Mississippi Today

As health infrastructure shrinks, a daughter of the Delta cares for her community

As health infrastructure shrinks, a daughter of the Delta cares for her community

To reach Gunnison, Mississippi, from Cleveland, the quickest path – though not the route with the best-paved streets – takes you off Highway 8, down miles of narrow roads slicing through some of the most fertile land on earth. In early December, the fields are still but not empty. Silvery water pools in gashes in the dirt, and cardinals settle on shoots of electric green gleaming in the gray light of winter.

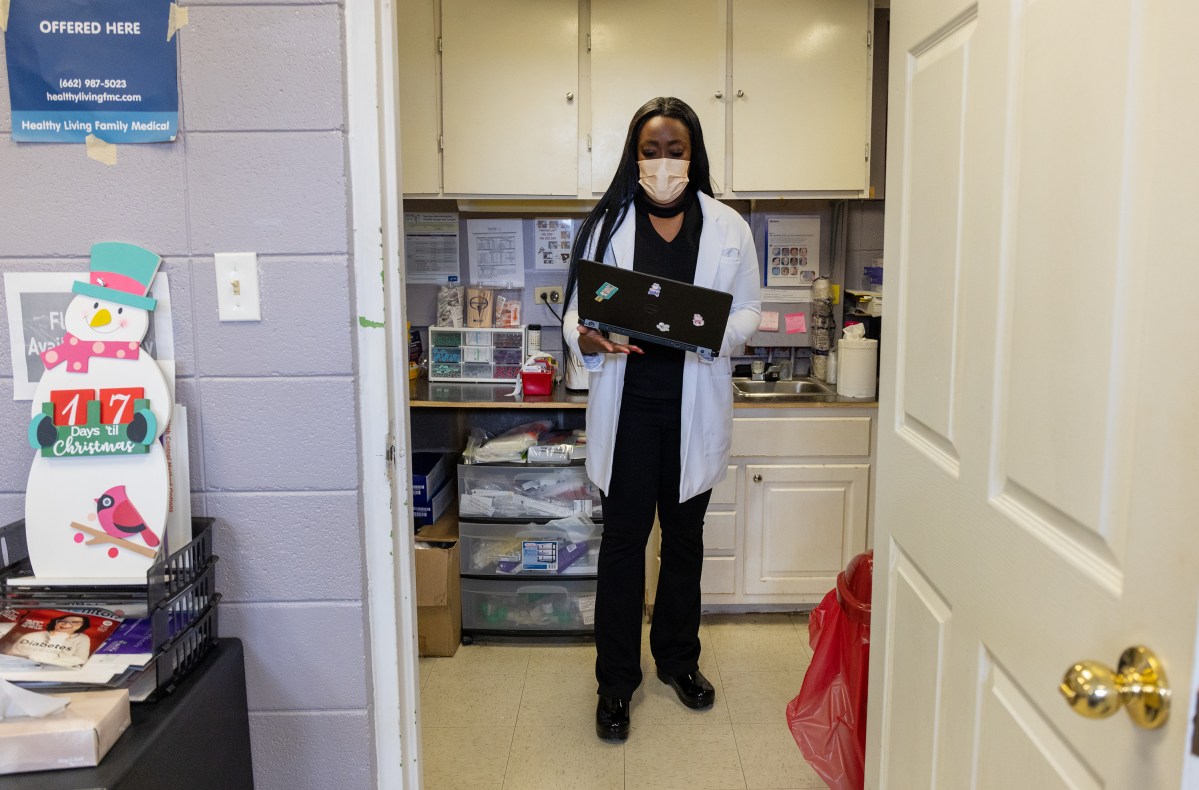

When you reach Highway 1, you’ve arrived in Gunnison, with a population of 425 and only two businesses: a gas station and Healthy Living Family Medical Clinic, opened by Gunnison native Wyconda Thomas in 2019. The squat brick building is decorated for the season, with a wreath on the door and letters out front spelling “Merry Christmas.”

When Thomas decided to open her own practice, she chose the place where she saw the greatest need, which also happened to be the community that raised her.

