Mississippi Today

A coverage gap Catch-22: To work, Selinda Walker needs health care. To get health care, she needs work.

Forty-seven-year-old Selinda Walker had to move back in with her elderly mother after an untreated and severe case of Graves’ disease left her unable to work and live independently.

As a single, low-income individual with no children, Walker has no path toward health care in the state of Mississippi, which remains one of 10 states in the country not to expand Medicaid. And as lawmakers advocate for work requirements in Medicaid expansion bills, Walker faces a Catch-22: she needs health insurance first to get healthy enough to be able to return to work.

The progression of her disease made it impossible for her to continue working at her jobs in retail and car sales. The worst of her symptoms cause her to suffer dizzy spells and temporarily-paralyzing falls throughout the day, among a slew of other problems.

“I feel like I’m a burden to my mother,” Walker, who lives in Columbus, said. “She has to do so much because I can do so little. There are days where I am just useless, the pain is so bad.”

Since she inherited the gene from both her parents, Walker has a textbook case of the autoimmune disease with all of its worst symptoms. The condition, which causes the immune system to mistakenly attack healthy tissue, gets progressively worse if left untreated.

Without health insurance, Walker’s only recourse is a free clinic in Tupelo, about an hour and a half away from where she lives in Columbus. The clinic is able to prescribe her thyroid medications to varying degrees of success, but it’s nothing compared to the quality of life improvement she might experience if she were able to get the proper tests done and potentially undergo a more permanent solution like thyroid surgery.

One of the 10 medications she’s currently on helps treat the insomnia associated with Graves’ disease, but it sometimes causes her to sleep through the day. None of the medications help alleviate her back pain or the gut issues, chills or tremors she lives with.

“It’s very scary to think I don’t have anybody to check me out every month … every day I’m wondering if I’ll wake up,” she mused.

As a childless adult, Walker doesn’t qualify for Medicaid – period. She says the last two times she applied for disability Medicaid, case workers told her they could only help her if she got pregnant.

“I was shocked,” Walker said. “I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. Mississippi is one of the strangest states ever. The only way to help me is if I have children?”

