Kaiser Health News

An Arm and a Leg: When Hospitals Sue Patients (Part 1)

Dan Weissmann

Thu, 14 Dec 2023 10:00:00 +0000

Some hospitals sue patients over unpaid medical bills in bulk, sometimes by the hundreds of thousands. The defendants are often already facing financial hardship or even bankruptcy.

Judgments against patients in these suits can derail someone’s life but, according to experts, they don’t bring hospitals much money.

So why do hospitals do it?

Host Dan Weissmann investigates this practice with The Baltimore Banner and Scripps News and speaks to patients who’ve found themselves on the receiving end of such lawsuits.

Weissmann also speaks with Nick McLaughlin, an entrepreneur who’s making the business case for hospitals to stop trying to collect money from people who simply don’t have it.

Dan Weissmann

Host and producer of “An Arm and a Leg.” Previously, Dan was a staff reporter for Marketplace and Chicago’s WBEZ. His work also appears on All Things Considered, Marketplace, the BBC, 99 Percent Invisible, and Reveal, from the Center for Investigative Reporting.

Credits

Emily Pisacreta

Producer

Adam Raymonda

Audio wizard

Ellen Weiss

Editor

Bella Czajkowski

Producer

Click to open the Transcript

Transcript: When Hospitals Sue Patients (Part 1)

Note: “An Arm and a Leg” uses speech-recognition software to generate transcripts, which may contain errors. Please use the transcript as a tool but check the corresponding audio before quoting the podcast.

[birds singing]

Dan: Hey there. Starting this episode with a field trip.

[dogs barking]

Dan (from field tape): I hear dogs. I’m in the right place.

Dan: Nick McLaughlin lives outside Kalamazoo, Michigan. The email with his address said: Long gravel driveway, blue house. He’d said he’d be outside with his dogs, enjoying a cup of coffee. This is a big lot, with a pond on one side, a lake on the other, and huge trees all around.

Nick: So yeah, when I said I was sitting out enjoying a cup of coffee, this is a pretty good spot to do it. Pretty cool bird action. We had some neat, red headed woodpeckers going this morning.

Dan: He’s lived in the area since he was in high school. His parents still live nearby. So do his in laws. He’s married to his high school sweetheart — they got married while they were still in college. That’s also when Nick started working in medical collections.

Nick: I just saw a part time job listing in the college job website for a patient financial counselor. Didn’t know what that meant. Uh, and next thing I knew I had a, uh, headset on and was talking to patients about two and three year old hospital bills that they had. And my parents about disowned me. My mom’s a nurse, uh, and my dad’s a PhD environmental scientist. And so, um, Their line was, what are you doing calling sick people asking for money?

Dan: He says they came around. After a couple of years, he quit the call center and ended up in sales for a company called AmeriCollect. As the name suggests, they’re a collection agency. Specifically, medical-bill collections. Hospitals and medical groups are their clients. Nick started as Americollect’s first sales rep in Michigan, then after a year or so, branched out.

Nick: It was Michigan, Indiana. Ohio. Pennsylvania, and then North Carolina and, then we’re just kinda all over.

Dan: You were really good at this.

Nick: I was good at this.

Dan: Nick spent a decade at AmeriCollect. The company’s slogan was, is — and I swear this is true: “ridiculously nice.” It’s on their website — and Nick says it was part of their pitch to clients.

Nick: The pitch was, we’re going to be more effective in connecting with your people, maintaining your reputation, with them and your community, and, oh, by the way, we’re also effective at recovering the dollars that are owed to you, uh, by being ridiculously nice, was the line.

Dan: I’ve come to Nick for insights on one of the most ridiculously nasty parts of American health care: Because some hospitals and medical providers don’t just send bill collectors — nice or otherwise– after patients. Some hospitals sue their patients over unpaid bills — filing lawsuits by the hundreds, or even thousands, every year. And here’s a twist: These lawsuits don’t bring hospitals much money. So why do they do it? I’ve been interested in this question for years. And this year, I’ve had a lot of help chasing it, working with amazing journalists from two incredible news outlets. We had some ideas when we started — hypotheses, that we tested together. And those hypotheses… they were wrong. But we discovered something along the way that, well, no one else seems to have discovered yet. And for once, it’s actually not-bad news. Surprisingly hopeful. Of course we also learned things that made me super-mad… and the whole inquiry absolutely made clear some ways we can all look out for ourselves and each other. It’s a bunch. So we’re bringing it to you in a two-parter. Strap in.

With Scripps News and the Baltimore Banner, this is “An Arm and a Leg” — a show about why health care costs so freaking much, and what we can maybe do about it. I’m Dan Weissmann. I’m a reporter, and I like a challenge. So our job on this show is to take one of the most enraging, terrifying, depressing parts of American life, and bring you something entertaining, empowering, and useful. Before we get into big trends, numbers, all that– let’s start with just one family’s story.

Casey and Ron Gasior live in South Milwaukee. Our summer intern, Bella Czakowski, met them there in August.

Bella Czajkowski: Hi, Bella, nice to meet you. My husband, Ron.

Dan: Casey and Ron met in a bar almost 20 years ago. He was working there, and

then so was she. They were close– as friends.

Ron: A lot of people thought that we were together because we were so close.

Casey: But we never had anything to do with each other and that’s a sore subject. On his part. Because …

Bella: Because you were interested back then?

Ron: Yes. Yeah. Who knows, I mean, if we would have been together back then, it might not have lasted. She was young, I was older, but I still …I didn’t have my stuff together, you know. Whatever.

