Douglas Sacha/moment via Getty Images

Kerby Goff, Rice University; Eric Silver, Penn State, and John Iceland, Penn State

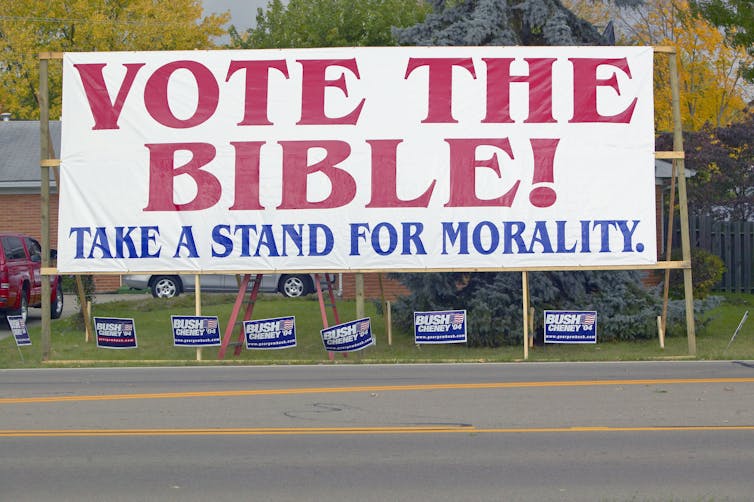

The concept of Christian nationalism has taken center stage in many Americans’ minds as either the greatest threat to democracy or its only savior.

Political scientist Eric McDaniel defines Christian nationalism as the belief that the United States was founded to be a Christian nation. “In this view,” according to McDaniel, “America can be governed only by Christians, and the country’s mission is directed by a divine hand.” Why does the idea resonate with some but alarm others?

Scholars often portray Christian nationalism as rooted in a deep-seated desire to exclude non-Christians and people of color from American society. Historians point to a persistent link between racism and Christian nationalism among white Americans throughout U.S. history.

White Christians, however, are not the only ones sympathetic to Christian nationalist ideas. Nearly 40% of Black Protestants and 55% of Hispanic Protestants agree with statements such as “being Christian is an important part of being truly American.” Interestingly, over one-third of Muslims agree that the U.S. government should promote Christian moral values but not make it the official religion.

Many who reject Christian nationalism do so because it seems to privilege those white Christian Americans who would like to make conservative Christianity the United States’ official religion. Conversely, supporters argue that the future of the U.S. depends upon loyalty to God and to staying true to the country’s Christian past. They contend that since the nation’s founding, a Christian influence in government and societal institutions such as education and health care has been and remains essential to sustaining religious, political and economic stability.

While racial, religious and political tribalism appear to influence who supports and who rejects Christian nationalism, our own research suggests there are other factors at play, specifically moral differences. We set out to understand the role that different moral values play in shaping support for and opposition to Christian nationalism.

Our study drew on the most influential social science approach to understanding moral values: moral foundations theory.

Moral differences

Moral foundations theory states that humans evolved to possess six primary moral intuitions that shape moral judgments – care for the vulnerable, fairness in how people are treated, loyalty to in-groups, respect for authority, reverence for the sacred, and the safeguarding of individual liberty.

A vast amount of research finds that liberals endorse the first two foundations, care and fairness, but score lower on the rest.

Conservatives, on the other hand, tend to score equally on all six foundations. This suggests their moral judgments often involve balancing a desire to be compassionate with a desire to safeguard the stability of the social order.

Moral foundations theory has been used extensively by social scientists to study hot-button issues such as crime control, policing, vaccine resistance, immigration, same-sex marriage, abortion and more.

For example, research finds that prioritizing care for the vulnerable, which is most pronounced among liberals, is linked to reduced acceptance of police use of force. Conservatives, who also value respect for authority, often favor “law and order” even when it involves use of force.

What our research found

selimaksan/E+ via Getty images.

With moral foundations theory as our guide, we analyzed Christian nationalism using a 2021 national survey of 1,125 U.S. adults conducted by YouGov, a global opinion research organization. We measured respondents’ moral foundations with the moral foundations questionnaire, which has been used extensively by researchers across numerous academic disciplines.

To measure Christian nationalism, we asked respondents whether they agreed with six questions, such as whether the federal government should declare the United States a Christian nation, advocate Christian values, allow prayer in public schools and allow religious symbols in public spaces, to list a few.

What we found surprised us.

Support for Christian nationalism was most strongly linked to the moral foundations of loyalty, sanctity and liberty, but not to the authority foundation. We expected Christian nationalism to appeal to individuals who are enamored of authority, providing a rationale to their support for authoritarian leaders. But in our study, respect for authority did not distinguish those who supported Christian nationalism from those who opposed it.

We also found that support for Christian nationalism was linked to having a weaker fairness foundation. But it was not related to the strength of one’s care foundation.

We conclude that differences over Christian nationalism emerge not because some people care about the harm Christian nationalism could bring to non-Christian Americans, while others don’t. Rather, our findings suggest that those who support Christian nationalism do so because they are more sensitive to violations of loyalty, sanctity and liberty, and less sensitive to violations of fairness.

Our findings also revealed that support for Christian nationalism isn’t merely about racism or being ultrareligious, as critics often suggest. We accounted for endorsements of anti-Black stereotypes and religiosity. Yet, moral foundations remained the best predictors of Christian nationalist beliefs, even after taking into account these critical variables.

2 moral approaches to Christianity in the US

The Christian nationalism scale we and others have used combines several different beliefs about Christianity’s role in society. So we also examined how each of the six items in our Christian nationalism scale related to each of the six moral foundations. We found two important patterns.

Joe Sohm/Visions of America/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

First, we found that the Christian nationalist desire to bring church and state closer together was most prominent among those with strong loyalty and sanctity foundations and a weak fairness foundation. This means that people who advocate for a Christian state largely do so out of loyalty – specifically, loyalty to God – and out of a desire to adhere to God’s requirements for society, as they understand them.

In line with this, support is also linked to a desire to protect the sanctity of the nation’s Christian heritage. Those who oppose bringing church and state closer together do so out of a sense that such a union would be unfair.

Second, we found that the desire to allow prayer in schools and religious symbols in public spaces was strongest among those with pronounced liberty and sanctity moral foundations. This likely means that people who favor public religious expression, but not a union of church and state, do so because they see individual religious expression as a sacred national ideal.

All in all, our study shows that support for or opposition to Christian nationalism is not merely due to religious, political or racial identities and prejudices, as many believe, but is rather due to entrenched moral differences between the two camps.

Building solidarity through diverse moral concerns

Moral divides are not necessarily impassable. It’s possible that understanding these diverging moral concerns may help build bridges between those who are sympathetic to and those who are skeptical toward Christian nationalism.

America’s founders conceived of fairness and liberty as central to a democratic society. And these values have fueled loyalty to a robust national identity ever since.

Our research suggests that the controversy surrounding Christian nationalism is driven not by a lack of moral concern by sympathizers or critics but by their different moral priorities. We believe that understanding such differences as morally rooted can open the door for mutual understanding and productive debate.![]()

Kerby Goff, Associate Director of Research at the Boniuk Institute for the Study and Advancement of Religious Tolerance, Rice University; Eric Silver, Professor of Sociology & Criminology, Penn State, and John Iceland, Professor of Sociology and Demography, Penn State

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.