Design Cells/iStock via Getty Images Plus

Sam Pellock, University of Washington

Enzymes are molecular machines that carry out the chemical reactions that sustain all life, an ability that has captured the attention of scientists like me.

Consider muscle movement. Your body releases a molecule called acetylcholine to trigger your muscle cells to contract. If acetylcholine sticks around for too long, it can paralyze your muscles – including your heart muscle cells – and, well, that’s that. This is where the enzyme acetylcholinesterase comes in. This enzyme can break down thousands of acetylcholine molecules per second to ensure muscle contraction is stopped, paralysis avoided and life continued. Without this enzyme, it would take a month for a molecule of acetylcholine to break down on its own – about 10 billion times slower.

You can imagine why enzymes are of particular interest to scientists looking to solve modern problems. What if there were a way to break down plastic, capture carbon dioxide or destroy cancer cells as fast as acetylcholinesterase breaks down acetylcholine? If the world needs to take action quickly, enzymes are a compelling candidate for the job – if only researchers could design them to handle those challenges on demand.

Designing enzymes, unfortunately, is very hard. It’s like working with an atom-sized Lego set, but the instructions were lost and the thing won’t hold together unless it’s assembled perfectly. Newly published research from our team suggests that machine learning can act as the architect on this Lego set, helping scientists build these complex molecular structures accurately.

What’s an enzyme?

Let’s take a closer look at what makes up an enzyme.

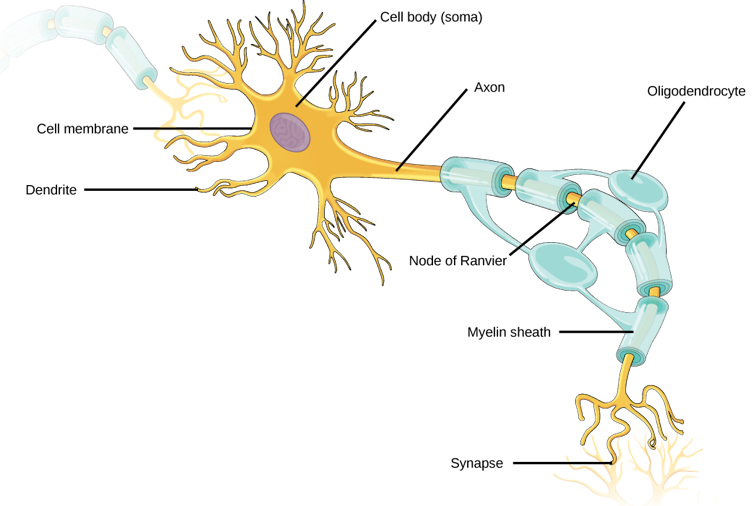

Enzymes are proteins – large molecules that do the behind-the-scenes work that keep all living things alive. These proteins are made up of amino acids, a set of building blocks that can be stitched together to form long strings that get knotted up into specific shapes.

The specific structure of a protein is key to its function in the same way that the shapes of everyday objects are. For example, much like a spoon is designed to hold liquid in a way that a knife simply can’t, the enzymes involved in moving your muscles aren’t well suited for photosynthesis in plants.

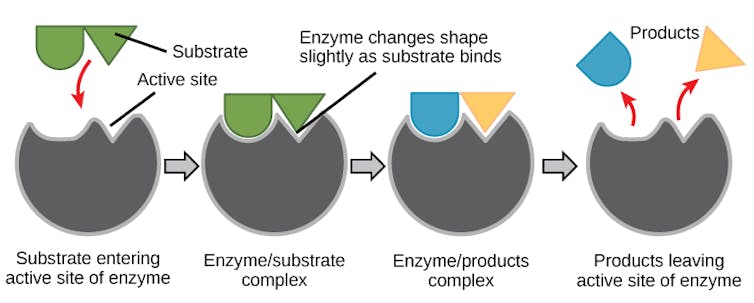

For an enzyme to function, it adopts a shape that perfectly matches the molecule it processes, much like a lock matches a key. The unique grooves in the enzyme – the lock – that interact with the target molecule – the key – are found in a region of the enzyme known as the active site.

OpenStax, CC BY-SA

The active site of the enzyme precisely orients amino acids to interact with the target molecule when it enters. This makes it easier for the molecule to undergo a chemical reaction to turn into a different one, making the process go faster. After the chemical reaction is done, the new molecule is released and the enzyme is ready to process another.

How do you design an enzyme?

Scientists have spent decades trying to design their own enzymes to make new molecules, materials or therapeutics. But making enzymes that look like and go as fast as those found in nature is incredibly difficult.

Enzymes have complex, irregular shapes that are made up of hundreds of amino acids. Each of these building blocks needs to be placed perfectly or else the enzyme will slow down or completely shut off. The difference between a speed racer and slowpoke enzyme can be a distance of less than the width of a single atom.

Initially, scientists focused on modifying the amino acid sequences of existing enzymes to improve their speed or stability. Early successes with this approach primarily improved the stability of enzymes, enabling them to catalyze chemical reactions at a higher range of temperatures. But this approach was less useful for improving the speed of enzymes. To this day, designing new enzymes by modifying individual amino acids is generally not an effective way to improve natural enzymes.

