Mississippi Today

Belzoni to Rolling Fork to Greenville: One mom’s mission to get her son medical help after the tornadoes

Belzoni to Rolling Fork to Greenville: One mom’s mission to get her son medical help after the tornadoes

Tameka Myles was at work Friday evening when she got the call every mother dreads.

“You need to get here,” her neighbor in Rolling Fork said. “Jay is hurt pretty bad.”

Immediately, Myles got in her Nissan Maxima with a coworker and raced home, with one thing on her mind: her son.

Myles knew the weather was bad that night, but she assumed it would pass, as usual. She figured her 10-year-old son Gregory “Jay” Brady Jr. would be safe at her cousin’s house while she was at work at the Bumpers in Belzoni about an hour away.

Instead, her hometown was decimated.

An EF-4 tornado ripped through the Mississippi Delta on Friday night. At least 25 people died, and dozens more were injured. Gov. Tate Reeves issued a state of emergency Saturday morning.

“My city – my city is gone,” Rolling Fork Mayor Eldridge Walker told CNN Saturday morning. “But we are resilient and we are going to come back strong.”

That night, Myles drove down pitch black roads and through downed power lines, one hand permanently pressed down on her car horn. She couldn’t fathom the devastation around her in the place she had grown up.

On the way there, Myles got a call from another neighbor who had picked up her son and taken him to the Rolling Fork Motel.

“It was the only place that she could get to, because they had everything blocked off,” Myles said.

Myles arrived at the motel to see her son sprawled out on a bed, bleeding from his side.

“I knew that I couldn’t break down,” she said. “I had to get my baby some help.”

The neighbor had already tried to get her son admitted at the local hospital, Sharkey Issaquena Community Hospital – the only hospital in the county. But it was full, and later lost power and had to transfer its patients to other hospitals.

The rural hospital has been struggling to stay afloat and was, as of September, seeking a buyer. It has continued to lose money over the years, even after pooling its resources with other small hospitals to buy supplies at a discounted rate.

EMTs said they’d return for Jay after taking someone already in the ambulance to Greenville, but the neighbor, a certified nurse assistant, knew the boy couldn’t wait.

When Myles heard her son couldn’t get emergency medical help, she was dumbfounded.

Malary White, chief communications officer at the Mississippi Emergency Management Agency, said emergency responders were en route to assist survivors within minutes after the storm and ambulances were dispatched from across the state to Sharkey County.

But she conceded that medical resources were stretched.

“Let’s keep in mind we were dealing with a mass casualty situation,” she said.

“Can they do that?” Myles kept asking. Myles couldn’t understand why her son couldn’t get help. But one thing was clear — she had to take matters into her own hands.

Myles and her coworker picked up Jay and loaded him into her car, before calling Jay’s father. They met up with him, transferred Jay to his car in the backseat because it was larger, and they sped the 41 miles toward Greenville, the closest place Myles knew Jay would be able to receive medical attention.

On the way there, Jay’s father kept calling Myles, telling her that Jay was complaining he couldn’t breathe. Myles started crying. Her coworker begged Myles to let him drive, but she refused.

“We’re not stopping,” she said. “We’ve got to get to Greenville.”

As they rolled into Greenville at 10 p.m., Myles blew past five red stop lights. Her coworker hung his head out of the window, yelling at bystanders to get out of the way. When Myles spotted the Delta Regional Medical Center, all she could think was, “Thank God we made it.”

Twenty minutes later, Myles discovered that Jay had four fractured ribs, and one of his lungs was punctured.

Someone with a punctured lung runs the risk of fatal complications like cardiac arrest, respiratory failure, shock and death if not treated quickly.

He’d need to be put on oxygen and transferred to a larger hospital —nurses at Delta Health told Myles that the hospital didn’t have the equipment to help Jay.

Saturday morning, Jay was taken by helicopter to Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital in Memphis. Myles joined him at noon.

That night, Myles pulled the recliner close to Jay’s hospital bed. She put two of her braids in his hand before he fell asleep, and told him to yank if he needed help. Then she slept for the first time in more than 24 hours.

