Mississippi Today

Big Companies Cashed In on Mississippi’s Water. Small Towns Paid the Price.

Sarah Fowler is reporting on the water crisis in Jackson, Miss., in the state where she was born and raised, as part of The Times’s Local Investigations Fellowship.

In winter 2021, more than 150,000 people living in Jackson, Miss., were left without running water.

Faucets were dry or dribbling a muddy brown. For weeks, people across the city lost the water they normally relied on to drink, cook and bathe. With no way to flush their toilets, some parents sent their children into the woods to relieve themselves. Businesses closed. Mississippi’s capital effectively shut down.

The following year, at the height of Mississippi’s sweltering summer in August 2022, it would all happen again.

Each time Jackson faced a water crisis, local and state leaders cast blame in familiar directions. Lawmakers criticized city officials for ignoring leaky pipes and failing to collect payments from customers. City officials pointed to Jackson’s shrinking population and decades of economic decline. And they said state officials, mostly white and Republican, had starved the mostly Black, Democratic city of resources.

But the final blow was delivered by Siemens, a giant German corporation that had swept into town in 2010, boldly promising to install modern water meters that would boost revenues and return Jackson’s water system to a moneymaking enterprise that could afford to fix its crumbling infrastructure.

Siemens, better known for building power plants and high-speed trains, failed to deliver on its promises. Jackson found itself with many meters that didn’t work and wildly inaccurate water bills it couldn’t collect.

Siemens returned the $90 million it had been paid for the project. But the damage was done. Jackson was out more than $450 million in fees and lost revenue. It had no way to repair failing equipment and aging pipes that left city water unsafe to drink and ultimately led to a federal takeover of the water system in December 2022.

The outlines of Siemens’s role in Jackson’s water issues were laid out publicly in 2019, when the city sued the company. But Jackson was not the only Mississippi city that fell victim to the promise of easy money.

A yearlong New York Times investigation, drawing on thousands of pages of government records and interviews with city officials across the state, reveals how Siemens and other corporations went from one small, cash-strapped town to the next making grand promises to modernize water systems and boost revenues. It also sheds new light on the involvement of a state agency that was supposed to vet the deals.

In town after town, salesmen lured city officials who had little expertise in water meters with gee-whiz technology and complicated cost-saving algorithms. They said the meters could be installed at no cost to taxpayers and offered cash-back guarantees.

Even when meters started failing in large numbers and cities complained they were on the verge of financial disaster, the companies kept selling their services.

For nearly a decade, three companies — Siemens; the Mississippi-based McNeil Rhoads, started by a former Siemens salesman, Chris McNeil; and the North Carolina water meter manufacturer Mueller — crisscrossed the state signing multimillion-dollar deals in cities desperate for money.

Mr. McNeil pitched most of the deals, first for Siemens, then for his own company. He claimed that Mueller’s “smart” meters would be so accurate and efficient they would more than pay for themselves. In accordance with state policy at the time, every project was reviewed by the Mississippi Development Authority, an agency run by executives appointed by the governor.

From 2009 to 2017, at least 10 Mississippi cities signed contracts with the companies to install smart meters or other new technology. All but one have reported problems, and at least four have sued to recoup money they paid to Siemens, McNeil Rhoads or Mueller. Three of those suits are still pending.

Siemens and McNeil Rhoads, competitors that pitched the projects and acted as project managers, hired contractors who installed many meters improperly, according to officials in Jackson, McComb and Moss Point. In some cities, the two companies also struggled to link meters to the home office or to merge a new billing system with an old one.

Officials in at least eight Mississippi cities said they had problems with Mueller’s smart meters, which sometimes didn’t measure accurately because of faulty parts or batteries that died sooner than promised. Water departments in other states, including California and Missouri, have reported similar problems with Mueller meters over the past decade.

