Kaiser Health News

An Arm and a Leg: The Medicare Episode

Dan Weissmann

Mon, 11 Mar 2024 09:00:00 +0000

Medicare may sound like an escape from the expensive world of U.S. health insurance, but it’s more complicated, and expensive, than many realize. And decisions seniors make when they sign up for the federal health insurance program can have huge consequences down the road.

Host Dan Weissmann speaks with Sarah Jane Tribble, KFF Health News’ chief rural health correspondent, about one of the biggest choices seniors must make: whether to enroll in traditional Medicare or the privatized version, Medicare Advantage.

Then, Weissmann shares practical tips about how soon-to-be seniors can avoid penalties and pick the plan that’s right for them.

Dan Weissmann

Host and producer of “An Arm and a Leg.” Previously, Dan was a staff reporter for Marketplace and Chicago’s WBEZ. His work also appears on All Things Considered, Marketplace, the BBC, 99 Percent Invisible, and Reveal, from the Center for Investigative Reporting.

Credits

Emily Pisacreta

Producer

Adam Raymonda

Audio wizard

Ellen Weiss

Editor

Click to open the Transcript

Transcript: The Medicare Episode

Note: “An Arm and a Leg” uses speech-recognition software to generate transcripts, which may contain errors. Please use the transcript as a tool but check the corresponding audio before quoting the podcast.

Dan: Hey there–

So, one thing we have never talked about on this show? Medicare. You know, that free-health-care thing you may expect to get when you turn 65.

It’s been on a list of things where I’ve been like, “that is TOO big, and TOO complicated. I can’t get my arms around that just now.”

Especially because: There’s this thing called Medicare Advantage — a kind of privatized version, run by insurance companies? Seems controversial, and REALLY complicated.

I’ve been like, Maybe someday.

And that someday? That’s today. Or at least, we start today. Mainly because a colleague of mine just did a BUNCH of work that we get to piggyback off of.

Sarah Jane Tribble: my name is Sarah Jane Tribble and I’m Chief Rural Health Correspondent with KFF Health News.

Dan: And as Sarah Jane reported on Medicare, she was surprised by how much she didn’t know. And how much other folks didn’t know either.

Sarah Jane Tribble: At Thanksgiving, when I was working on some of these stories, I have friends who are nearing retirement. They’re not really close , but they’re close enough to care and they’re avid NPR listeners. And they were like, wait, so what’s the difference between Medicare Advantage and Medicare? And I was like, they should know.

Dan: Who’s going to tell them?

Sarah Jane Tribble: Right?

Dan: That’s us, I guess.

Sarah Jane Tribble: This show will help tell them.

Dan-in-tape: I hope so. I hope so.

Dan: Because this traditional-Medicare vs Medicare Advantage — it is a high stakes decision, it happens when you first sign up.

And here’s the big thing that Sarah Jane learned: if you sign up for Medicare Advantage, at that point, when you first get on Medicare, you’re pretty much stuck with it. And some people end up with buyer’s remorse. Big time.

And actually, beyond that choice — between Medicare Advantage and what’s called “traditional Medicare” –, there’s literally a whole alphabet soup of other choices you’re gonna need to make. Each with a price tag, and maybe some big trade-offs.

And there’s been a lot of questionable information that comes at people. TV shows that older folks watch have been full of ads with People Who Were Real Famous in the 1970s.

J.J. Walker: Hi, I’m Jimmy JJ Walker.

Joe Namath: Hi, I’m Joe Namath.

William Shatner: William Shatner here with an important message. I’ve been on Medicare for longer than I’ll admit, and it sure has changed.

Dan: Some of these ads make claims that sound too good to be true

J.J. Walker: And get this, I’m entitled to an extra 100 a month. That’s 1, 200 a year added to my social security check. And I was like, dyn-o-mite!

Dan: Last year, the feds finalized new rules to try and rein in sketchy claims from some ads like these.

So understanding what’s going on, it’s a big deal. We’ll run down what I’ve learned so far, including some extremely expert guidance.

Our expert, by the way, set me straight on a bunch of things, including, sadly, this: Medicare isn’t actually the free-health-care thingy some of us hope for.

Sarah Murdoch: Unfortunately, I think a lot of people think, Oh, Medicare is going to be free , it unfortunately is not.

Dan: The question is how much it’s going to cost you– in dollars, and maybe in your choices managing your own health care. And surprise! It’s super complicated.

So by the time we’re done, you’re gonna understand the difference between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare — and how to start sorting through the alphabet soup.We’ll also leave you with some solid resources to figure out what your best choice might be when the time comes, either for you or somebody you care about.

Let’s do it.

This is “An Arm and a Leg,” a show about why health care costs so freaking much, and what we can maybe do about it. I’m Dan Weissmann. I’m a reporter. I like a challenge — so the job we’ve chosen here is to take one of the most enraging, terrifying, depressing parts of American life, and bring you something entertaining, empowering, and useful.

OK, when it comes to Medicare, the biggest choice folks have to make is between traditional Medicare — run directly by the government — and Medicare Advantage plans, which are run by private insurance companies. And again, that’s plans, because a bunch of different insurance companies offer different Medicare Advantage plans.

And last year, Sarah Jane Tribble started hearing from CEOs of rural hospitals.

They were telling her: Medicare Advantage plans are killing us. We’re spending a ton of time and money fighting with these insurance companies to get paid. And sometimes we don’t get paid.