Dan: They married other people, drifted apart, and reconnected as friends years later –by which time both marriages were in trouble. Casey and Ron both got divorces, then got together, then bought this house eight months later. They got married in 2017. And then came the wave — waves– of medical issues.

Casey: His back, his knee, my heart.

Dan: Atrial fibrillation. That’s three procedures between them. And time off work to recover, less income. Another two procedures for Casey– carpal tunnel– more time away from work.

Casey: And at that time, too, I was also diagnosed with diabetes. So there was, there was a lot.

Dan: And there were lots of bills. They had insurance, but there’s always “Your portion.” It adds up. Plus Casey’s meds for diabetes and a-fib.

Casey: we would dig little bit out of our hole, and then we’d go right back down. And it to the where we we can’t even pay these

Dan: And then they started falling behind on house payments too.

Casey: There was a few nights in the garage, trying to figure out what our next step was.

Dan: In the garage, where Ron’s teenage daughter couldn’t hear.

Casey: We tried to do all of this without our daughter knowing, you know, cause

you don’t want to stress a kid out.

Dan: They decided the best of their bad options was Chapter 13 bankruptcy: Wrapping all their debts into a giant five-year payment plan. It would let them keep the house and their cars, if they were able to make the payments. It was really tough. The pandemic didn’t help. But in the spring of 2023, they were a couple months away from getting discharged, when they got a letter from a law firm– looking to collect money on a medical bill. It said…

Casey: That I needed to call them to make payment arrangements by a certain date Ron: Well, not to make arrangements. They wanted to payments. To make payments.

Casey: By a certain date. Otherwise, we’d be going to court.

Dan: The bill was three thousand dollars– for a medical procedure that happened before the bankruptcy. But the bill had come after. They say they called the lawyer, explained: Until we’re discharged from bankruptcy — which we will be soon — we’re actually not allowed to pay you. According to Casey and Ron, the lawyer was rude and said, essentially: See you in court. When they did, Casey says, the judge told the lawyer on the other side: These folks aren’t allowed to pay you anything until their bankruptcy is done. And told the Gasiors: When you’re discharged, do make arrangements to pay. So that’s one story– a lawsuit against folks who literally weren’t allowed to pay.

And every story is gonna be different, but the big picture: Lawsuits filed against people who — even without a court order — just couldn’t pay — that’s not a one-off. Lots of folks — reporters, researchers, advocates — have been documenting this phenomenon — hospitals suing patients by the hundreds or even thousands– for a long time. For instance, in Maryland, a study from 2020 found a hundred and forty thousand lawsuits that hospitals had filed against patients over a ten-year period. In New York, a series of reports looked at more than 50,000 lawsuits over just five years.

Elisabeth Benjamin co-wrote those New York reports. She’s the vice president for health initiatives at the Community Service Society of New York. And one of the findings that shocked her was: how small the amounts were that folks were being sued for– like, compared to a hospital’s bottom line. Or even compared to an average hospital bill.

Elisabeth Benjamin: They’re suing people for pennies. right. The average lawsuit is maybe 1900 bucks. So they’re suing them for chump change, but that $1,900 is like life ruining for the patient.

Dan: Because the people getting sued tend to be people who are just getting by– if they’re even getting by. Elisabeth Benjamin found: People whose wages get garnished to pay medical debts tend to work for low-wage employers. And our colleagues at the Baltimore Banner found that in Maryland, people who get sued over medical bills tend to live in census tracts where poverty is high. Elisabeth Benjamin turned up another finding that surprised her: The hospitals filing the most lawsuits were not always the kinds of places that were hard-up for money. And lots of hospitals that were hard up for money weren’t filing any lawsuits.

Elisabeth Benjamin: In other words, there’s many hospitals that are either making it or not making it, but are not suing people. At least in New York, most hospitals are good guys. I mean, they wouldn’t dream of suing people. And then there’s like this cruddy, top 20, top 15 that are responsible for huge amounts of the lawsuits. And it doesn’t seem like the amounts they’re suing for really has any bearing on any hospitals bottom line. So then it begs the question of, well, what are they doing this for in the first place?

Dan: That’s basically the question I started with. What are they doing this for in the first place? And I just want to underline one of Elisabeth Benjamin’s findings: not all hospitals do this– file lawsuits in bulk. Most hospitals don’t. Other studies have found the same thing. So, it’s not a necessity. It’s a choice. And for the majority of hospitals, it’s a choice that seems to run counter to a pretty important fact: They’re organized as non-profit charities. They pay no taxes, and they give donors big tax write-offs. And they’re legally obligated to provide charity care: To have policies saying how they’ll write off bills for folks who can’t pay.

I mean, even for-profit hospitals tend to have policies like that, without a legal obligation. So, suing people in bulk, … it’s an interesting choice. I wanted to talk with people who were part of the conversations where hospitals give the order: This is how we’re going to collect. And I got to talk with a couple of those people. One of them was Nick McLaughlin. Because Nick says, when a hospital sues patients– especially if they’re filing lawsuits in bulk, by the hundreds or thousands– a lot of the time, they’re not sending a staff attorney, or even picking a lawyer directly. The collection agency handles all that. But as Nick tells me: the strategy, the question of whether or not to sue, how hard to chase people– that all comes from the client, someone like the hospital’s revenue director.

Nick: We had clients at AmeriCollect where, they’d say, collect on it for six months and afterwards cancel it back.

Dan: Cancel it back. Meaning, cancel the assignment. Just don’t even bother trying to collect after six months. We’ll write it off.

