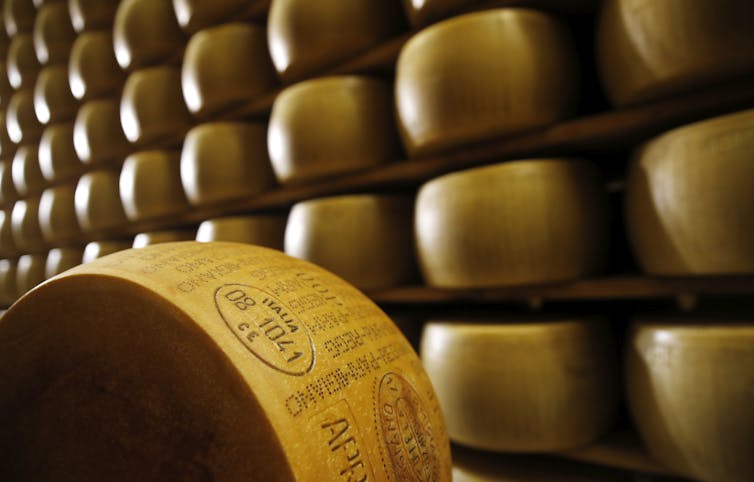

AP Photo/Antonio Calanni

John A. Lucey, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Cheese is a relatively simple food. It’s made with milk, enzymes – these are proteins that can chop up other proteins – bacterial cultures and salt. Lots of complex chemistry goes into the cheesemaking process, which can determine whether the cheese turns out soft and gooey like mozzarella or hard and fragrant like Parmesan.

In fact, humans have been making cheese for about 10,000 years. Roman soldiers were given cheese as part of their rations. It is a nutritious food that provides protein, calcium and other minerals. Its long shelf life allows it to be transported, traded and shipped long distances.

I am a food scientist at the University of Wisconsin who has studied cheese chemistry for the past 35 years.

In the U.S., cheese is predominantly made with cow’s milk. But you can also find cheese made with milk from other animals like sheep, goats and even water buffalo and yak.

Unlike with yogurt, another fermented dairy product, cheesemakers remove whey – which is water – to make cheese. Milk is about 90% water, whereas a cheese like cheddar is less than about 38% water.

Removing water from milk to make cheese results in a harder, firmer product with a longer shelf life, since milk is very perishable and spoils quickly. Before the invention of refrigeration, milk would quickly sour. Making cheese was a way to preserve the nutrients in milk so you could eat it weeks or months in the future.

How is cheese made?

All cheesemakers first pump milk into a cheese vat and add a special enzyme called rennet. This enzyme destabilizes the proteins in the milk – the proteins then aggregate together and make a gel. The cheesemaker is essentially turning milk from a liquid into a gel.

After anywhere from 10 minutes to an hour, depending on the type of cheese, the cheesemaker cuts this gel, typically into cubes. Cutting the gel helps some of the whey, or water, separate from the cheese curd, which is made of aggregated milk and looks like a yogurt gel. Cutting the gel into cubes lets some water escape from the newly cut surfaces through small pores, or openings, in the gel.

The cheesemaker’s goal is to remove as much whey and moisture from the curd as they need to for their specific recipe. To do so, the cheesemaker might stir or heat up the curd, which helps release whey and moisture. Depending on the type of cheese made, the cheesemaker will drain the whey and water from the vat, leaving behind the cheese curds.