Sarah Jane Tribble: And then I was also hearing about patients showing up at the hospital and these local hospitals saying, “oh, no, we actually don’t take your plan.” And so you’ve got these small town, you know, folks who have only one hospital and a long, you know, large radius. And they would show up and the hospital would be like, “Ah, you’re going to have to pay out of pocket because we don’t take this Medicare Advantage plan.” And the patient, of course, would be like, “but I’m on Medicare, you’re supposed to take care of me.”

Dan: Yeah. Isn’t that deal with Medicare? Everybody accepts it. You get on Medicare, you’re taken care of?

Sarah Jane Tribble: I began wondering, how much does signing up for a Medicare Advantage plan actually affect the care you get?

Dan: And the answer seems like: Maybe a lot.

A little Google searching turns up a lot of headlines about claims getting denied, and about hospitals dropping Medicare Advantage plans.

And it also turns up a report from the Inspector General’s office at the federal Department of Health and Human Services.

And if you’ve got regular insurance, you may be familiar with what’s called “prior authorization.” That’s when your provider needs to get the insurance company’s OK, their authorization, before going ahead with whatever they think you need … a test, a procedure, a prescription.

And sometimes the insurer issues a denial. They say no.

The Inspector General’s report looked at a random sample of denials by Medicare Advantage plans. They found one out of every eight denials was for care traditional Medicare totally covers.

Which, you know, as you get older, if you got sick, you could have eight of these requests in a month.

Sarah Jane started talking with patients.

Sarah Jane Tribble: I called one gentleman in Washington state, and he wanted out of his Medicare Advantage plan and he couldn’t get out.

Dan: That gentleman is Rick Timmins.

Rick Timmins: I’m a retired veterinarian. I’m living on Whidbey Island in Washington, which is just north and west of Seattle.

Dan: Ooo, wow! So, is your life just a succession of paddling trips …

Rick Timmins: Ha ha ha ha ha ha.

Dan: and swims in the sound?

Rick Timmins: Yes, sort of. Although the water is a little bit too cold for me to swim in. So, it’s kayaks when we get out into the water.

Dan: Rick signed up for Medicare Advantage in 2016 after attending an informational seminar run by an insurance agent.

Rick Timmins: … nice guy, and he said, you know, the best thing to do is to get a Medicare Advantage plan because they cover everything, and it’s, it’s far less expensive than traditional Medicare,

Dan: OK, why would that guy say Medicare Advantage is far less expensive than traditional Medicare? I mean, for one, a lot of us think Medicare’s gonna be free.

And even if it’s not, why should … I mean, how could … one kind of Medicare be more expensive than another?

We’re gonna have a lot of details on this later, but here let’s just get into the difference between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare. Traditional Medicare is run by the government. Government pays all the bills.

BUT traditional medicare only pays 80 percent of everything and you’re on the hook for the other 20 percent. There’s no out-of-pocket limit. Let’s bring back Sarah Jane Tribble to briefly say what that means:

Sarah Jane Tribble: You could pay out the wazoo. It could bankrupt you.

Dan: Out the wazoo. Because you know: Medical bills, hospital bills … they can get into the tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands of dollars. Twenty percent of that is paying out the wazoo.

To avoid that risk, if you’re on traditional Medicare you basically need another insurance policy — a supplement, often called Medigap — like it covers the gaps that traditional Medicare leaves.

Some people get Medigap from their old employers. But most people have to pay for it. It can get expensive.

Medicare Advantage plans, plans run by private insurance companies, DO have an out of pocket limit. You don’t have to buy a supplement. That’s an advantage.

Also, there are things traditional Medicare doesn’t pay for — like dental care, and glasses, and hearing aids. Medicare Advantage plans generally DO cover those things.

And as Rick recalls, the insurance agent pushed Medicare Advantage kinda hard.

Rick Timmins: Basically what he said was, yeah, if you want to sign up for traditional Medicare, I can help you for that, but if you want Medicare Advantage, which is a much better program…

Dan: Then sign right here. So Rick did. Fast forward five years. Rick’s wife notices a little bump on his ear.

Rick Timmins: She said, you should get that looked at. I have a family history of melanoma. My two sisters have had melanoma.

Dan: Rick says he saw his primary care doc, then started trying to get his insurance company’s promise that seeing a specialist would be covered. He says he called and called, over more than six months.

Rick Timmins: It was not a fun time. I mean, I didn’t know what it was, but I knew that it was growing and it was sore and you know, I was frightened. It’s like you can’t think about anything else when you’re wondering about what’s happening with this little lump.

Dan: Rick says when he did get seen, the thing was the size of a dime. They found it was malignant, cut his earlobe off, and scanned his lymph nodes. They were clean, but he spent a year on immunotherapy. Now he says he’s getting scans every six months.

Sarah Jane Tribble asked Rick’s insurance company about all this. They said they wouldn’t comment on his case.

Meanwhile, Rick says he’s had enough of Medicare Advantage. On traditional Medicare, you don’t need anybody’s OK to go see a specialist. You just go.

But of course to switch to traditional Medicare, Rick would need a supplement, a Medigap policy.

Rick Timmins: Otherwise, uh, you’re just forking out thousands of dollars if you have any issues.

Dan: Because you’re on the hook for 20 percent of everything. No out of pocket limit. Paying out the wazoo.

But Rick doesn’t think he can get a medigap policy. Because in most states — including Washington, where Rick lives — insurance companies don’t have to issue you a Medigap policy if you have pre-existing conditions.

Not unless you sign up for it when you FIRST enroll in Medicare.

Rick Timmins: The insurance companies can tell me, no, we don’t want to insure you. You’ve had too many issues. Look, you had a knee replaced. You had cancer.

Dan: This is what made Rick’s story, and the whole Medicare situation, so striking to Sarah Jane Tribble.

