News from the South - South Carolina News Feed

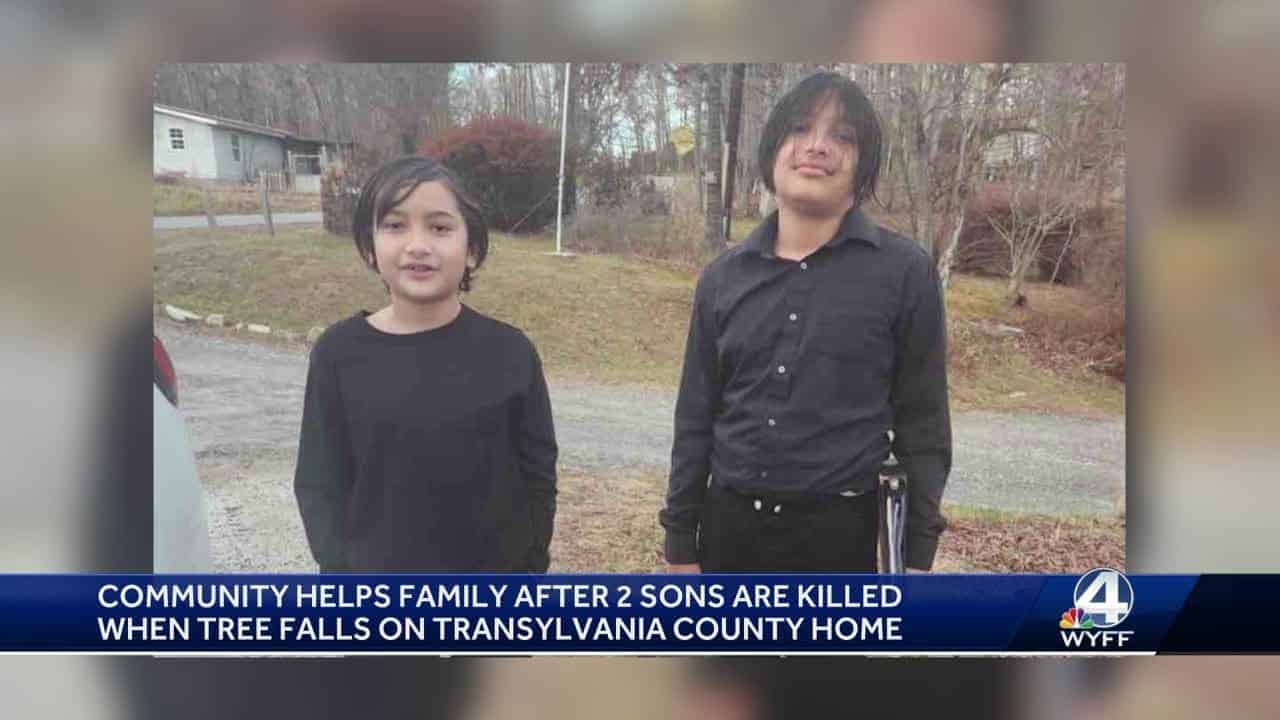

Community helps grieving family after tree kills two young boys

SUMMARY: In Transylvania County, North Carolina, a tragic incident occurred when a tree fell on a home, killing two young boys, 13-year-old Josiah and 11-year-old Joshua, while they were sleeping. The tree crashed through their mobile home during a storm with high winds. Community members are rallying to support the grieving family, with over $100,000 raised through a GoFundMe campaign for funeral, burial, and recovery expenses, including replacing their home and vehicle. Local churches and the Transylvania County School District are providing assistance, as the community remains resilient in the face of this heartbreaking tragedy.

Community helps grieving family after tree kills two young boys

Subscribe to WYFF on YouTube now for more: http://bit.ly/1mUvbJX

Get more Greenville news: http://www.wyff4.com

Like us: http://www.facebook.com/WYFF4

Follow us: http://twitter.com/wyffnews4

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/wyffnews4/

News from the South - South Carolina News Feed

Take a trip back in time to the birth of a nation

SUMMARY: Columbia, S.C. (WOLO) – Capital City/Lake Murray Country and 250 American Revolution: Lexington County invite media to cover “The Shot Heard Round The World” event on April 19, 2025, from 4:30 p.m. to 8:00 p.m. at Lexington’s Old Mill Pond Trail. This free, family-friendly event celebrates the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution, honoring the Battle of Lexington and Concord. Highlights include living history exhibits, lantern tours by Soda City Theatre Company, cannon demonstrations, and hands-on activities from local museums. A tribute featuring cinnamon whiskey will conclude the evening at 8:00 p.m., with a non-alcoholic option available.