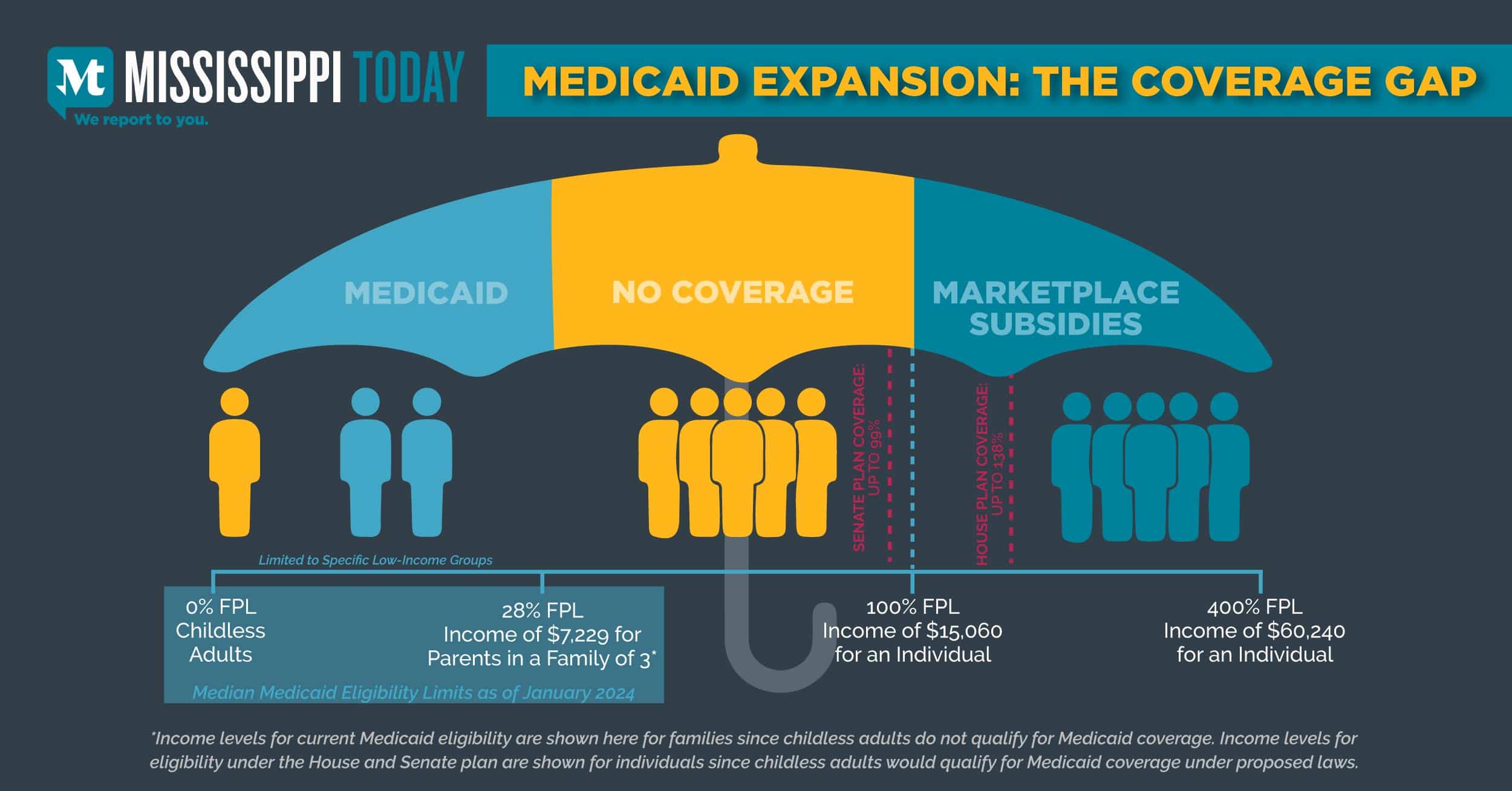

Even if she had children, or if that rule didn’t exist, Walker was at that time making more than 28% of the federal poverty level, a mere $7,000 annually for a family of three – the maximum salary a Mississippi family can make and still qualify for Medicaid – working full-time at her jobs in retail and car sales.

And she’s far from the only one. Anyone making at least minimum wage working full-time makes more than 28% of the federal poverty level, which then counts against them and disqualifies them from Medicaid.

Walker is one of tens of thousands of Mississippians who fall into the “coverage gap.” These individuals don’t qualify for Medicaid under the state’s current restrictions but make less than the 100% of the federal poverty level, about $15,000 a year for an individual, that would qualify them for subsidies that make marketplace insurance affordable.

The coverage gap exists in states that have not expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, which presumed all states would automatically expand Medicaid. However, a 2012 Supreme Court ruling made expansion optional for states.

New proposals in the Mississippi Legislature would expand Medicaid, as 40 other states have done, covering families and adults with a household income of up to 138% of the federal poverty level, under the House plan, or 99%, under the Senate plan.

Both plans would cover more Mississippians than are currently covered. But under both plans, the threat of a work requirement could leave individuals like Walker behind.

Policing and enforcing the work requirement costs more than it would cost to insure the population of unemployed people who would become eligible for Medicaid under expansion. Experts say developing new administrative systems would burden an already precarious system and could cost up to tens of millions of dollars. What’s more is the paperwork can be confusing to enrollees, causing legitimately employed and income-eligible individuals to be denied coverage.

The House plan would expand Medicaid regardless of whether the federal government approved a special waiver necessary to implement a work requirement. But the Senate plan is entirely contingent on the approval of the work requirement – unlikely to happen under the Biden administration, which has rescinded work requirements previously granted under the Trump administration and not approved new ones.

Dr. Dustin Gentry, a family physician at Winston Medical Center in Louisville, is a self-described Republican who says he can’t abide by his party’s long-standing belief that Medicaid expansion isn’t the most financially responsible decision for Mississippi.