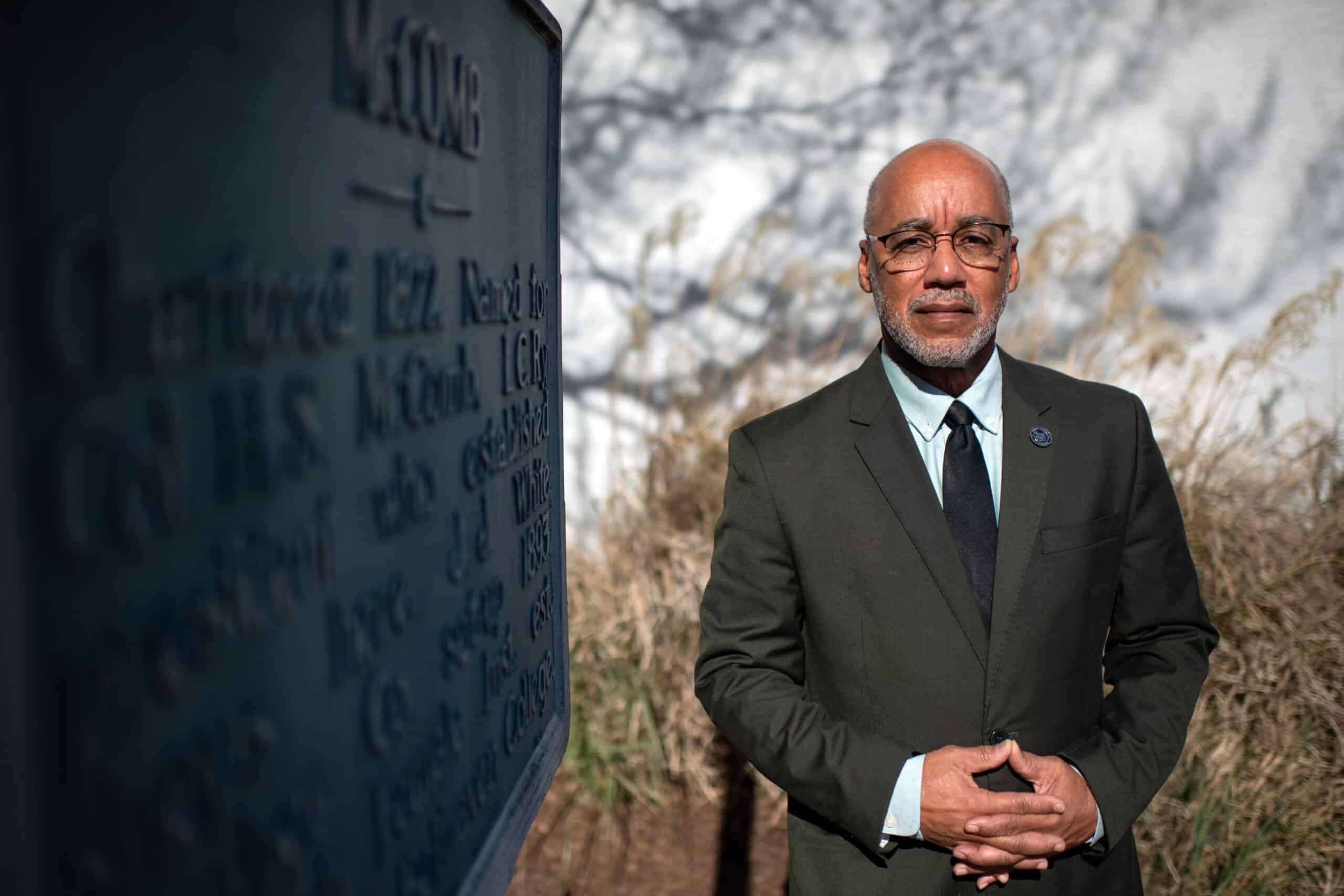

McComb, a city of 12,000 people south of Jackson, signed the first Siemens water meter contract in Mississippi. Mayor Quordiniah N. Lockley, city manager at the time, said McComb agreed to pay the company $10 million to install 6,000 smart Master Meters.

