Mississippi Today

Ballot initiative death, coming soon to a campaign ad near you

Ballot initiative death, coming soon to a campaign ad near you

Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann and any state senator with an opponent for reelection this year can expect to field lots of questions and campaign-ad jabs about the Senate killing a measure to restore voters’ right to sidestep the Legislature and put measures on a statewide ballot.

Senate Accountability Efficiency and Transparency Chairman John Polk, R-Hattiesburg, let a ballot initiative measure die without a vote. A last-minute Hail Mary attempt to revive it led by Hosemann in the final days of this year’s legislative session failed.

READ MORE: Senate kills Mississippi ballot initiative without a vote

Now, the soonest a right guaranteed Mississippians in the state constitution could be restored would be November of 2024 — provided lawmakers next year pass a measure and put it before voters for ratification in the federal elections.

“I was for ballot initiative and I didn’t get it,” Hosemann said on Monday, after lawmakers ended the 2023 legislative session on Saturday. But many political observers, and Hosemann’s primary challenger Sen. Chris McDaniel, lay at least some of the blame on Hosemann for it failing for the second year in a row. Hosemann routed the bill to Polk’s committee again, knowing Polk himself is against reinstating the initiative, and that he would play hardball demanding restrictions on its use in any negotiations with the House.

In a statement, McDaniel said: “Delbert Hosemann chose yet again to silence the voices of Mississippians and protect his own power by obstructing our ballot initiative process. Delbert’s actions are both disgraceful and unconstitutional.”

Democratic lawmakers slammed the GOP statehouse leadership as “out of step … with each other and the vast majority of Mississippians — including their own voters.”

Brandon Presley, Democratic challenger to Gov. Tate Reeves, is even trying to make hay of the issue in gubernatorial race, saying, “Tate Reeves and his allies in the Legislature didn’t lift a finger to restore the people’s right to petition their government because the status quo gives them and their lobbyist pals more power.” He said that if he were governor he would have pushed lawmakers to pass it, and would call the Legislature back into special session to restore the right after it failed.

Hosemann, when the measure died, said he was for it but he lets his Senate chairman make their own decisions. But then he pushed the Senate to take the relatively rare step of suspending rules and deadlines with a two-thirds vote to allow it to be revived in the eleventh hour of the session. This vote passed, but it would have required the House to do likewise, then a new bill would have to be introduced, agreements haggled out, then passed by both chambers.

READ MORE: Senate, in 11th hour, tries to revive ballot initiative measure it previously killed

House Speaker Philip Gunn on Monday said Hosemann’s last-ditch effort with the ballot initiative was too little, too late. He said having an agreement would have been worth suspending rules to pass a bill, but the Senate was only proposing another counter offer and wanting to haggle more, and lawmakers were having to focus on passing a state budget and finishing the session.

“We tried,” Gunn said. “The House passed it two years in a row. Our position has been pretty well stated. What we passed twice was pretty close to what it was originally, and the Senate was not willing to take that … If they wanted to do the initiative they had every opportunity.”

The main sticking point — besides the Senate chairman in charge of handling the initiative being against it — between the House and Senate was the number of signatures of registered voters required to put a measure on a statewide ballot. The Senate’s original position would have required at least 240,000 signatures. The House version would have required about 106,000, nearer the previous threshold required for the last 30 years.

The Senate’s last-minute counter offer, Gunn said, would have required more than 150,000 signatures, a figure he said was still too high.

Otherwise, both chambers’ proposals would have greatly restricted voters’ right to ballot initiative compared to the process that had been in place since 1992. Under both, the Legislature by a simple majority vote could change or repeal an initiative approved by the electorate.

Recent polls have shown Mississippi voters across the spectrum want their right to put issues directly on a statewide ballot restored. AMississippi Today/Siena College pollshowed 72% favor reinstating ballot initiative, with 12% opposed and 16% either don’t know or have no opinion. Restoring the right garnered a large majority among Democrats, Republicans, independents and across all demographic, geographic and income lines.

The state Supreme Court nullified Mississippi’s ballot initiative in 2021, in a ruling on a medical marijuana initiative voters had overwhelmingly passed, taking matters in hand after lawmakers dickered over the issue for years. Legislative leaders, including Gunn and Hosemann, vowed they would restore the right to voters, fix the legal glitches that prompted the court to rule it invalid.

READ MORE: Is ballot initiative a ‘take your picture off the wall’ issue for lawmakers?

