Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images

Philip Klinkner, Hamilton College

Think Donald Trump can’t be president after his second term is up in January 2029? Think again.

When President-elect Donald Trump met with congressional Republicans shortly after his November 2024 election victory, he floated the idea of another term: “I suspect I won’t be running again unless you say, ‘He’s so good we’ve got to figure something else out.’”

At first glance, this seems like an obvious joke. The 22nd Amendment to the Constitution is clear that Trump can’t be elected again. The text of the amendment states:

“No person shall be elected to the office of the President more than twice, and no person who has held the office of President, or acted as President, for more than two years of a term to which some other person was elected President shall be elected to the office of the President more than once.”

That amendment was passed in response to Franklin Roosevelt’s four elections to the presidency. Since George Washington had stepped down at the end of his second term, no president had sought a third term, much less a fourth. The amendment was clearly meant to prevent presidents from serving more than two terms in office.

Abbie Rowe, National Archives and Records Administration. Office of Presidential Libraries. Harry S. Truman Library, via Wikimedia Commons

Because Trump has been elected president twice already, the plain language of the amendment bars him from being elected a third time. Some have argued that since Trump’s terms were nonconsecutive, the amendment doesn’t apply to him. But the amendment makes no distinction between consecutive and nonconsecutive terms in office.

Though the 22nd Amendment prohibits Trump from being elected president again, it does not prohibit him from serving as president beyond Jan. 20, 2029. The reason for this is that the 22nd Amendment only prohibits someone from being “elected” more than twice. It says nothing about someone becoming president in some other way than being elected to the office.

Skirting the rules

There are a few potential alternate scenarios. Under normal circumstances, they would be next to impossible. But Donald Trump has never been a normal president.

On issue after issue, Trump has pushed the outer limits of presidential power. Most importantly, he has already shown his willingness to bend or even break the law to stay in office. And while Trump claims he’s only joking when he floats the idea of a third term, he has a long history of using “jokes” as a way of floating trial balloons.

Furthermore, once he leaves office, Trump could once again face the prospect of criminal prosecution and possibly jail time, further motivating him to stay in power. As Trump’s second term progresses, don’t be surprised if Americans hear more about how he might try to stay in office. Here is what the Constitution says about that prospect.

Other ways to become president

Nine people have served as president without first being elected to that office. John Tyler, Millard Fillmore, Andrew Johnson, Chester Arthur, Theodore Roosevelt, Calvin Coolidge, Harry Truman, Lyndon Johnson and Gerald Ford were all vice presidents who stepped into the office when their predecessors either died or resigned.

The 22nd Amendment does not bar a term-limited president from being elected vice president. On the other hand, the 12th Amendment does state that “no person constitutionally ineligible to the office of the President shall be eligible to that of the Vice-President of the United States.”

It’s not clear whether this restriction applies to a two-term president who is ineligible for a third term because of the 22nd Amendment – or whether it merely imposes on the vice president the Constitution’s other criteria for presidential eligibility, namely that they be a natural-born citizen of the United States, at least 35 years of age and have lived in the U.S. for at least 14 years.

That question would have to be decided by the U.S. Supreme Court. Should the justices decide in Trump’s favor – as they have recently on questions regarding the 14th Amendment’s insurrection clause and presidential immunity – then the 2024 ticket of Trump-Vance could become the 2028 Vance-Trump ticket. If elected, Vance could then resign, making Trump president again.

No resignation needed

But Vance would not even have to resign in order for a Vice President Trump to exercise the power of the presidency. The 25th Amendment to the Constitution states that if a president declares that “he is unable to discharge the powers and duties of the office … such powers and duties shall be discharged by the Vice President as Acting President.”

In fact, the U.S. has had three such acting presidents – George H.W. Bush, Dick Cheney and Kamala Harris. All of them held presidential power for a brief period when the sitting president underwent anesthesia during medical procedures; Cheney did it twice.

In this scenario, shortly after taking office on Jan. 20, 2029, President Vance could invoke the 25th Amendment by notifying the speaker of the House and the president pro tempore of the Senate that he is unable to discharge the duties of president. He would not need to give any reason or proof of this incapacity.

Vice President Trump would then become acting president and assume the powers of the presidency until such time as President Vance issued a new notification indicating that he was able to resume his duties as president.

‘Tandemocracy’

But exercising the power of the presidency doesn’t even necessarily require being president or acting president.

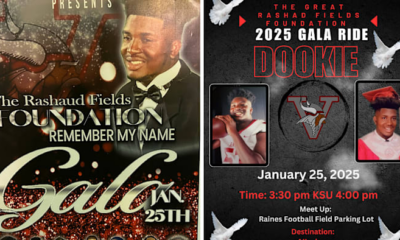

Trump has repeatedly expressed his admiration for autocratic Russian President Vladimir Putin, so he might want to follow the example of the Medvedev-Putin “tandemocracy.”

Mikhail Svetlov/Getty Images

In 2008, term limits in the Russian constitution prevented Putin from running for president after two consecutive terms. Instead, he selected a loyal subordinate, Dmitry Medvedev, to run for president.

When elected, Medvedev appointed Putin as his prime minister. By most accounts, Putin remained firmly in power and made most of the important decisions. Following this example, a future Republican president could appoint Trump to an executive branch position from which he could still exercise power.

In 2012, Putin was able to run for president again, and he and Medvedev once again swapped roles. Since then, Putin has succeeded in amending the Russian Constitution to effectively allow him to remain president for the rest of his life.

Using a figurehead

Then again, Trump might just want to avoid all of these legal subterfuges by following the example of George and Lurleen Wallace. In 1966, the Alabama Constitution prevented Wallace from running for a third consecutive term as governor. Still immensely popular and unwilling to give up power, Wallace chose to have his wife, Lurleen, run for governor. It was clear from the beginning that Lurleen was just a figurehead for George, who promised to be an adviser to his wife, at a salary of $1 a year.

The campaign’s slogan of “Two Governors, One Cause,” made it clear that a vote for Lurleen was really a vote for George.

Lurleen won in a landslide.

According to one account of her time in office, the Wallaces had “something of a Queen-Prime Minister relationship: Mrs. Wallace handles the ceremonial and formal duties of state. Mr. Wallace draws the grand outlines of state policy and sees that it is carried out.”

Trump’s wife was not born a U.S. citizen and therefore isn’t eligible to be president. But as the head of the Republican Party, Trump could ensure that the next GOP presidential candidate was a member of his family or some other person who would be absolutely loyal and obedient to him. If that person went on to win the White House in 2028, Trump could serve as an unofficial adviser, allowing him to continue to wield the power of the presidency without the actual title.![]()

Philip Klinkner, James S. Sherman Professor of Government, Hamilton College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.