Nick: And we’d say, you sure? Six months isn’t very long. And they’d say, “That’s what we want.” it’s more standard to be, two years.

Dan: What’s the recovery like in those intervening 18 months? Like how much more you get?

Nick: Not a ton.

Dan: Because — and this was the part that stuck with me the most– by the time a bill gets sent to a collection agency, it’s unlikely to actually be collected. When Nick was pitching AmeriCollect’s services, the pitch wasn’t, “We collect more than anybody else.” Because: that wasn’t a relevant pitch.

Nick: You’re normally not really gonna move the needle much from one collection agency to another. Meaning one collection agency might collect 10 percent, the next collection agency might collect 12 percent.

Dan: That’s a difference of two percent– but two percent of WHAT? Two percent of what’s already a very narrow slice of hospitals’ income.

I talked with an analyst for a consulting company called Kodiak– they run the numbers on this kind of thing. He said hospitals get about 90 percent of their money from insurance. By the time they send us bills, hospitals have already got 90 percent of their money. And then: a lot of people are able to pay their bills before getting sent to collections. Nick says maybe five or six percent of hospital bills– in dollars– get sent to collections at all. And Nick says, when you’re looking for someone to chase folks for that five or six percent, the difference between one agency and another is… not much.

Nick: One agency is collecting 10 percent of 5 percent and one agency is collecting 12 percent of 5%. We’re talking about a difference of, fractions of a fraction of a percent.

Dan: And even if ALL of the difference — the fractions of a fraction of a percent — is because you went hard after people, took them to court… it really looks like peanuts.

This lines up with what journalists and advocates have documented in their reports: They compare the total, aggregate amounts hospitals are suing for, and compare it to the institution’s annual surplus. Or pay for top executives. The amounts their suing for– total– always look tiny in comparison. So the decision to do something like sue people in bulk, it doesn’t seem to Nick like it’s based on numbers. In fact, here’s where the mystery gets deeper. Because: You may have noticed, Nick’s been talking about Americollect in the past tense. He doesn’t work there anymore. These days he runs his own business, pitching his old clients — and any other hospital system he can get to listen — on a completely different approach: No matter how ridiculously nice your collections agents may be, he tells them, you should be sending them a lot less business. You’d be better off forgiving those debts, through charity care, before ever sending the first bill. He’s pitching tech to help hospitals do that. And he’s not telling hospitals, you should do this to be nice. He’s telling them: this is better for your bottom line. How he got there, and the pitch he makes now– that’s next.

This episode of An Arm and a Leg is produced in partnership with KFF Health News– that’s a nonprofit newsroom covering health care in America. They are amazing journalists, and I learn from them all. The. Time. We’ll have a little more information about KFF Health News at the end of this episode.

This part of Nick’s story starts at a family holiday gathering in 2019. And a conversation with his wife’s grandfather, who was 86 at the time.

Nick: He and grandma were on social security and not a whole lot of extra resources. Pretty much your, standard salt of the earth, awesome people that serve everybody else and don’t have a ton. But are just fine with that.

Dan: But now grandpa had a 750 dollar hospital bill. Not so fine.

Nick: He said, Hey Nick, I know you know a lot about hospital bills. That’s a lot of money for an old guy like me. Do you know if there are any options ? And I said, Well, sure, Grandpa.Have you ever, looked into financial assistance? And he looked at me and said, What’s that?

Dan: Financial assistance — also known as charity care — is when a hospital agrees to reduce your bill, or just write it off, because you don’t make enough money to pay it.

And Nick knew all about charity care because since he’d started working at Americollect, having a charity care policy had become a legal obligation for nonprofit hospitals — which is to say, the majority of American hospitals — thanks to a provision in the Affordable Care Act.

Nick’s company, AmeriCollect, had kept on top of that new law, and he says they helped hospitals make sure they were complying with it.

Nick: We put together policy templates and sample financial assistance policies and application forms

Dan: He says it was, in its way, a long-game sales strategy. If you develop a reputation among hospitals as someone who’s trustworthy and helpful and smart, then next time they need a new bill collector, they’ll keep you in mind. Anyway, when Nick’s grandpa said, “What’s financial assistance?” Nick was ready to go.

Nick: I said, let’s see if you qualify um, so I pulled up, the hospital’s website and pulled up their financial assistance policy, um, which was 16 pages long. And I thought to myself, how in the world would grandpa get an answer to the question, do I qualify for financial assistance?

Dan: Nick has looked at a lot of super-long financial-assistance forms since then, and he can rattle off the kinds of questions they ask:

Nick: What kind of cars do you drive? Your make and model. How much do you think that it’s worth? And how much do you owe on it? What is the value of your primary residence? How much are you spending each month on house payment, car payment, groceries, cell phone bill, a breakdown of a monthly budget?

Dan: In other words, a LOT. Nick says some of the detailed questions were put there in anticipation of proposed federal laws and regulations that never got adopted. So, Nick was super well versed in all this stuff. He’d helped hospitals design their charity care policies.

Nick: But I hadn’t spent a whole lot of time thinking about what it would be like from the patient’s perspective to try to navigate a hospital’s financial assistance program.

Dan: He was like, before jumping into all this, Grandpa, let’s just figure out if it’s worth it. Are you likely to qualify? And Nick knew how to get an answer: Because he knew, the way hospital charity-care policies work is: They compare your income to a multiple of the federal poverty level. At this hospital it was 250 percent. Nick learned what grandma and grandpa got from social security, compared it to that federal poverty number.