“I want Mississippi to have coverage for uninsured patients in the coverage gap, and I want us to do it in a way that makes most sense financially, which is the House plan,” Gentry said. “It doesn’t make sense for us to not take the (federal) money, when everybody else is taking it. It puts us further behind.”

A plan like the Senate’s would leave $1 billion federal dollars on the table. An expansion plan that doesn’t cover people making up to 138% of the federal poverty level, about $20,000 annually for an individual, isn’t considered “expansion” under the Affordable Care Act, and therefore doesn’t qualify for the increased federal match rate, nor the additional two-year financial incentive the ACA gives to newly-expanded states.

Mississippians are already paying for Medicaid to cover hundreds of thousands of poor, working people – in other states.

“It’s important to note that the residents of Mississippi and the other holdout states have not been spared from paying for Medicaid expansion,” Dr. Joe Thompson, the Arkansas surgeon general under Republican Gov. Mike Huckabee and Democratic Gov. Mike Beebe told Mississippi Today. “They have been helping to fund it for over a decade through their federal tax dollars, but the money has been flowing into states like Arkansas and Louisiana instead of benefiting the working poor, hospitals, and economies of their home states.”

And hospitals are dying because uninsured individuals’ only recourse for medical care is the emergency room – the most expensive place to receive care. One report estimates that nearly half of all Mississippi’s rural hospitals are at risk of closure due to uncompensated care costs hospitals must front to cover these individuals each year.

“Everybody’s got heartburn over people ‘getting something they don’t deserve,’” Gentry said. “But these people get free care anyways. They’re getting it from the emergency room, and it’s uncompensated care, and it’s the most expensive way to get care possible. So they’re getting it for free, we’re just bickering over who is going to pay for it.”

And while emergency rooms cannot turn down individuals who require immediate life-saving care, they do nothing to provide the necessary preventative care to improve the quality of life for people like Walker.

Walker believes if she could get the proper tests and treatment plan, she could go back to work and live independently. But with Gov. Tate Reeves promising to veto any expansion bill and the Senate hung up on a stringer work requirement, the chances Walker will get the care she needs look slim.

The six lawmakers tasked with hammering out a conference report on Medicaid expansion currently have until April 27 to file the bill and until April 29 to adopt it.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

Derrick Simmons: Monday’s Confederate Memorial Day recognition is awful for Mississippians

Editor’s note: This essay is part of Mississippi Today Ideas, a platform for thoughtful Mississippians to share fact-based ideas about our state’s past, present and future. You can read more about the section here.

Each year, in a handful of states, public offices close, flags are lowered and official ceremonies commemorate “Confederate Memorial Day.”

Mississippi is among those handful of states that on Monday will celebrate the holiday intended to honor the soldiers who fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War.

But let me be clear: celebrating Confederate Memorial Day is not only racist but is bad policy, bad governance and a deep stain on the values we claim to uphold today.

First, there is no separating the Confederacy from the defense of slavery and white supremacy. The Confederacy was not about “states’ rights” in the abstract; it was about the right to own human beings. Confederate leaders themselves made that clear.

Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens declared in his infamous “Cornerstone Speech” that the Confederacy was founded upon “the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man.” No amount of revisionist history can erase the fact that the Confederacy’s cause was fundamentally rooted in preserving racial subjugation.

To honor that cause with a state holiday is to glorify a rebellion against the United States fought to defend the indefensible. It is an insult to every citizen who believes in equality and freedom, and it is a cruel slap in the face to Black Americans, whose ancestors endured the horrors of slavery and generations of systemic discrimination that followed.

Beyond its moral bankruptcy, Confederate Memorial Day is simply bad public policy. Holidays are public statements of our values. They are moments when a state, through official sanction, tells its citizens: “This is what we believe is worthy of honor.” Keeping Confederate Memorial Day on the calendar sends a message that a government once committed to denying basic human rights should be celebrated.

That message is not just outdated — it is dangerous. It nurtures the roots of racism, fuels division and legitimizes extremist ideologies that threaten our democracy today.