Sarah Jane Tribble: It’s sort of shocking, actually, right? The Affordable Care Act passes and makes it so that everybody with pre-existing conditions can get insurance no matter what, but it leaves out the people who might need that the most, who are 65 and older.

Dan: Four states have laws that do require Medigap insurers to take everybody. But only four.

Sarah Jane Tribble: If you’re Rick in Washington state, you could get rejected.

Dan: I talked to someone else who would like do-overs on signing up for Medicare Advantage. In the 1970s, in his 20s, Robert Wolpa was a professional musician, a guitar player.

Robert Wolpa: Played in bands up and down the west coast. Went to Canada with an Elvis act. It was really a lot of fun.

Dan: And he worked in call centers for decades. When he turned 65, he says he got inundated with ads and calls and flyers.

Robert Wolpa: I got one of the mailers says have a free dinner on us. And we’ll teach you all about Medicare, the ins and outs of Medicare.

Dan: He went, and got what he thinks of in retrospect as a hard-sell pitch for Medicare Advantage, which he bought. And, over time, he’s gotten disillusioned.

He says, you know, it’s one thing to have to call to get a pre-authorization or a referral. “Is this doctor covered? No. Oh okay. Which doctor is covered?” It’s a lot of calls. And then there’s the difficulty of getting through the calls.

Robert Wolpa: It got harder and harder and more frustrating, talking to some of these people who didn’t know what they were doing. I mean and I’ve been a call center guy too for most of my life but these poor people. I mean they are so undertrained and underpaid.

Dan: At least, that’s the impression Robert gets, as a guy who spent years working in call centers.

Robert has priced out a Medigap plan. Because he’s got pre-existing conditions — HIV, a pacemaker — it would be expensive: four hundred seventy nine dollars. Which is almost a third of what he gets from social security.

Robert Wolpa: And I said, okay. Next option.

Dan: I suggest maybe his work background gives him an advantage in jumping through hoops, like making all those calls: both knowing how to navigate, and having empathy that could help him keep his blood pressure from spiking too hard. He says, yeah, up to a point … For now.

Robert Wolpa: And I think to myself, you know, I’m 71. I just turned 71 in November and I’m, I’m a little, I’ve got, I’ve got a little of the HIV cognizant crap. Like my, my short term memory is gone.

Dan: After talking with Robert, this part really gave me pause. I mean, dealing with insurance companies and all the attendant hassles is hard work, right?

It’s not the kind of job I’d wish on somebody as they get older and start slowing down.

And it could be a job that increasing numbers of people are signing up for: Last year the number of people in Medicare Advantage plans became the majority of people on Medicare.

Alright, I may have scared the bejesus out of you. I’m a little scared myself.

But I’ve got some super-practical information coming your way. I talked with one of THE best people in the country to find out: What should I know BEFORE it’s time to sign up for Medicare?

Turns out the answer is … A LOT. That’s next.

This episode of “An Arm and a Leg” is produced in partnership with KFF Health News. That’s a nonprofit newsroom covering health care in America. Their reporters, like Sarah Jane Tribble, are amazing. I’m honored to work with them.

OK, so, if you want traditional Medicare, you pretty much need to choose it when you first sign up for Medicare.

And signing up for Medicare turns out to involve a LOT of choices, and a lot of different price tags.

And some big potential pitfalls. It is wild, the things I’ve learned.

I found maybe the best person in the country to learn from.

Sarah Murdoch: My name is Sarah Murdoch. I’m the Director of Client Services at the Medicare Rights Center, and we’re a national non profit that assists with Really any Medicare issue that you could conceive of and we serve like a massive quantity of people on our helpline, about 20, 000 people in a year.

Dan: What would you want people to know when they’re like, say, I don’t know, 64, uh, about the choices there? Because I think a lot of us think, like, “Oh, I’m going to turn 65. I’m going to call the federal government or maybe they’ll call me and I never have to think about health insurance again, or healthcare, or you know, paying these ridiculous prices.” And I think that’s not exactly true. Right?

Sarah Murdoch: To start off, they’re not going to call you.

Dan: And not only do I have to call THEM, I have to do it on time. Apparently, I get a seven month window — like three and a half months on either side of my 65th birthday. And I better not miss it.

Because if I do, well, number one: I have to wait until the following January to sign up. And till then, I better have some OTHER health insurance. Because no Medicare for me.

And not only that: When I do sign up, I’m gonna have to pay a penalty. When Sarah told me this, I was like, “are you kidding me?”

Sarah Murdoch: No, I wish I was kidding, but unfortunately, unfortunately not. So yeah, there are very stringent, kind of, enrollment windows that people need to stick to.

Dan: I kind of couldn’t take it all in at once. I was like, “So either I have to wait, or else I have to pay?” Is that it? Sarah’s like, “no, dummy.”

Sarah Murdoch: You would have to wait AND you would have to pay. So, …

Dan: You’re going to charge me for not having Medicare? That sounds awful.

Sarah Murdoch: I love talking to people like you said when they’re 64 because you can kind of head off the pitfalls before they happen.

Dan: Oh, get this: The penalty is not a one-time late fee. It bumps up what you pay for the rest of your life.

Holy crap! I had done some homework before talking with Sarah, but I had not seen that one coming at all. So yeah. Don’t miss that deadline! And about the rest, the part I thought I’d done my homework on, boy did Sarah fill in a lot of blanks.

So, just to get started, here’s the big picture: Medicare is alphabet soup. There’s part A, that covers hospital bills. There’s part B, that covers doctor visits. And there’s part D, for drugs.