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

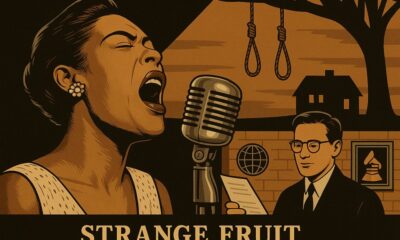

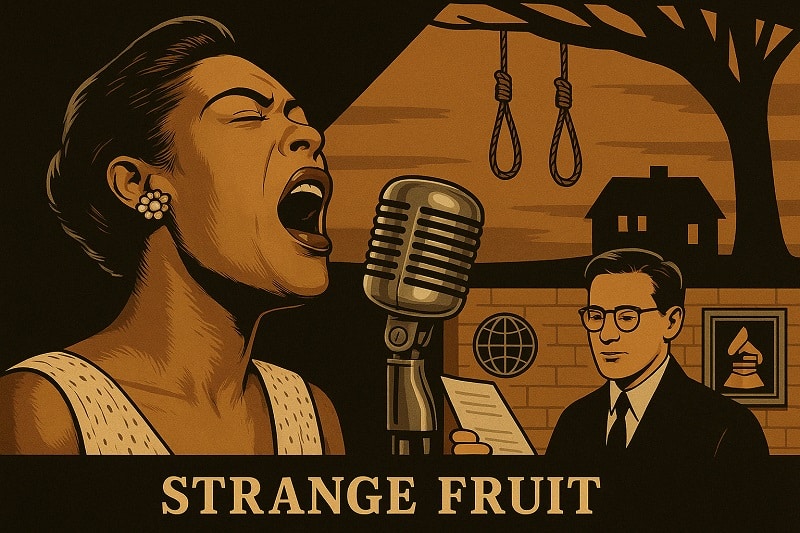

On this day in 1939, Billie Holiday recorded ‘Strange Fruit’

April 20, 1939

Legendary jazz singer Billie Holiday stepped into a Fifth Avenue studio and recorded “Strange Fruit,” a song written by Jewish civil rights activist Abel Meeropol, a high school English teacher upset about the lynchings of Black Americans — more than 6,400 between 1865 and 1950.

Meeropol and his wife had adopted the sons of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who were orphaned after their parents’ executions for espionage.

Holiday was drawn to the song, which reminded her of her father, who died when a hospital refused to treat him because he was Black. Weeks earlier, she had sung it for the first time at the Café Society in New York City. When she finished, she didn’t hear a sound.

“Then a lone person began to clap nervously,” she wrote in her memoir. “Then suddenly everybody was clapping.”

The song sold more than a million copies, and jazz writer Leonard Feather called it “the first significant protest in words and music, the first unmuted cry against racism.”

After her 1959 death, both she and the song went into the Grammy Hall of Fame, Time magazine called “Strange Fruit” the song of the century, and the British music publication Q included it among “10 songs that actually changed the world.”

David Margolick traces the tune’s journey through history in his book, “Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday and the Biography of a Song.” Andra Day won a Golden Globe for her portrayal of Holiday in the film, “The United States vs. Billie Holiday.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Mississippians are asked to vote more often than people in most other states

Not long after many Mississippi families celebrate Easter, they will be returning to the polls to vote in municipal party runoff elections.

The party runoff is April 22.

A year does not pass when there is not a significant election in the state. Mississippians have the opportunity to go to the polls more than voters in most — if not all — states.

In Mississippi, do not worry if your candidate loses because odds are it will not be long before you get to pick another candidate and vote in another election.

Mississippians go to the polls so much because it is one of only five states nationwide where the elections for governor and other statewide and local offices are held in odd years. In Mississippi, Kentucky and Louisiana, the election for governor and other statewide posts are held the year after the federal midterm elections. For those who might be confused by all the election lingo, the federal midterms are the elections held two years after the presidential election. All 435 members of the U.S. House and one-third of the membership of the U.S. Senate are up for election during every midterm. In Mississippi, there also are important judicial elections that coincide with the federal midterms.

Then the following year after the midterms, Mississippians are asked to go back to the polls to elect a governor, the seven other statewide offices and various other local and district posts.

Two states — Virginia and New Jersey — are electing governors and other state and local officials this year, the year after the presidential election.

The elections in New Jersey and Virginia are normally viewed as a bellwether of how the incumbent president is doing since they are the first statewide elections after the presidential election that was held the previous year. The elections in Virginia and New Jersey, for example, were viewed as a bad omen in 2021 for then-President Joe Biden and the Democrats since the Republican in the swing state of Virginia won the Governor’s Mansion and the Democrats won a closer-than-expected election for governor in the blue state of New Jersey.

With the exception of Mississippi, Louisiana, Kentucky, Virginia and New Jersey, all other states elect most of their state officials such as governor, legislators and local officials during even years — either to coincide with the federal midterms or the presidential elections.

And in Mississippi, to ensure that the democratic process is never too far out of sight and mind, most of the state’s roughly 300 municipalities hold elections in the other odd year of the four-year election cycle — this year.

The municipal election impacts many though not all Mississippians. Country dwellers will have no reason to go to the polls this year except for a few special elections. But in most Mississippi municipalities, the offices for mayor and city council/board of aldermen are up for election this year.

Jackson, the state’s largest and capital city, has perhaps the most high profile runoff election in which state Sen. John Horhn is challenging incumbent Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba in the Democratic primary.

Mississippi has been electing its governors in odd years for a long time. The 1890 Mississippi Constitution set the election for governor for 1895 and “every four years thereafter.”