Nick: And so I was like, all right, well, hey grandpa, it looks like you’re going to qualify for financial assistance, let’s print out an application and start filling it out. It was bare because it was a beast of an application. But eventually he was approved for Medicaid and never received another hospital bill for the rest of his life.

Dan: And the 750 bucks?

Nick: Disappeared.

Dan: It got Nick thinking about a presentation he’d seen a couple of years before. This was when a lot of hospitals were first rolling out their charity-care policies to comply with the new law. One of the national Catholic hospital chains was giving a talk about their policy.

Nick: We offer 75 percent discounts up to 400 percent of the federal poverty level. And I just kind of sat back in my chair and thought, 400 percent of the federal

poverty level.

Dan: That sounded like it might cover a lot of people. Like, how many people in this country make less than that? Maybe a lot. He looked it up later, and I did too:

4 times the federal poverty level for a single person is about 58 thousand a year. And almost 60 percent of Americans make less than that.

Nick: So the next logical step is, Okay, well, uh, People that hospitals send to collections, would you imagine that they have higher incomes or lower incomes than your average American? I think it’s fair to say that we can guess that they’re lower on the income scale than the average American.

Dan: So it would seem like most people who get sent to collections… would’ve qualified for financial assistance. And since, according to industry consultants, most BILLS that get sent to collections never get collected it also seems like: A lot of people who are getting chased by collections agents, maybe getting sued, would have qualified for charity care. Which, duh, maybe. I mean, a lot of reporters and advocates have written a lot of reports showing exactly that. To a lot of people, it looks like an outrage. But with Nick’s knowledge of hospital revenue departments, he saw it as something else: An opportunity. By spending all that effort on chasing folks who wouldn’t and couldn’t pay, hospitals were WASTING MONEY on that effort. And– again, because Nick really knows the nerdy details– he figured hospitals were also leaving other money on the table. Like from Medicaid, which would be paying for Grandpa’s hospital bills– not just for that first 750 dollar charge, but on every bill for the rest of his life. That’s money the hospital would’ve had a hard time getting from grandpa. And Nick thought: A guy could build a business helping hospitals save money over here and pick up money over there. So he quit his job at AmeriCollect to start that business. I asked him to do his pitch for me.

Nick: Uh, pitch. Are you looking for basically what we present to hospitals and stuff like that? Yeah.

Dan: He does this at conferences a few times a year. He pulled up PowerPoint, put it in Presenter View.

Nick: Love presenter view. Hey, let me just fire away. Yeah.

Dan: And we were off.

Nick: So, as the host mentioned, I spent my first 12 years in the industry in the hospital billing and collections world.

Dan: Nick skipped a few details– actually, looking over his shoulder I noticed a key one.

Dan (from field tape): this paragraph that you skipped, like, the cost of sending those bills, you’re saying, like, 2 dollars per.

Nick: Oh, yeah

Dan: Two bucks out of pocket. Even though it’s all automated, you’re spending a lot on the machines, the software, the paper– not to mention postage. And if someone’s headed to collections, you’re not just sending them one bill.

Nick: if you think about three statements and a final notice, and customer service cost for supporting all of that, it’s not insignificant.

Dan: Oh yeah: Customer service cost. That’s the call center. So that’s savings. Then there’s money you pick up. Nick proposes that hospitals basically just ask people their income up front, along with their insurance information. He’s offering them an easy web form to give patients. And he says when hospitals use that form, like ten percent of patients turn out to be eligible for Medicaid. He tells hospitals:

Nick: These are great opportunities to help them get on the Medicaid program, and help you get paid for the care that you provided.

Dan: And Nick says Medicaid isn’t the only opportunity to get paid. Lots of people with regular insurance also have deductibles and other “patient responsibilities” that can get into the thousands of dollars. Which makes a lot of people think twice about going in for care, if they can avoid it. And: Not only could a lot of those people meet the income requirements for charity care– remember, almost 60 percent could meet those requirements at some hospitals — hospitals can adopt charity-care policies that cover people who do have insurance. Which, Nick argues can be a money-making opportunity.

Nick: Um, a question I like to pose is: If a low income patient is on the fence about getting a procedure at your hospital, for example, a knee replacement, that will get you paid 15,000 by their insurance…

Dan: … then wouldn’t it be smart to offer them charity care so they don’t worry about their deductible? You’d be unlocking that 15 thousand dollars from their insurance company. Nick’s pitch sounded pretty solid to me. He’s got some clients, and a backer — a bigger company that’s investing in his work. He says people chat him up after he gives these talks… but he does hear some — not pushback, exactly. More like…

Nick: Eh, we’ll do what we need to do to be compliant, but we’ve got other things to deal with that, we’re not really going to worry about this too much.

Dan: In other words, it’s not a priority. Maybe not where the big money is. But then, lawsuits — especially lawsuits against people who can’t pay– aren’t where the big money is either. Why do these folks allow themselves to be literally party to them?

Nick: It’s really, I would say philosophically-based.

Dan: Philosophically-based. Up to the philosophy of the collection agency and the hospital revenue director. In part two of this story, we’ll hear from someone in the collections world who’s ready to argue, philosophically, that it’s OK to sue people for medical bills they just can’t pay.

Scott Purcell: If you just sued somebody who can’t pay, they’re not out any money. So you made a bad business decision. But truly Dan, what is the harm they’re experiencing?

Dan: And we’ll hear about the case of the disappearing lawsuits’

Ryan Little: So on September 18th, I said, Maryland hospitals are dot, dot, dot…

Basically not suing anyone for medical debt anymore.

Dan: Yep!