Moreover, there are real economic and administrative costs to shutting down government offices for this purpose. In a time when states face budget constraints, workforce shortages and urgent civic challenges, it is absurd to prioritize paid time off to commemorate a failed and racist insurrection. Our taxpayer dollars should be used to advance justice, education, infrastructure and economic development — not to prop up a lost cause of hate.

If we truly believe in moving forward together as one people, we must stop clinging to symbols that represent treason, brutality and white supremacy. There is a legislative record that supports this move in a veto-proof majority changing the state Confederate flag in 2020. Taking Confederate Memorial Day off our official state holiday calendar is another necessary step toward a more inclusive and just society.

Mississippi had the largest population of enslaved individuals in 1865 and today has the highest percentage of Black residents in the United States. We should not honor the Confederacy or Confederate Memorial Day. We should replace it.

Replacing a racist holiday with one that celebrates emancipation underscores the state’s rich African American history and promotes a more inclusive understanding of its past. It would also align the state’s observances with national efforts to commemorate the end of slavery and the ongoing pursuit of equality.

I will continue my legislative efforts to replace Confederate Memorial Day as a state holiday with Juneteenth, which commemorates the freedom for America’s enslaved people.

It’s time to end Confederate Memorial Day once and for all.

Derrick T. Simmons, D-Greensville, serves as the minority leader in the state Senate. He represents Bolivar, Coahoma and Washington counties in the Mississippi Senate.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Derrick Simmons: Monday's Confederate Memorial Day recognition is awful for Mississippians appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Left-Leaning

This article argues against the celebration of Confederate Memorial Day, stating it glorifies a racist and failed rebellion that is harmful to societal values. It critiques the holiday as a symbol of white supremacy and advocates for replacing it with Juneteenth to honor emancipation. The language used, such as referring to the Confederate cause as “moral bankruptcy,” and the call to replace the holiday reflects a progressive stance on social justice and racial equality, common in left-leaning perspectives. Additionally, the writer urges action for inclusivity and justice, positioning the argument within modern liberal values.

Mississippi Today

On this day in 1903, W.E.B. Du Bois urged active resistance to racist policies

April 27, 1903

W.E.B. Du Bois, in his book, “The Souls of Black Folk,” called for active resistance to racist policies: “We have no right to sit silently by while the inevitable seeds are sown for a harvest of disaster to our children, black and white.”

He described the tension between being Black and being an American: “One ever feels his twoness, — an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

He criticized Washington’s “Atlanta Compromise” speech. Six years later, Du Bois helped found the NAACP and became the editor of its monthly magazine, The Crisis. He waged protests against the racist silent film “The Birth of a Nation” and against lynchings of Black Americans, detailing the 2,732 lynchings between 1884 and 1914.

In 1921, he decried Harvard University’s decisions to ban Black students from the dormitories as an attempt to renew “the Anglo-Saxon cult, the worship of the Nordic totem, the disenfranchisement of Negro, Jew, Irishman, Italian, Hungarian, Asiatic and South Sea Islander — the world rule of Nordic white through brute force.”

In 1929, he debated Lothrop Stoddard, a proponent of scientific racism, who also happened to belong to the Ku Klux Klan. The Chicago Defender’s front page headline read, “5,000 Cheer W.E.B. DuBois, Laugh at Lothrup Stoddard.”

In 1949, the FBI began to investigate Du Bois as a “suspected Communist,” and he was indicted on trumped-up charges that he had acted as an agent of a foreign state and had failed to register. The government dropped the case after Albert Einstein volunteered to testify as a character witness.

Despite the lack of conviction, the government confiscated his passport for eight years. In 1960, he recovered his passport and traveled to the newly created Republic of Ghana. Three years later, the U.S. government refused to renew his passport, so Du Bois became a citizen of Ghana. He died on Aug. 27, 1963, the eve of the March on Washington.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Jim Hood’s opinion provides a roadmap if lawmakers do the unthinkable and can’t pass a budget

On June 30, 2009, Sam Cameron, the then-executive director of the Mississippi Hospital Association, held a news conference in the Capitol rotunda to publicly take his whipping and accept his defeat.