What’s part C, you’re asking? Oh, that’s Medicare Advantage. If you’ve got that, it basically takes over for A, B and– a lot of the time, D.

And let’s say you don’t want to go with Medicare Advantage when you first sign up for Medicare, because for most people, this is like your one shot at getting traditional Medicare, accepted just about everywhere, no questions asked.

Then, you’ll need to buy a Medigap supplement, so you don’t end up paying out the wazoo if you run into health problems– because traditional Medicare only pays 80 percent.

But no matter what you pick– Medicare Advantage or traditional Medicare … it’s gonna cost you. As we heard from Sarah right at the top of this episode…

Sarah Murdoch: I think a lot of people think, Oh, Medicare is going to be free, it unfortunately is not.

Dan: Yeah, so each part has its own price tag … Or tags. Sarah walked me through it.

And actually, the very first step involves some GOOD news.

Sarah Murdoch: Part A, which is hospital and inpatient coverage is free for most people.

Dan: So, if you’ve paid into social security and medicare for ten years, that’s you. So, great.

And unfortunately, that’s where the easy, simple part… ends.

Next, we move on to Part B — doctor bills. Outpatient stuff.

Sarah Murdoch: Part B has a monthly premium, uh, of $174… let me just get the exact, it’s $174 and change,

Dan: A hundred seventy-four dollars and seventy cents.

And important to note: Picking a Medicare Advantage plan does NOT mean you skip paying this part B premium, this 174 dollars and seventy cents. It applies to pretty much everybody.

And folks with higher incomes — starting at 103,000 dollars — can pay more.

OK, that’s part B. Doctor visits. On to part D for drugs.

Fun fact: This is 100 percent run by private insurance companies, actually.

Which, among other things, means it involves shopping for a plan. Every year.

Sarah Murdoch: Those plans and their premiums change year to year. In New York, like, we would see them ranging from anywhere from like $3 monthly premium to $120. So all over the place.

Dan: $3 sounds good, but I’m guessing there’s a catch.

Sarah Murdoch: Yes, so not every plan is identical.

Dan: Some Part D plans cover more drugs than others. Some leave you paying more for the drugs they do cover. Which one is a good deal will depend on what meds you need.

Ugh, sounds fun, right? Well, Sarah tells me there’s actually a bit of good news here, because we’re not on our own with this.

Sarah Murdoch: Medicare does, on medicare.gov, have a really great tool called “plan finder” where people can enter their medications. It sort of matches up your medications with the plans that cover them in the most affordable way.

Dan: This is a huge relief, because shopping on my own? Yeesh. It looks like there are 21 different Part D plans in my area, so comparing all of them would be a big job.

OK! Now I’ve got Parts A, B, and D. I’m on the hook for, well start with $174.70, plus however much for drugs.

And if I still want traditional Medicare — just about everyone takes it, hardly any pre-authorizations to worry about — I still need a Medigap plan. Also called a supplement. And, again, now I’m shopping for insurance from private companies.

And guess what? We’ve got a whole new bowl of alphabet soup!

Sarah Murdoch: Yeah. So there’s 10 Medigaps. They all have a letter.

Dan: Yeah and each letter has its own set of benefits and exclusions —some have higher deductibles, others cover some extras, but they’re all supposed to protect you from paying out the wazoo.

So for example, Plan G is the most comprehensive, and the most expensive. And of course, once I’ve picked a letter, I’m sifting through however-many companies offer any given plan in my area.

Where I live, in Illinois, it looks like there are 57 Plan G’s on offer. Prices: A hundred thirty bucks to four sixty four.

But here’s another little bit of good news for us. Because Sarah has a super important tip.

Sarah Murdoch: I think it is very important for people to keep in mind there that all the G’s are identical, right? A G offered by company 1 that’s $500, versus the G offered by company 2 that’s $300, have identical benefits, so there’s no reason to pick the, um, more expensive.

Dan: I ask Sarah: Wait. How are any of these companies getting away with charging more for the exact same thing? Like, why would anybody ever choose the more expensive one? She’s like, maybe they just don’t know any better.

Sarah Murdoch: Maybe they had that company, you know, when they were working and they have, you know, preconceived notions about it.

Dan: So when people call the helpline, Sarah and her colleagues tell them …

Sarah Murdoch: Pick one that’s the most affordable. Don’t make some other selection for whatever reason you might imagine in your head.

Dan: So of course it turns out in the case of Plan G, which just happens to be the example Sarah’s using, there IS a caveat: In some states, there are Plan G’s sold with a high deductible and lower premiums. Okay, more to watch out for. But in general, this is some really good advice right here.

All of this leaves me with a big take-away:

Medicare is not free. There’s that 174 seventy for the Part B premium … and then you may be looking at a bunch of money on top of that, for a Medigap plan.

Or, if you go with Medicare Advantage and avoid paying for a Medigap plan, you are looking at dealing with private health insurance companies that we all love so much.

All the shopping for a plan: “Do I get an HMO? A PPO? What’s the difference again?”

And then all the questions, all the run-arounds, all year round: “Is my doctor covered? Is my doctor still covered this year? Is the company gonna approve the care my doctor says I need? If they don’t, what the hell am I gonna do?”

All of it left my colleague Sarah Jane Tribble pretty ticked off.

Sarah Jane Tribble: The thing that blew my mind is how expensive it is to have any form of Medicare, right? It’s not a free ticket for your health care. This is to me, the most outrageous thing that you’re going into retirement, you’ve lived your life, and America is supposed to give you this promise of Medicare, and then the promise is actually hundreds of dollars a month.

Dan: Or you can save some money by signing up for Medicare Advantage, and hope it works out for you.

