Westend61/Getty Images

Mark R. O’Brian, University at Buffalo

Vaccinations provide significant protection for the public against infectious diseases and substantially reduce health care costs. Therefore, it is noteworthy that President-elect Donald Trump wants Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a leading critic of childhood vaccination, to be secretary of Health and Human Services.

Doctors, scientists and public health researchers have expressed concerns that Kennedy would turn his views into policies that could undermine public health. As a case in point, news reports have highlighted how Kennedy’s lawyer, Aaron Siri, has in recent years petitioned the Food and Drug Administration to withdraw or suspend approval of numerous vaccines over alleged safety concerns.

I am a biochemist and molecular biologist studying the roles microbes play in health and disease. I also teach medical students and am interested in how the public understands science.

Here are some facts about vaccines that Kennedy and Siri get wrong:

Vaccines are effective and safe

Public health data from 1974 to the present conclude that vaccines have saved at least 154 million lives worldwide over the past 50 years. Vaccines are also continually monitored for safety in the U.S.

Nevertheless, the false claim that vaccines cause autism persists despite study after study of large populations throughout the world showing no causal link between them.

Claims about the dangers of vaccines often come from misrepresenting scientific research papers. In an interview with podcaster Joe Rogan, Kennedy incorrectly cited studies allegedly showing vaccines cause massive brain inflammation in laboratory monkeys, and that the hepatitis B vaccine increases autism rates in children by over 1,000-fold compared with unvaccinated kids. Those studies make no such claims.

In the same interview, Kennedy also made the unusual claim that a 2002 vaccine study included a control group of children 6 months of age and younger who were fed mercury-contaminated tuna sandwiches. No sandwiches are mentioned in that study.

Similarly, Siri filed a petition in 2022 to withdraw approval of a polio vaccine based on alleged safety concerns. The vaccine in question is made from an inactivated form of the polio virus, which is safer than the previously used live attenuated vaccine. The inactivated vaccine is made from polio virus cultured in the Vero cell line, a type of cell that researchers have been safely using for various medical applications since 1962. While the petition uses provocative language comparing this cell line to cancer cells, it does not claim that it causes cancer.

Elena Zaretskaya/Moment via Getty Images

Vaccines undergo the same approval process as other drugs

Clinical trials for vaccines and other drugs are blinded, randomized and placebo-controlled studies. For a vaccine trial, this means that participants are randomly divided into one group that receives the vaccine and a second group that receives a placebo saline solution. The researchers carrying out the study, and sometimes the participants themselves, do not know who has received the vaccine or the placebo until the study has finished. This eliminates bias.

Results are published in the public domain. For example, vaccine trial data for COVID-19, human papilloma virus, rotavirus and hepatitis B are available for anyone to access.

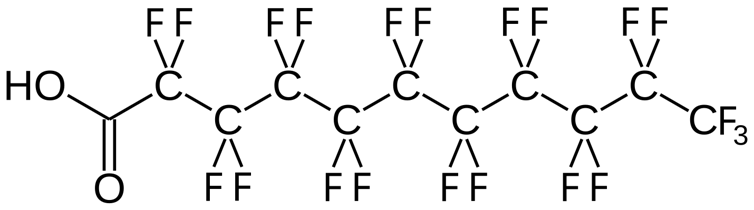

Aluminum adjuvants help boost immunity

Kennedy is co-counsel with a law firm that is suing the pharmaceutical company Merck based in part on the unfounded assertion that the aluminum in one of its vaccines causes neurological disease. Aluminum is added to many vaccines as an adjuvant to strengthen the body’s immune response to the vaccine, thereby enhancing the body’s defense against the targeted microbe.

The law firm’s claim is based on a 2020 report showing that brain tissue from some patients with Alzheimer’s disease, autism and multiple sclerosis have elevated levels of aluminum. The authors of that study do not assert that vaccines are the source of the aluminum, and vaccines are unlikely to be the culprit.

Notably, the brain samples analyzed in that study were from 47- to 105-year-old patients. Most people are exposed to aluminum primarily through their diets, and aluminum is eliminated from the body within days. Therefore, aluminum exposure from childhood vaccines is not expected to persist in those patients.

Ironically, Kennedy’s lawyer, Siri, wants the FDA to withdraw some vaccines for containing less aluminum than stated by the manufacturer.

Vaccine manufacturers are liable for injury or death

Kennedy’s lawsuit against Merck contradicts his insistence that vaccine manufacturers are fully immune from litigation.

His claim is based on an incorrect interpretation of the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program, or VICP. The VICP is a no-fault federal program created to reduce frivolous lawsuits against vaccine manufacturers, which threaten to cause vaccine shortages and a resurgence of vaccine-preventable disease.

A person claiming injury from a vaccine can petition the U.S. Court of Federal Claims through the VICP for monetary compensation. If the VICP petition is denied, the claimant can then sue the vaccine manufacturer.

Andreas Ren Photography Germany/Image Source via Getty Images

The majority of cases resolved under the VICP end in a negotiated settlement between parties without establishing that a vaccine was the cause of the claimed injury. Kennedy and his law firm have incorrectly used the payouts under the VICP to assert that vaccines are unsafe.

The VICP gets the vaccine manufacturer off the hook only if it has complied with all requirements of the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act and exercised due care. It does not protect the vaccine maker from claims of fraud or withholding information regarding the safety or efficacy of the vaccine during its development or after approval.

Good nutrition and sanitation are not substitutes for vaccination

Kennedy asserts that populations with adequate nutrition do not need vaccines to avoid infectious diseases. While it is clear that improvements in nutrition, sanitation, water treatment, food safety and public health measures have played important roles in reducing deaths and severe complications from infectious diseases, these factors do not eliminate the need for vaccines.

After World War II, the U.S. was a wealthy nation with substantial health-related infrastructure. Yet, Americans reported an average of 1 million cases per year of now-preventable infectious diseases.

Vaccines introduced or expanded in the 1950s and 1960s against diseases like diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, measles, polio, mumps, rubella and Haemophilus influenza B have resulted in the near or complete eradication of those diseases.

It’s easy to forget why many infectious diseases are rarely encountered today: The success of vaccines does not always tell its own story. RFK Jr.’s potential ascent to the role of secretary of Health and Human Services will offer up ample opportunities to retell this story and counter misinformation.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on July 26, 2024.![]()

Mark R. O’Brian, Professor and Chair of Biochemistry, University at Buffalo

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.