Mississippi Today

Delta State’s future depends on $11 million, multi-year budget cut, president says

About a decade of “emergency-style budgeting” at Delta State University has all but maxed out its credit and created an $11 million hole that is poised to be an unavoidable existential threat.

Fixing the budget won’t be easy, Daniel Ennis, the new president, warned the campus during a town hall on Thursday. It must happen within five years and will require across-the-board cuts, including to salaries and positions, in part because the regional college’s single-best source of revenue — enrollment — has cratered by 48% in the last 16 years.

“Delta State has to exist,” Ennis said. “It must — for the Delta, for the region and for the state.”

The grim update comes a week after Ennis spoke to the Institutions of Higher Learning Board of Trustees during its annual retreat, which was held this year at the White House Hotel in Biloxi. Unlike most IHL board meetings, the retreats are not live-streamed.

“If I’m giving this information to the IHL, I should give it to you and then give you the opportunity to ask questions,” Ennis told the campus.

Though he presented roughly the same information at both events, Ennis expanded on the situation in Biloxi, telling trustees that he likely won’t be able to reduce the university’s budget from $51 million to $40 million without becoming the “most unpopular president in Delta State’s history.”

“I don’t care as long as there is another president at Delta State,” he said.

Al Rankins, the IHL commissioner, was also forthright about the stakes: “There’s nothing, nothing, nothing more important than the financial health” of Delta State.

“You have my support,” Rankins added, “because … any friends you have, you’re going to lose them.”

Delta State isn’t alone in some of the issues it faces — colleges across the country are struggling with declining enrollment and its resulting financial woes.

Much of that is outside Delta State’s control. The downturn in undergraduate students correlates “almost perfectly” with population loss in the Mississippi Delta, Ennis said at the town hall. In 2006, when the university had 3,298 undergraduate students, about 70% were from the Mississippi Delta — a percentage that has dropped to just over half of the 1,708 undergraduate students this year.

But, Ennis added, the university’s budget problems are largely self-inflicted. The budget is around $51 million when it should be more like $40 million.

In his first four months in office, Ennis said he found inadequate spending controls and contracted but unbudgeted expenses, such as an employee on payroll who had been hired with pandemic relief funds that had run out. The university repeatedly overestimated its revenue from facilities, merchandise and other non-tuition sources.

“The running of deficits year after year has eaten into our reserves,” he said.

And there were a number of “unexpected” and costly legal and personnel issues, which Ennis said weren’t clear to him when he applied for the job. Among those issues was a lawsuit from a former Iranian art professor who alleged he was discriminated against by the Turkish department chair. In late July, the university decided to settle after a federal court decided the case could go to trial.

“Every university and every large organization has legal and personnel issues,” Ennis said. “There was just, I thought, an unusual number for the size of the institution.”

In his first month of the job, Ennis said he had to find $1 million so the university could meet its statutory obligation to balance the books.

“I had one night of sleep and then the next day we’re in a new fiscal year with a new deficit already in place,” he said. “So, a challenge. Not what I expected, but that’s where we are.”

Though enrollment appears to be on the slight uptick — mainly due to an increase in graduate students — the university won’t clear its financial hurdles through better recruitment alone.

Delta State’s location in Cleveland puts it in a kind of double-bind: It exists to serve the Delta, but there are increasingly less people in the Delta.

“You should be really proud of the fact that you work at a place that cares about a disadvantaged group of people in a part of America that many folks write off or don’t even think about,” Ennis said. “The challenge is, if your investment is in recruiting students from the Delta, and the Delta writ-large is losing population at an alarming rate — for reasons that have nothing to do with Delta State and everything to do with social economic opportunity in other parts of the United States, then you can see we have declined.”

There has to be more fundraising, Ennis said. Delta State should be receiving more federal funding. He also committed to doubling the university’s capital campaign to $100 million. Though unorthodox, Ennis said this is his only chance to increase the endowment.

There will also be cuts that Ennis said will be decided through a budget committee composed of administrators, faculty and staff.

But individual sacrifices will have to be made, Ennis said. He tried to encourage everyone to not turn against each other — or against him — when it comes time for budget cuts.

“At a certain point there’s going to be less of everything,” he said. “Personnel, money, equipment and opportunities because we have to right-size the budget. And there’ll be all kinds of temptation to start thinking about my area, my budget, my place, my stakes.”

When Ennis took questions, Don Allan Mitchell, an English professor, said he understood that “everything is on the table” but wanted to know specifically if Ennis will also consider cuts from the presidential and vice presidential level. Ennis said yes.

Jamie Dahman, a professor who joined the music department in 2016, thanked Ennis for his seeming honesty and transparency.