And hey: It does work for some people. My mom’s on a Medicare Advantage plan — she’s 93 and definitely sees a few doctors — and she’s got no complaints.

Here’s Sarah Murdoch from the Medicare Rights Center:

Sarah Murdoch: When people ask, I think often, like, which one is better? It’s like, that’s, that’s not … I can’t answer that because people’s needs are different. People’s doctors are different. Where they live and their access to different services might be different. If you’re in a plan that all your doctors take, then that’s great. You can save some money that way too on those premiums.

Dan: And hope the insurance company doesn’t change the deal next year. And that your doctors don’t decide to leave the plan.

OK, I’m not trying to freak you out — or myself. And I actually have some good news, thanks to Sarah Murdoch.

Because: We’ve covered a lot of ground on what you should know about Medicare. But holy crap, there is SO much more to know. Medigap plans are regulated by states– that’s 50 different setups right there. Not to mention the ten different flavors of Medigap. And all the kajillion and one different Medicare Advantage plans out there.

And there’s deals we haven’t talked about too. Some people with low incomes qualify for Medicaid, which kind of serves as a Medigap. Some people can get government subsidies to cover that Medicare Part B premium. And, again, all of this is state-by-state: 50 different deals.

So if you’re looking at actually signing up for Medicare, you’re gonna have a lot more questions than I can start to answer here.

And the good news is: You don’t have to go to an insurance broker, like Rick and Rob did, and hope they steer you right instead of, you know, chasing a higher commission.

Sarah Murdoch says every state has an agency you can call. They’re called SHIPS — for State Health Insurance Assistance Programs — the A is silent, I guess. And their job is to give unbiased advice.

If you’re in New York, you might even end up talking with Sarah or one of her colleagues.

Sarah Murdoch: The SHIPS don’t get anything. They don’t have any financial incentive. We participate in the New York ship, like I don’t care what plan you pick. I just want to help you pick something that is going to work for you. And that may be original Medicare with a Medigap and Part D. It might be a Medicare Advantage plan. It might be, you know, Medicare and Medicaid.

Dan: So if this episode is pitched at someone who’s at or approaching age 64, the bottom line is like, go get on a ship. Go sail on a ship. Is that right?

Sarah Murdoch: Yeah. There’s a central website, shiphelp. org, where you can just click on your state and it will kind of direct you to the phone number to call. So, they’re there as a resource.

This was a LOT. Let’s just review:

First: Medicare isn’t free. Got it.

Second: Don’t forget to sign up on time! You could end up paying a late fee every month for the rest of your life.

“An Arm and a Leg” is a co-production of KFF Health News and Public Road Productions.

To keep in touch with “An Arm and a Leg,” subscribe to the newsletter. You can also follow the show on Facebook and X, formerly known as Twitter. And if you’ve got stories to tell about the health care system, the producers would love to hear from you.

To hear all KFF Health News podcasts, click here.

And subscribe to “An Arm and a Leg” on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

——————————

By: Dan Weissmann

Title: An Arm and a Leg: The Medicare Episode

Sourced From: kffhealthnews.org/news/podcast/the-medicare-episode/

Published Date: Mon, 11 Mar 2024 09:00:00 +0000

Kaiser Health News

US Judge Names Receiver To Take Over California Prisons’ Mental Health Program

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — A judge has initiated a federal court takeover of California’s troubled prison mental health system by naming the former head of the Federal Bureau of Prisons to serve as receiver, giving her four months to craft a plan to provide adequate care for tens of thousands of prisoners with serious mental illness.

Senior U.S. District Judge Kimberly Mueller issued her order March 19, identifying Colette Peters as the nominated receiver. Peters, who was Oregon’s first female corrections director and known as a reformer, ran the scandal-plagued federal prison system for 30 months until President Donald Trump took office in January. During her tenure, she closed a women’s prison in Dublin, east of Oakland, that had become known as the “rape club.”

Michael Bien, who represents prisoners with mental illness in the long-running prison lawsuit, said Peters is a good choice. Bien said Peters’ time in Oregon and Washington, D.C., showed that she “kind of buys into the fact that there are things we can do better in the American system.”

“We took strong objection to many things that happened under her tenure at the BOP, but I do think that this is a different job and she’s capable of doing it,” said Bien, whose firm also represents women who were housed at the shuttered federal women’s prison.

California corrections officials called Peters “highly qualified” in a statement, while Gov. Gavin Newsom’s office did not immediately comment. Mueller gave the parties until March 28 to show cause why Peters should not be appointed.

Peters is not talking to the media at this time, Bien said. The judge said Peters is to be paid $400,000 a year, prorated for the four-month period.

About 34,000 people incarcerated in California prisons have been diagnosed with serious mental illnesses, representing more than a third of California’s prison population, who face harm because of the state’s noncompliance, Mueller said.

Appointing a receiver is a rare step taken when federal judges feel they have exhausted other options. A receiver took control of Alabama’s correctional system in 1976, and they have otherwise been used to govern prisons and jails only about a dozen times, mostly to combat poor conditions caused by overcrowding. Attorneys representing inmates in Arizona have asked a judge to take over prison health care there.

Mueller’s appointment of a receiver comes nearly 20 years after a different federal judge seized control of California’s prison medical system and installed a receiver, currently J. Clark Kelso, with broad powers to hire, fire, and spend the state’s money.

California officials initially said in August that they would not oppose a receivership for the mental health program provided that the receiver was also Kelso, saying then that federal control “has successfully transformed medical care” in California prisons. But Kelso withdrew from consideration in September, as did two subsequent candidates. Kelso said he could not act “zealously and with fidelity as receiver in both cases.”