Meanwhile, this is a GREAT time to make a donation to keep this show going. Projects like this take a TON of time and money. And right now, every dollar you give is being MATCHED by other “Arm and a Leg” listeners.

The NewsMatch program from the Institute for Nonprofit News has matched as much as they can for this year, and a few super-generous listeners have put up MORE matching funds. Go take them up on it!

There’s a link in the show notes, wherever you’re listening, or head to arm-and-a-leg-show, dot com, slash, support. (https://armandalegshow.com/support/)

Thank you so much! Your help makes a huge difference. We’ll be back in two weeks with part two.

Till then, take care of yourself.

This episode of An Arm and a Leg was produced by me, Dan Weissmann, with help from Bella Czakowski and Emily Pisacreta in partnership with the Scripps News, the Baltimore Banner, and the McGraw Center for Business Journalism at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at the City University of New York.

Our work on this story is supported by the Fund for Investigative Journalism, and edited by Ellen Weiss.

Daisy Rosario is An Arm and a Leg’s consulting managing producer.

Gabrielle Healy is our managing editor for audience — she edits the First Aid Kit newsletter.

Sarah Ballema is our Operations Manager.

Bea Bosco is our Consulting Director of Operations.

An Arm and a Leg is produced in partnership with KFF Health News.

That’s a national newsroom producing in-depth journalism about health care in America, and a core program at KFF — an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism.

You can learn more about KFF Health News at arm and a leg show dot com, slash KFF. (https://armandalegshow.com/about-x/partners-and-supporters/kaiserhealthnews/)

Zach Dyer is senior audio producer at KFF Health News. He is editorial liaison to this show.

Thanks to the INSTITUTE FOR NONPROFIT NEWS for serving as our fiscal sponsor, allowing us to accept tax-exempt donations. You can learn more about INN at I-N-N dot org. (https://inn.org/)

And, finally, thanks to everybody who supports this show financially.

If you haven’t yet, we’d love for you to pitch in to join us. Again, the place for that is arm and a leg show dot com, slash support.(https://armandalegshow.com/support/)

“An Arm and a Leg” is a co-production of KFF Health News and Public Road Productions.

This episode was produced in partnership with Scripps News, The Baltimore Banner, and the McGraw Center for Business Journalism at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at the City University of New York.

Work by “An Arm and a Leg” on this article is supported by the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

To keep in touch with “An Arm and a Leg,” subscribe to the newsletter. You can also follow the show on Facebook and X, formerly known as Twitter. And if you’ve got stories to tell about the health care system, the producers would love to hear from you.

To hear all KFF Health News podcasts, click here.

And subscribe to “An Arm and a Leg” on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

——————————

By: Dan Weissmann

Title: An Arm and a Leg: When Hospitals Sue Patients (Part 1)

Sourced From: kffhealthnews.org/news/podcast/when-hospitals-sue-patients-part-1/

Published Date: Thu, 14 Dec 2023 10:00:00 +0000

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/millions-in-opioid-settlement-funds-sit-untouched-as-overdose-deaths-rise/

Kaiser Health News

US Judge Names Receiver To Take Over California Prisons’ Mental Health Program

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — A judge has initiated a federal court takeover of California’s troubled prison mental health system by naming the former head of the Federal Bureau of Prisons to serve as receiver, giving her four months to craft a plan to provide adequate care for tens of thousands of prisoners with serious mental illness.

Senior U.S. District Judge Kimberly Mueller issued her order March 19, identifying Colette Peters as the nominated receiver. Peters, who was Oregon’s first female corrections director and known as a reformer, ran the scandal-plagued federal prison system for 30 months until President Donald Trump took office in January. During her tenure, she closed a women’s prison in Dublin, east of Oakland, that had become known as the “rape club.”

Michael Bien, who represents prisoners with mental illness in the long-running prison lawsuit, said Peters is a good choice. Bien said Peters’ time in Oregon and Washington, D.C., showed that she “kind of buys into the fact that there are things we can do better in the American system.”

“We took strong objection to many things that happened under her tenure at the BOP, but I do think that this is a different job and she’s capable of doing it,” said Bien, whose firm also represents women who were housed at the shuttered federal women’s prison.

California corrections officials called Peters “highly qualified” in a statement, while Gov. Gavin Newsom’s office did not immediately comment. Mueller gave the parties until March 28 to show cause why Peters should not be appointed.

Peters is not talking to the media at this time, Bien said. The judge said Peters is to be paid $400,000 a year, prorated for the four-month period.

About 34,000 people incarcerated in California prisons have been diagnosed with serious mental illnesses, representing more than a third of California’s prison population, who face harm because of the state’s noncompliance, Mueller said.

Appointing a receiver is a rare step taken when federal judges feel they have exhausted other options. A receiver took control of Alabama’s correctional system in 1976, and they have otherwise been used to govern prisons and jails only about a dozen times, mostly to combat poor conditions caused by overcrowding. Attorneys representing inmates in Arizona have asked a judge to take over prison health care there.

Mueller’s appointment of a receiver comes nearly 20 years after a different federal judge seized control of California’s prison medical system and installed a receiver, currently J. Clark Kelso, with broad powers to hire, fire, and spend the state’s money.

California officials initially said in August that they would not oppose a receivership for the mental health program provided that the receiver was also Kelso, saying then that federal control “has successfully transformed medical care” in California prisons. But Kelso withdrew from consideration in September, as did two subsequent candidates. Kelso said he could not act “zealously and with fidelity as receiver in both cases.”

Both cases have been running for so long that they are now overseen by a second generation of judges. The original federal judges, in a legal battle that reached the U.S. Supreme Court, more than a decade ago forced California to significantly reduce prison crowding in a bid to improve medical and mental health care for incarcerated people.