“That’s something that’s been missing from Delta State leadership since I’ve been here,” he said.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

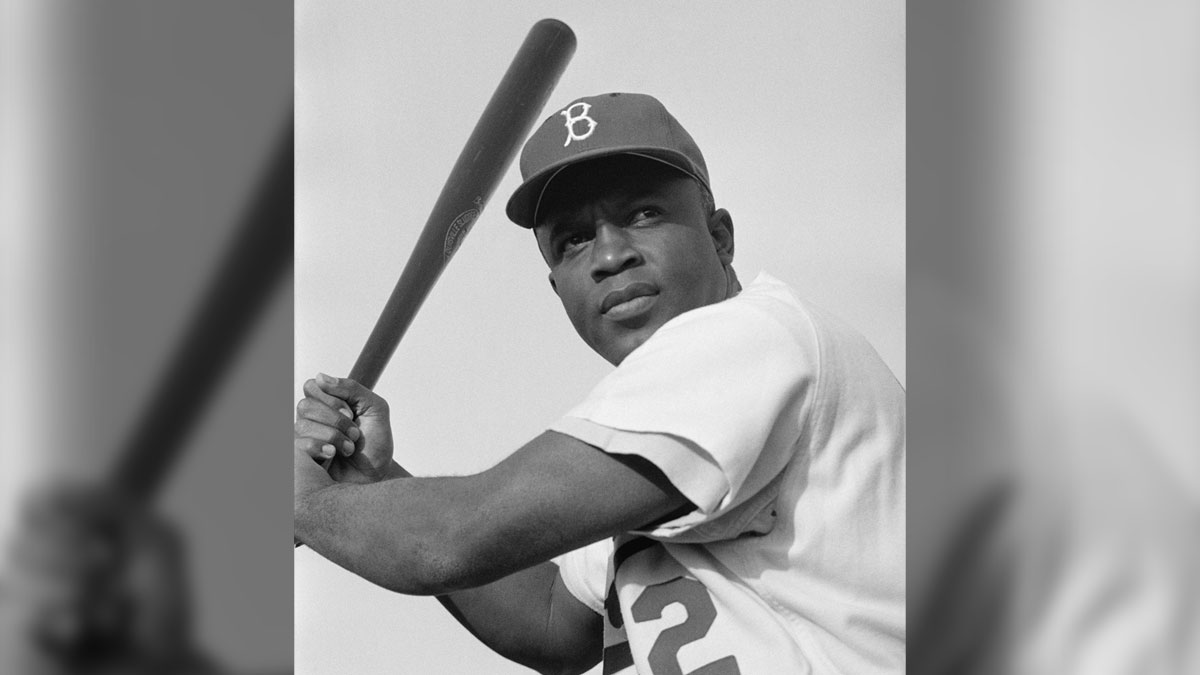

On this day in 1947, Jackie Robinson broke MLB color barrier

April 15, 1947

Jackie Robinson broke through the color barrier in Major League Baseball, becoming the first Black player in the 20th century.

Born in Cairo, Georgia, Robinson lettered in four sports at UCLA – football, basketball, baseball and track. After time in the military, he played for the Kansas City Monarchs in the Negro Leagues. After his success there, Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey signed Robinson, and the legendary baseball player started for Montreal, where he integrated the International League.

In addition to his Hall of Fame career, he was active in the civil rights movement and became the first Black TV analyst in Major League Baseball and the first Black vice president of a major American corporation.

In recognition of his achievements, Robinson was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Congressional Gold Medal.

Major League Baseball retired his number “42,” which became the title of the movie about his breakthrough.

Ken Burns’ four-hour documentary reveals that Robinson did more than just break the color barrier — he became a leader for equal rights for all Americans.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Mississippians highlight Black Maternal Health Week

Advocates and health care leaders joined lawmakers Monday morning at the Capitol to recognize Black Maternal Health Week, which started Friday.

The group was highlighting the racial disparities that persist in the delivery room, with Black women three times more likely to die of a pregnancy-related cause than white women.

“The bond between a mother and her baby is worth protecting,” said Cassandra Welchlin, executive director of the Mississippi Black Women’s Roundtable.

Rep. Timaka James-Jones, D-Belzoni, spoke about her niece Harmony, who suffered from preeclampsia and died on the side of the road in 2021 along with her unborn baby, three miles from the closest hospital in Yazoo City.

“It’s utterly important that stories are shared – but realize these are not just stories. This is real life,” she said.

The tragedy inspired James-Jones to become a lawmaker. She says she is working on gaining support to appropriate the funds needed to build a standalone emergency room in Belzoni.

But it isn’t just emergency medical care that’s lacking for some mothers. Mental health conditions are a leading cause of pregnancy-related deaths, defined as deaths up to one year postpartum from associated causes.