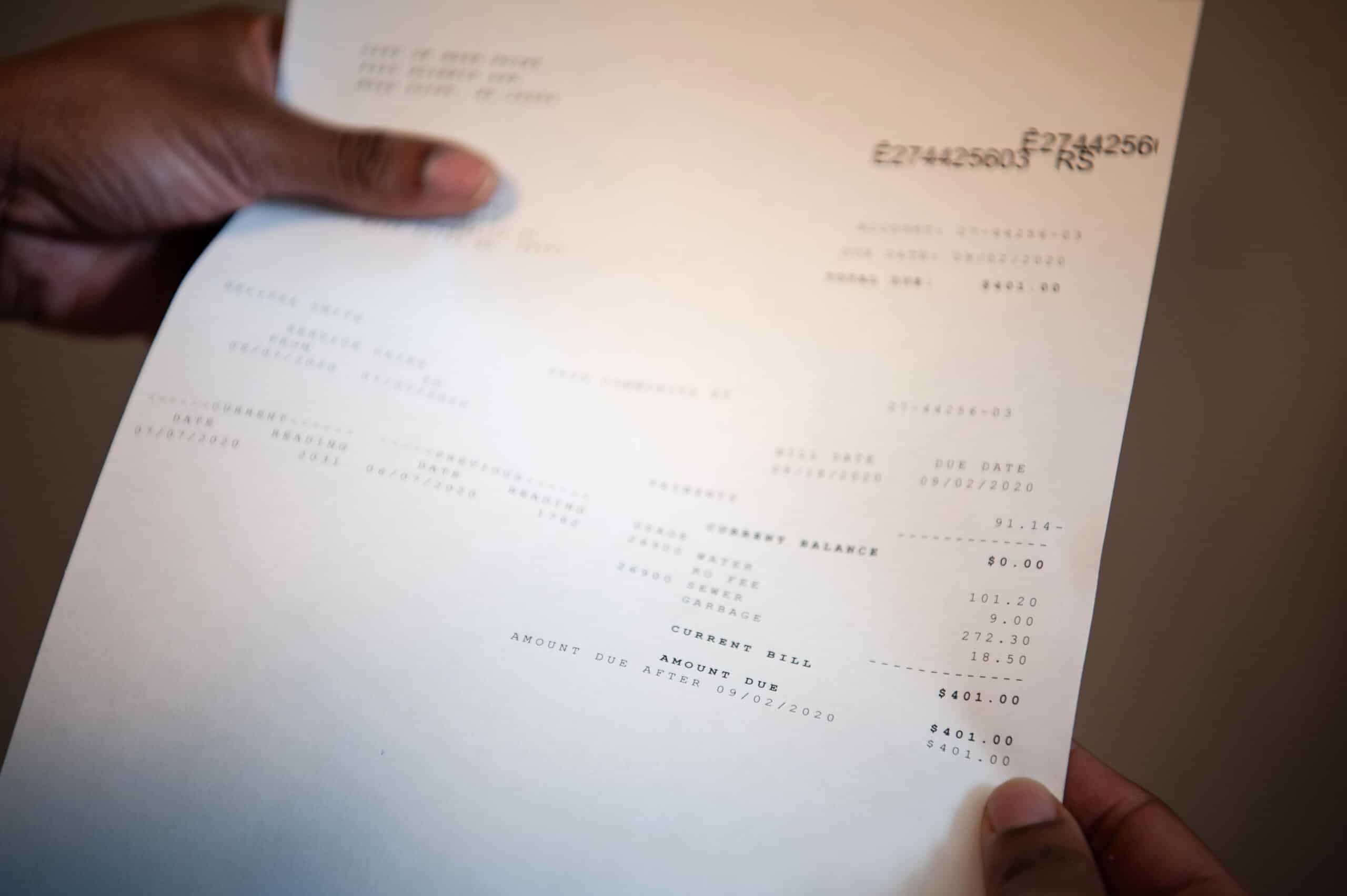

But contract workers hired by Siemens put them in backward and missed deadlines to install the antennas that the meters needed to communicate with a central office, Mr. Lockley said. Then some customers saw their water bills hit as much as $1,000 per month, with no obvious explanation.

Mr. Lockley said he called a friend, whom he declined to name, on the Jackson City Council and warned him not to go forward with the developing Siemens deal there.

He said he had one message: “Run.”

“Just because they come in a suit and tie doesn’t mean they’re not selling snake oil,” Mr. Lockley said in an interview.

Even as lawsuits and complaints from customers mounted, the companies continued making the same promises, and state and city officials continued approving contracts.

Jackson ultimately signed a deal with Siemens to install Mueller meters, the largest contract in the city’s history. Officials in Cleveland, a small city in the Mississippi Delta, inked a deal with Siemens for Mueller meters as well. Columbus, Meridian and Moss Point — all largely Black cities of fewer than 35,000 people — hired McNeil Rhoads to install Mueller meters.

Officials in some of the cities say they have been financially crippled.

In a letter to the development authority and the state attorney general, Jamie Lee, the city attorney for Cleveland, wrote that hundreds of meters were malfunctioning and the issue “could lead Cleveland into a major financial deficit if not addressed immediately.” She asked for “the assistance of your two offices in achieving a resolution with Siemens.”

Ms. Lee said she never received a response.

In a statement that did not address complaints by other Mississippi cities, a Siemens spokeswoman, Annie Satow, said the company had invested significant work in Jackson to “help navigate persistent challenges outside the company’s control,” including “substantial assistance beyond contractual requirements” with the billing system.

“Siemens acted in good faith, worked cooperatively with city personnel and was transparent and responsive to oversight by the city’s administration and Department of Public Works,” she wrote.

Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba of Jackson said that while he couldn’t discuss the specifics of the deal, Siemens was not entirely to blame. Jackson, he said, willingly entered into a bad agreement. He declined to elaborate, and his office did not respond to repeated requests for an interview. Since the federal takeover, which came with an infusion of $600 million and a third-party manager to run the water system, leaks are being repaired and citywide boil-water notices have drastically diminished.

Mr. McNeil did not return numerous calls seeking comment. A Mueller spokesman and other executives did not respond to repeated calls and emails.

Records show that Siemens and Mueller made attempts to replace or repair some meters in the cities where problems arose, but the cites still lost money and some, including Jackson, McComb and Moss Point, had to pay to replace meters or other technology on their own.

Reached by phone, Glenn McCullough, executive director of the Mississippi Development Authority from 2015 to 2020, said he had not been aware of widespread problems with Siemens, McNeil Rhoads or Mueller. He referred questions to the agency’s spokeswoman, Tammy Craft, who declined to comment.