State officials in court filings defended their improvements over the decades. Prisoners’ attorneys countered that treatment remains poor, as evidenced in part by the system’s record-high suicide rate, topping 31 suicides per 100,000 prisoners, nearly double that in federal prisons.

“More than a quarter of the 30 class-members who died by suicide in 2023 received inadequate care because of understaffing,” prisoners’ attorneys wrote in January, citing the prison system’s own analysis. One prisoner did not receive mental health appointments for seven months “before he hanged himself with a bedsheet.”

They argued that the November passage of a ballot measure increasing criminal penalties for some drug and theft crimes is likely to increase the prison population and worsen staffing shortages.

California officials argued in January that Mueller isn’t legally justified in appointing a receiver because “progress has been slow at times but it has not stalled.”

Mueller has countered that she had no choice but to appoint an outside professional to run the prisons’ mental health program, given officials’ intransigence even after she held top officials in contempt of court and levied fines topping $110 million in June. Those extreme actions, she said, only triggered more delays.

The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals on March 19 upheld Mueller’s contempt ruling but said she didn’t sufficiently justify calculating the fines by doubling the state’s monthly salary savings from understaffing prisons. It upheld the fines to the extent that they reflect the state’s actual salary savings but sent the case back to Mueller to justify any higher penalty.

Mueller had been set to begin additional civil contempt proceedings against state officials for their failure to meet two other court requirements: adequately staffing the prison system’s psychiatric inpatient program and improving suicide prevention measures. Those could bring additional fines topping tens of millions of dollars.

But she said her initial contempt order has not had the intended effect of compelling compliance. Mueller wrote as far back as July that additional contempt rulings would also be likely to be ineffective as state officials continued to appeal and seek delays, leading “to even more unending litigation, litigation, litigation.”

She went on to foreshadow her latest order naming a receiver in a preliminary order: “There is one step the court has taken great pains to avoid. But at this point,” Mueller wrote, “the court concludes the only way to achieve full compliance in this action is for the court to appoint its own receiver.”

This article was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

If you or someone you know may be experiencing a mental health crisis, contact the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline by dialing or texting “988.”

The post US Judge Names Receiver To Take Over California Prisons’ Mental Health Program appeared first on kffhealthnews.org

Kaiser Health News

Amid Plummeting Diversity at Medical Schools, a Warning of DEI Crackdown’s ‘Chilling Effect’

The Trump administration’s crackdown on DEI programs could exacerbate an unexpectedly steep drop in diversity among medical school students, even in states like California, where public universities have been navigating bans on affirmative action for decades. Education and health experts warn that, ultimately, this could harm patient care.

Since taking office, President Donald Trump has issued a handful of executive orders aimed at terminating all diversity, equity, and inclusion, or DEI, initiatives in federally funded programs. And in his March 4 address to Congress, he described the Supreme Court’s 2023 decision banning the consideration of race in college and university admissions as “brave and very powerful.”

Last month, the Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights — which lost about 50% of its staff in mid-March — directed schools, including postsecondary institutions, to end race-based programs or risk losing federal funding. The “Dear Colleague” letter cited the Supreme Court’s decision.

Paulette Granberry Russell, president and CEO of the National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education, said that “every utterance of ‘diversity’ is now being viewed as a violation or considered unlawful or illegal.” Her organization filed a lawsuit challenging Trump’s anti-DEI executive orders.

While California and eight other states — Arizona, Florida, Idaho, Michigan, Nebraska, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, and Washington — had already implemented bans of varying degrees on race-based admissions policies well before the Supreme Court decision, schools bolstered diversity in their ranks with equity initiatives such as targeted scholarships, trainings, and recruitment programs.

But the court’s decision and the subsequent state-level backlash — 29 states have since introduced bills to curb diversity initiatives, according to data published by the Chronicle of Higher Education — have tamped down these efforts and led to the recent declines in diversity numbers, education experts said.

After the Supreme Court’s ruling, the numbers of Black and Hispanic medical school enrollees fell by double-digit percentages in the 2024-25 school year compared with the previous year, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges. Black enrollees declined 11.6%, while the number of new students of Hispanic origin fell 10.8%. The decline in enrollment of American Indian or Alaska Native students was even more dramatic, at 22.1%. New Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander enrollment declined 4.3%.

“We knew this would happen,” said Norma Poll-Hunter, AAMC’s senior director of workforce diversity. “But it was double digits — much larger than what we anticipated.”

The fear among educators is the numbers will decline even more under the new administration.

At the end of February, the Education Department launched an online portal encouraging people to “report illegal discriminatory practices at institutions of learning,” stating that students should have “learning free of divisive ideologies and indoctrination.” The agency later issued a “Frequently Asked Questions” document about its new policies, clarifying that it was acceptable to observe events like Black History Month but warning schools that they “must consider whether any school programming discourages members of all races from attending.”

“It definitely has a chilling effect,” Poll-Hunter said. “There is a lot of fear that could cause institutions to limit their efforts.”

Numerous requests for comment from medical schools about the impact of the anti-DEI actions went unreturned. University presidents are staying mum on the issue to protect their institutions, according to reporting from The New York Times.

Utibe Essien, a physician and UCLA assistant professor, said he has heard from some students who fear they won’t be considered for admission under the new policies. Essien, who co-authored a study on the effect of affirmative action bans on medical schools, also said students are worried medical schools will not be as supportive toward students of color as in the past.

