News from the South - Alabama News Feed

Race and place can contribute to shorter lives, research suggests • Alabama Reflector

Race and place can contribute to shorter lives, research suggests

by Tim Henderson, Alabama Reflector

January 30, 2025

This story originally appeared on Stateline.

There’s growing evidence that some American demographic groups need more help than others to live longer, healthier lives.

American Indians in Western and Midwestern states have the shortest life expectancy as of 2021, 63.6 years. That’s more than 20 years shorter than Asian Americans nationwide, who can expect to live to 84, according to a recent study by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington.

White residents live shorter lives in Appalachia and some Southern states, as do Black residents in highly segregated cities and in the rural South, the study found.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

The data illustrates how Americans’ life expectancy differs based not only on race, but also on geography.

“Not everybody in this country is doing exactly the same even within a racial group, because it also depends on where they live,” said Dr. Ali Mokdad, an author of the study and the chief strategy officer for population health at the University of Washington.

“Eliminating these disparities will require investing in equitable health care, education, and employment, and confronting factors that fuel inequalities, such as systemic racism,” the report, which was published in November, concluded.

Yet the United States is seeing a surge of action this month to pull back on public awareness and stem investments in those areas.

In President Donald Trump’s first two weeks, he has stripped race and ethnicity health information from public websites, blocked public communication by federal health agencies, paused federal research and grant expenditures, and ordered a ban on diversity, equity and inclusion programs across the board, all of which can draw attention — and funding — to the needs of specific demographic groups.

The administration has removed information about clinical trial diversity from a U.S. Food and Drug Administration website, and has paused health agencies’ communications with the public and with medical providers, including advisories on communicable diseases, such as the flu, that disproportionately affect underserved communities.

The new administration’s policies are headed the wrong way, said Dr. Donald Warne, a physician and co-director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Indigenous Health. “With the stroke of a pen, they’re gonna make it worse.”

One of Trump’s actions on his first day in office was to dismantle equity programs, including reversing a 2021 Biden executive order promoting more federal support for Indigenous education, including tribal colleges and universities.

The problems Indigenous people face are inextricably linked to “toxic stress” and “just pure racism,” Warne said. “Less access to healthy foods, just chronic stress from racism and marginalization, historical trauma — all of these things lead to poor health outcomes.”

The South Dakota county where Warne grew up as a member of the Oglala Lakota tribe (the county is named after the tribe) has one of the lowest life expectancies in the country, 60.1 years as of 2024, according to localized estimates from County Health Rankings & Roadmaps, an initiative of the University of Wisconsin’s Population Health Institute.

’10 Americas’

The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation study parceled the country into what it called “10 Americas,” each with different 2021 life expectancies.

Black Americans were represented by three groups; those in the rural and low-income South had the worst life expectancies (68 years) compared with those living in highly segregated cities (71.5) and other areas (72.3).

Racism is still a major contributor to inequitable health outcomes, and without naming it and addressing it, it will make it more difficult to uproot it.

– Dr. Mary Fleming, director of Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health’s Leadership Development to Advance Equity in Health Care

Asian Americans nationwide have the longest life expectancy at 84, yet can also suffer from stereotypes and locality based problems that prevent them from getting the best care, said Lan Ðoàn, an assistant professor in the Department of Public Health Section for Health Equity at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine.

Considering Asian Americans as a single entity masks health differences, such as the high incidence of heart disease among South Asians and Filipino Americans, she said, and discourages the necessary study of individual groups.

“It perpetuates the ‘model minority’ myth where Asian people are healthier, wealthier and more successful than other racial groups,” Ðoàn said.

That’s another reason for alarm over the new administration’s attitude about health equity, said Dr. Mary Fleming, an OB-GYN and director of Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health’s Leadership Development to Advance Equity in Health Care program.

“With DEI (diversity, equity and inclusion programs) under attack, it hinders our ability to name a thing, a thing,” Fleming said. “Racism is still a major contributor to inequitable health outcomes, and without naming it and addressing it, it will make it more difficult to uproot it.”