“We can’t speak on this any further, since no one involved in reviewing these contracts back-when is at M.D.A. anymore,” Ms. Craft wrote.

But she noted that in 2017, state lawmakers passed a bill ending M.D.A.’s oversight of such contracts.

A promising solution for an ailing system

At the time Jackson was considering a deal with Siemens, the water industry was in the midst of a major transition. New technologies had made it possible for sensors to more accurately measure water use. Smart meters could eliminate the need for meter readers to visit homes to calculate people’s water bills, a huge potential savings for utility departments.

Manufacturers, including Mueller, saw the technology as a critical part of their future. But only if they could convince municipal water departments it was worth spending millions of dollars to replace old equipment. In financial statements filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission in 2015, Mueller described water utilities as slow adopters of the technology because of installation costs.

The water industry found a solution in the growing effort to make public agencies and schools more energy-efficient.

As far back as the 1980s, the federal government had been supporting partnerships with private companies to retrofit buildings with more efficient equipment.

Under energy performance contracts, municipalities could borrow money and use it to hire private contractors to replace old light fixtures, air-conditioning units and other appliances. Savings from lower electric bills would then be used to pay off the debt, allowing cities to invest in improvements at no real cost to taxpayers.

The contracts had made Siemens tens of millions of dollars in Mississippi alone and allowed a financially struggling state to afford equipment upgrades that otherwise might have been out of reach.

Then, two years before Siemens pitched a plan to help Jackson fix its ailing water system, the Mississippi attorney general’s office issued an opinion that helped pave the way for even more ambitious projects.

In 2008, the office reviewed the state statute governing energy performance contracts and concluded that cities and school districts could use them to finance projects that conserved water, not just energy.

An opportunity ‘too good to pass up’

In 2009, a decade before Jackson officials sued Siemens over failed meters, the company signed its first water contract in the state in tiny McComb.

McComb had boomed as a railroad city in the 1870s, carved out of a dense pine forest about halfway between Jackson and New Orleans.

Today it resembles a lot of small Mississippi towns: Its shrinking population is almost 75 percent Black. One in three people live under the poverty line. A downtown resurgence has begun, but money for civic improvements is in short supply.

So when Siemens offered a way to fill city coffers through the water department, the opportunity seemed too good to pass up.

According to Mr. Lockley, Siemens told city officials they would be able to disconnect someone’s water with the touch of a button while sitting in their office. New smart meters would measure water use remotely and more accurately.

Siemens said the meters would boost revenues by more than $600,000 a year, sales materials show. And city officials believed McComb would be “one of the top water departments in the state,” Mr. Lockley recalled.

McComb paid Siemens to replace 6,000 water meters, but computer software glitches and delays in installing communication antennae left the city unable to monitor water usage remotely, Mr. Lockley said. Residents also began complaining of erroneous water bills.

When McComb tried to cancel the contract, Siemens sued and the case went to mediation. To get out of the contract, McComb agreed to pay for the meters already in the ground at a cost of $2 million to $3 million, Mr. Lockley said. Then the city hired another company to install software that allowed the meters to function.

Mr. Lockley said he has never spoken publicly about the settlement before because he signed a nondisclosure agreement.

“They tie your hands, say you can’t talk about the situation, and it just keeps happening,” Mr. Lockley said.

Jackson’s crippling ‘sweetheart deal’

Even as problems arose in McComb, Mr. McNeil used the city as a selling point to win new business for Siemens.

Mr. McNeil had been a local football standout in Petal, Miss., before becoming an offensive lineman at Mississippi State University in the early 2000s. He previously had secured a 15-year contract for Siemens to overhaul lighting, air-conditioning and traffic lights throughout Jackson.

He and a fellow salesman, Dusty Rhoads, the son of the mayor of nearby Flowood, traveled the state, pitching similar contracts to financially strapped towns. They eventually left Siemens and started their own company, McNeil Rhoads, signing smart meter contracts with at least six cities.