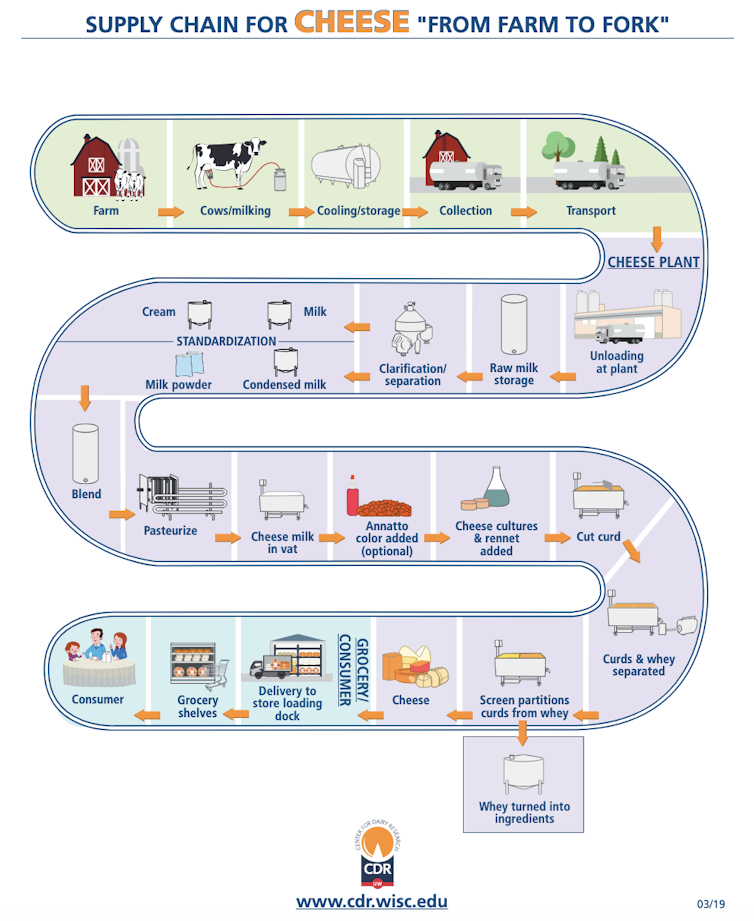

UW Center for Dairy Research

For a harder cheese like cheddar, the cheesemaker adds salt directly to the curds while they’re still in the vat. Salting the curds expels more whey and moisture. The cheesemaker then packs the curds together in forms or hoops – these are containers that help shape the curds into a block or wheel and hold them there – and places them under pressure. The pressure squeezes the curds in these hoops, and they knit together to form a solid block of cheese.

Cheesemakers salt other cheeses, like mozzarella, by placing them in a salt solution called a brine. The cheese block or wheel floats in a brine tank for hours, days or even weeks. During that time, the cheese absorbs some of the salt, which adds flavor and protects against unwanted bacterial or pathogen growth.

UW Center for Dairy Research

Cheese is a living, fermented food

While the cheesemaker is completing all these steps, several important bacterial processes are occurring. The cheesemaker adds cheese cultures, which are bacteria they choose that produce specific flavors, at the beginning of the process. Adding them to the milk while it is still liquid gives the bacteria time to ferment the lactose in the milk.

Historically, cheesemakers used raw milk, and the bacteria in the raw milk soured the cheese. Now, cheesemakers use pasteurization, a mild heat treatment that destroys any pathogens present in the raw milk. But using this treatment means the cheesemakers need to add back in some bacteria called starters – these “start” the fermentation process.

Pasteurization provides a more controlled process for the cheesemaker, as they can select specific bacteria to add, rather than whatever is present in the raw milk.

Essentially, these bacteria eat (ferment) the sugar – the lactose – and in doing so produce lactic acid, as well as other desirable flavor compounds in the cheese like diacetyl, which smells like hot buttered popcorn.

In some types of cheese, these cultures stay active in the cheese long after it leaves the cheese vat. Many cheesemakers age their cheeses for weeks, months or even years to give the fermentation process more time to develop the desired flavors. Aged cheeses include Parmesan, aged cheddars and Gouda.

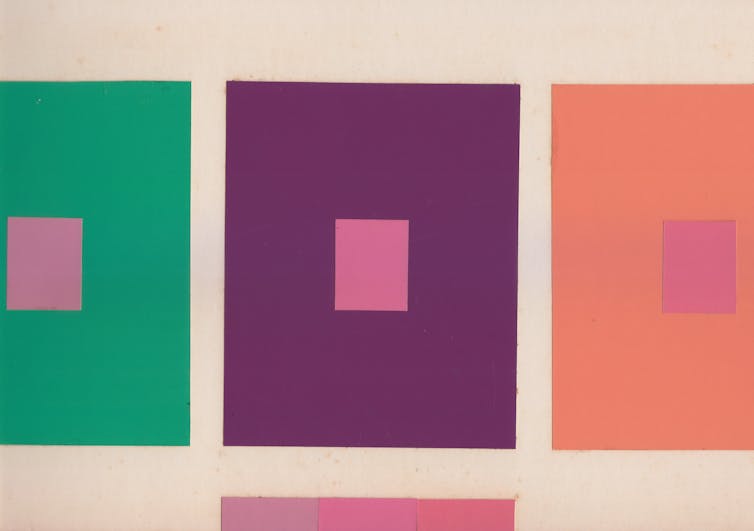

The Dairy Farmers of Wisconsin

In essence, cheesemaking is a milk concentration process. Cheesemakers want their final product to have the milk proteins, fat and nutrients, without as much of the water. For example, the main milk protein that is captured in the cheesemaking process is casein. Milk might contain about 2.5% casein content, but a finished cheese like cheddar may contain about 25% casein (protein). So cheese contains lots of nutrients including protein, calcium and fat.

Infinite possibilities with cheese

There are hundreds of different varieties of cow’s milk cheese made across the globe, and they all start with milk. All of these different varieties are produced by adjusting the cheesemaking process.

For some cheeses, like Limburger, the cheesemaker rubs a smear – a solution containing various types of bacteria – on the cheese’s surface during the aging process. For others, like Camembert, the cheesemaker places the cheese in an environment (e.g., a cave) that encourages mold growth.

Others like bandaged cheddar are wrapped with bandages or covered with ash. Adding a bandage or ash onto the cheese’s surface helps protect it from excessive mold growth, and it reduces the amount of moisture lost to evaporation. This creates a harder cheese with stronger flavors.

Dairy Farmers of Wisconsin

Over the past 60 years, cheesemakers have figured out how to select the right bacterial cultures to make cheese with specific flavors and textures. The possibilities are endless, and there’s no limit to the cheesemaker’s imagination.![]()

John A. Lucey, Professor of Food Science, University of Wisconsin-Madison

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.