“Both of these fears have the risk of limiting the options of schools folks apply to and potentially those who consider medicine as an option at all,” Essien said, adding that the “lawsuits around equity policies and just the climate of anti-diversity have brought institutions to this place where they feel uncomfortable.”

In early February, the Pacific Legal Foundation filed a lawsuit against the University of California-San Francisco’s Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland over an internship program designed to introduce “underrepresented minority high school students to health professions.”

Attorney Andrew Quinio filed the suit, which argues that its plaintiff, a white teenager, was not accepted to the program after disclosing in an interview that she identified as white.

“From a legal standpoint, the issue that comes about from all this is: How do you choose diversity without running afoul of the Constitution?” Quinio said. “For those who want diversity as a goal, it cannot be a goal that is achieved with discrimination.”

UC Health spokesperson Heather Harper declined to comment on the suit on behalf of the hospital system.

Another lawsuit filed in February accuses the University of California of favoring Black and Latino students over Asian American and white applicants in its undergraduate admissions. Specifically, the complaint states that UC officials pushed campuses to use a “holistic” approach to admissions and “move away from objective criteria towards more subjective assessments of the overall appeal of individual candidates.”

The scrutiny of that approach to admissions could threaten diversity at the UC-Davis School of Medicine, which for years has employed a “race-neutral, holistic admissions model” that reportedly tripled enrollment of Black, Latino, and Native American students.

“How do you define diversity? Does it now include the way we consider how someone’s lived experience may be influenced by how they grew up? The type of school, the income of their family? All of those are diversity,” said Granberry Russell, of the National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education. “What might they view as an unlawful proxy for diversity equity and inclusion? That’s what we’re confronted with.”

California Attorney General Rob Bonta, a Democrat, recently joined other state attorneys general to issue guidance urging that schools continue their DEI programs despite the federal messaging, saying that legal precedent allows for the activities. California is also among several states suing the administration over its deep cuts to the Education Department.

If the recent decline in diversity among newly enrolled students holds or gets worse, it could have long-term consequences for patient care, academic experts said, pointing toward the vast racial disparities in health outcomes in the U.S., particularly for Black people.

A higher proportion of Black primary care doctors is associated with longer life expectancy and lower mortality rates among Black people, according to a 2023 study published by the JAMA Network.

Physicians of color are also more likely to build their careers in medically underserved communities, studies have shown, which is increasingly important as the AAMC projects a shortage of up to 40,400 primary care doctors by 2036.

“The physician shortage persists, and it’s dire in rural communities,” Poll-Hunter said. “We know that diversity efforts are really about improving access for everyone. More diversity leads to greater access to care — everyone is benefiting from it.”

This article was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

The post Amid Plummeting Diversity at Medical Schools, a Warning of DEI Crackdown’s ‘Chilling Effect’ appeared first on kffhealthnews.org

Kaiser Health News

Tribal Health Leaders Say Medicaid Cuts Would Decimate Health Programs

As Congress mulls potentially massive cuts to federal Medicaid funding, health centers that serve Native American communities, such as the Oneida Community Health Center near Green Bay, Wisconsin, are bracing for catastrophe.

That’s because more than 40% of the about 15,000 patients the center serves are enrolled in Medicaid. Cuts to the program would be detrimental to those patients and the facility, said Debra Danforth, the director of the Oneida Comprehensive Health Division and a citizen of the Oneida Nation.

“It would be a tremendous hit,” she said.

The facility provides a range of services to most of the Oneida Nation’s 17,000 people, including ambulatory care, internal medicine, family practice, and obstetrics. The tribe is one of two in Wisconsin that have an “open-door policy,” Danforth said, which means that the facility is open to members of any federally recognized tribe.

But Danforth and many other tribal health officials say Medicaid cuts would cause service reductions at health facilities that serve Native Americans.

Indian Country has a unique relationship to Medicaid, because the program helps tribes cover chronic funding shortfalls from the Indian Health Service, the federal agency responsible for providing health care to Native Americans.

Medicaid has accounted for about two-thirds of third-party revenue for tribal health providers, creating financial stability and helping facilities pay operational costs. More than a million Native Americans enrolled in Medicaid or the closely related Children’s Health Insurance Program also rely on the insurance to pay for care outside of tribal health facilities without going into significant medical debt. Tribal leaders are calling on Congress to exempt tribes from cuts and are preparing to fight to preserve their access.

“Medicaid is one of the ways in which the federal government meets its trust and treaty obligations to provide health care to us,” said Liz Malerba, director of policy and legislative affairs for the United South and Eastern Tribes Sovereignty Protection Fund, a nonprofit policy advocacy organization for 33 tribes spanning from Texas to Maine. Malerba is a citizen of the Mohegan Tribe.

“So we view any disruption or cut to Medicaid as an abrogation of that responsibility,” she said.

Tribes face an arduous task in providing care to a population that experiences severe health disparities, a high incidence of chronic illness, and, at least in western states, a life expectancy of 64 years — the lowest of any demographic group in the U.S. Yet, in recent years, some tribes have expanded access to care for their communities by adding health services and providers, enabled in part by Medicaid reimbursements.

During the last two fiscal years, five urban Indian organizations in Montana saw funding growth of nearly $3 million, said Lisa James, director of development for the Montana Consortium for Urban Indian Health, during a webinar in February organized by the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families and the National Council of Urban Indian Health.

The increased revenue was “instrumental,” James said, allowing clinics in the state to add services that previously had not been available unless referred out for, including behavioral health services. Clinics were also able to expand operating hours and staffing.