Jay has since been taken off oxygen and is breathing on his own. He’s still got tubes in his side, but he’s talking more and smiling, and Myles is relieved.

But she’s haunted by the possibilities of what might have happened if she didn’t have a car. She wonders how quickly they’d be able to get help if they didn’t live in rural Mississippi.

“My options were limited. I knew I had to do it myself,” Myles said. “I don’t really want to think about me not being able to help my son.”

She still has no idea how her son was injured. All Myles can find out about her cousin, who Jay was with during the tornado, is that he’s in critical condition at a hospital in Jackson.

It’s not clear when Jay will be discharged. Multiple times a day, he asks when they can go home. Myles hasn’t told him yet that their home doesn’t exist anymore. Their trailer and everything in it was destroyed.

And now, after her son couldn’t get the help he needed, Myles isn’t so sure that she wants to return home. Things are only set to get worse: One report puts a third of Mississippi’s rural hospitals at risk of closure, making it even harder to access health care.

“I think what I’m going to do is we’re going to move to a bigger area, where we’ve got support,” Myles said. “Where we can get help.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=228855

Mississippi Today

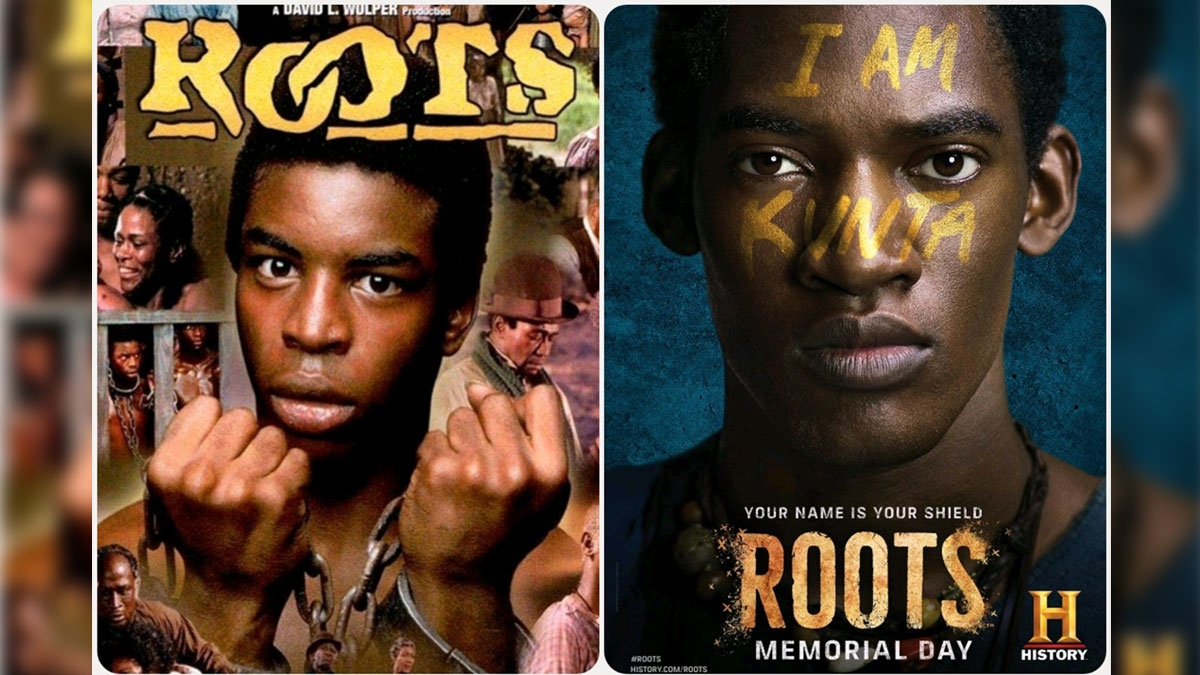

On this day in 1977, Alex Haley awarded Pulitzer for ‘Roots’

April 19, 1977

Alex Haley was awarded a special Pulitzer Prize for “Roots,” which was also adapted for television.

Network executives worried that the depiction of the brutality of the slave experience might scare away viewers. Instead, 130 million Americans watched the epic miniseries, which meant that 85% of U.S. households watched the program.