Among white people and Hispanics, lifespans differ by region, according to the “10 Americas” in the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation study. Latinos live shorter lives in the Southwest (76) than elsewhere (79.4), and white people live longer (77.2) if they’re not in Appalachia or the lower Mississippi Valley (71.1), or in rural areas and low-income Northern states (76.7).

!function(){“use strict”;window.addEventListener(“message”,(function(a){if(void 0!==a.data[“datawrapper-height”]){var e=document.querySelectorAll(“iframe”);for(var t in a.data[“datawrapper-height”])for(var r=0;r An earlier Stateline story reported that policy, poverty, rural isolation and bad habits are shortening lives in West Virginia compared with New York. Even though the states had very similar life expectancies in 1990, West Virginia is projected to be at the bottom of the rankings by 2050, while New York is projected to be at the top. More research at a very local level is needed to find the policies and practices needed to start bridging longevity gaps, said Mokdad, the study author. Since poverty seems to dictate so much of life expectancy, it’s fruitful to look at places where lifespans have grown in recent decades despite high poverty, Mokdad said. For example, lifespans have increased in the Bronx, New York, and Monongalia County, West Virginia, despite high poverty. By contrast, they have dipped in relatively high-income areas such as Clark County, Indiana, and Henry County, Georgia. Clark County, on the Kentucky border, has a mix of urban and rural health issues that belie the relatively high income of some residents near Louisville, said Dr. Eric Yazel, health officer for the county and an emergency care physician. Part of the county is also very rural, in a part of Indiana where there was an HIV outbreak among intravenous drug users in 2014. “In a single county we see public health issues that are both rural and urban,” Yazel said. “As with a lot of areas along the Ohio River Valley, we were hit hard by the opioid epidemic and now have seen a resurgence of methamphetamine, which likely contributed to the [life expectancy] decreases.” Nationally, a spike in overdoses has begun to ease in recent years, but only among white people. Overdose death rates among Black and Native people have grown. Indigenous people also were the hardest hit during the COVID-19 pandemic, with expected lifespans dropping almost seven years between 2019 and 2021. Calvin Gorman, 50, said several friends his age in Arizona’s Navajo Nation died needlessly in the pandemic. He blames it on alcohol and pandemic isolation. “They said to just stay inside. Just stay inside. Some of them took some bottles into the house and they never came out again. I heard they died in there,” said Gorman, who commutes on foot and by hitchhiking from his home in Fort Defiance, Arizona, to a job at a gas station in Gallup, New Mexico. Warne, the Oglala Lakota physician from South Dakota, said alcohol and substance use may have been one factor in Native deaths during the pandemic, as people “self-medicated” to deal with stress. But overall, he said, the main drivers of early deaths in Native communities are high rates of infant mortality, road accidents and suicides. Warne now lives and practices medicine in North Dakota. “There’s a huge challenge for people who grow up in these settings, but many of us do move forward,” Warne said. “A lot of us wind up working in other places instead of in our home, because there just aren’t the opportunities. We should be looking at economic development as a public health intervention.” Stateline is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Stateline maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Scott S. Greenberger for questions: info@stateline.org. YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE. Alabama Reflector is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Alabama Reflector maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Brian Lyman for questions: info@alabamareflector.com. The post Race and place can contribute to shorter lives, research suggests • Alabama Reflector appeared first on alabamareflector.comHyperlocal health problems

News from the South - Alabama News Feed

‘A dream come true’: Mobile native Shemar James returns home to play in Senior Bowl

SUMMARY: Shemar James, a former standout at Faith Academy and top linebacker at Florida, is back in his hometown for the Senior Bowl. Reflecting on his journey, James shared his excitement about returning home, seeing family, and visiting his alma mater. He discussed his experience at Florida, overcoming adversity, and finishing strong in his college career. James expressed gratitude for the opportunity to play in the Senior Bowl and emphasized his continuous work to reach the next level. He also highlighted the positive feedback from coaches, showcasing his skills as a versatile linebacker capable of playing in various situations.

