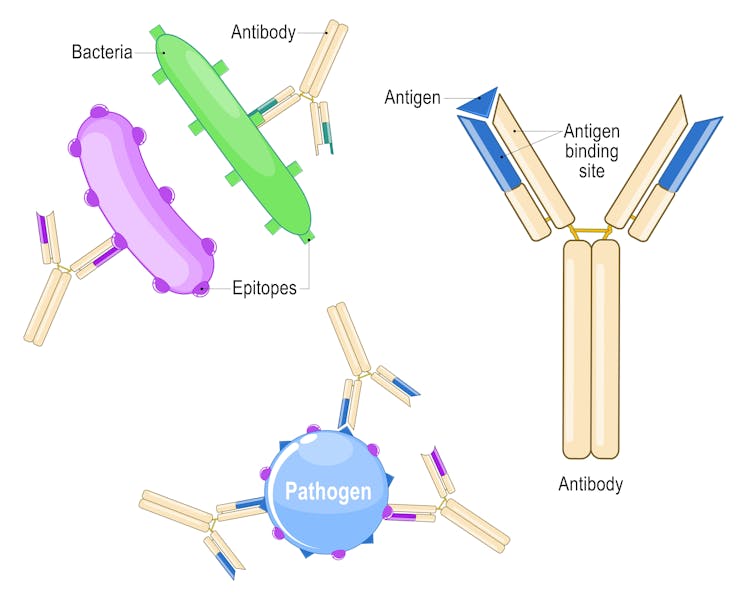

Antimicrobial resistance is a natural process where microbes constantly evolve as a defense mechanism, acquiring genetic changes that enhance their survival.

Unfortunately, human activities can speed up this process. The overuse and misuse of antibiotics in health care, farming and the environment push bacteria to genetically change in ways that allow them to survive the drugs meant to kill them.

Early detection of antimicrobial resistance is crucial for effective treatment. Surveillance typically begins with a laboratory sample obtained from patients with suspected infections, which is then analyzed to identify potential antimicrobial resistance. Traditionally, this has been done using culture-based methods that involve exposing microbes to antibiotics in the lab and observing whether they survived to determine whether they were becoming resistant. Along with helping authorities and researchers monitor the spread of antimicrobial resistance, hospitals use this approach to decide on treatment plans.

However, culture-based approaches have some limitations. Resistant infections often go unnoticed until antibiotics fail, making both detection and intervention processes slow. Additionally, new resistance genes may escape detection altogether.

Genomics of antimicrobial resistance

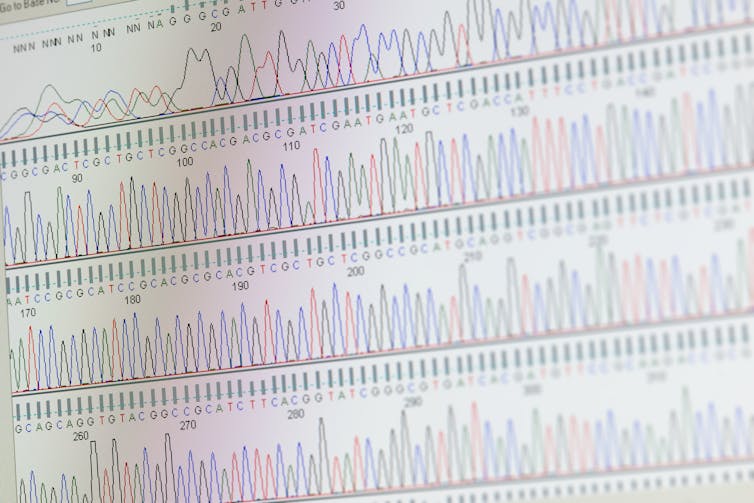

To overcome these challenges, researchers have integrated genomic sequencing into antimicrobial resistance surveillance. Through whole-genome sequencing, we can analyze all the DNA in a microbial sample to get a comprehensive view of all the genes present – including those responsible for resistance. With the computational tools of bioinformatics, researchers can efficiently process vast amounts of genetic data to improve the detection of resistance threats.

Despite its advantages, integrating genomic sequencing into antimicrobial resistance monitoring presents some challenges of its own. High costs, quality assurance and a shortage of trained bioinformaticians make implementation difficult. Additionally, the complexity of interpreting genomic data may limit its use in clinical and public health decision-making.

hh5800/iStock via Getty Images Plus

Establishing international standards could help make whole-genome sequencing and bioinformatics a fully reliable tool for resistance surveillance. The World Health Organization recommends laboratories follow strict quality control measures to ensure accurate and comparable results. This includes using reliable, user-friendly computational tools and shared microbial databases. Additional strategies include investing in training programs and fostering collaborations between hospitals, research labs and universities.

Discovering a resistance gene

Combining whole genome sequencing and bioinformatics, my colleagues and I analyzed Salmonella samples collected from several animal species between 1982 and 1999. We discovered a Salmonella resistance gene called blaSCO-1 that has evaded detection in U.S. livestock for decades.

The blaSCO-1 gene confers resistance to microbes against several critical antibiotics, including ampicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and, to some extent, cephalosporins and carbapenems. These medications are crucial for treating infections in both humans and animals.

NIAID/Flickr, CC BY-SA

The blaSCO-1 gene likely remained unreported because routine surveillance usually targets well-known resistance genes and it has overlapping functions with other genes. Gaps in bioinformatics expertise may have also hindered its identification.

The failure to detect genes like blaSCO-1 raises concern about its potential role in past treatment failures. Between 2015 and 2018, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention began implementing whole-genome sequencing for routine surveillance of Salmonella. Studies conducted during this period found that 77% of multistate outbreaks were linked to livestock harboring resistant Salmonella.

These missed genes have significant implications for both food safety and public health. Undetected antimicrobial resistance genes can spread through food animals, contaminated food products, processing environments and agricultural runoff, allowing resistant bacteria to persist and reach humans. These resistant bacteria lead to infections that are harder to treat and increase the risk of outbreaks. Moreover, the global movement of people, livestock and goods means that these resistant strains can easily cross borders, turning local outbreaks into worldwide health threats.

Identifying new resistance genes not only fills a critical knowledge gap, but it also demonstrates how genomic and computational approaches can help detect hidden resistance mechanisms before they pose widespread threats.

Strengthening surveillance

As antimicrobial resistance continues to rise, adopting a One Health approach that integrates human, animal and environmental factors can help ensure that emerging resistance does not outpace humans’ ability to combat it.

Initiatives like the Quadripartite AMR Multi-Partner Trust Fund provide support for programs that strengthen global collaborative surveillance, promote responsible antimicrobial use and drive the development of sustainable alternatives. Ensuring researchers around the world follow common research standards will allow more labs – especially those in low- and middle-income countries – to contribute to global surveillance efforts.

The health of future generations depends on the world’s ability to ensure food safety and protect public health on a global scale. In the ongoing battle between microbial evolution and human innovation, vigilance and adaptability are key to staying ahead.![]()

Nneka Vivian Iduu, Graduate Research Assistant in Pathobiology, Auburn University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.