Both cases have been running for so long that they are now overseen by a second generation of judges. The original federal judges, in a legal battle that reached the U.S. Supreme Court, more than a decade ago forced California to significantly reduce prison crowding in a bid to improve medical and mental health care for incarcerated people.

State officials in court filings defended their improvements over the decades. Prisoners’ attorneys countered that treatment remains poor, as evidenced in part by the system’s record-high suicide rate, topping 31 suicides per 100,000 prisoners, nearly double that in federal prisons.

“More than a quarter of the 30 class-members who died by suicide in 2023 received inadequate care because of understaffing,” prisoners’ attorneys wrote in January, citing the prison system’s own analysis. One prisoner did not receive mental health appointments for seven months “before he hanged himself with a bedsheet.”

They argued that the November passage of a ballot measure increasing criminal penalties for some drug and theft crimes is likely to increase the prison population and worsen staffing shortages.

California officials argued in January that Mueller isn’t legally justified in appointing a receiver because “progress has been slow at times but it has not stalled.”

Mueller has countered that she had no choice but to appoint an outside professional to run the prisons’ mental health program, given officials’ intransigence even after she held top officials in contempt of court and levied fines topping $110 million in June. Those extreme actions, she said, only triggered more delays.

The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals on March 19 upheld Mueller’s contempt ruling but said she didn’t sufficiently justify calculating the fines by doubling the state’s monthly salary savings from understaffing prisons. It upheld the fines to the extent that they reflect the state’s actual salary savings but sent the case back to Mueller to justify any higher penalty.

Mueller had been set to begin additional civil contempt proceedings against state officials for their failure to meet two other court requirements: adequately staffing the prison system’s psychiatric inpatient program and improving suicide prevention measures. Those could bring additional fines topping tens of millions of dollars.

But she said her initial contempt order has not had the intended effect of compelling compliance. Mueller wrote as far back as July that additional contempt rulings would also be likely to be ineffective as state officials continued to appeal and seek delays, leading “to even more unending litigation, litigation, litigation.”

She went on to foreshadow her latest order naming a receiver in a preliminary order: “There is one step the court has taken great pains to avoid. But at this point,” Mueller wrote, “the court concludes the only way to achieve full compliance in this action is for the court to appoint its own receiver.”

This article was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

If you or someone you know may be experiencing a mental health crisis, contact the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline by dialing or texting “988.”

The post US Judge Names Receiver To Take Over California Prisons’ Mental Health Program appeared first on kffhealthnews.org

Kaiser Health News

Amid Plummeting Diversity at Medical Schools, a Warning of DEI Crackdown’s ‘Chilling Effect’

The Trump administration’s crackdown on DEI programs could exacerbate an unexpectedly steep drop in diversity among medical school students, even in states like California, where public universities have been navigating bans on affirmative action for decades. Education and health experts warn that, ultimately, this could harm patient care.

Since taking office, President Donald Trump has issued a handful of executive orders aimed at terminating all diversity, equity, and inclusion, or DEI, initiatives in federally funded programs. And in his March 4 address to Congress, he described the Supreme Court’s 2023 decision banning the consideration of race in college and university admissions as “brave and very powerful.”

Last month, the Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights — which lost about 50% of its staff in mid-March — directed schools, including postsecondary institutions, to end race-based programs or risk losing federal funding. The “Dear Colleague” letter cited the Supreme Court’s decision.

Paulette Granberry Russell, president and CEO of the National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education, said that “every utterance of ‘diversity’ is now being viewed as a violation or considered unlawful or illegal.” Her organization filed a lawsuit challenging Trump’s anti-DEI executive orders.

While California and eight other states — Arizona, Florida, Idaho, Michigan, Nebraska, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, and Washington — had already implemented bans of varying degrees on race-based admissions policies well before the Supreme Court decision, schools bolstered diversity in their ranks with equity initiatives such as targeted scholarships, trainings, and recruitment programs.

But the court’s decision and the subsequent state-level backlash — 29 states have since introduced bills to curb diversity initiatives, according to data published by the Chronicle of Higher Education — have tamped down these efforts and led to the recent declines in diversity numbers, education experts said.

After the Supreme Court’s ruling, the numbers of Black and Hispanic medical school enrollees fell by double-digit percentages in the 2024-25 school year compared with the previous year, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges. Black enrollees declined 11.6%, while the number of new students of Hispanic origin fell 10.8%. The decline in enrollment of American Indian or Alaska Native students was even more dramatic, at 22.1%. New Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander enrollment declined 4.3%.

“We knew this would happen,” said Norma Poll-Hunter, AAMC’s senior director of workforce diversity. “But it was double digits — much larger than what we anticipated.”

The fear among educators is the numbers will decline even more under the new administration.

At the end of February, the Education Department launched an online portal encouraging people to “report illegal discriminatory practices at institutions of learning,” stating that students should have “learning free of divisive ideologies and indoctrination.” The agency later issued a “Frequently Asked Questions” document about its new policies, clarifying that it was acceptable to observe events like Black History Month but warning schools that they “must consider whether any school programming discourages members of all races from attending.”

“It definitely has a chilling effect,” Poll-Hunter said. “There is a lot of fear that could cause institutions to limit their efforts.”

Numerous requests for comment from medical schools about the impact of the anti-DEI actions went unreturned. University presidents are staying mum on the issue to protect their institutions, according to reporting from The New York Times.

Utibe Essien, a physician and UCLA assistant professor, said he has heard from some students who fear they won’t be considered for admission under the new policies. Essien, who co-authored a study on the effect of affirmative action bans on medical schools, also said students are worried medical schools will not be as supportive toward students of color as in the past.

