Microfluidics makes use of tiny channels to speed up analyses of biomolecules such as DNA and proteins.

Blanca H. Lapizco-Encinas, Rochester Institute of Technology

When you think of electric fields, you likely think of electricity – the stuff that makes modern life possible by powering everything from household appliances to cellphones. Researchers have been studying the principles of electricity since the 1600s. Benjamin Franklin, famous for his kite experiment, demonstrated that lightning was indeed electrical.

Electricity has also enabled major advances in biology. A technique called electrophoresis allows scientists to analyze the molecules of life – DNA and proteins – by separating them by their electrical charge. Electrophoresis is not only commonly taught in high school biology, but it’s also a workhorse of many clinical and research laboratories, including mine.

I am a biomedical engineering professor who works with miniaturized electrophoretic systems. Together, my students and I develop portable versions of these devices that rapidly detect pathogens and help researchers fight against them.

What is electrophoresis?

Researchers discovered electrophoresis in the 19th century by applying an electric voltage to clay particles and observing how they migrated through a layer of sand. After further advances during the 20th century, electrophoresis became standard in laboratories.

To understand how electrophoresis works, we first need to explain electric fields. These are invisible forces that electrically charged particles, such as protons and electrons, exert on each other. A particle with a positive electrical charge, for example, would be attracted toward a particle with a negative charge. The law of “opposites attract” applies here. Molecules can also have a charge; whether it’s more positive or negative depends on the types of atoms that make it up.

In electrophoresis, an electric field is generated between two electrodes connected to a power supply. One electrode has a positive charge and the other has a negative charge. They are positioned on opposite sides of a container filled with water and a little bit of salt, which can conduct electricity.

When charged molecules such as DNA and proteins are present in the water, the electrodes create a force field between them that pushes the charged particles toward the oppositely charged electrode. This process is called electrophoretic migration.

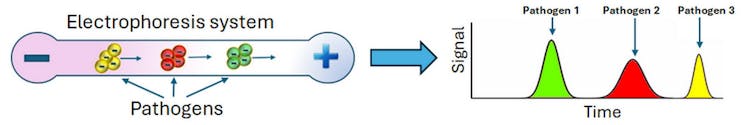

Pathogens have distinct electrical charges and can be separated by measuring how quickly they move through electrophoresis. Blanca H. Lapizco-Encinas, CC BY-SA

Researchers like electrophoresis because it is fast and flexible. Electrophoresis can help analyze distinct types of particles, from molecules to microbes. Further, electrophoresis can be carried out with materials such as paper, gels and thin tubes.

In 1972, physicist Stanislav Dukhin and his colleagues observed another type of electrophoretic migration called nonlinear electrophoresis that could separate particles not only by their electrical charge but also by their size and shape.

Electric fields and pathogens

Further advancements in electrophoresis have made it a useful tool to fight pathogens. In particular, the microfluidics revolution made possible the tiny laboratories that allow researchers to rapidly detect pathogens.

In 1999, researchers found that these tiny electrophoresis systems could also separate intact pathogens by differences in their electrical charge. They placed a mixture of several types of bacteria in a very thin glass capillary that was then exposed to an electric field. Some bacteria exited the device faster than others due to their distinct electrical charges, making it possible to separate the microbes by type. Measuring their migration speeds allowed scientists to identify each species of bacteria present in the sample through a process that took less than 20 minutes.

Microfluidics improved this process even further. Microfluidic devices are small enough to fit in the palm of your hand. Their miniature size allows them to perform analyses much faster than conventional laboratory equipment because particles don’t need to travel that far through the device to be analyzed. This means the molecules or pathogens researchers are looking for are more easily detected and less likely to be lost during analysis.

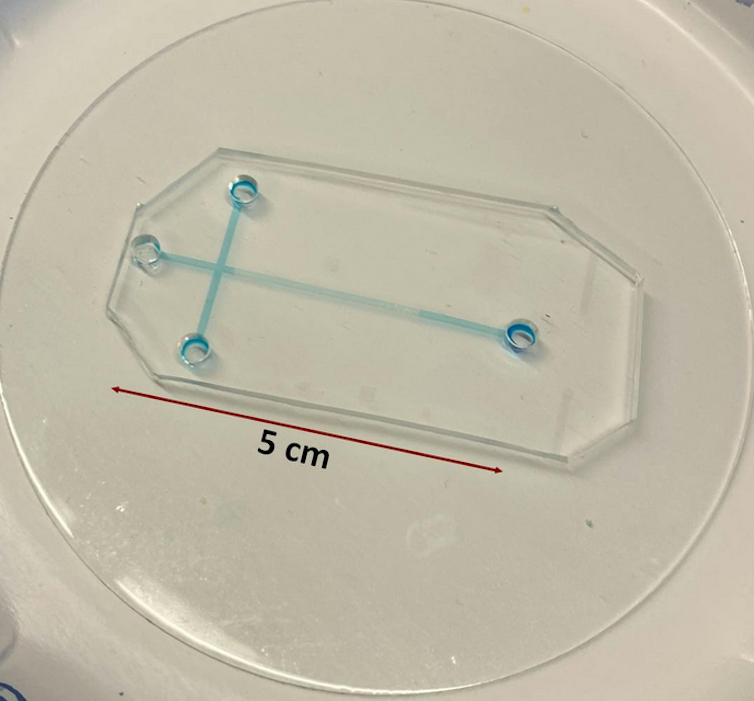

This is an example of a microfluidic electrophoresis device the author uses in her lab. Alaleh Vaghef-Koodehi, CC BY-SA

For example, samples analyzed using conventional electrophoresis systems would need to travel through capillary tubes that are about 11 to 31 inches (30 to 80 centimeters) long. These can take 40 to 50 minutes to process and are not portable. In comparison, samples analyzed with tiny electrophoresis systems migrate through microchannels that are only 0.4 to 2 inches (1 to 5 centimeters) long. This translates to small, portable devices with analysis times of about two to three minutes.

Nonlinear electrophoresis has enabled more powerful devices by allowing researchers to separate and detect pathogens by their size and shape. My lab colleagues and I showed that combining nonlinear electrophoresis with microfluidics can not only separate distinct types of bacterial cells but also live and dead bacterial cells.

Tiny electrophoresis systems in medicine

Microfluidic electrophoresis has the potential to be useful across industries. Primarily, these small systems can replace conventional analysis methods with faster results, greater convenience and lower cost.

For example, when testing the efficacy of antibiotics, these tiny devices could help researchers quickly tell whether pathogens are dead after treatment. It could also help doctors decide which drug is most appropriate for a patient by quickly distinguishing between normal bacteria and antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

My lab is also working on developing microelectrophoresis systems for purifying bacteriophage viruses that can be used to treat bacterial infections.

With further development, the power of electric fields and microfluidics can speed up how researchers detect and fight pathogens.

Blanca H. Lapizco-Encinas, Professor of Biomedical Engineering, Rochester Institute of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.