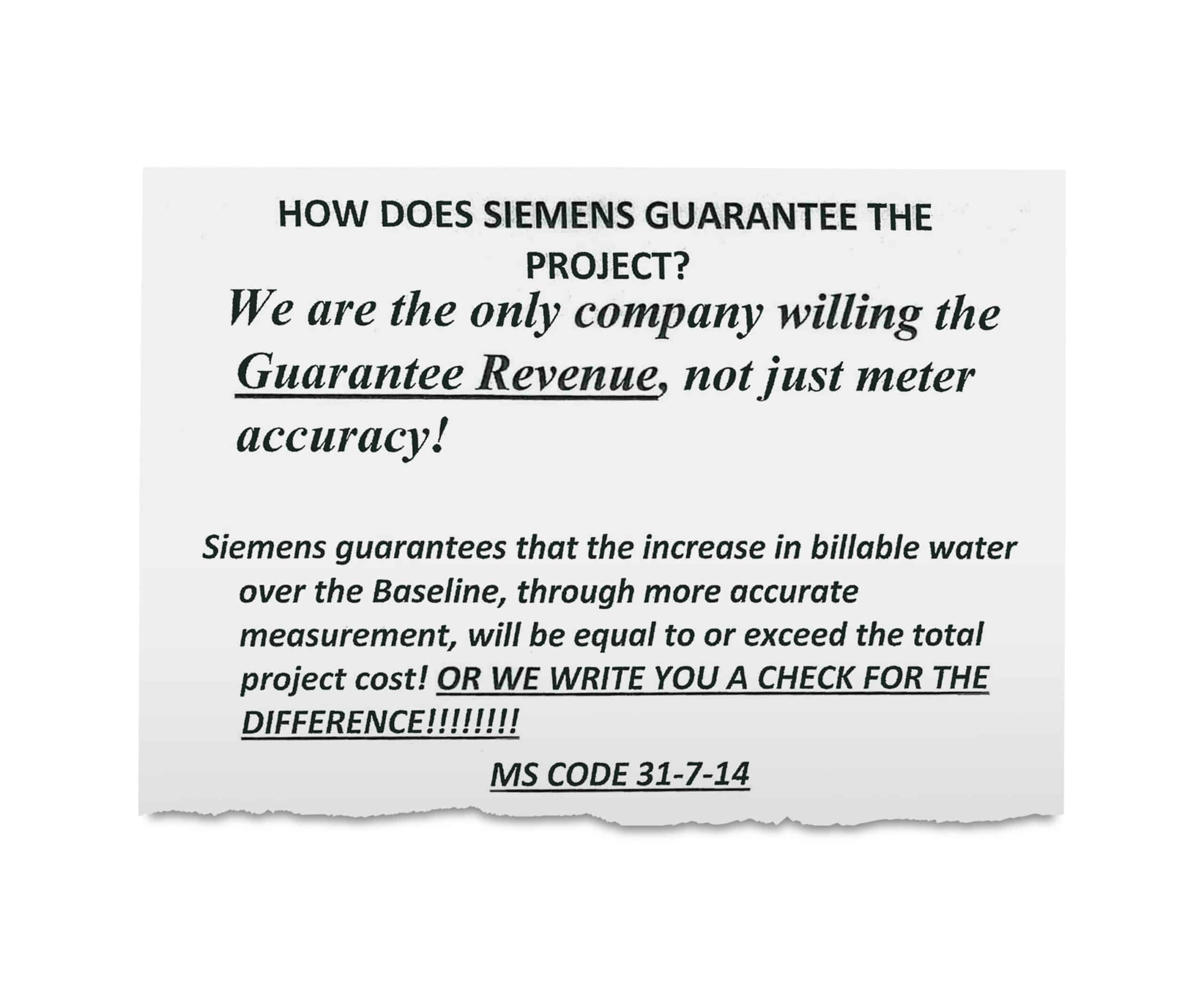

When pitching to Cleveland, Mr. McNeil, representing Siemens, noted the McComb contract in a sales presentation, city records show. Savings were “guaranteed,” his slide show said. If they fell short, “we will write you a check for the difference.” The statement was followed by eight exclamation points.

In September 2010, Mr. McNeil sent the first in a series of emails to the Public Works Department in Jackson. He had a plan to replace the city’s water meters and make critical repairs to its infrastructure. The project would create jobs, he promised, and the new meters would cover the cost of installation — or else the company would.

Mr. McNeil pursued Jackson officials for two years and backed up his cost-saving claims with a Siemens-funded study of the meters. All of this, he said, had already been done down the road in McComb.

By the end of 2012, Jackson was on the verge of signing a $90 million deal that the city would later estimate cost it $450 million in expenses and lost revenues.

Based on an email Mr. McNeil sent to Jackson’s public works director then, Dan Gaillet, at least one Jackson official was aware of the project in McComb. But Mr. Lockley said no one called him about it and his warning was ignored.

Problems emerged just weeks into the Jackson project. A politically connected subcontractor, hired by Siemens at the recommendation of city officials, had installed some meters improperly, and later, there were communication errors between the meters and receivers. Some meters showed customers not using any water, while others got huge bills that city officials said were implausible.

Unable to calculate realistic bills, Jackson officials stopped collecting from thousands of customers.

The loss of revenue exacerbated years of neglect and poor decision-making and left the water department in dire financial straits and residents facing a near continuous string of boil-water notices. City officials would later accuse subcontractors involved with the project of contributing to the problems, something they deny.

A former Jackson councilman, Melvin Priester, was elected after the city had signed the deal but before groundbreaking had begun. He voiced his objections but was in the minority.