Despite the town’s small population, the clinic is full every day.

“The statistics– it pointed to these areas,” Thomas said. “The Delta, the lack of resources– if you look at who suffers the most, it’s always these areas. That’s the place you should be treating.”

No region of the state has been harder hit by the decimation of Mississippi’s health infrastructure than the Delta. Kings Daughters Hospital in Greenville closed in 2005, and Patient’s Choice Medical Center in Belzoni followed in 2013. Now, Greenwood-Leflore Hospital is scrambling to find funding to stay open through the legislative session, when it hopes to persuade lawmakers to help.

Even if the money comes through, there is no long-term plan to ensure Delta residents have access to health care. The predominantly Black region is one of the poorest in the country, and like the state as a whole, it has high rates of diabetes, hypertension and heart disease.Earlier this year, state health officer Dr. Daniel Edney said the region’s health infrastructure is “very fragile” and six Delta hospitals are at risk of closure.

“No one’s coming to the rescue,” he said.

No one, that is, except for Thomas and people like her: Delta natives who have chosen to open their own small clinics close to home. People like Mary Williams, who runs Urgent and Primary Care of Clarksdale; Juliet Thomas, Antoinette Roby and Desiree Norwood of the mobile clinic Plan A; and Nora Gough-Davis, who operates clinics in Shaw and Drew.

They face policies that seem almost designed to punish them for trying. Nurse practitioners are reimbursed by Medicaid just 85% of what physicians receive for providing the same services. State regulations require them to have a collaborating physician, to whom they must pay a monthly fee that can reach over $1,000. The state’s failure to expand Medicaid means more of their patients lack insurance, and they may never see a penny for treating them.

“You have to give yourself,” said Gough-Davis, who trained Thomas and 25 other Delta nurse practitioners at her clinics. “It’s really like community service. We have patients with low, low health literacy. So our typical visit is going to require much more education than a visit with someone who doesn’t have health literacy issues. Education takes time.”

And payment structures don’t account for that time.

“It never comes close” to full compensation, Gough-Davis said of the typical reimbursement.

Owning her own practice, Thomas has had to learn how to handle paperwork and billing and dealing with reimbursement from Medicaid and insurance companies. She works from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. most days, and spends weekends and evenings attending trainings and seminars. She sees everything from the flu and COVID-19 to anxiety and depression to birth control requests.

WIth the health department presence in Bolivar County shrinking and hospitals closing, clinics like Healthy Living are under pressure.

“The struggles are there,” she said. “Everything is being put onto family practice now.”

And yet Thomas struggles to imagine working anywhere else.

“The people here get me and I get them,” she said. “It’s rewarding to make a difference and to do this. I feel like I have God’s favor because of that.”

‘A personal connection to her patients’

Just before 9 a.m. on a recent Thursday, Thomas prepared to see her first patient of the day: a 3-year-old boy at the clinic for a well-child exam.

She wore black scrubs, with a matching scarf and shiny shoes, and a tidy red manicure. The clinic’s rooms radiated the same warmth and cheerful competence that she did: In the lobby, posters advertise free sports physicals and family planning services. A Christmas tree was decorated with hot pink ornaments.

Clutching a clipboard, Thomas walked into the first exam room to see her patient, accompanied by his mom and grandfather.

“Come on, hop up here,” she said to him, gesturing to the table. “I think he might need some help.”

She lifted him up and he sat calmly on the table, his hands folded in his lap and his sneaker-clad feet dangling several feet off the floor.

Thomas told his family that he needed to be in a booster seat and wearing a helmet when riding a bike. She confirmed he had recently seen a dentist, and would need a vision screen today.

“How’s his diet?” Thomas asked. “Does he eat a lot of foods like rice, cereal, cheeseburgers?”

“That’s about the only thing he’ll eat,” his mom answered.

Thomas laughed. She checked the boy’s ears. He gazed calmly around the room, never fidgeting or whining.

“You such a good little patient!” she exclaimed.

She told his family that he had some fluid in his ears, so she would send a prescription over to their pharmacy.

