DrPixel/Moment via Getty Images

Daniel Brady Mills, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich; Jason Wright, Penn State, and Jennifer L. Macalady, Penn State

A popular model of evolution concludes that it was incredibly unlikely for humanity to evolve on Earth, and that extraterrestrial intelligence is vanishingly rare.

But as experts on the entangled history of life and our planet, we propose that the coevolution of life and Earth’s surface environment may have unfolded in a way that makes the evolutionary origin of humanlike intelligence a more foreseeable or expected outcome than generally thought.

The hard-steps model

Some of the greatest evolutionary biologists of the 20th century famously dismissed the prospect of humanlike intelligence beyond Earth.

This view, firmly rooted in biology, independently gained support from physics in 1983 with an influential publication by Brandon Carter, a theoretical physicist.

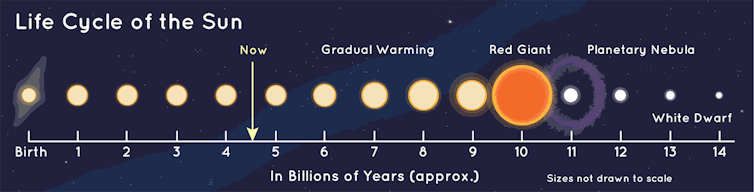

In 1983, Carter attempted to explain what he called a remarkable coincidence: the close approximation between the estimated lifespan of the Sun – 10 billion years – and the time Earth took to produce humans – 5 billion years, rounding up.

Brandon Carter/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

He imagined three possibilities. In one, intelligent life like humans generally arises very quickly on planets, geologically speaking – in perhaps millions of years. In another, it typically arises in about the time it took on Earth. And in the last, he imagined that Earth was lucky – ordinarily it would take much longer, say, trillions of years for such life to form.

Carter rejected the first possibility because life on Earth took so much longer than that. He rejected the second as an unlikely coincidence, since there is no reason the processes that govern the Sun’s lifespan – nuclear fusion – should just happen to have the same timescale as biological evolution.

So Carter landed on the third explanation: that humanlike life generally takes much longer to arise than the time provided by the lifetime of a star.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

To explain why humanlike life took so long to arise, Carter proposed that it must depend on extremely unlikely evolutionary steps, and that the Earth is extraordinarily lucky to have taken them all.

He called these evolutionary steps hard steps, and they had two main criteria. One, the hard steps must be required for human existence – meaning if they had not happened, then humans would not be here. Two, the hard steps must have very low probabilities of occurring in the available time, meaning they usually require timescales approaching 10 billion years.

Do hard steps exist?

The physicists Frank Tipler and John Barrow predicted that hard steps must have happened only once in the history of life – a logic taken from evolutionary biology.

If an evolutionary innovation required for human existence was truly improbable in the available time, then it likely wouldn’t have happened more than once, although it must have happened at least once, since we exist.

For example, the origin of nucleated – or eukaryotic – cells is one of the most popular hard steps scientists have proposed. Since humans are eukaryotes, humanity would not exist if the origin of eukaryotic cells had never happened.

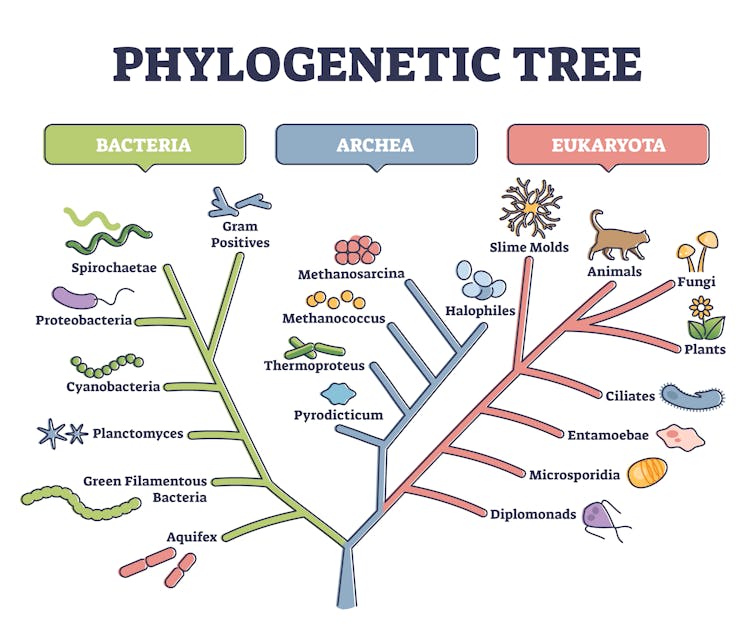

On the universal tree of life, all eukaryotic life falls on exactly one branch. This suggests that eukaryotic cells originated only once, which is consistent with their origin being unlikely.