Siemens got a “sweetheart deal,” Mr. Priester told The Times, but “when you are in bad straits like the City of Jackson is now and was in 2013, all of your options are bad deals.”

Calls for help went unanswered

The Mississippi Development Authority, which greenlit the project, was created in 2000 as an economic engine for the state. It directs tax credits to attract companies and gives out millions of dollars in grants to spur revitalization efforts.

As far back as 2010, it also played a role in reducing local energy and water use.

If a city wanted to borrow against future savings for a retrofit project, it had to submit a request to the development authority. State law required the authority to review and approve each contract to “assure that entities can rely upon projected and guaranteed energy savings,” according to policies that were in effect until 2017.

The reviews, conducted by licensed engineers outside the authority, were seen as a critical backstop by city officials, who often lacked the expertise or resources to verify companies’ promises.

“M.D.A. legitimized it,” said Amy St. Pe’, Moss Point’s city attorney, who is suing McNeil Rhoads and Mueller. “Any doubts that we had, when we saw that M.D.A. was backing the program, we felt that it had to be good for the city.”

During a sales pitch, Mr. McNeil cited the agency’s approval process to dispel naysayers in Harrison County, a Gulf Coast community that was considering a project with his company. At a September 2014 meeting, the board of supervisors worried that the county could be left millions in debt if the savings didn’t pan out, according to an article in The Biloxi Sun Herald. Mr. McNeil responded by saying the project was “100 percent regulated by the Mississippi Development Authority,” and the board voted unanimously in favor.

Records show the agency often engaged in back-and-forth with cities seeking approval of the contracts. No application prompted more scrutiny than Jackson’s.

When the development authority reviewed Siemens’s proposal, it raised more than 200 questions, asking how the work being described could possibly save the city money. Mayor Harvey Johnson Jr. sent a 19-page reply that answered and largely dismissed those concerns. One week later, in March 2013, the agency signed off on the contract.

From 2009 to 2017, at least 12 cities pursued energy performance contracts that the agency reviewed, a number of them involving water projects.

Companies pitching the work came up with predicted cost savings using their own methods, records show. Siemens’s estimate, for example, depended largely on how much more accurate new meters would be than old meters. But nowhere in the state’s analysis did engineers ask Siemens or the other companies to prove their calculations.

In a review of hundreds of pages of correspondence between the agency and local officials, The Times did not find a single instance when state officials passed on information about problems cities were experiencing with Siemens, McNeil Rhoads or Mueller.

In fact, when cities directly reported problems and begged the agency for help, they found themselves on their own.

Ms. Lee, the Cleveland city attorney, said she, the mayor and at least two aldermen sought guidance from the agency to no avail.

Ms. Lee wrote her letter in May 2018. A year later, in August 2019, when the city was already embroiled in a lawsuit with Siemens and Mueller, Alderman Gary Gainspoletti sent another letter, pleading with officials as the city was trying to “stop the bleeding.”

An agency official acknowledged receipt, but help never came.

Mr. McCullough, the agency’s executive director at the time, said, “I don’t recall seeing any document regarding defective water meters coming to my desk.”

Warning signs emerge nationwide

For years as companies installed Mueller meters across Mississippi, the meter manufacturer was aware of problems with its products in other states, including California and Missouri.

In 2012, the same year Cleveland was putting faulty water meters in the ground and Jackson was signing its contract, Mueller alerted a water authority in Missouri that some meters had defective magnets that would break, preventing them from recording water consumption, according to a regulatory report. The water authority returned the meters to Mueller for repair.

Years later, a federal class action lawsuit filed in New York by a Mueller shareholder alleged that executives had “misled the investing public” by not being honest about the failure rate of smart meters. The suit was dismissed in 2020, but sworn statements by three confidential informants suggested that Mueller was struggling with high failure rates as early as 2013.

That is when San Diego officials realized that a connection problem was preventing many of the meters from recording data, according to one of the witnesses, described in the suit as a regional manager for Mueller. Residents complained for years of abnormally high bills. The same issues would arise in Jackson and other Mississippi cities.

The suit also pointed out problems that year in Missouri. Mueller replaced nearly 80 percent of water meters in Chillicothe after moisture was found in parts that were supposed to be dry. By 2019, because of battery issues, the replacement meters had a failure rate of 89 percent.

The largest investigation into Mueller by a public utility would unfold in the state. From 2012 to 2015, Missouri American Water installed thousands of Mueller meters. Regulators reported that the meters had “several different kinds of defects,” leading to inaccurate readings or none at all. In August 2015, the utility began a costly campaign to replace 24,000 of the nearly 100,000 that had been installed.

All the while, Mueller was touting its smart meters as a critical driver of growth and telling investors that municipal governments would increasingly seek out the new technology.

‘They preyed on disadvantaged cities’

Mr. McNeil continued to push Mueller meters. After winning Siemens the Jackson contract, he started his own company and used the meters in energy performance contracts he landed across Mississippi — in Columbus, Gautier, Grenada, Meridian, Moss Point and Tupelo.