Then her time with the boy was over. The visit hadn’t been complicated, but Thomas had been able to confirm the 3-year-old was healthy and growing well, and his vision was good – a particularly important finding as he approached kindergarten, which most Mississippi kids reach without ever having had a developmental screening.

A few hours later, a 57-year-old woman named Arlesia Mobley sat in a different exam room. She complained of a headache and dizziness.

“Been around anybody sick?” Thomas asked.

“My grandbaby,” Mobley said. “She had the flu.”

Thomas checked her ears and saw fluid, which she explained was probably causing Mobley’s dizziness. She asked a nurse to conduct a flu swab but went ahead and ordered Tamiflu for her patient. She advised her to drink plenty of fluids, eat chicken noodle soup, and rest as much as possible.

A few days later, Mobley said she was feeling better, but still drained.

She had had to find a new doctor earlier this year because of her insurance. She lives in Rosedale, so Thomas was close by. She already feels like Thomas knows her.

“When she step into the room, she’s got that smile,” Mobley said later. “When she pass by you and you (are) sitting out in the waiting room, she got that smile. That makes me feel good, ‘cause I mean most doctors… especially in the waiting room, their mind wouldn’t be on you nowhere. But it seem like she got a personal connection to her patients.”

Opening a clinic in her hometown

Thomas is a daughter of the Delta, raised in Gunnison and Rosedale. Her parents both coached basketball, and she grew up in the gym. She was a star player at West Bolivar High School and then played for Delta State.

Her mom and dad, both Bolivar County natives, too, had high expectations for their daughter.

“When she was growing up, she couldn’t bring no C’s into my house,” said her mother, Will Ethel Hall. “I don’t want nothing but A’s, but we’ll talk about a B, because you was playing sports and maybe you didn’t get it that way. No C’s were allowed, and she knew that.”

“I was real hard on her,” said her father, Willie Thomas, who coached her at West Bolivar.

A few weeks ago, he ran into a woman in the store who was remembering how he had pushed his daughter. Thomas told her that looking back, he felt it had been too much, and he would do things differently if he could.

“She said, ‘Look how she turned out,’” Thomas said. “I said, ‘You right. I’d do it the same.’”

After college, she spent a year teaching biology before deciding she wanted to go into nursing and going back to school. She knew she’d like to open her own practice eventually, so she made a point of working in as many areas as she could – postpartum care, pediatrics, nursery, neonatal intensive care unit, home health and intensive care.

“You own your own practice in the Delta, you gotta be everything – resources are very, very limited, you know,” she said.

The Greenville NICU where Thomas trained closed earlier this year, leaving the Delta with no NICUs at all.

As soon as Thomas became a nurse practitioner in 2015, she started working on plans to open her own clinic. Her grandfather had owned the little building in Gunnison that had once been a county health facility, and the family left it to her for her business.

When she approached Gunnison leaders about opening a clinic there, they were elated.

“Our area is really underprivileged, and we just needed a clinic here in town to help our citizens,” said Mayor Frances Ward, who has known Thomas since she was born. “A lot of them don’t have transportation, and they had to pay people to carry them to Cleveland to the doctor. It’s really a blessing that she is here. And we’re very proud of her being from Gunnison, to come back and help her fellow people.”

Thomas opened Healthy Living on Jan. 2, 2019.

Gunnison residents like 70-year-old Ruby Hall, who works for Thomas as a nurse at the school-based clinics she runs in Rosedale, can’t recall a doctor or nurse coming back to the town in the last 60 years.

Tina Highsmith, executive director of the Mississippi Association of Nurse Practitioners, said that’s a common trajectory for Mississippians in their field.

“Even though I had moved to several other parts of the state, when I came back to open a clinic it was in my hometown,” she said. “Those NPs have already established relationships… And so the patients know them, they trust them.”

And Thomas knows her patients, often personally as well as through her work. That’s part of what drives her.

Her mother remembers missed lunch appointments because the clinic was so busy, and detours during drives to check up on patients at their homes or drop off medicine.

“It’s just a tie that I have here,” Thomas said. “They need me so bad. At least I feel like they do. That makes me stay here.