The post Take a trip back in time to the birth of a nation appeared first on www.abccolumbia.com

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed

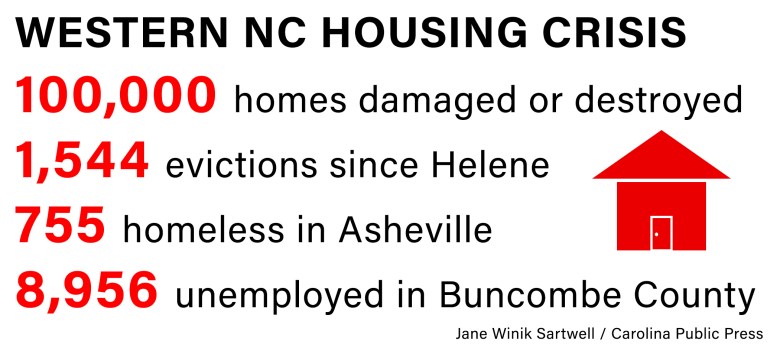

Evictions, high unemployment part of housing crisis in Western NC

With 1,500 evictions filed since Tropical Storm Helene, 100,000 housing units damaged or destroyed and an ever-growing number of people who are unemployed, the housing crisis in Western North Carolina has reached a fever pitch.

Asheville’s “unsheltered” homeless population — those living on the streets —reached 328 in the city’s 2025 count. That’s up more than 100 from the year before — a record high. The total number is 755, if you include those sleeping in shelters.

In the months since Tropical Storm Helene ravaged the region, there have been some minor wins. Like community organizations that have stepped up, offering unprecedented support to those struggling to keep a roof over their head.

[Subscribe for FREE to Carolina Public Press’ alerts and weekend roundup newsletters]

But in a region where affordable housing was already rare, the destruction of available homes, coupled with the loss of steady income for so many, has resulted in an even tighter squeeze.

People living on the streets. Or in tents. Or trailers.

It all adds to a picture of a region that has not fully recovered.

Hitting too close to home

The storm, which struck in late September 2024, came at the worst possible time for residents already struggling to make rent.

“It hit at the end of the month,” recalled Marcia Shoop, a pastor at Grace Covenant — a church that has become a lifeline for thousands facing housing insecurity. “Anybody that was late on their rent for September, they’re cooked because all of a sudden they don’t have wages.”

Many jobs — especially those in the service industry — still haven’t returned, leaving the mountain region with the highest unemployment rate across the state.

Grace Covenant Church has distributed $4.5 million in rental assistance since the storm. Even today, the house of worship is dispensing more than $90,000 weekly in rent checks. On a recent day in April, for example, 80 people walked through the doors in search of rent money.

But some organizations are finding it harder to provide help.

At Homeward Bound, a homeless agency in Asheville, housing placement has become more difficult.

“Ultimately, the hurricane increased the amount of street homelessness in Buncombe County and decreased the amount of vacancies that were available,” explained Ansley Carter, a housing placement manager at the organization.

Her team faces longer wait times to find housing for clients while simultaneously dealing with an influx of people in need of their placement services.

Many of Carter’s clients were living in the hotel rooms that the Federal Emergency Management Agency was providing as part of the agency’s temporary shelter assistance program. But now, that program has ended.

Numbers tell the evictions story

Homelessness in Asheville and across the mountains is on the rise, but at the same time, the rate of evictions hasn’t spiked the way activists were worried it might after the storm.

Though activists were gunning for an eviction moratorium that never materialized, the rate of evictions remained fairly steady before and after the storm. That’s because of two things, according to David Bartholomew, a housing attorney for Pisgah Legal Services in Asheville.

First, the Asheville Housing Authority paused all evictions for those who can’t afford to pay rent. And second: Rental assistance programs from FEMA, state and local governments as well as private organizations like Grace Covenant have helped people stay afloat.

But there’s been a massive increase in requests for Bartholomew’s legal services, he said. People are behind in rent, worried about what happens when FEMA assistance runs out and want to know more about their rights when it comes to negotiating with landlords.

Still, not everyone is safe from eviction.

Southwood Realty Company, which owns buildings in Asheville, Hendersonville and Waynesville, has filed 323 post-Helene eviction suits. For Michigan-based RHP Properties, which owns six developments in the Asheville area, that number is 262.

