AI tools can help doctors synthesize all the information that goes into a clinical decision.

Aaron J. Masino, Clemson University

The practice of medicine has undergone an incredible, albeit incomplete, transformation over the past 50 years, moving steadily from a field informed primarily by expert opinion and the anecdotal experience of individual clinicians toward a formal scientific discipline.

The advent of evidence-based medicine meant clinicians identified the most effective treatment options for their patients based on quality evaluations of the latest research. Now, precision medicine is enabling providers to use a patient’s individual genetic, environmental and clinical information to further personalize their care.

The potential benefits of precision medicine also come with new challenges. Importantly, the amount and complexity of data available for each patient is rapidly increasing. How will clinicians figure out which data is useful for a particular patient? What is the most effective way to interpret the data in order to select the best treatment?

These are precisely the challenges that computer scientists like me are working to address. Collaborating with experts in genetics, medicine and environmental science, my colleagues and I develop computer-based systems, often using artificial intelligence, to help clinicians integrate a wide range of complex patient data to make the best care decisions.

The rise of evidence-based medicine

As recently as the 1970s, clinical decisions were primarily based on expert opinion, anecdotal experience and theories of disease mechanisms that were frequently unsupported by empirical research. Around that time, a few pioneering researchers argued that clinical decision-making should be grounded in the best available evidence. By the 1990s, the term evidence-based medicine was introduced to describe the discipline of integrating research with clinical expertise when making decisions about patient care.

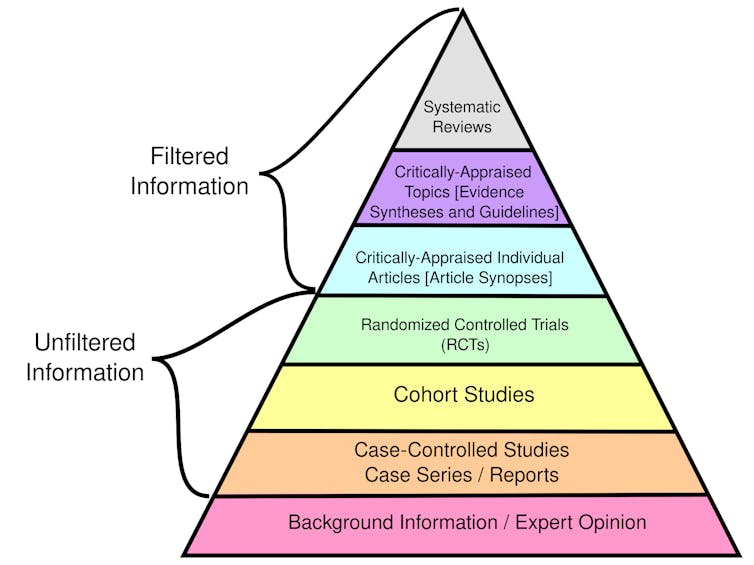

The bedrock of evidence-based medicine is a hierarchy of evidence quality that determines what kinds of information clinicians should rely on most heavily to make treatment decisions.

Certain types of evidence are stronger than others. While filtered information has been evaluated for rigor and quality, unfiltered information has not.

Randomized controlled trials randomly place participants in different groups that receive either an experimental treatment or a placebo. These studies, also called clinical trials, are considered the best individual sources of evidence because they allow researchers to compare treatment effectiveness with minimal bias by ensuring the groups are similar.

Observational studies, such as cohort and case-control studies, focus on the health outcomes of a group of participants without any intervention from the researchers. While used in evidence-based medicine, these studies are considered weaker than clinical trials because they don’t control for potential confounding factors and biases.

Overall, systematic reviews that synthesize the findings of multiple research studies offer the highest quality evidence. In contrast, single-case reports detailing one individual’s experience are weak evidence because they may not apply to a wider population. Similarly, personal testimonials and expert opinions alone are not supported by empirical data.