From 13 county health department clinics to one

At the only other business in Gunnison, Bassie’s Service Station, Charlette Brady slices cold cuts, makes sandwiches and rings up bottles of soda and beer.

“Really don’t much go on here,” she said.

The opening of Thomas’s clinic was a rare event. Before, Brady and her children traveled to Cleveland for doctors’ appointments. Now, the whole family goes to Healthy Living.

Inside the lobby of the clinic, a plaque commemorates the building’s history. Preserved in the cinderblock wall, the black sign with silver lettering reads: “Bolivar County Branch Health Center. Gunnison, Mississippi. 1960.”

The plaque also hints at how rural Mississippi’s health care resources have shrunk over the last several decades, because the Gunnison county health department site closed sometime in the 1980s. Before Thomas opened her clinic in 2019, it served as a polling location and a small restaurant before sitting vacant for years.

In 1975, Bolivar County boasted 13 satellite clinics in addition to the main county health facility in Cleveland.

“We try, especially in the Cleveland office, to offer general health services every day of the week,” county health officer Dr. Dominic Tumminello, a Gunnison native, told the Clarion-Ledger that year. “When a person walks into our health clinic, we want to serve that person.”

The county health department building in Rosedale, a 10-minute drive away, closed in February 2016, along with eight other such facilities around the state. Today, there is only one county health department site in Bolivar, in Cleveland, and it is open only four days a week, with limited walk-ins and family planning services requiring a call ahead of time.

Rosedale’s pharmacy closed recently, too, when its owner retired.

The nearest hospital is 30 minutes away, in Cleveland.

The Delta’s population is declining and has declined dramatically since 1940– part of the reason why large hospitals built early in the 20th century are struggling.

In Bolivar County, 29% of adults lack health insurance. Thirty-six percent of county residents live in poverty, compared to 20% statewide.

The combination of poverty, lack of insurance, serious health needs and a small, spread-out population makes health care in the Delta a puzzle that is only becoming more complicated.

Yet Thomas has found a way to make it work, by winning federal and state grants that allow her to offer services on a sliding scale, so that patients without insurance can still afford to see her. Healthy Living Family Medical Center was designated a Rural Health Clinic by the health department, which means the federal government reimburses the clinic for primary care services. Thomas also offers family planning services through the Title X grant, participates in a tobacco cessation program through the Institute of Minority Health, and offers free COVID-19 testing and vaccines.

Her husband, Jervis McGee, sees how hard she works, taking calls from patients after hours and reading up on health issues in her free time.

“A lot of people forget that she’s a normal person, too,” he said.

For Thomas, it feels critical to offer as many services as possible to a community that needs them. But it’s also exhausting to participate in so many programs, each with its own paperwork requirements, and to try to develop expertise in so many areas.

She noticed that many of her patients struggle with anxiety and depression, though they don’t always use those labels for their symptoms. She tries to refer them to psychiatrists, but availability is limited. Efforts to bring a psychiatric nurse practitioner to the clinic one day a month or to offer telemedicine haven’t panned out. So now she’s planning to go back to school to earn certification as a psychiatric nurse practitioner.

Nora Gough-Davis, the nurse practitioner and clinic owner who helped train Thomas, said operating an independent family practice clinic is no easy task. After a decade in business, Gough-Davis is hoping to sell the clinics and focus on her work teaching nursing at Delta State. She wants to make sure any buyer keeps them open.

“I’m tired,” she said. “I want to make sure that access doesn’t leave.”

And all around independent family practice owners in the Delta, the walls are closing in, as hospitals flounder and county health departments cut hours and offices.

One of Thomas’s patients that Thursday was a woman named Jennie Usry. Usry has had headaches and memory loss ever since a fall on the job in June, and she needs to see a neurologist. A specialist in Clarksdale didn’t take her insurance. And when she tried to make an appointment at Greenwood Leflore, she told Thomas, it was impossible.

“The hospital closing down, so they not taking new patients,” Usry said. “But you a doctor, so you call, it might be different.”

“I don’t know,” Thomas said. “I don’t know if that will… but I will try.”