Smaller landlords have also been struggling. Some housing units that weren’t destroyed in the storm ended up being sold — and their tenants displaced — due to landlords leaving the area after Helene, according to Carter.

Homeowners are feeling a similar pain.

“The funds people are getting back from insurance aren’t enough to rebuild their homes,” explained Fabrice Julien, a professor of health science at UNC-Asheville. “I’ve had many friends whose homes were impacted during Helene, and what they ended up getting back from assessors and insurance companies, it just wasn’t enough.”

‘Chaos’ in Washington

The unpredictability of the Trump administration is further complicating recovery efforts in Western North Carolina.

The flow of $1.6 billion in federal disaster recovery funds promised by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development is in doubt.

“The uncertainty at the federal level is creating so much chaos that it is hard to figure out how to get the work done,” said Samuel Gunter, executive director of the North Carolina Housing Coalition. “We don’t know if resources are coming, and what this work of supporting people at the lower end of the income spectrum will look like. That money comes from a number of different buckets — HUD, USDA — and we just don’t know where the cuts are going to come from next.”

As the mountains prepare for summer tourism, the region is at a crossroads. With so many underemployed and unsure of when they’ll get their next rent check, the region needs the critical economic lifeline of visitors.

The question remains whether current assistance measures will bridge the gap until the area’s economy can fully recover.

This article first appeared on Carolina Public Press and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

The post Evictions, high unemployment part of housing crisis in Western NC appeared first on carolinapublicpress.org

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed

Briner hopeful AI will improve efficiency of state treasurer’s office

RALEIGH — In summer 1997, well before Brad Briner became state treasurer, he worked as an intern at the investment banking company Goldman Sachs.

While he was there, Briner needed to acquire data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. His supervisor offered him a plane ticket to the nation’s capital and told him to go down to the USDA building to comb through paper records and get the information he needed.

But the late 1990s marked a new age in technology. Briner knew there was a more efficient way to get the job done.

“I turned to him and said: ‘Hey, there’s this thing called the internet and I can actually just pull it for you right here,’” Briner recalled.

[Subscribe for FREE to Carolina Public Press’ alerts and weekend roundup newsletters]

Now, the Republican thinks the country is on the cusp of another one of those moments with the emergence of artificial intelligence — and he doesn’t want North Carolina stuck in the past.

To that end, in late March, Briner announced the launch of a 12-week pilot program in partnership with industry-leading company OpenAI to explore how artificial intelligence can be integrated into the work of the Office of the State Treasurer.

The announcement was made amid a push from state lawmakers to pass regulations on the use of AI in industries such as health care.

The contrast in approaches is representative of a larger national debate over the technology.

As artificial intelligence rapidly integrates into the private sector, public officials are exploring the best, and safest, ways to use the technology.

‘First of its kind’

The public-private partnership was hailed as the “first of its kind” following a flashy press conference to announce the initiative at N.C. Central University, but this is far from OpenAI’s first venture into government affairs.

For at least five years now, the federal government has been working towards integrating AI into its workforce under both Democratic and Republican administrations.

It started with a December 2020 executive order from Donald Trump that mandated departments and agencies “design, develop, acquire and use AI in a manner that fosters public trust and confidence while protecting privacy, civil rights, civil liberties and American values.”

Joe Biden continued that goal during his presidency by promising to hire 500 AI experts across the federal workforce by the end of fiscal year 2025.

And Trump has picked up right where he left off since returning to office.

On April 3, the Office of Management and Budget issued further guidance to federal agencies on acquisition and use of AI tools in accordance with Trump’s original order from 2020.

Starting last year, OpenAI announced a year-long pilot program with 14 state agencies in Pennsylvania. In March, Democratic Gov. Josh Shapiro called the program’s results “highly positive,” with average time savings of 95 minutes per day.

North Carolina is the next state to follow suit through its pilot program at the treasurer’s office.

The agency might not seem like an obvious candidate for an AI-powered makeover, but Briner, who was elected as a Republican in November, has an approach to finance that is not traditionally conservative. During his campaign, he criticized his predecessors for their risk-averse investment strategies he claimed consistently underperformed compared to other states. Briner has also advocated investing part of the state’s pension fund in cryptocurrency.

But despite the buzz and uncertainty associated with artificial intelligence, Briner said this partnership with OpenAI is anything but risky. Instead, it’s more like his office is trying to see if it’s a good fit.

Future for Briner is now

There are no legally binding ties or financial promises between the two parties yet.