And more than 80% of pregnancy-related deaths are deemed preventable – making the issue ripe for policy change, advocates said.

“About 20 years ago, I was almost a statistic,” said Lauren Jones, a mother who founded Mom.Me, a nonprofit seeking to normalize the struggles of motherhood through community support. “I contemplated taking my life, I severely suffered from postpartum depression … None of my physicians told me that the head is connected to the body while pregnant.”

With studies showing “mounting disparities” in women’s health across the United States – and Mississippi scoring among the worst overall – more action is needed to halt and reverse the inequities, those at the press conference said.

The Mississippi Legislature passed four bills related to maternal health between 2018 and 2023, according to a study by researchers at the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

“How many times are we going to have to come before committees like this to share the statistics before the statistics become a solution?” Jones asked.

A bill that would require health care providers to offer postpartum depression screenings to mothers is pending approval from the governor.

Rep. Zakiya Summers, D-Jackson, the organizer of the press conference, commended the Legislature for passing presumptive eligibility for pregnant women this year. The policy will allow women to receive health care covered by Medicaid as soon as they find out they are pregnant – even if their Medicaid application is still pending. It was spearheaded by Rep. Missy McGee, R-Hattiesburg.

Summers also thanked Rep. Kevin Felsher, R-Biloxi, for pushing paid parental leave for state employees through the finish line this year.

Speakers emphasized the importance of focusing Black Maternal Health Week not just on mitigating deaths but on celebrating one of life’s most vulnerable and meaningful events.

“Black Maternal Health Week is a celebration of life, since Black women don’t often get those opportunities to celebrate,” said Nakeitra Burse, executive director of Six Dimensions, a minority women-owned public health research agency. “We go into our labor and delivery and pregnancy with fear – of the unknown, fear of how we’ll be taken care of, and just overall uncertainty about the outcomes.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Trump to appoint two Northern District MS judges after Aycock takes senior status

President Donald Trump can now appoint two new judges to the federal bench in the Northern District of Mississippi.

U.S. District Judge Sharion Aycock announced recently that she was taking senior status effective April 15. This means she will still hear cases as a judge but will have a reduced caseload.

“I have been so fortunate during my entire legal career,” Aycock said in a statement. “As one of only a few women graduating in my law school class, I had the chance to break ground for the female practitioner.”

A native of Itawamba County, Aycock graduated from Tremont High School and Mississippi State University. She received her law degree from Mississippi College, where she graduated second in her class.

Throughout her legal career, she blazed many trails for women practicing law and female jurists. She began her career as a judge when she was elected as a Mississippi Circuit Court judge in northeast Mississippi in 2002, the first woman ever elected to that judicial district.

She held that position until President George W. Bush in 2007 appointed her to the federal bench. After the U.S. Senate unanimously confirmed her, she became the first woman confirmed to the federal judiciary in Mississippi.

This makes Aycock the second judge to take senior status in four years. U.S. District Judge Michael Mills announced in 2021 that he was taking senior status, but the U.S. Senate still has not confirmed someone to replace him.

President Joe Biden appointed state prosecutor Scott Colom to fill Mills’ vacancy in 2023. U.S. Sen. Roger Wicker approved Colom’s appointment, but U.S. Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith blocked his confirmation through a practice known as “blue slips,” where senators can block the confirmation of judicial appointees in their home state.

This means President Trump will now have the opportunity to appoint two federal judges to lifetime appointments to the Northern District. U.S. District Judge Debra Brown will soon be the only active federal judge serving in the district. Aycock, Mills, and U.S. District Judge Glen Davidson will all be senior-status judges.

Federal district judges provide crucial work to the federal courts through presiding over major criminal and civil trials and applying rulings from the U.S. Supreme Court and the U.S. Court of Appeals in the local districts.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days agoMeasles cases confirmed in Arkansas children after travel exposure

-

Mississippi Today7 days ago

Mississippi Today7 days agoProgram helps students with disabilities forge paths to careers

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed7 days agoTax Day of April 15 is essentially May 1 in North Carolina | North Carolina

-

Mississippi Today6 days ago

Mississippi Today6 days agoA self-proclaimed ‘loose electron’ journeys through Jackson’s political class

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days agoImpacts of Overdraft Fees | April 11, 2025 | News 19 at 10 p.m.

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days agoSleeping 14-year-old critically injured by bullet in Ferguson home; father flees scene

-

News from the South - Tennessee News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Tennessee News Feed7 days agoQuestions mount over federal drug discount program | Tennessee

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days agoPilot Speaks on Helicopter Crash | April 10, 2025 | News 19 at 10 p.m.