(A spokesperson for Greenwood Leflore said the hospital’s neurology clinic is still open and accepting new patients. During negotiations with the University of Mississippi Medical Center, the clinic did not make new appointments because it was unclear whether any deal with UMMC would allow neurology services to continue. Negotiations have ended with no deal and Greenwood Leflore hopes the legislature will approve funding that will allow it to stay open.)

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

1964: Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party was formed

April 26, 1964

Civil rights activists started the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party to challenge the state’s all-white regular delegation to the Democratic National Convention.

The regulars had already adopted this resolution: “We oppose, condemn and deplore the Civil Rights Act of 1964 … We believe in separation of the races in all phases of our society. It is our belief that the separation of the races is necessary for the peace and tranquility of all the people of Mississippi, and the continuing good relationship which has existed over the years.”

In reality, Black Mississippians had been victims of intimidation, harassment and violence for daring to try and vote as well as laws passed to disenfranchise them. As a result, by 1964, only 6% of Black Mississippians were permitted to vote. A year earlier, activists had run a mock election in which thousands of Black Mississippians showed they would vote if given an opportunity.

In August 1964, the Freedom Party decided to challenge the all-white delegation, saying they had been illegally elected in a segregated process and had no intention of supporting President Lyndon B. Johnson in the November election.

The prediction proved true, with white Mississippi Democrats overwhelmingly supporting Republican candidate Barry Goldwater, who opposed the Civil Rights Act. While the activists fell short of replacing the regulars, their courageous stand led to changes in both parties.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Mississippi River flooding Vicksburg, expected to crest on Monday

Warren County Emergency Management Director John Elfer said Friday floodwaters from the Mississippi River, which have reached homes in and around Vicksburg, will likely persist until early May. Elfer estimated there areabout 15 to 20 roads underwater in the area.

“We’re about half a foot (on the river gauge) from a major flood,” he said. “But we don’t think it’s going to be like in 2011, so we can kind of manage this.”

The National Weather projects the river to crest at 49.5 feet on Monday, making it the highest peak at the Vicksburg gauge since 2020. Elfer said some residents in north Vicksburg — including at the Ford Subdivision as well as near Chickasaw Road and Hutson Street — are having to take boats to get home, adding that those who live on the unprotected side of the levee are generally prepared for flooding.

“There are a few (inundated homes), but we’ve mitigated a lot of them,” he said. “Some of the structures have been torn down or raised. There are a few people that still live on the wet side of the levee, but they kind of know what to expect. So we’re not too concerned with that.”

The river first reached flood stage in the city — 43 feet — on April 14. State officials closed Highway 465, which connects the Eagle Lake community just north of Vicksburg to Highway 61, last Friday.

Elfer said the areas impacted are mostly residential and he didn’t believe any businesses have been affected, emphasizing that downtown Vicksburg is still safe for visitors. He said Warren County has worked with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Mississippi Emergency Management Agency to secure pumps and barriers.

“Everybody thus far has been very cooperative,” he said. “We continue to tell people stay out of the flood areas, don’t drive around barricades and don’t drive around road close signs. Not only is it illegal, it’s dangerous.”

NWS projects the river to stay at flood stage in Vicksburg until May 6. The river reached its record crest of 57.1 feet in 2011.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

With domestic violence law, victims ‘will be a number with a purpose,’ mother says

Joslin Napier. Carlos Collins. Bailey Mae Reed.

They are among Mississippi domestic violence homicide victims whose family members carried their photos as the governor signed a bill that will establish a board to study such deaths and how to prevent them.

Tara Gandy, who lost her daughter Napier in Waynesboro in 2022, said it’s a moment she plans to tell her 5-year-old grandson about when he is old enough. Napier’s presence, in spirit, at the bill signing can be another way for her grandson to feel proud of his mother.

“(The board) will allow for my daughter and those who have already lost their lives to domestic violence … to no longer be just a number,” Gandy said. “They will be a number with a purpose.”