Cameron urged House Democrats, who had sided with the Hospital Association, to accept the demands of Republican Gov. Haley Barbour to place an additional $90 million tax on the state’s hospitals to help fund Medicaid and prevent the very real possibility of the program and indeed much of state government being shut down when the new budget year began in a few hours. The impasse over Medicaid and the hospital tax had stopped all budget negotiations.

Barbour watched from a floor above as Cameron publicly admitted defeat. Cameron’s decision to swallow his pride was based on a simple equation. He told news reporters, scores of lobbyists and health care advocates who had set up camp in the Capitol as midnight on July 1 approached that, while he believed the tax would hurt Mississippi hospitals, not having a Medicaid budget would be much more harmful.

Just as in 2009, the Legislature ended the 2025 regular session earlier this month without a budget agreement and will have to come back in special session to adopt a budget before the new fiscal year begins on July 1. It is unlikely that the current budget rift between the House and Senate will be as dramatic as the 2009 standoff when it appeared only hours before the July 1 deadline that there would be no budget. But who knows what will result from the current standoff? After all, the current standoff in many ways seems to be more about political egos than policy differences on the budget.

The fight centers around multiple factors, including:

- Whether legislation will be passed to allow sports betting outside of casinos.

- Whether the Senate will agree to a massive projects bill to fund local projects throughout the state.

- Whether leaders will overcome hard feelings between the two chambers caused by the House’s hasty final passage of a Senate tax cut bill filled with typos that altered the intent of the bill without giving the Senate an opportunity to fix the mistakes.

- Whether members would work on a weekend at the end of the session. The Senate wanted to, the House did not.

It is difficult to think any of those issues will rise to the ultimate level of preventing the final passage of a budget when push comes to shove.

But who knows? What we do know is that the impasse in 2009 created a guideline of what could happen if a budget is not passed.

It is likely that parts, though not all, of state government will shut down if the Legislature does the unthinkable and does not pass a budget for the new fiscal year beginning July 1.

An official opinion of the office of Attorney General Jim Hood issued in 2009 said if there is no budget passed by the Legislature, those services mandated in the Mississippi Constitution, such as a public education system, will continue.

According to the Hood opinion, other entities, such as the state’s debt, and court and federal mandates, also would be funded. But it is likely that there will not be funds for Medicaid and many other programs, such as transportation and aspects of public safety that are not specifically listed in the Mississippi Constitution.

The Hood opinion reasoned that the Mississippi Constitution is the ultimate law of the state and must be adhered to even in the absence of legislative action. Other states have reached similar conclusions when their legislatures have failed to act, the AG’s opinion said.

As is often pointed out, the opinion of the attorney general does not carry the weight of law. It serves only as a guideline, though Gov. Tate Reeves has relied on the 2009 opinion even though it was written by the staff of Hood, who was Reeves’ opponent in the contentious 2019 gubernatorial campaign.

But if the unthinkable ever occurs and the Legislature goes too far into a new fiscal year without adopting a budget, it most likely will be the courts — moreso than an AG’s opinion — that ultimately determine if and how state government operates.

In 2009 Sam Cameron did not want to see what would happen if a budget was not adopted. It also is likely that current political leaders do not want to see the results of not having a budget passed before July 1 of this year.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

-

SuperTalk FM6 days ago

SuperTalk FM6 days agoNew Amazon dock operations facility to bring 1,000 jobs to Marshall County

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed2 days ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed2 days agoMissouri lawmakers on the cusp of legalizing housing discrimination

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days agoPrayer Vigil Held for Ronald Dumas Jr., Family Continues to Pray for His Return | April 21, 2025 | N

-

Mississippi Today7 days ago

Mississippi Today7 days ago‘Trainwreck on the horizon’: The costly pains of Mississippi’s small water and sewer systems

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days agoTrump touts manufacturing while undercutting state efforts to help factories

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Texas News Feed7 days agoMeteorologist Chita Craft is tracking a Severe Thunderstorm Warning that's in effect now

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Virginia News Feed7 days agoTaking video of military bases using drones could be outlawed | Virginia

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days agoFederal report due on Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina’s path to recognition as a tribal nation