Mississippi Today

A president from Georgia, a journalist from Mississippi, and an iconic photo

Among the many breathtaking mementos on display at Curtis Wilkie’s home in Oxford is a photograph that students of American history and political journalism know well.

The vertical black-and-white image, captured by Associated Press photographer Peter Bregg, shows former President Jimmy Carter, arms extended in the air with his eyes closed and face clinched, colliding with another man while catching a softball.

The other man in the photo is Mississippi’s most accomplished journalist.

The caption of the photo, which ran on front pages across America the next day, reads: “Democratic presidential nominee Jimmy Carter collides with Boston Globe reporter Curtis Wilkie during a softball game in Plains, Georgia, July 23, 1976. Carter made the catch and neither he nor Wilkie was injured in the friendly game between the press and the campaign staff.”

Carter, who passed away at age 100 on Sunday, is being eulogized around the world with heart-warming anecdotes that illustrate the former president’s personality and character. This story is worth adding to that collection, but first, a little context is necessary.

Wilkie, who covered eight presidential campaigns during his years as a journalist for The Boston Globe and other papers, was not exactly Carter’s favorite newsman.

Their relationship turned tempestuous early in the 1976 primary. Carter had not been considered among the formidable candidates to win the Democratic nomination let alone the presidency, but some early success in Iowa had pundits beginning to take notice.

Wilkie, a cub reporter at The Boston Globe assigned to cover the peanut farmer from Georgia, flew south in January 1976 ahead of the New Hampshire primary to assess what Peach State politicians thought of him.

“I talked to people like Julian Bond, John Lewis and other civil rights people, but also to these old rednecks in the Georgia legislature,” Wilkie said. “No one on either side had much respect for him. He’d been stubborn and difficult to work with. Even Julian was critical of him. Really just no one in Georgia was very enthusiastic about his candidacy.

“So I put together a story that basically argued that while he was gaining some ground nationally and he had done well in Iowa, he was not universally loved in Georgia. The Globe ran the story on a Sunday, eight columns across the top of page 1. The headline was, ‘Strong at Home, Weak on the Road.’”

Carter, who was working hard at the time to capitalize on the Iowa coverage and grow his political brand in early primary states, seethed over the article.

“The night my story ran, I met Carter’s campaign at the airport in Manchester,” Wilkie recalled. “My friend Jim Wooten of The New York Times came up to me and said, ‘You better watch out, he is on a war path.’ A couple minutes later, sure enough, Carter saw me and got in my face there in the airport lobby. He had perfected this fierce glare with his piercing blue eyes, and he said very sarcastically, ‘Hello, my friend. I’m so glad to see you, my friend. I see you’ve been down in Georgia talking to some of my friends down there. Let me tell you about some of those friends. They’re all a bunch of corrupt legislators who’ve had their heads in the trough of government.’ He just gave me a blistering rebuke and suggested I’d only sought out his enemies for the article. That obviously wasn’t what I did, but it was the first time we ever crossed swords.”

Throughout the 1976 campaign, Carter and Wilkie had numerous other spats.

“It wasn’t like I disliked him or anything. I think it was just typical of conflict that reporters have with the people they cover,” Wilkie said. “He thought that I was a real smart ass, and I have to admit I deliberately gave him a hard time. I didn’t ask a lot of questions, but when I did, they would sometimes be fairly barbed. I was probably the least favorite reporter covering that campaign. We just had a kind of rivalry.”

No moment more appropriately encapsulated that rivalry than the events of election night in November 1976. After hours of watching the returns roll in, Carter had officially won enough states to defeat then-President Gerald Ford. The first state that was called for Carter early in the evening was Massachusetts, home to Wilkie’s employer The Boston Globe. The final state that secured the electoral college victory at 3 a.m. was Mississippi, Wilkie’s home state.

The Carter campaign’s election watch party that night was held in downtown Atlanta, and when the race was called, the campaign rushed to get the president-elect and his motorcade to the airport for an early-morning live interview for The Today Show from Carter’s rural hometown of Plains, Georgia.

We’ll let Wilkie take it from here.

“We didn’t know it, but the press bus got lost from the caravan to get out to the airport from the watch party, so we got there about 15 minutes late,” Wilkie said. “We didn’t know this at the time, but Carter was furious because he was in a hurry to get home to go on the air with The Today Show. He was going to leave the whole press corps in Atlanta, but someone stalled him. I get on the plane while it’s being loaded, and Carter came stomping down the aisle to expedite things. Again, not knowing about the delay or how angry he was, I thought it was a good time to congratulate him.