Seven years after signing in 2014, Columbus Light and Water Department reported excessive failure rates and began pressing Mueller to make good on an extended warranty it had promised. Early on, the company was responsive, answering emails and sending a batch of parts, according to department records. But when complaints continued, Mueller employees stopped answering the department’s questions, said Mike Bernsen, the utility’s interim general manager in 2021.

“We played it through the channels as far as we could.” Mr. Bernsen said.

Frustrations with getting Mueller officials to respond continued into 2022, emails show. In a series of emails early that year, department officials asked Mueller for a meeting to discuss the increasing number of failing meters, but after weeks without an answer, they concluded the company was avoiding them.

Moss Point, signing with McNeil Rhoads in 2017, discovered problems almost immediately, according to Ms. St. Pe’, the city attorney. Residents’ bills were improbably high, and Mueller initially offered batches of replacement devices.

But then, once the city filed suit, the company claimed it was under no obligation to replace the meters because the city had bought them from McNeil Rhoads, not directly from Mueller. Mueller stopped responding and McNeil Rhoads went out of business, leaving Moss Point with little financial recourse, Ms. St. Pe’ said.

“McNeil Rhoades is who convinced us to purchase these water meters,” she said. “I feel like they preyed on disadvantaged cities, predominantly African American cities.”

Out of the six known cities that hired McNeil Rhoads, four are majority Black.

Mueller may have stopped replying to Columbus and Moss Point, but a sales representative, John Flynn, was still pushing updated meters in Tupelo last June.

In an email to Chris Lewis, the local utility’s superintendent, he asked if the city wanted to “try some of our new meters.” Mr. Lewis said he would take five. Mr. Flynn said they come eight to a box.

Mr. Lewis responded: “Perfect!”

Irene Casado Sanchez contributed reporting. This article was reported in partnership with Big Local News at Stanford University.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=328531

Mississippi Today

1964: Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party was formed

April 26, 1964

Civil rights activists started the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party to challenge the state’s all-white regular delegation to the Democratic National Convention.

The regulars had already adopted this resolution: “We oppose, condemn and deplore the Civil Rights Act of 1964 … We believe in separation of the races in all phases of our society. It is our belief that the separation of the races is necessary for the peace and tranquility of all the people of Mississippi, and the continuing good relationship which has existed over the years.”

In reality, Black Mississippians had been victims of intimidation, harassment and violence for daring to try and vote as well as laws passed to disenfranchise them. As a result, by 1964, only 6% of Black Mississippians were permitted to vote. A year earlier, activists had run a mock election in which thousands of Black Mississippians showed they would vote if given an opportunity.

In August 1964, the Freedom Party decided to challenge the all-white delegation, saying they had been illegally elected in a segregated process and had no intention of supporting President Lyndon B. Johnson in the November election.

The prediction proved true, with white Mississippi Democrats overwhelmingly supporting Republican candidate Barry Goldwater, who opposed the Civil Rights Act. While the activists fell short of replacing the regulars, their courageous stand led to changes in both parties.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Mississippi River flooding Vicksburg, expected to crest on Monday

Warren County Emergency Management Director John Elfer said Friday floodwaters from the Mississippi River, which have reached homes in and around Vicksburg, will likely persist until early May. Elfer estimated there areabout 15 to 20 roads underwater in the area.

“We’re about half a foot (on the river gauge) from a major flood,” he said. “But we don’t think it’s going to be like in 2011, so we can kind of manage this.”

The National Weather projects the river to crest at 49.5 feet on Monday, making it the highest peak at the Vicksburg gauge since 2020. Elfer said some residents in north Vicksburg — including at the Ford Subdivision as well as near Chickasaw Road and Hutson Street — are having to take boats to get home, adding that those who live on the unprotected side of the levee are generally prepared for flooding.

“There are a few (inundated homes), but we’ve mitigated a lot of them,” he said. “Some of the structures have been torn down or raised. There are a few people that still live on the wet side of the levee, but they kind of know what to expect. So we’re not too concerned with that.”

The river first reached flood stage in the city — 43 feet — on April 14. State officials closed Highway 465, which connects the Eagle Lake community just north of Vicksburg to Highway 61, last Friday.

Elfer said the areas impacted are mostly residential and he didn’t believe any businesses have been affected, emphasizing that downtown Vicksburg is still safe for visitors. He said Warren County has worked with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Mississippi Emergency Management Agency to secure pumps and barriers.

“Everybody thus far has been very cooperative,” he said. “We continue to tell people stay out of the flood areas, don’t drive around barricades and don’t drive around road close signs. Not only is it illegal, it’s dangerous.”

NWS projects the river to stay at flood stage in Vicksburg until May 6. The river reached its record crest of 57.1 feet in 2011.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

With domestic violence law, victims ‘will be a number with a purpose,’ mother says

Joslin Napier. Carlos Collins. Bailey Mae Reed.