The miniseries received 36 Emmy nominations and won nine. In 2016, the History Channel, Lifetime and A&E remade the miniseries, which won critical acclaim and received eight Emmy nominations.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Speaker White wants Christmas tree projects bill included in special legislative session

House Speaker Jason White sent a terse letter to Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann on Thursday, saying House leaders are frustrated with Senate leaders refusing to discuss a “Christmas tree” bill spending millions on special projects across the state.

The letter signals the two Republican leaders remain far apart on setting an overall $7 billion state budget. Bickering between the GOP leaders led to a stalemate and lawmakers ending their regular 2025 session without setting a budget. Gov. Tate Reeves plans to call them back into special session before the new budget year starts July 1 to avoid a shutdown, but wants them to have a budget mostly worked out before he does so.

White’s letter to Hosemann, which contains words in all capital letters that are underlined and italicized, said that the House wants to spend cash reserves on projects for state agencies, local communities, universities, colleges, and the Mississippi Department of Transportation.

“We believe the Senate position to NOT fund any local infrastructure projects is unreasonable,” White wrote.

The speaker in his letter noted that he and Hosemann had a meeting with the governor on Tuesday. Reeves, according to the letter, advised the two legislative leaders that if they couldn’t reach an agreement on how to disburse the surplus money, referred to as capital expense money, they should not spend any of it on infrastructure.

A spokesperson for Hosemann said the lieutenant governor has not yet reviewed the letter, and he was out of the office on Thursday working with a state agency.

“He is attending Good Friday services today, and will address any correspondence after the celebration of Easter,” the spokesperson said.

Hosemann has recently said the Legislature should set an austere budget in light of federal spending cuts coming from the Trump administration, and because state lawmakers this year passed a measure to eliminate the state income tax, the source of nearly a third of the state’s operating revenue.

Lawmakers spend capital expense money for multiple purposes, but the bulk of it — typically $200 million to $400 million a year — goes toward local projects, known as the Christmas Tree bill. Lawmakers jockey for a share of the spending for their home districts, in a process that has been called a political spoils system — areas with the most powerful lawmakers often get the largest share, not areas with the most needs. Legislative leaders often use the projects bill as either a carrot or stick to garner votes from rank and file legislators on other issues.

A Mississippi Today investigation last year revealed House Ways and Means Chairman Trey Lamar, a Republican from Sentobia, has steered tens of millions of dollars in Christmas tree spending to his district, including money to rebuild a road that runs by his north Mississippi home, renovate a nearby private country club golf course and to rebuild a tiny cul-de-sac that runs by a home he has in Jackson.

There is little oversight on how these funds are spent, and there is no requirement that lawmakers disburse the money in an equal manner or based on communities’ needs.

In the past, lawmakers borrowed money for Christmas tree bills. But state coffers have been full in recent years largely from federal pandemic aid spending, so the state has been spending its excess cash. White in his letter said the state has “ample funds” for a special projects bill.

“We, in the House, would like to sit down and have an agreement with our Senate counterparts on state agency Capital Expenditure spending AND local projects spending,” White wrote. “It is extremely important to our agencies and local governments. The ball is in your court, and the House awaits your response.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Mississippi Today

Advocate: Election is the chance for Jackson to finally launch in the spirit of Blue Origin

Editor’s note: This essay is part of Mississippi Today Ideas, a platform for thoughtful Mississippians to share fact-based ideas about our state’s past, present and future. You can read more about the section here.

As the world recently watched the successful return of Blue Origin’s historic all-women crew from space, Jackson stands grounded. The city is still grappling with problems that no rocket can solve.

But the spirit of that mission — unity, courage and collective effort — can be applied right here in our capital city. Instead of launching away, it is time to launch together toward a more just, functioning and thriving Jackson.

The upcoming mayoral runoff election on April 22 provides such an opportunity, not just for a new administration, but for a new mindset. This isn’t about endorsements. It’s about engagement.

It’s a moment for the people of Jackson and Hinds County to take a long, honest look at ourselves and ask if we have shown up for our city and worked with elected officials, instead of remaining at odds with them.