Mobile native and former Florida linebacker Shemar James is back in his hometown this week to compete in the Senior Bowl.

News from the South - Alabama News Feed

UAB students, UA professors file for a stay of Alabama’s anti-DEI law • Alabama Reflector

UAB students, UA professors file for a stay of Alabama’s anti-DEI law

by Alander Rocha, Alabama Reflector

January 30, 2025

Professors, students and civil rights advocates filed a motion Thursday seeking a preliminary injunction against Alabama’s SB 129, a law they claim imposes restrictions on discussions of race and gender in public universities.

The lawsuit was filed on Jan. 14 and brought by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Alabama, the Legal Defense Fund (LDF) and the Alabama State Conference of the NAACP on behalf of three University of Alabama professors and three University of Alabama in Birmingham students. It argues that the law violates the First and Fourteenth Amendments by restricting academic freedom and imposing vague prohibitions that chill free speech.

“This law undermines the fundamental mission of higher education and erodes students’ right to learn in an environment that fosters open dialogue,” said Antonio Ingram, senior counsel for LDF, in a statement. “SB 129 is at odds with the Constitution’s protections of free speech and due process.”

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

The state had not filed a response as of early Thursday afternoon. A message was left with the Ivey’s office and the University of Alabama Board of Trustees.

The legislation, which took effect on Oct. 1, 2024, bans diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs at public colleges and universities. It also prohibits teaching or advocating for what lawmakers deem “divisive concepts” related to race, sex, and systemic discrimination.

The lawsuit claims that educators fear discipline or termination if they discuss topics that could be construed as advocating for banned concepts. Students, meanwhile, have seen funding cut for organizations that support Black and LGBTQIA communities.

Plaintiffs argue that SB 129 is overly broad and ambiguous, making it unclear what discussions are allowed. The law includes exemptions for “objective” teaching of history, but provides no definition of what constitutes objectivity, leading to self-censorship among faculty.

University of Alabama professor Cassandra Simon, who teaches a course on anti-oppression and social justice, said she has already faced threats of discipline for class discussions that included systemic inequality.

Students have also been directly impacted. The lawsuit notes that the Black Student Union and Safe Zone Resource Center, which provided support for LGBTQIA students, lost access to campus spaces and funding. Student leaders say the law has led to the dismantling of spaces intended to foster inclusion and support for marginalized communities.

Alabama officials have defended the law, saying it ensures that taxpayer-funded institutions remain politically neutral and do not endorse controversial ideologies. Gov. Kay Ivey’s office has not yet commented on the injunction request.

The lawsuit draws parallels to legal challenges in Florida, where courts blocked enforcement of similar legislation under the state’s Stop W.O.K.E. Act. Plaintiffs argue that Alabama’s SB 129 imposes similar unconstitutional restrictions on academic speech and student organizations.

“Justice demands urgency,” Alison Mollman, ACLU of Alabama legal director, said in a statement. “Students and professors in our state have dealt with this unconstitutional law for several months and deserve to learn in a classroom that is free of censorship and racial discrimination.”

The court had not scheduled a hearing on the motion for a preliminary injunction as of early Thursday afternoon.

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

Alabama Reflector is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Alabama Reflector maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Brian Lyman for questions: info@alabamareflector.com.

The post UAB students, UA professors file for a stay of Alabama’s anti-DEI law • Alabama Reflector appeared first on alabamareflector.com

News from the South - Alabama News Feed

New Florida law allowing C-sections outside hospitals could be national model • Alabama Reflector

New Florida law allowing C-sections outside hospitals could be national model

by Anna Claire Vollers, Alabama Reflector

January 29, 2025

This story originally appeared on Stateline.

A recently enacted Florida law that allows doctors to deliver babies via cesarean section in clinics outside of hospitals could be a blueprint for other states, even as critics point to the role that a private equity-backed physicians group played in its passage.

The United States has poor maternal health outcomes compared with peer nations, and hospital labor and delivery units are shuttering around the country because of financial strain. Supporters say the Florida law could increase access to maternity care and lower costs for expecting patients.