They are among Mississippi domestic violence homicide victims whose family members carried their photos as the governor signed a bill that will establish a board to study such deaths and how to prevent them.

Tara Gandy, who lost her daughter Napier in Waynesboro in 2022, said it’s a moment she plans to tell her 5-year-old grandson about when he is old enough. Napier’s presence, in spirit, at the bill signing can be another way for her grandson to feel proud of his mother.

“(The board) will allow for my daughter and those who have already lost their lives to domestic violence … to no longer be just a number,” Gandy said. “They will be a number with a purpose.”

Family members at the April 15 private bill signing included Ashla Hudson, whose son Collins, died last year in Jackson. Grandparents Mary and Charles Reed and brother Colby Kernell attended the event in honor of Bailey Mae Reed, who died in Oxford in 2023.

Joining them were staff and board members from the Mississippi Coalition Against Domestic Violence, the statewide group that supports shelters and advocated for the passage of Senate Bill 2886 to form a Domestic Violence Facility Review Board.

The law will go into effect July 1, and the coalition hopes to partner with elected officials who will make recommendations for members to serve on the board. The coalition wants to see appointees who have frontline experience with domestic violence survivors, said Luis Montgomery, public policy specialist for the coalition.

A spokesperson from Gov. Tate Reeves’ office did not respond to a request for comment Friday.

Establishment of the board would make Mississippi the 45th state to review domestic violence fatalities.

Montgomery has worked on passing a review board bill since December 2023. After an unsuccessful effort in 2024, the coalition worked to build support and educate people about the need for such a board.

In the recent legislative session, there were House and Senate versions of the bill that unanimously passed their respective chambers. Authors of the bills are from both political parties.

The review board is tasked with reviewing a variety of documents to learn about the lead up and circumstances in which people died in domestic violence-related fatalities, near fatalities and suicides – records that can include police records, court documents, medical records and more.

From each review, trends will emerge and that information can be used for the board to make recommendations to lawmakers about how to prevent domestic violence deaths.

“This is coming at a really great time because we can really get proactive,” Montgomery said.

Without a board and data collection, advocates say it is difficult to know how many people have died or been injured in domestic-violence related incidents.

A Mississippi Today analysis found at least 300 people, including victims, abusers and collateral victims, died from domestic violence between 2020 and 2024. That analysis came from reviewing local news stories, the Gun Violence Archive, the National Gun Violence Memorial, law enforcement reports and court documents.

Some recent cases the board could review are the deaths of Collins, Napier and Reed.

In court records, prosecutors wrote that Napier, 24, faced increased violence after ending a relationship with Chance Fabian Jones. She took action, including purchasing a firearm and filing for a protective order against Jones.

Jones’s trial is set for May 12 in Wayne County. His indictment for capital murder came on the first anniversary of her death, according to court records.

Collins, 25, worked as a nurse and was from Yazoo City. His ex-boyfriend Marcus Johnson has been indicted for capital murder and shooting into Collins’ apartment. Family members say Collins had filed several restraining orders against Johnson.

Johnson was denied bond and remains in jail. His trial is scheduled for July 28 in Hinds County.

He was a Jackson police officer for eight months in 2013. Johnson was separated from the department pending disciplinary action leading up to immediate termination, but he resigned before he was fired, Jackson police confirmed to local media.

Reed, 21, was born and raised in Michigan and moved to Water Valley to live with her grandparents and help care for her cousin, according to her obituary.

Kylan Jacques Phillips was charged with first degree murder for beating Reed, according to court records. In February, the court ordered him to undergo a mental evaluation to determine if he is competent to stand trial, according to court documents.

At the bill signing, Gandy said it was bittersweet and an honor to meet the families of other domestic violence homicide victims.

“We were there knowing we are not alone, we can travel this road together and hopefully find ways to prevent and bring more awareness about domestic violence,” she said.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days agoJim talks with Rep. Robert Andrade about his investigation into the Hope Florida Foundation

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days agoPrayer Vigil Held for Ronald Dumas Jr., Family Continues to Pray for His Return | April 21, 2025 | N

-

Mississippi Today6 days ago

Mississippi Today6 days ago‘Trainwreck on the horizon’: The costly pains of Mississippi’s small water and sewer systems

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed5 days agoTrump touts manufacturing while undercutting state efforts to help factories

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Texas News Feed5 days agoMeteorologist Chita Craft is tracking a Severe Thunderstorm Warning that's in effect now

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Virginia News Feed5 days agoTaking video of military bases using drones could be outlawed | Virginia

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed4 days agoFederal report due on Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina’s path to recognition as a tribal nation

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days agoAs country grows more polarized, America needs unity, the ‘Oklahoma Standard,’ Bill Clinton says