Visions of America/Joe Sohm/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Francisco I. Pedraza, Arizona State University; Jason L. Morín, California State University, Northridge, and Loren Collingwood, University of New Mexico

One of President Donald Trump’s major promises during the 2024 presidential campaign was to launch mass deportations of immigrants living in the U.S. without legal authorization.

The U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency has said that, since January 2025, it is detaining and planning to deport 600 to 1,100 immigrants a day. That marks an increase from the average 282 immigration arrests that happened each day in September 2024 under the Biden administration.

The current trend would place the Trump administration on track to apprehend 25,000 immigrants in Trump’s first month in office. On an annual basis, this is about 300,000 – far from the “millions and millions” of immigrants Trump promised to deport.

A lack of funding, immigration officers, immigration detention centers and other resources has reportedly impeded the administration’s deportation work.

The Trump administration is seeking US$175 billion from Congress to use for the next four years on immigration enforcement, Axios reported on Feb. 11, 2025.

If Trump does make good on his promise of mass deportations, our research shows that removing millions of immigrants would be costly for everyone in the U.S., including American citizens and businesses.

Andrew Lichtenstein/Corbis via Getty Images

Food costs will increase

One important factor is that mass deportations would weaken key industries in the U.S. that rely on immigrant workers, including those living in the U.S. illegally.

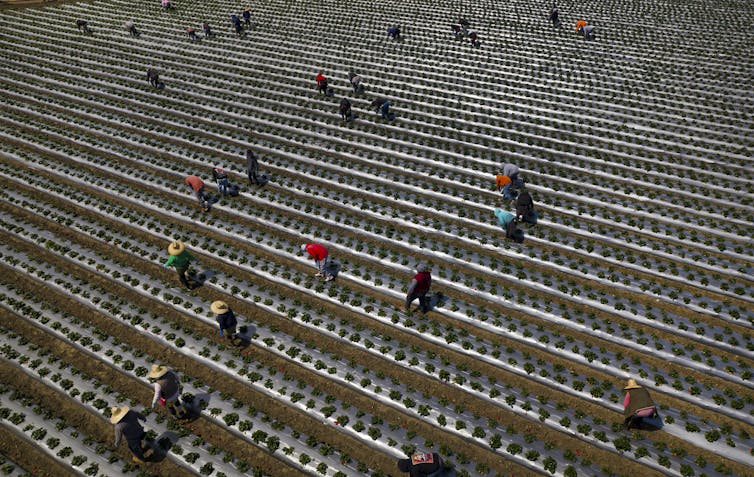

Overall, immigrants without legal authorization make up about 5% of the total U.S. workforce.

But that overall percentage doesn’t reflect these immigrants’ concentrated presence within various industries. Approximately half of U.S. farmworkers are living in the country without legal authorization, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Some of these immigrant farmworkers are skilled supervisors who make decisions about planting and harvesting. Others know how to use and maintain tractors, loaders, diggers, rakers, fertilizer sprayers, irrigation systems, and other machines crucial to farm operations.

If those workers were to be suddenly removed from the country, Americans would see an increase in food costs, including what they spend on groceries and at restaurants.

With fewer available workers to pick fruits and vegetables and prepare the food for shipment and distribution, the domestic production of food could decrease, leading to higher costs and more imports.

National estimates of the restaurant and food preparation workforce, meanwhile, indicate that between 10% and 15% of those workers are immigrants living in the U.S. illegally.

Past state-level immigration enforcement policies offer an idea of what could happen at the national level if Trump were to carry out widespread deportations.

For example, a 2011 Alabama law called HB-56 directed local police officers to investigate the immigration status of drivers stopped for speeding. It also prohibited landlords from renting properties to immigrants who do not have legal authorization to work or live in the country. That law and its resulting effects prompted some Alabama-based immigrant workers to leave the state following workplace raids.

Their departure wound up costing the state an estimated $2.3 billion to $10.8 billion loss in Alabama’s annual gross domestic product due to the loss of workers and economic output.

Other industries that rely on immigrants

Part of the challenge of mass deportations for industries like construction, nearly a quarter of whose workers are living without legal authorization, is that their workforce is highly skilled and not easily replaced. Immigrant workers are particularly involved in home construction and specialize in such tasks as ceiling and flooring installation as well as roofing and drywall work.

Fewer available workers would mean slower home construction, which in turn would make housing more expensive, further compounding existing problems of housing supply and affordability.

Shocks from deportations would also slow commercial and public infrastructure construction. Six construction workers, for example, died in April 2024 in the sudden collapse of the Baltimore Key Bridge in Maryland. All of them were Latino immigrants living in the U.S. without legal documentation.

Examining the arguments

Trump administration officials and other politicians have argued that deporting large numbers of immigrants would help the country save money, since fewer people will use federal and state funds by attending public schools or receiving temporary shelter.

Trump said in November 2024 that there is “no price tag” for large-scale deportations.

“It’s not a question of price tag,” Trump said. “We have no choice. When people have killed and murdered, when drug lords have destroyed countries, and now they’re going to go back to those countries because they’re not staying here,” Trump told NBC News.

Trump and his supporters also argue that deporting immigrants would mean more jobs for American workers.

But there is compelling evidence to the contrary.

First, immigrants are filling labor shortages and doing jobs that many Americans don’t want to do, ones that might be unsafe or poorly paid.

Even if Americans were willing to do those jobs, there simply aren’t enough Americans in the workforce to fill existing labor vacuums, let alone an enlarged one following deportations.

Second, for employers, having fewer workers in the country translates into higher wages, which in turn means less capital to adapt and grow. For businesses based on consumer debt – think mortgages, car loans and credit cards – deportations would disrupt the financial sector by removing responsible borrowers who make consistent payments.

Third, immigrants living without legal documentation in the U.S. pay more than $96 billion in federal, state and local taxes per year and consume fewer public benefits than citizens.

Immigrants without legal authorization are not eligible for Social Security benefits and can’t enroll in Medicare or many other safety net programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

Rebecca Kiger for The Washington Post via Getty Images

The bottom line

In other words, people who are living and working in the U.S. without legal authorization are helping to pay, through taxes, the costs of caring for Americans as they age and begin to draw on the nation’s retirement and health care programs.

The burden from recent inflation notwithstanding, an economy supported by immigrants living illegally in the U.S. protects Americans.

The U.S. would be unable to dodge the economic shocks and high costs that mass deportations would bring about.![]()

Francisco I. Pedraza, Professor of political scinece, Arizona State University; Jason L. Morín, Professor of Political Science, California State University, Northridge, and Loren Collingwood, Associate Professor of political science, University of New Mexico

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.