Briner and OpenAI chief economic officer Ronnie Chatterji — a Durham resident and former Duke professor — signed a 12-week, non-binding memorandum of understanding that laid out the limited scope of the pilot program.

Notably, Chatterji ran as the Democratic candidate for state treasurer in 2020 and lost to Republican incumbent Dale Folwell. He and Briner also served together on the finance committee of a private school their children attended.

The memorandum of understanding signed by Briner and Chatterji states that the department will not pay OpenAI for any “off-the-shelf” use of ChatGPT — OpenAI’s flagship AI chatbot. But they may come to a separate payment agreement for more advanced integration of OpenAI’s technology.

The agreement does not get into much detail about what happens at the end of the program other than saying that the agency will deliver a final report of its findings and future recommendations.

Briner told CPP he is not committed to continuing with the program unless he sees “productivity growth” in the coming weeks.

Briner promises to be ‘respectful steward’

Briner assured that one of his top priorities in overseeing the program is being a “respectful steward of data,” and the agreement stipulates that OpenAI will not be given access to private information.

That is one “bright red line” Briner promised the initiative wouldn’t cross.

“The big issue with AI in state government,” Briner said, “is one that we are deliberately side-stepping, which is how do you ensure data privacy for non-public data in the context of using AI? That’s a big, thorny, complicated question, but we wanted to see if we could get tremendous productivity out of this tool by applying it only in the divisions where we don’t use private data.”

So the OpenAI program will focus on publicly-available datasets such as unclaimed property held by the state and the financial audits of local governments.

The state treasurer oversees an unclaimed property fund that holds more than $1.4 billion consisting of, among other things, bank accounts, wages and contents of safe deposit boxes that have been abandoned for years and turned over to the state. North Carolina runs a program called NC Cash dedicated to returning unclaimed funds to their owners.

Briner said that the division could use OpenAI’s tools to perform deep data searches to more easily identify and return property.

Moreover, the State and Local Government Finance Division, which audits the more than 1,100 units of local government in North Carolina each fiscal year, could use AI to flag potential financial issues.

Still, exactly how artificial intelligence technology would be used hasn’t been hammered out yet, but Briner said the goal is to see if the productivity in those two divisions will have improved by the time the pilot program expires in mid-May.

A hard line on software

Over at the state legislature, lawmakers appear to be more wary of artificial intelligence.

A couple of bills filed this year by state Sen. Jim Burgin aims to place more regulations over the use of AI chatbots.

“I’m really concerned about AI overall and the speed (at which it’s growing),” said Burgin, a Republican from Harnett County who has been a leader in the General Assembly on AI-focused policy. “It’s almost like one of those Chia heads. It’s got a little bit of water and it’s growing everywhere, and we need to think about that.”

One of the bills sponsored by Burgin — Senate Bill 624 — would require operators of AI-powered chatbots in the health care sector to be licensed by the state. It would also require operators of any chatbot to inform users that the computer program is “not human, human-like or sentient.”

Furthermore, it would give a state attorney general the power to sue chatbot operators in violation of those regulations.

A spokesman for Attorney General Jeff Jackson declined to comment on the bill other than to say that the office was “currently reviewing” the legislation.

Burgin, who is the president and owner of an insurance company, said he’s not opposed to the use of AI. What he’s trying to do is put up guardrails to prevent harmful misuse of the emerging technology.

“Do I think that there’s some exciting things about it? Yeah, I think there’s unlimited possibilities.”

This article first appeared on Carolina Public Press and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

The post Briner hopeful AI will improve efficiency of state treasurer’s office appeared first on carolinapublicpress.org

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days agoImpacts of Overdraft Fees | April 11, 2025 | News 19 at 10 p.m.

-

Mississippi Today6 days ago

Mississippi Today6 days agoOn this day in 1873, La. courthouse scene of racial carnage

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days agoMom and son targeted in carjackings, stolen cars crime spree

-

Local News6 days ago

Local News6 days agoAG Fitch and Children’s Advocacy Centers of Mississippi Announce Statewide Protocol for Child Abuse Response

-

Mississippi Today6 days ago

Mississippi Today6 days agoLawmakers used to fail passing a budget over policy disagreement. This year, they failed over childish bickering.

-

Local News5 days ago

Local News5 days agoSouthern Miss Professor Inducted into U.S. Hydrographer Hall of Fame

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed4 days agoFoley man wins Race to the Finish as Kyle Larson gets first win of 2025 Xfinity Series at Bristol

-

Mississippi News Video7 days ago

Mississippi News Video7 days ago4/11/25- Beautiful weekend weather is expected