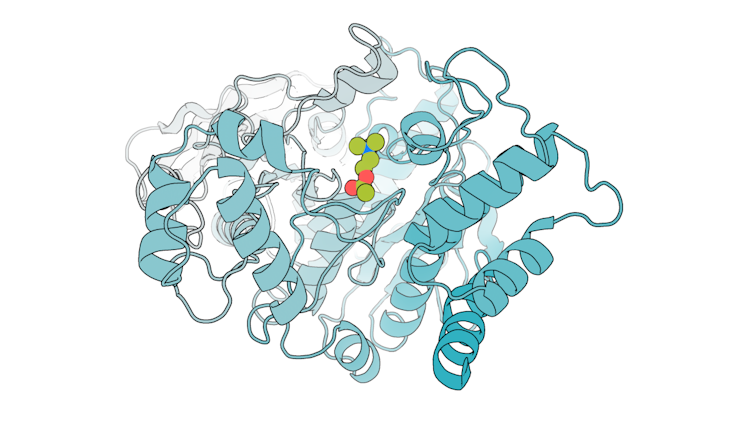

Sam Pellock, CC BY-SA

Researchers found that using a process called directed evolution, in which the amino acid sequence of an enzyme is randomly changed until it can perform a desired function, proved much more fruitful. For example, studies have shown that directed evolution can improve chemical reaction speed, thermostability, and even generate enzymes with properties that aren’t seen in nature. However, this approach is typically labor-intensive: You have to screen many mutants to find one that does what you want. In some cases, if there’s no good enzyme to start from, this method can fail to work at all.

Both of these approaches are limited by their reliance on natural enzymes. That is, restricting your design to the shapes of natural proteins likely limits the kinds of chemistry that enzymes can facilitate. Remember, you can’t eat soup with a knife.

Is it possible to make enzymes from scratch, rather than modify nature’s recipe? Yes, with computers.

Designing enzymes with computers

The first attempts to computationally design enzymes still largely relied on natural enzymes as a starting point, focusing on placing enzyme active sites into natural proteins.

This approach is akin to trying to find a suit at a thrift store: It is unlikely you will find a perfect fit because the geometry of an enzyme’s active site (your body in this analogy) is highly specific, so a random protein with a rigidly fixed structure (a suit with random measurements) is unlikely to perfectly accommodate it. The resulting enzymes from these efforts performed much more slowly than those found in nature, requiring further optimization with directed evolution to reach speeds common among natural enzymes.

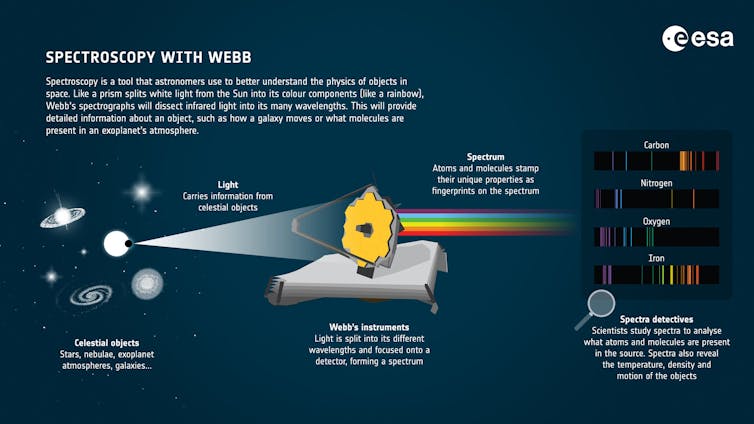

Recent advances in deep learning have dramatically changed the landscape of designing enzymes with computers. Enzymes can now be generated in much the same way that AI models such as ChatGPT and DALL-E generate text or images, and you don’t need to use native protein structures to support your active site.

Our team showed that when we prompt an AI model, called RFdiffusion, with the structure and amino acid sequence of an active site, it can generate the rest of the enzyme structure that would perfectly support it. This is equivalent to prompting ChatGPT to write an entire short story based on a prompt that only says to include the line “And sadly, the eggs never showed up.”

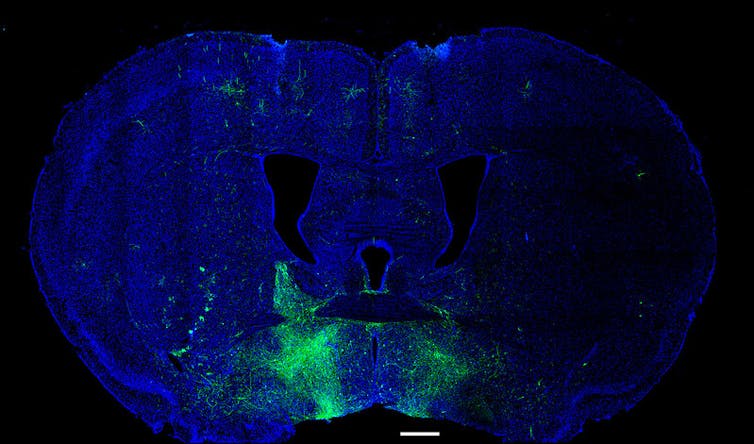

We used this AI model specifically to generate enzymes called serine hydrolases, a group of proteins that have potential applications in medicine and plastic recycling. After designing the enzymes, we mixed them with their intended molecular target to see whether they could catalyze its breakdown. Encouragingly, many of the designs we tested were able to break down the molecule, and better than previously designed enzymes for the same reaction.

To see how accurate our computational designs were, we used a method called X-ray crystallography to determine the shapes of these enzymes. We found that many of them were a nearly perfect match to what we digitally designed.

Our findings mark a key advance in enzyme design, highlighting how AI can help scientists start to tackle complex problems. Machine learning tools could help more researchers access enzyme design and tap into the full potential of enzymes to solve modern-day problems.![]()

Sam Pellock, Postdoctoral Scholar in Biochemistry, University of Washington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.