But critics, including some physician, hospital and midwife groups, warn it’s an untested model that could put the health of mothers and babies at risk. They also note that private equity firms that have made other forays into health care have attracted state scrutiny for allegedly valuing profits over patient safety.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.

Alex Borsa, a researcher at Columbia University whose published work focuses on private equity’s impact on health care, said he’s not surprised that Florida has become the testing ground for such clinics.

“In addition to Florida being the Wild West in a number of policy directions, it has one of the highest concentrations of private equity-backed health care operators, including OB-GYN and fertility,” Borsa said.

Traditional birth centers are typically staffed by midwives who provide maternity care for low-risk pregnancies and births. Twenty-nine such centers operate in Florida, and about 400 are licensed around the country. The focus in these centers is on natural childbirth in a homelike setting, where women labor without anesthesia and deliver babies vaginally.

Florida’s law creates a new designation, called an “advanced birth center,” that allows physicians to offer labor and delivery services at a freestanding clinic, including delivery by cesarean section. There currently are no such centers. A C-section is a surgical procedure performed with anesthesia in which a baby is delivered through an incision in the patient’s abdomen and uterus. C-sections are generally reserved for situations in which a doctor believes a vaginal birth could be risky for the mother or baby.

We’re primarily opposed to it because you’re calling a lion a tiger.

– Kate Bauer, executive director of the American Association of Birth Centers

Prior to the law’s passage last spring, C-sections could only be performed in hospitals, which have the staffing and equipment designed for surgery and potential complications.

But a private equity-owned physician group called Women’s Care Enterprises in recent years lobbied Florida legislators for the new designation. The group, owned by London-based investment firm BC Partners, operates about 100 clinics across Florida and a dozen more in Arizona, California and Kentucky.

The new designation was tucked inside a larger health policy bill and became law despite opposition from medical and midwifery groups.

“Both mom and baby deserve access to the best possible care, which is why we believe that C-sections should be performed exclusively in the hospital setting where doctors, multidisciplinary teams, sophisticated equipment, and other critical resources are immediately available in the event complications arise,” Florida Hospital Association President and CEO Mary Mayhew told Stateline in a statement.

But the association didn’t fight the bill, which among other things increased Medicaid payments to hospitals for maternity care. Other groups did oppose it.

“We’re primarily opposed to it because you’re calling a lion a tiger,” said Kate Bauer, executive director of the American Association of Birth Centers, a nonprofit that sets national standards for birth centers.

She noted that while advanced birth centers would offer maternity care outside a hospital setting, they are not the same as traditional midwifery-based birth centers. Midwife-attended births are for people with low-risk pregnancies and tend to focus on low-intervention care and emphasize natural birthing techniques. Physician-attended births tend to rely on more advanced medical interventions, like epidurals and labor-inducing medication.

Private equity jumps in

Florida lawmakers supporting the new advanced birth center designation have said it has the potential to increase access to maternity care in underserved areas and reduce costs. Just two of Florida’s 22 rural hospitals have labor and delivery services.

The staff of Florida state Sen. Gayle Harrell, the Republican who sponsored the bill, told Stateline she was unavailable to comment on it. But in previous committee hearings, Republican legislators heralded the centers as an innovative solution for obstetrical care.

“I think what we are hearing from our medical community is the desire for options,” state Sen. Colleen Burton, a Republican, said at a December 2023 committee hearing on the bill. “And what we’re particularly hearing from are patients, from Floridians, [who want] options. And potentially this could provide a lower-cost option.”

But critics question whether OB-GYNs, already in short supply in Florida, are likely to open advanced birth centers in low-income and rural communities where a larger share of patients have Medicaid. The government-sponsored insurance reimburses doctors significantly less for maternity care compared with private insurance.

Borsa, of Columbia University, co-authored a 2020 study that found private equity-owned OB-GYN offices were more likely to be located in urban areas with median household incomes above the national average.

Private equity firms use pooled money from investors to buy controlling stakes in companies. They typically focus on boosting the value of a company before selling it within a few years, ideally at a profit. In the past decade, private equity investors have spent $1 trillion acquiring health care companies.