It is time to vote again — this time with deeper understanding and shared responsibility. Jackson is in crisis — and crisis won’t wait.

According to the U.S. Census projections, Jackson is the fastest-shrinking city in the United States, losing nearly 4,000 residents in a single year. That kind of loss isn’t just about numbers. It’s about hope, resources, and people’s decision to give up rather than dig in.

Add to that the long-standing issues: a crippled water system, public safety concerns, economic decline and a sense of division that often pits neighbor against neighbor, party against party and race against race.

Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba has led through these storms, facing criticism for his handling of the water crisis, staffing issues and infrastructure delays. But did officials from the city, the county and the state truly collaborate with him or did they stand at a distance, waiting to assign blame?

On the flip side, his runoff opponent, state Sen. John Horhn, who has served for more than three decades, is now seeking to lead the very city he has represented from the Capitol. Voters should examine his legislative record and ask whether he used his influence to help stabilize the administration or only to position himself for this moment.

Blaming politicians is easy. Building cities is hard. And yet that is exactly what’s needed. Jackson’s future will not be secured by a mayor alone. It will take so many of Jackson’s residents — voters, business owners, faith leaders, students, retirees, parents and young people — to move this city forward. That’s the liftoff we need.

It is time to imagine Jackson as a capital city where clean, safe drinking water flows to every home — not just after lawsuits or emergencies, but through proactive maintenance and funding from city, state and federal partnerships. The involvement of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in the effort to improve the water system gives the city leverage.

Public safety must be a guarantee and includes prevention, not just response, with funding for community-based violence interruption programs, trauma services, youth job programs and reentry support. Other cities have done this and it’s working.

Education and workforce development are real priorities, preparing young people not just for diplomas but for meaningful careers. That means investing in public schools and in partnerships with HBCUs, trade programs and businesses rooted right here.

Additionally, city services — from trash collection to pothole repair — must be reliable, transparent and equitable, regardless of zip code or income. Seamless governance is possible when everyone is at the table.

Yes, democracy works because people show up. Not just to vote once, but to attend city council meetings, serve on boards, hold leaders accountable and help shape decisions about where resources go.

This election isn’t just about who gets the title of mayor. It’s about whether Jackson gets another chance at becoming the capital city Mississippi deserves — a place that leads by example and doesn’t lag behind.

The successful Blue Origin mission didn’t happen by chance. It took coordinated effort, diverse expertise and belief in what was possible. The same is true for this city.

We are not launching into space. But we can launch a new era marked by cooperation over conflict, and by sustained civic action over short-term outrage.

On April 22, go vote. Vote not just for a person, but for a path forward because Jackson deserves liftoff. It starts with us.

Pauline Rogers is a longtime advocate for criminal justice reform and the founder of the RECH Foundation, an organization dedicated to supporting formerly incarcerated individuals as they reintegrate into society. She is a Transformative Justice Fellow through The OpEd Project Public Voices Fellowship.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

-

Mississippi Today6 days ago

Mississippi Today6 days agoLawmakers used to fail passing a budget over policy disagreement. This year, they failed over childish bickering.

-

Mississippi Today6 days ago

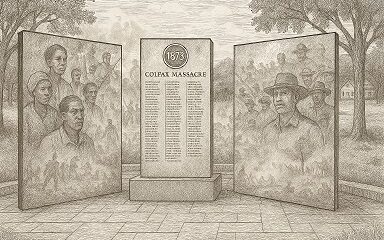

Mississippi Today6 days agoOn this day in 1873, La. courthouse scene of racial carnage

-

Local News7 days ago

Local News7 days agoAG Fitch and Children’s Advocacy Centers of Mississippi Announce Statewide Protocol for Child Abuse Response

-

Local News6 days ago

Local News6 days agoSouthern Miss Professor Inducted into U.S. Hydrographer Hall of Fame

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days agoFoley man wins Race to the Finish as Kyle Larson gets first win of 2025 Xfinity Series at Bristol

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days agoFederal appeals court upholds ruling against Alabama panhandling laws

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days agoSevere weather has come and gone for Central Florida, but the rain went with it

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days agoBellingrath Gardens previews its first Chinese Lantern Festival