There is an argument that the constant elections in Mississippi wears out voters, creating apathy resulting in lower voter turnout compared to some other states.

Turnout in presidential elections is normally lower in Mississippi than the nation as a whole. In 2024, despite the strong support for Republican Donald Trump in the state, 57.5% of registered voters went to the polls in Mississippi compared to the national average of 64%, according to the United States Elections Project.

In addition, Mississippi Today political reporter Taylor Vance theorizes that the odd year elections for state and local officials prolonged the political control for Mississippi Democrats. By 1948, Mississippians had started to vote for a candidate other than the Democrat for president. Mississippians began to vote for other candidates — first third party candidates and then Republicans — because of the national Democratic Party’s support of civil rights.

But because state elections were in odd years, it was easier for Mississippi Democrats to distance themselves from the national Democrats who were not on the ballot and win in state and local races.

In the modern Mississippi political environment, though, Republicans win most years — odd or even, state or federal elections. But Democrats will fare better this year in municipal elections than they do in most other contests in Mississippi, where the elections come fast and often.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Mississippi Today

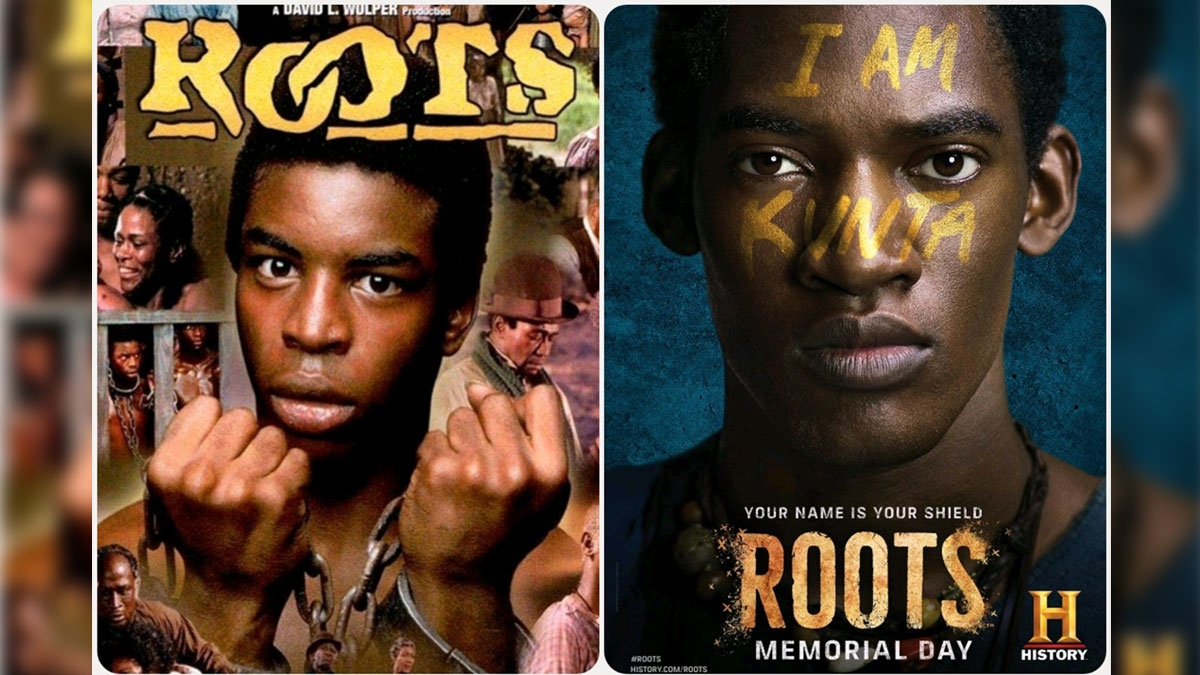

On this day in 1977, Alex Haley awarded Pulitzer for ‘Roots’

April 19, 1977

Alex Haley was awarded a special Pulitzer Prize for “Roots,” which was also adapted for television.

Network executives worried that the depiction of the brutality of the slave experience might scare away viewers. Instead, 130 million Americans watched the epic miniseries, which meant that 85% of U.S. households watched the program.

The miniseries received 36 Emmy nominations and won nine. In 2016, the History Channel, Lifetime and A&E remade the miniseries, which won critical acclaim and received eight Emmy nominations.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days agoFoley man wins Race to the Finish as Kyle Larson gets first win of 2025 Xfinity Series at Bristol

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days agoFederal appeals court upholds ruling against Alabama panhandling laws

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed5 days agoFDA warns about fake Ozempic, how to spot it

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed5 days agoAbandoned property causing issues in Pine Lawn, neighbor demands action

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed3 days ago

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed3 days agoThursday April 17, 2025 TIMELINE: Severe storms Friday

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Virginia News Feed4 days agoLieutenant governor race heats up with early fundraising surge | Virginia

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days agoTwo dead, 9 injured after shooting at Conway park | What we know

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed3 days ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed3 days agoDrivers brace for upcoming I-70 construction, slowdowns