Marcos Fernandez Tous, University of North Dakota

Off the coast of Baja California in December 2022, sun sparkled over the rippling sea as waves sloshed around the USS Portland dock ship. Navy officials on the deck scrutinized the sky in search of a sign. The glow appeared suddenly.

A tiny spot at first, it gradually grew to a round circle falling at a great speed from the fringes of space. It was NASA’s Orion capsule, which would soon end the 25-day Artemis I mission around and beyond the Moon with a fiery splashdown into the ocean.

Orion’s reentry followed a sharply angled trajectory, during which the capsule fell at an incredible speed before deploying three red and white parachutes. As the mission finished its trip of over 270,000 miles (435,000 kilometers), it looked to those on the deck of the USS Portland like the capsule had made it home in a single piece.

As the recovery crew lifted Orion to the carrier’s deck, shock waves ruffled across the capsule’s surface. That’s when crew members started to spot big cracks on Orion’s lower surface, where the capsule’s exterior bonds to its heat shield.

But why wouldn’t a shield that has endured temperatures of about 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit (2,760 degrees Celsius) sustain damage? Seems only natural, right?

This mission, Artemis I, was uncrewed. But NASA’s ultimate objective is to send humans to the Moon in 2026. So, NASA needed to make sure that any damage to the capsule– even its heat shield, which is meant to take some damage – wouldn’t risk the lives of a future crew.

On Dec. 11, 2022 – the time of the Artemis I reentry – this shield took severe damage, which delayed the next two Artemis missions. While engineers are now working to prevent the same issues from happening again, the new launch date targets April 2026, and it is coming up fast.

As a professor of aerospace technology, I enjoy researching how objects interact with the atmosphere. Artemis I offers one particularly interesting case – and an argument for why having a functional heat shield is critical to a space exploration mission.

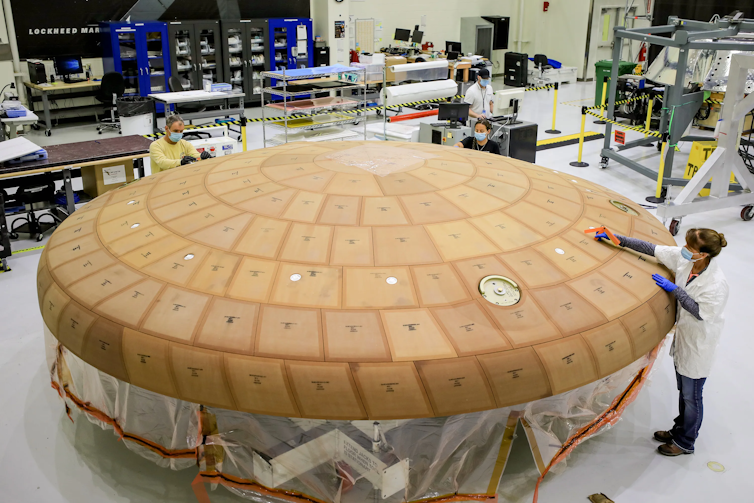

NASA via AP

Taking the heat

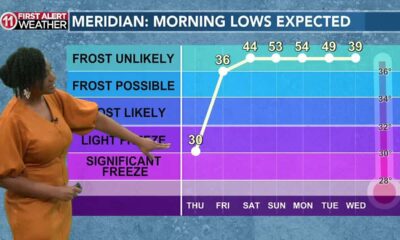

To understand what exactly happened to Orion, let’s rewind the story. As the capsule reentered Earth’s atmosphere, it started skimming its higher layers, which acts a bit like a trampoline and absorbs part of the approaching spacecraft’s kinetic energy. This maneuver was carefully designed to gradually decrease Orion’s velocity and reduce the heat stress on the inner layers of the shield.

After the first dive, Orion bounced back into space in a calculated maneuver, losing some of its energy before diving again. This second dive would take it to lower layers with denser air as it neared the ocean, decreasing its velocity even more.