“I thought I had a cute way to do it. I said, ‘Governor, congratulations. I didn’t have to do much to deliver Massachusetts, but I had to work like hell to get Mississippi.’ He stopped and gave me that piercing glare again, and he was mad. He said to me, ‘If it weren’t for people like you, this election would’ve been over at 9 o’clock last night.’ He turned his back and marched back up to his seat in first class. As he walked away, I said to the rest of my press colleagues gathered there, ‘There goes the biggest asshole I’ve ever known.’ My quote wound up in Rolling Stone the next day, which certainly didn’t do much to endear me to him.”

Back to the iconic softball photo. During the summer of 1976, shortly after Carter won the Democratic nomination, the traveling press corps spent a good bit of time in Plains. Out of boredom, Wilkie said, the reporters began playing pickup softball games at the high school field.

One day, Carter, a noted fan of the Atlanta Braves and of baseball in general, decided to join the reporters on the field for the first time.

“I was a captain for one team, and Rick Kaplan, who was at CBS at the time and later became head of CNN, was choosing for the other team,” Wilkie recalled. “We deliberately didn’t pick Carter until very last — we even chose some women who weren’t even trying to play before we chose him, which I’m sure he loved. So it ends up that he’s on my team. I said, ‘Governor, I suppose you’d like to pitch.’ He of course did want to pitch, so I ran over to play third base.

“The very first pitch of the game, the batter hit a pop fly right to me at third base,” Wilkie continued. “So I’m standing my ground at third waiting to catch this fly ball, and I hear some big feet tromping toward me. Carter had quite large feet, and I could hear them pounding the red clay and getting closer. I knew he was coming, and sure enough, we collided. He snatched the ball away from me right as it was coming down into my glove. I had my arms up, and my elbow jabbed right into his Adam’s apple.

“I said immediately to Carter, ‘Jesus, governor, now I know how Scoop Jackson (U.S. senator from Washington) felt during the primaries.’ He said without hesitating, ‘Ah, it’s just another run-in with The Boston Globe.’ I always thought that was such a great quip.”

After Carter won the presidency, the Globe sent Wilkie to Washington to cover the Carter White House. “Unsurprisingly, I don’t think I got a single one-on-one interview with him that entire term,” Wilkie said with a laugh. “I had a lot less time with him during his years as president than I had when he was still a little-known candidate from Georgia.”

In the years after Carter left the White House, Wilkie would occasionally get dispatched by his Boston Globe editors to write about the former president’s new books or other key developments at the Carter Center in Atlanta. It was those subsequent visits down south, Wilkie said, that he and Carter developed a friendly relationship.

“There were lots of things I respected and admired about him, other things I didn’t,” Wilkie said. “I appreciated the fact that he was a Southerner and kind of brought us out of the dark years of George Wallace. I admired how genuine his faith was to him, and he did a lot of good works. He was gracious to me in those later years, and I think he became a much better person after he left the White House. He was genuine and kind, and he treated me well. We connected over the loss of his brother Billy, who was a good friend of mine.

“When I’d cover the release of his books, I’d always get him to sign them,” Wilkie said. “Even after all those years of rivalry and contention, he would always sign those books to me with, ‘Your friend, Jimmy Carter.’”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

Mississippians honor first Black lawmaker since Reconstruction

Mississippians honor first Black lawmaker since Reconstruction

Former Mississippi Rep. Robert Clark Jr. lay in state Sunday in the Capitol Rotunda as family, friends, officials and fellow citizens paid respect to the first Black legislator in the state since Reconstruction.

Clark, a Holmes County native, was elected to the House in 1967 and served until his retirement in 2004. He was elected speaker pro tempore by the House membership in 1993 and held that second-highest House position until his retirement.

The Senate and House honored the 96-year-old veteran lamaker last week.

“Robert Clark … broke so many barriers in the state of Mississippi with class, resolve and intellect. So he is going to be sorely missed,” Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann said last week.

Hosemann was among those who came Sunday to honor Clark. So did House Speaker Jason White, who like Clark hails from Holmes County.

Clark was the only Black Mississippian serving in the Legislature from until 1976 and was ostracized when first elected, sitting at a desk by himself for years without the traditional deskmates. But he rose to become a respected leader.

An educator when elected to the House, Clark served 10 years as chair of the House Education Committee, including when the historic Education Reform Act of 1982 was passed.

Clark served as the only Black Mississippian serving in the Legislature from 1968 until 1976.

