z_wei/iStock / Getty Images Plus

Jaime L Kucinskas, Hamilton College

On the eve of Donald Trump’s inauguration as the 47th president of the United States, some people who work for the federal government are concerned.

Trump and his allies have repeatedly promised to dismantle the administrative state and fire those they perceive as disloyal. Trump’s former – and likely future – director of the Office of Management and Budget, Russell Vought, for example, has threatened to “put bureaucrats in trauma.” That includes the possibility of weakening rules meant to protect public servants from political interference.

Amid these threats and loyalty tests used to vet potential appointees, many career civil servants fear that they may end up in ethical binds, caught between the instructions of their bosses and their duty to serve the American people.

During the first Trump presidency, I spoke with 66 career civil servants working across agencies, including in some of the most contested parts of the government. I tracked their experiences and challenges over the course of the administration from 2017 until 2020, doing 116 interviews in all. These form the basis for my forthcoming book, “The Loyalty Trap.” This work identified some of the ways longtime government workers managed to stay sane, keep their jobs and continue to serve the American people.

Maintaining quality work

As happened during Trump’s first term, government employees are being advised by experienced colleagues to “stay calm and keep their head down,” as The Washington Post reported. Some are already trying to protect potentially politicized work. For instance, they are trying to revise job titles that use terms such as diversity or climate. They aim to use words less likely to be targeted by the incoming administration, referring more obliquely to climate change and civil and human rights protections.

erhui1979/DigitalVision Vectors via Getty Images

This pressure is real: During Trump’s first presidency, a number of federal civil servants I talked to described their mental health declining, and declining morale, productivity and innovation at work.

Among a sizable proportion of the people I spoke with, the pressures at work became too much; about a quarter of those I spoke with quit during the first Trump administration.

Those who stayed faced Trump appointees’ suspicion, threats of political retribution and sidelining of expert guidance. Many reported feeling quite alone. Nearly all sought to remain loyal to serving the presidential administration. But in the face of leadership’s threats and conflicting advice, some of which they said they believed could be potentially illegal, and without clear guidance from above, some workers became unable to do their jobs.

As one middle-aged midlevel manager told me when a senior employee in his agency was removed from her position after some Trump allies publicly criticized work in the agency, “They found someone to punish. And that obviously had a very chilling effect on everyone.” The manager said it’s “terrifying” to see people who may have lost their jobs simply because they did those jobs properly.

Under these conditions, he said, helping appointees sometimes meant “just doing little, quite frankly … just doing what’s necessary, and it means waiting to help educate folks about what their options are as we go forward, as opposed to getting too fired up about things. Because it’s safer.”

He also noted the binds midlevel employees faced as appointees fought over policy agendas levels above them. The appointees, he said, “want things which are in direct contradiction of each other … and so I don’t know what’s going on. I don’t know what all this stuff means.”

Being stuck in such chaotic situations made this employee feel trapped between choosing to be “a slick salesman and come out of it looking good,” but then facing “unintended consequences down the line.” Or, “You could also be not a slick salesman, have trouble now, but maybe no unintended consequences down the line. So take your pick, and neither of them sound very great.”

Some career civil servants avoided sharing their woes and challenges with each other, not wanting to burden others facing difficult situations as well or fail to uphold their own professional standards. As one lawyer working in international affairs told me, “There’s no point in really commiserating – everybody has their particular burden to carry – and a lot more just frustration that normal processes just aren’t working.”

Yet, even among those who felt most alone, I found they had many experiences in common with others who also felt isolated in trying to walk a precarious moral and ethical tightrope between their desire to faithfully serve the elected president – under chaotic leadership and insufficient and sometimes questionably legal guidance – and do quality work upholding the law and benefiting the nation and the American public.

VectorMine/iStock/Getty Images Plus

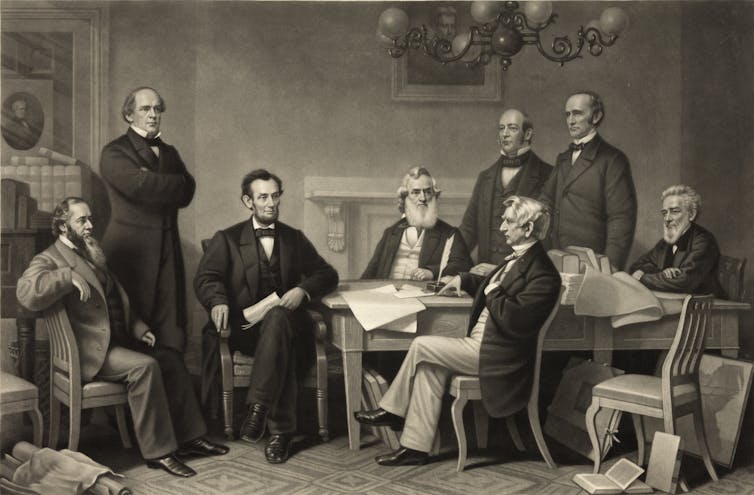

Keeping government functioning

Some civil servants said they tried to keep their departments running smoothly by doing their work as they had been doing before the Trump administration. In light of conflicts between appointees, Trump family members, the president and other Trump allies with unspecified roles, some waited to receive formal orders from authorized supervisors. Fearing retribution, they waited rather than anticipating guidance – as they might have done under leaders with more clear directives who fostered more workplace trust, communication and adhered to organizational structures.

Civil servants also emphasized the importance of documenting illegal behavior and other gross ethical transgressions witnessed at work, even if they chose not to share their records at the time. When they felt that they were in more psychologically safe working conditions under different leadership, or that they could help hold others accountable for illegal or inappropriate behavior, some reported them to official channels such as their department’s inspector general’s office or to congressional oversight committee staff.

Some of those in the most politicized parts of the government emphasized trying to maintain islands of functioning even in seas of disarray. One senior leader spoke of trying to maintain the “overall footprint of the program” and “strong staff,” even as he adhered to instructions from the administration to reduce the scale of their work.

Those who seemed to manage the best, in the most chaotic and politicized locations in the government, reported having strong interpersonal connections within their units, as well as outside the government. They reported being able to maintain their moral and ethical integrity at work thanks to support from supervisors, mentors and colleagues with shared commitments to the public, democracy, agency missions, the law and the Constitution. Some reported the importance of maintaining their personal moral compass by doing local volunteer work, through support from their families and friends, and participation in religious organizations.

When their values and commitments contrasted with the first Trump administration’s agenda, some civil servants reported trying to speak up to superiors and elicit more feedback before decisions were made. A few reported slow-walking work they thought was harmful to the public or to the nation’s best interests. In general, though, after appointees made decisions, civil servants said they did their best to respect and support them and the elected president.![]()

Jaime L Kucinskas, Associate Professor of Sociology, Hamilton College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.