“Both of these fears have the risk of limiting the options of schools folks apply to and potentially those who consider medicine as an option at all,” Essien said, adding that the “lawsuits around equity policies and just the climate of anti-diversity have brought institutions to this place where they feel uncomfortable.”

In early February, the Pacific Legal Foundation filed a lawsuit against the University of California-San Francisco’s Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland over an internship program designed to introduce “underrepresented minority high school students to health professions.”

Attorney Andrew Quinio filed the suit, which argues that its plaintiff, a white teenager, was not accepted to the program after disclosing in an interview that she identified as white.

“From a legal standpoint, the issue that comes about from all this is: How do you choose diversity without running afoul of the Constitution?” Quinio said. “For those who want diversity as a goal, it cannot be a goal that is achieved with discrimination.”

UC Health spokesperson Heather Harper declined to comment on the suit on behalf of the hospital system.

Another lawsuit filed in February accuses the University of California of favoring Black and Latino students over Asian American and white applicants in its undergraduate admissions. Specifically, the complaint states that UC officials pushed campuses to use a “holistic” approach to admissions and “move away from objective criteria towards more subjective assessments of the overall appeal of individual candidates.”

The scrutiny of that approach to admissions could threaten diversity at the UC-Davis School of Medicine, which for years has employed a “race-neutral, holistic admissions model” that reportedly tripled enrollment of Black, Latino, and Native American students.

“How do you define diversity? Does it now include the way we consider how someone’s lived experience may be influenced by how they grew up? The type of school, the income of their family? All of those are diversity,” said Granberry Russell, of the National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education. “What might they view as an unlawful proxy for diversity equity and inclusion? That’s what we’re confronted with.”

California Attorney General Rob Bonta, a Democrat, recently joined other state attorneys general to issue guidance urging that schools continue their DEI programs despite the federal messaging, saying that legal precedent allows for the activities. California is also among several states suing the administration over its deep cuts to the Education Department.

If the recent decline in diversity among newly enrolled students holds or gets worse, it could have long-term consequences for patient care, academic experts said, pointing toward the vast racial disparities in health outcomes in the U.S., particularly for Black people.

A higher proportion of Black primary care doctors is associated with longer life expectancy and lower mortality rates among Black people, according to a 2023 study published by the JAMA Network.

Physicians of color are also more likely to build their careers in medically underserved communities, studies have shown, which is increasingly important as the AAMC projects a shortage of up to 40,400 primary care doctors by 2036.

“The physician shortage persists, and it’s dire in rural communities,” Poll-Hunter said. “We know that diversity efforts are really about improving access for everyone. More diversity leads to greater access to care — everyone is benefiting from it.”

This article was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

The post Amid Plummeting Diversity at Medical Schools, a Warning of DEI Crackdown’s ‘Chilling Effect’ appeared first on kffhealthnews.org

Kaiser Health News

Tribal Health Leaders Say Medicaid Cuts Would Decimate Health Programs

As Congress mulls potentially massive cuts to federal Medicaid funding, health centers that serve Native American communities, such as the Oneida Community Health Center near Green Bay, Wisconsin, are bracing for catastrophe.

That’s because more than 40% of the about 15,000 patients the center serves are enrolled in Medicaid. Cuts to the program would be detrimental to those patients and the facility, said Debra Danforth, the director of the Oneida Comprehensive Health Division and a citizen of the Oneida Nation.

“It would be a tremendous hit,” she said.

The facility provides a range of services to most of the Oneida Nation’s 17,000 people, including ambulatory care, internal medicine, family practice, and obstetrics. The tribe is one of two in Wisconsin that have an “open-door policy,” Danforth said, which means that the facility is open to members of any federally recognized tribe.

But Danforth and many other tribal health officials say Medicaid cuts would cause service reductions at health facilities that serve Native Americans.

Indian Country has a unique relationship to Medicaid, because the program helps tribes cover chronic funding shortfalls from the Indian Health Service, the federal agency responsible for providing health care to Native Americans.

Medicaid has accounted for about two-thirds of third-party revenue for tribal health providers, creating financial stability and helping facilities pay operational costs. More than a million Native Americans enrolled in Medicaid or the closely related Children’s Health Insurance Program also rely on the insurance to pay for care outside of tribal health facilities without going into significant medical debt. Tribal leaders are calling on Congress to exempt tribes from cuts and are preparing to fight to preserve their access.

“Medicaid is one of the ways in which the federal government meets its trust and treaty obligations to provide health care to us,” said Liz Malerba, director of policy and legislative affairs for the United South and Eastern Tribes Sovereignty Protection Fund, a nonprofit policy advocacy organization for 33 tribes spanning from Texas to Maine. Malerba is a citizen of the Mohegan Tribe.

“So we view any disruption or cut to Medicaid as an abrogation of that responsibility,” she said.

Tribes face an arduous task in providing care to a population that experiences severe health disparities, a high incidence of chronic illness, and, at least in western states, a life expectancy of 64 years — the lowest of any demographic group in the U.S. Yet, in recent years, some tribes have expanded access to care for their communities by adding health services and providers, enabled in part by Medicaid reimbursements.

During the last two fiscal years, five urban Indian organizations in Montana saw funding growth of nearly $3 million, said Lisa James, director of development for the Montana Consortium for Urban Indian Health, during a webinar in February organized by the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families and the National Council of Urban Indian Health.

The increased revenue was “instrumental,” James said, allowing clinics in the state to add services that previously had not been available unless referred out for, including behavioral health services. Clinics were also able to expand operating hours and staffing.