“He was a trailblazer and icon for sure,” White said last week.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

On this day in 1912

March 9, 1912

Charlotta Bass became one of the nation’s first Black female editor-owners. She renamed The California Owl newspaper The California Eagle, and turned it into a hard-hitting publication. She campaigned against the racist film “Birth of a Nation,” which depicted the Ku Klux Klan as heroes, and against the mistreatment of African Americans in World War I.

After the war ended, she fought racism and segregation in Los Angeles, getting companies to end discriminatory practices. She also denounced political brutality, running front-page stories that read, “Trigger-Happy Cop Freed After Slaying Youth.”

When she reported on a KKK plot against Black leaders, eight Klansmen showed up at her offices. She pulled a pistol out of her desk, and they beat a “hasty retreat,”

The New York Times reported. “Mrs. Bass,” her husband told her, “one of these days you are going to get me killed.” She replied, “Mr. Bass, it will be in a good cause.”

In the 1940s, she began her first foray into politics, running for the Los Angeles City Council. In 1951, she sold the Eagle and co-founded Sojourners for Truth and Justice, a Black women’s group. A year later, she became the first Black woman to run for vice president, running on the Progressive Party ticket. Her campaign slogan: “Win or Lose, We Win by Raising the Issues.”

When Kamala Harris became the first Black female vice presidential candidate for a major political party in 2020, Bass’ pioneering steps were recalled.

“Bass would not win,” The Times wrote. “But she would make history, and for a brief time her lifelong fight for equality would enter the national spotlight.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

On this day in 1977

On this day in 1977

March 8, 1977

Henry L. Marsh III became the first Black mayor of the former capital of the Confederacy, Richmond, Virginia.

Growing up in Virginia, he attended a one-room school that had seven grades and one teacher. Afterward, he went to Richmond, where he became vice president of the senior class at Maggie L. Walker High School and president of the student NAACP branch.

When Virginia lawmakers debated whether to adopt “massive resistance,” he testified against that plan and later won a scholarship for Howard University School of Law. He decided to become a lawyer to “help make positive change happen.” After graduating, he helped win thousands of workers their class-actions cases and helped others succeed in fighting segregation cases.

“We were constantly fighting against race prejudice,” he recalled. “For instance, in the case of Franklin v. Giles County, a local official fired all of the black public school teachers. We sued and got the (that) decision overruled.”

In 1966, he was elected to the Richmond City Council and later became the city’s first Black mayor for five years. He inherited a landlocked city that had lost 40% of its retail revenues in three years, comparing it to “taking a wounded man, tying his hands behind his back, planting his feet in concrete and throwing him in the water and saying, ‘OK, let’s see you survive.’”

In the end, he led the city from “acute racial polarization towards a more civil society.” He served as president of the National Black Caucus of Elected Officials and as a member of the board of directors of the National League of Cities.

As an education supporter, he formed the Support Committee for Excellence in the Public Schools. He also hosts the city’s Annual Juneteenth Celebration. The courthouse where he practiced now bears his name and so does an elementary school.

Marsh also worked to bridge the city’s racial divide, creating what is now known as Venture Richmond. He was often quoted as saying, “It doesn’t impress me to say that something has never been done before, because everything that is done for the first time had never been done before.”

He died on Jan. 23, 2025, at the age of 91.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

-

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed5 days agoRemarkable Woman 2024: What Dawn Bradley-Fletcher has been up to over the year

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed2 days ago

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed2 days agoFeed the Children rolls out new program to help Oklahoma families

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed3 days ago

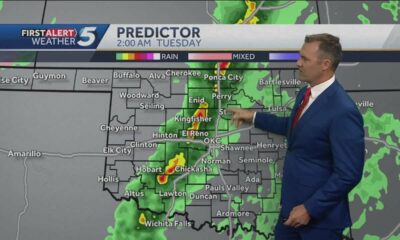

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed3 days agoMarch 6,2025: Rain and snow on the way

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Virginia News Feed7 days agoProbation ends in termination for Va. FEMA worker caught in mass layoffs

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Texas News Feed4 days agoTravis County DA failed to meet deadline to indict murder suspect | FOX 7 Austin

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed7 days agoConfederate monument in Edenton will remain in place for now

-

Mississippi Today5 days ago

Mississippi Today5 days agoKey lawmaker reverses course, passes bill to give poor women earlier prenatal care

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed7 days agoTimeline: Storms bring a risk of tornadoes, damaging winds to Oklahoma (March 3, 2025)