Montana’s five urban Indian clinics, in Missoula, Helena, Butte, Great Falls, and Billings, serve 30,000 people, including some who are not Native American or enrolled in a tribe. The clinics provide a wide range of services, including primary care, dental care, disease prevention, health education, and substance use prevention.

James said Medicaid cuts would require Montana’s urban Indian health organizations to cut services and limit their ability to address health disparities.

American Indian and Alaska Native people under age 65 are more likely to be uninsured than white people under 65, but 30% rely on Medicaid compared with 15% of their white counterparts, according to KFF data for 2017 to 2021. More than 40% of American Indian and Alaska Native children are enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP, which provides health insurance to kids whose families are not eligible for Medicaid. KFF is a health information nonprofit that includes KFF Health News.

A Georgetown Center for Children and Families report from January found the share of residents enrolled in Medicaid was higher in counties with a significant Native American presence. The proportion on Medicaid in small-town or rural counties that are mostly within tribal statistical areas, tribal subdivisions, reservations, and other Native-designated lands was 28.7%, compared with 22.7% in other small-town or rural counties. About 50% of children in those Native areas were enrolled in Medicaid.

The federal government has already exempted tribes from some of Trump’s executive orders. In late February, Department of Health and Human Services acting general counsel Sean Keveney clarified that tribal health programs would not be affected by an executive order that diversity, equity, and inclusion government programs be terminated, but that the Indian Health Service is expected to discontinue diversity and inclusion hiring efforts established under an Obama-era rule.

HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. also rescinded the layoffs of more than 900 IHS employees in February just hours after they’d received termination notices. During Kennedy’s Senate confirmation hearings, he said he would appoint a Native American as an assistant HHS secretary. The National Indian Health Board, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit that advocates for tribes, in December endorsed elevating the director of the Indian Health Service to assistant secretary of HHS.

Jessica Schubel, a senior health care official in Joe Biden’s White House, said exemptions won’t be enough.

“Just because Native Americans are exempt doesn’t mean that they won’t feel the impact of cuts that are made throughout the rest of the program,” she said.

State leaders are also calling for federal Medicaid spending to be spared because cuts to the program would shift costs onto their budgets. Without sustained federal funding, which can cover more than 70% of costs, state lawmakers face decisions such as whether to change eligibility requirements to slim Medicaid rolls, which could cause some Native Americans to lose their health coverage.

Tribal leaders noted that state governments do not have the same responsibility to them as the federal government, yet they face large variations in how they interact with Medicaid depending on their state programs.

President Donald Trump has made seemingly conflicting statements about Medicaid cuts, saying in an interview on Fox News in February that Medicaid and Medicare wouldn’t be touched. In a social media post the same week, Trump expressed strong support for a House budget resolution that would likely require Medicaid cuts.

The budget proposal, which the House approved in late February, requires lawmakers to cut spending to offset tax breaks. The House Committee on Energy and Commerce, which oversees spending on Medicaid and Medicare, is instructed to slash $880 billion over the next decade. The possibility of cuts to the program that, together with CHIP, provides insurance to 79 million people has drawn opposition from national and state organizations.

The federal government reimburses IHS and tribal health facilities 100% of billed costs for American Indian and Alaska Native patients, shielding state budgets from the costs.

Because Medicaid is already a stopgap fix for Native American health programs, tribal leaders said it won’t be a matter of replacing the money but operating with less.

“When you’re talking about somewhere between 30% to 60% of a facility’s budget is made up by Medicaid dollars, that’s a very difficult hole to try and backfill,” said Winn Davis, congressional relations director for the National Indian Health Board.

Congress isn’t required to consult tribes during the budget process, Davis added. Only after changes are made by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and state agencies are tribes able to engage with them on implementation.

The amount the federal government spends funding the Native American health system is a much smaller portion of its budget than Medicaid. The IHS projected billing Medicaid about $1.3 billion this fiscal year, which represents less than half of 1% of overall federal spending on Medicaid.

“We are saving more lives,” Malerba said of the additional services Medicaid covers in tribal health care. “It brings us closer to a level of 21st century care that we should all have access to but don’t always.”

This article was published with the support of the Journalism & Women Symposium (JAWS) Health Journalism Fellowship, assisted by grants from The Commonwealth Fund.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

The post Tribal Health Leaders Say Medicaid Cuts Would Decimate Health Programs appeared first on kffhealthnews.org

-

Mississippi Today7 days ago

Mississippi Today7 days agoLawmakers used to fail passing a budget over policy disagreement. This year, they failed over childish bickering.

-

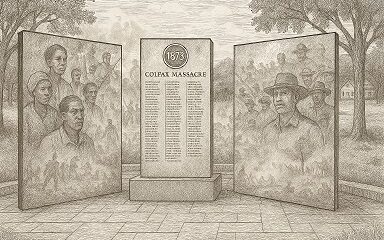

Mississippi Today7 days ago

Mississippi Today7 days agoOn this day in 1873, La. courthouse scene of racial carnage

-

Local News7 days ago

Local News7 days agoSouthern Miss Professor Inducted into U.S. Hydrographer Hall of Fame

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days agoFoley man wins Race to the Finish as Kyle Larson gets first win of 2025 Xfinity Series at Bristol

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days agoFederal appeals court upholds ruling against Alabama panhandling laws

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Texas News Feed7 days ago1 dead after 7 people shot during large gathering at Crosby gas station, HCSO says

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days agoJacksonville University only school with 2 finalist teams in NASA’s 2025 Human Lander Challenge

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days agoInsects as food? ‘We are largely ignoring the largest group of organisms on earth’