Family members at the April 15 private bill signing included Ashla Hudson, whose son Collins, died last year in Jackson. Grandparents Mary and Charles Reed and brother Colby Kernell attended the event in honor of Bailey Mae Reed, who died in Oxford in 2023.

Joining them were staff and board members from the Mississippi Coalition Against Domestic Violence, the statewide group that supports shelters and advocated for the passage of Senate Bill 2886 to form a Domestic Violence Facility Review Board.

The law will go into effect July 1, and the coalition hopes to partner with elected officials who will make recommendations for members to serve on the board. The coalition wants to see appointees who have frontline experience with domestic violence survivors, said Luis Montgomery, public policy specialist for the coalition.

A spokesperson from Gov. Tate Reeves’ office did not respond to a request for comment Friday.

Establishment of the board would make Mississippi the 45th state to review domestic violence fatalities.

Montgomery has worked on passing a review board bill since December 2023. After an unsuccessful effort in 2024, the coalition worked to build support and educate people about the need for such a board.

In the recent legislative session, there were House and Senate versions of the bill that unanimously passed their respective chambers. Authors of the bills are from both political parties.

The review board is tasked with reviewing a variety of documents to learn about the lead up and circumstances in which people died in domestic violence-related fatalities, near fatalities and suicides – records that can include police records, court documents, medical records and more.

From each review, trends will emerge and that information can be used for the board to make recommendations to lawmakers about how to prevent domestic violence deaths.

“This is coming at a really great time because we can really get proactive,” Montgomery said.

Without a board and data collection, advocates say it is difficult to know how many people have died or been injured in domestic-violence related incidents.

A Mississippi Today analysis found at least 300 people, including victims, abusers and collateral victims, died from domestic violence between 2020 and 2024. That analysis came from reviewing local news stories, the Gun Violence Archive, the National Gun Violence Memorial, law enforcement reports and court documents.

Some recent cases the board could review are the deaths of Collins, Napier and Reed.

In court records, prosecutors wrote that Napier, 24, faced increased violence after ending a relationship with Chance Fabian Jones. She took action, including purchasing a firearm and filing for a protective order against Jones.

Jones’s trial is set for May 12 in Wayne County. His indictment for capital murder came on the first anniversary of her death, according to court records.

Collins, 25, worked as a nurse and was from Yazoo City. His ex-boyfriend Marcus Johnson has been indicted for capital murder and shooting into Collins’ apartment. Family members say Collins had filed several restraining orders against Johnson.

Johnson was denied bond and remains in jail. His trial is scheduled for July 28 in Hinds County.

He was a Jackson police officer for eight months in 2013. Johnson was separated from the department pending disciplinary action leading up to immediate termination, but he resigned before he was fired, Jackson police confirmed to local media.

Reed, 21, was born and raised in Michigan and moved to Water Valley to live with her grandparents and help care for her cousin, according to her obituary.

Kylan Jacques Phillips was charged with first degree murder for beating Reed, according to court records. In February, the court ordered him to undergo a mental evaluation to determine if he is competent to stand trial, according to court documents.

At the bill signing, Gandy said it was bittersweet and an honor to meet the families of other domestic violence homicide victims.

“We were there knowing we are not alone, we can travel this road together and hopefully find ways to prevent and bring more awareness about domestic violence,” she said.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days agoJim talks with Rep. Robert Andrade about his investigation into the Hope Florida Foundation

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days agoPrayer Vigil Held for Ronald Dumas Jr., Family Continues to Pray for His Return | April 21, 2025 | N

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed5 days agoTrump touts manufacturing while undercutting state efforts to help factories

-

Mississippi Today6 days ago

Mississippi Today6 days ago‘Trainwreck on the horizon’: The costly pains of Mississippi’s small water and sewer systems

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Texas News Feed6 days agoMeteorologist Chita Craft is tracking a Severe Thunderstorm Warning that's in effect now

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days agoAs country grows more polarized, America needs unity, the ‘Oklahoma Standard,’ Bill Clinton says

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed21 hours ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed21 hours agoMissouri lawmakers on the cusp of legalizing housing discrimination

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed5 days agoFederal report due on Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina’s path to recognition as a tribal nation