While falling, the drag from the force of the air particles against the capsule helped reduced its velocity from about 27,000 miles per hour (43,000 kilometers per hour) down to about 20 mph (32 kph). But this slowdown came at a cost – the friction of the air was so great that temperatures on the bottom surface of the capsule facing the airflow reached 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit (2,760 degrees Celsius).

At these scorching temperatures, the air molecules started splitting and a hot blend of charged particles, called plasma, formed. This plasma radiated energy, which you could see as red and yellow inflamed air surrounding the front of the vehicle, wrapping around it backward in the shape of a candle.

No material on Earth can stand this hellish environment without being seriously damaged. So, the engineers behind these capsules designed a layer of material called a heat shield to be sacrificed through melting and evaporation, thus saving the compartment that would eventually house astronauts.

By protecting anyone who might one day be inside the capsule, the heat shield is a critical component.

NASA/Isaac Watson

In the form of a shell, it is this shield that encapsulates the wide end of the spacecraft, facing the incoming airflow – the hottest part of the vehicle. It is made of a material that is designed to evaporate and absorb the energy produced by the friction of the air against the vehicle.

The case of Orion

But what really happened with Orion’s heat shield during that 2022 descent?

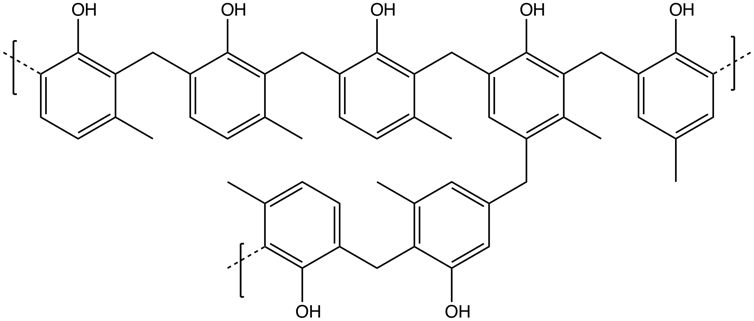

In the case of Orion, the heat shield material is a composite of a resin called Novolac – a relative to the Bakelite which some firearms are made of – absorbed in a honeycomb structure of fiberglass threads.

Smokefoot/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

As the surface is exposed to the heat and airflow, the resin melts and recedes, exposing the fiberglass. The fiberglass reacts with the surrounding hot air, producing a black structure called char. This char then acts as a second heat barrier.

NASA used the same heat shield design for Orion as the Apollo capsule. But during the Apollo missions, the char structure didn’t break like it did on Orion.

After nearly two years spent analyzing samples of the charred material, NASA concluded that the Orion project team had overestimated the heat flow as the craft skimmed the atmosphere upon reentry.

As Orion approached the upper layers of the atmosphere, the shield started melting and produced gases that may have escaped through pores in the material. Then, when the capsule gained altitude again, the outer layers of the resin froze, trapping the heat from the first dive inside. This heat vaporized the resin.

When the capsule dipped into the atmosphere the second time, the gas expanded before finding a way out as it heated again – kind of like how a frozen lake thaws upward from the bottom – and its escape produced cracks in the capsule’s surface where the char structure got damaged. These were the cracks the recovery crew saw on the capsule after it splashed down.

In a Dec. 5, 2024, press conference, NASA officials announced that the Artemis II mission will be designed with a modified reentry trajectory to prevent heat from accumulating.

For Artemis III, which is planned to launch in 2027, NASA intends to use new manufacturing methods for the shield, making it more permeable. The outside of the capsule will still get very hot during reentry, and the heat shield will still evaporate. But these new methods will help keep the astronauts cozy in the capsule all the way through splashdown.

Chonglin Zhang, assistant professor of mechanical engineering at the University of North Dakota, assisted in researching this article.![]()

Marcos Fernandez Tous, Assistant Professor of Space Studies, University of North Dakota

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.