Montana’s five urban Indian clinics, in Missoula, Helena, Butte, Great Falls, and Billings, serve 30,000 people, including some who are not Native American or enrolled in a tribe. The clinics provide a wide range of services, including primary care, dental care, disease prevention, health education, and substance use prevention.

James said Medicaid cuts would require Montana’s urban Indian health organizations to cut services and limit their ability to address health disparities.

American Indian and Alaska Native people under age 65 are more likely to be uninsured than white people under 65, but 30% rely on Medicaid compared with 15% of their white counterparts, according to KFF data for 2017 to 2021. More than 40% of American Indian and Alaska Native children are enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP, which provides health insurance to kids whose families are not eligible for Medicaid. KFF is a health information nonprofit that includes KFF Health News.

A Georgetown Center for Children and Families report from January found the share of residents enrolled in Medicaid was higher in counties with a significant Native American presence. The proportion on Medicaid in small-town or rural counties that are mostly within tribal statistical areas, tribal subdivisions, reservations, and other Native-designated lands was 28.7%, compared with 22.7% in other small-town or rural counties. About 50% of children in those Native areas were enrolled in Medicaid.

The federal government has already exempted tribes from some of Trump’s executive orders. In late February, Department of Health and Human Services acting general counsel Sean Keveney clarified that tribal health programs would not be affected by an executive order that diversity, equity, and inclusion government programs be terminated, but that the Indian Health Service is expected to discontinue diversity and inclusion hiring efforts established under an Obama-era rule.

HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. also rescinded the layoffs of more than 900 IHS employees in February just hours after they’d received termination notices. During Kennedy’s Senate confirmation hearings, he said he would appoint a Native American as an assistant HHS secretary. The National Indian Health Board, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit that advocates for tribes, in December endorsed elevating the director of the Indian Health Service to assistant secretary of HHS.

Jessica Schubel, a senior health care official in Joe Biden’s White House, said exemptions won’t be enough.

“Just because Native Americans are exempt doesn’t mean that they won’t feel the impact of cuts that are made throughout the rest of the program,” she said.

State leaders are also calling for federal Medicaid spending to be spared because cuts to the program would shift costs onto their budgets. Without sustained federal funding, which can cover more than 70% of costs, state lawmakers face decisions such as whether to change eligibility requirements to slim Medicaid rolls, which could cause some Native Americans to lose their health coverage.

Tribal leaders noted that state governments do not have the same responsibility to them as the federal government, yet they face large variations in how they interact with Medicaid depending on their state programs.

President Donald Trump has made seemingly conflicting statements about Medicaid cuts, saying in an interview on Fox News in February that Medicaid and Medicare wouldn’t be touched. In a social media post the same week, Trump expressed strong support for a House budget resolution that would likely require Medicaid cuts.

The budget proposal, which the House approved in late February, requires lawmakers to cut spending to offset tax breaks. The House Committee on Energy and Commerce, which oversees spending on Medicaid and Medicare, is instructed to slash $880 billion over the next decade. The possibility of cuts to the program that, together with CHIP, provides insurance to 79 million people has drawn opposition from national and state organizations.

The federal government reimburses IHS and tribal health facilities 100% of billed costs for American Indian and Alaska Native patients, shielding state budgets from the costs.

Because Medicaid is already a stopgap fix for Native American health programs, tribal leaders said it won’t be a matter of replacing the money but operating with less.

“When you’re talking about somewhere between 30% to 60% of a facility’s budget is made up by Medicaid dollars, that’s a very difficult hole to try and backfill,” said Winn Davis, congressional relations director for the National Indian Health Board.

Congress isn’t required to consult tribes during the budget process, Davis added. Only after changes are made by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and state agencies are tribes able to engage with them on implementation.

The amount the federal government spends funding the Native American health system is a much smaller portion of its budget than Medicaid. The IHS projected billing Medicaid about $1.3 billion this fiscal year, which represents less than half of 1% of overall federal spending on Medicaid.

“We are saving more lives,” Malerba said of the additional services Medicaid covers in tribal health care. “It brings us closer to a level of 21st century care that we should all have access to but don’t always.”

This article was published with the support of the Journalism & Women Symposium (JAWS) Health Journalism Fellowship, assisted by grants from The Commonwealth Fund.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

The post Tribal Health Leaders Say Medicaid Cuts Would Decimate Health Programs appeared first on kffhealthnews.org

-

Mississippi Today7 days ago

Mississippi Today7 days agoLawmakers used to fail passing a budget over policy disagreement. This year, they failed over childish bickering.

-

Mississippi Today7 days ago

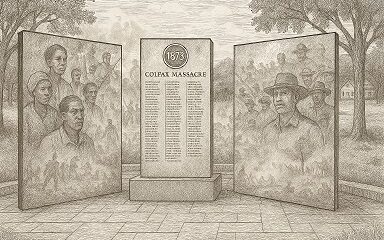

Mississippi Today7 days agoOn this day in 1873, La. courthouse scene of racial carnage

-

Local News7 days ago

Local News7 days agoSouthern Miss Professor Inducted into U.S. Hydrographer Hall of Fame

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days agoFoley man wins Race to the Finish as Kyle Larson gets first win of 2025 Xfinity Series at Bristol

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days agoFederal appeals court upholds ruling against Alabama panhandling laws

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Texas News Feed7 days ago1 dead after 7 people shot during large gathering at Crosby gas station, HCSO says

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days agoJacksonville University only school with 2 finalist teams in NASA’s 2025 Human Lander Challenge

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days agoInsects as food? ‘We are largely ignoring the largest group of organisms on earth’