In practice, clinicians can use the framework of evidence-based medicine to formulate a specific clinical question about their patient that can be clearly answered by reviewing the best available research. For example, a clinician might ask whether statins would be more effective than diet and exercise to lower LDL cholesterol for a 50 year-old male with no other risk factors. Integrating evidence, patient preferences and their own expertise, they can develop diagnoses and treatment plans.

As may be expected, gathering and putting all the evidence together can be a laborious process. Consequently, clinicians and patients commonly rely on clinical guidelines developed by third parties such as the American Medical Association, the National Institutes of Health and the World Health Organization. These guidelines provide recommendations and standards of care based on systematic and thorough assessment of available research.

Dawn of precision medicine

Around the same time that evidence-based medicine was gaining traction, two other transformative developments in science and health care were underway. These advances would lead to the emergence of precision medicine, which uses patient-specific information to tailor health care decisions to each person.

The first was the Human Genome Project, which officially began in 1990 and was completed in 2003. It sought to create a reference map of human DNA, or the genetic information cells use to function and survive.

This map of the human genome enabled scientists to discover genes linked to thousands of rare diseases, understand why people respond differently to the same drug, and identify mutations in tumors that can be targeted with specific treatments. Increasingly, clinicians are analyzing a patient’s DNA to identify genetic variations that inform their care.

Output from the DNA sequencer used by the Human Genome Project.

The second was the development of electronic medical records to store patient medical history. Although researchers had been conducting pilot studies of digital records for several years, the development of industry standards for electronic medical records began only in the late 1980s. Adoption did not become widespread until after the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

Electronic medical records enable scientists to conduct large-scale studies of the associations between genetic variants and observable traits that inform precision medicine. By storing data in an organized digital format, researchers can also use these patient records to train AI models for use in medical practice.

More data, more AI, more precision

Superficially, the idea of using patient health information to personalize care is not new. For example, the ongoing Framingham Heart Study, which began in 1948, yielded a mathematical model to estimate a patient’s coronary artery disease risk based on their individual health information, rather than the average population risk.

One fundamental difference between efforts to personalize medicine now and prior to the Human Genome Project and electronic medical records, however, is that the mental capacity required to analyze the scale and complexity of individual patient data available today far exceeds that of the human brain. Each person has hundreds of genetic variants, hundreds to thousands of environmental exposures and a clinical history that may include numerous physiological measurements, lab values and imaging results. In my team’s ongoing work, the AI models we’re developing to detect sepsis in infants use dozens of input variables, many of which are updated every hour.

Researchers like me are using AI to develop tools that help clinicians analyze all this data to tailor diagnoses and treatment plans to each individual. For example, some genes can affect how well certain medications work for different patients. While genetic tests can reveal some of these traits, it is not yet feasible to screen every patient due to cost. Instead, AI systems can analyze a patient’s medical history to predict whether genetic testing will be beneficial based on how likely they are to be prescribed a medication known to be influenced by genetic factors.

Another example is diagnosing rare diseases, or conditions that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S. Diagnosis is very difficult because many of the several thousand known rare diseases have overlapping symptoms, and the same disease can present differently among different people. AI tools can assist by examining a patient’s unique genetic traits and clinical characteristics to determine which ones likely cause disease. These AI systems may include components that predict whether the patient’s specific genetic variation negatively affects protein function and whether the patient’s symptoms are similar to specific rare diseases.

Future of clinical decision-making

New technologies will soon enable routine measurement of other types of biomolecular data beyond genetics. Wearable health devices can continuously monitor heart rate, blood pressure and other physiological features, producing data that AI tools can use to diagnose disease and personalize treatment.

Related studies are already producing promising results in precision oncology and personalized preventive health. For example, researchers are developing a wearable ultrasound scanner to detect breast cancer, and engineers are developing skinlike sensors to detect changes in tumor size.

Research will continue to expand our knowledge of genetics, the health effects of environmental exposures and how AI works. These developments will significantly alter how clinicians make decisions and provide care over the next 50 years.![]()

Aaron J. Masino, Associate Professor of Computing, Clemson University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.