VectorMine/iStock via Getty Images Plus

The other most popular hard-step candidates – the origin of life, oxygen-producing photosynthesis, multicellular animals and humanlike intelligence – all share the same pattern. They are each constrained to a single branch on the tree of life.

However, as the evolutionary biologist and paleontologist Geerat Vermeij argued, there are other ways to explain why these evolutionary events appear to have happened only once.

This pattern of apparently singular origins could arise from information loss due to extinction and the incompleteness of the fossil record. Perhaps these innovations each evolved more than once, but only one example of each survived to the modern day. Maybe the extinct examples never became fossilized, or paleontologists haven’t recognized them in the fossil record.

Or maybe these innovations did happen only once, but because they could have happened only once. For example, perhaps the first evolutionary lineage to achieve one of these innovations quickly outcompeted other similar organisms from other lineages for resources. Or maybe the first lineage changed the global environment so dramatically that other lineages lost the opportunity to evolve the same innovation. In other words, once the step occurred in one lineage, the chemical or ecological conditions were changed enough that other lineages could not develop in the same way.

If these alternative mechanisms explain the uniqueness of these proposed hard steps, then none of them would actually qualify as hard steps.

But if none of these steps were hard, then why didn’t humanlike intelligence evolve much sooner in the history of life?

Environmental evolution

Geobiologists reconstructing the conditions of the ancient Earth can easily come up with reasons why intelligent life did not evolve sooner in Earth history.

For example, 90% of Earth’s history elapsed before the atmosphere had enough oxygen to support humans. Likewise, up to 50% of Earth’s history elapsed before the atmosphere had enough oxygen to support modern eukaryotic cells.

All of the hard-step candidates have their own environmental requirements. When the Earth formed, these requirements weren’t in place. Instead, they appeared later on, as Earth’s surface environment changed.

We suggest that as the Earth changed physically and chemically over time, its surface conditions allowed for a greater diversity of habitats for life. And these changes operate on geologic timescales – billions of years – explaining why the proposed hard steps evolved when they did, and not much earlier.

In this view, humans originated when they did because the Earth became habitable to humans only relatively recently. Carter had not considered these points in 1983.

Moving forward

But hard steps could still exist. How can scientists test whether they do?

Earth and life scientists could work together to determine when Earth’s surface environment first became supportive of each proposed hard step. Earth scientists could also forecast how much longer Earth will stay habitable for the different kinds of life associated with each proposed hard step – such as humans, animals and eukaryotic cells.

Evolutionary biologists and paleontologists could better constrain how many times each hard-step candidate occurred. If they did occur only once each, they could see whether this came from their innate biological improbability or from environmental factors.

Lastly, astronomers could use data from planets beyond the solar system to figure out how common life-hosting planets are, and how often these planets have hard-step candidates, such as oxygen-producing photosynthesis and intelligent life.

If our view is correct, then the Earth and life have evolved together in a way that is more typical of life-supporting planets – not in the rare and improbable way that the hard-steps model predicts. Humanlike intelligence would then be a more expected outcome of Earth’s evolution, rather than a cosmic fluke.

Researchers from a variety of disciplines, from paleontologists and biologists to astronomers, can work together to learn more about the probability of intelligent life evolving on Earth and elsewhere in the universe.

If the evolution of humanlike life was more probable than the hard-steps model predicts, then researchers are more likely to find evidence for extraterrestrial intelligence in the future.

Daniel Brady Mills, Postdoctoral Fellow in Geomicrobiology, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich; Jason Wright, Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Penn State, and Jennifer L. Macalady, Professor of Geoscience, Penn State

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.