Borsa said he and his colleagues have found strong evidence that private equity involvement in health care “pretty consistently increases costs to patients and payers.”

“There’s a fantasy that Wall Street investors are somehow going to increase access in some of the most rural and poor parts of the country, but we haven’t seen evidence of that,” he said.

In recent years, private equity’s involvement in the health care industry has drawn public ire and legislative scrutiny. Earlier this month, for example, the U.S. Senate Budget Committee released a report detailing how private equity firms wrung hundreds of millions from struggling hospitals.

Dr. Helen Kuroki, the chief medical officer for Women’s Care Enterprises, declined to comment on its support of the new law and on when it might open an advanced birth center. Representatives have previously said they’re looking at opening a center in Tampa or Orlando.

Labor and delivery services tend to be financial losers for hospitals, thanks to low reimbursement rates, particularly from Medicaid. In rural areas, where Medicaid covers as many as half of all births, reimbursement doesn’t cover the full cost of providing obstetrical services.

If patients covered by better-paying private insurance flock to freestanding birth centers that can perform C-sections, that would leave hospitals with a higher proportion of Medicaid patients. And owning the surgical space would allow physicians groups such as Women’s Care Enterprises to keep more of the reimbursement dollars that would normally go to a hospital.

Like surgical centers — sort of

Supporters have compared Florida’s new birth center model to outpatient surgery centers, where patients undergo surgical procedures that don’t require overnight hospital stays. Patients who undergo C-sections would be able to stay overnight at the new birth centers.

But critics argue a C-section is inherently different from, say, cataract surgery or a tonsillectomy.

“We’ve seen outpatient surgery centers can be a successful health care delivery model,” said Bauer, of the birth centers association. “For me, the primary difference is that surgical birth is the only surgery where, when you’re done, you have an extra person. And it’s an extra person whose health may be compromised.”

Some Florida lawmakers expressed concern that the new centers wouldn’t be required to have pediatric specialists on hand to care for a baby if there’s a problem after the birth. The centers are required to have a written agreement with a local hospital for transferring patients with complications. And they also must follow most safety standards for outpatient surgical centers.

So far, Florida remains an outlier. Legislators in other states have yet to introduce similar bills.

But as private equity firms deepen their involvement in women’s health and other health care sectors, Borsa expects them to ratchet up their lobbying of state legislators to win favorable policy changes.

“We could see more health care lobbying, and specifically around this issue in other parts of the country,” he said. “I don’t think this is a one-off, especially if they find they can derive profits.”

Stateline is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Stateline maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Scott S. Greenberger for questions: info@stateline.org.

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.

Alabama Reflector is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Alabama Reflector maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Brian Lyman for questions: info@alabamareflector.com.

The post New Florida law allowing C-sections outside hospitals could be national model • Alabama Reflector appeared first on alabamareflector.com

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed7 days agoTrump International Airport proposed, renaming Dulles | North Carolina

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed7 days agoTrump’s new Justice Department leadership orders a freeze on civil rights cases

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed7 days agoThawing out from the deep freeze this weekend

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed3 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed3 days agoTrump’s federal funding freeze leads to confusion, concern among Alabama agencies, nonprofits • Alabama Reflector

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days agoDemocrats and voting groups say a bid to toss out North Carolina ballots is an attack on democracy

-

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed7 days agoCauseway reopens to drivers in Louisiana

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed7 days agoTrump threatens to abolish FEMA in return to Helene-battered western North Carolina • Asheville Watchdog

-

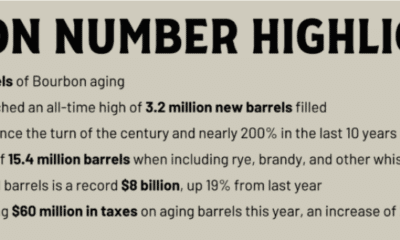

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed4 days agoKentucky’s bourbon industry worries as potential 50% EU-imposed tariffs loom