A fusion experiment ran so hot that the wall materials facing the plasma retained defects.

Sophie Blondel, University of Tennessee

Fusion energy has the potential to be an effective clean energy source, as its reactions generate incredibly large amounts of energy. Fusion reactors aim to reproduce on Earth what happens in the core of the Sun, where very light elements merge and release energy in the process. Engineers can harness this energy to heat water and generate electricity through a steam turbine, but the path to fusion isn’t completely straightforward.

Controlled nuclear fusion has several advantages over other power sources for generating electricity. For one, the fusion reaction itself doesn’t produce any carbon dioxide. There is no risk of meltdown, and the reaction doesn’t generate any long-lived radioactive waste.

I’m a nuclear engineer who studies materials that scientists could use in fusion reactors. Fusion takes place at incredibly high temperatures. So to one day make fusion a feasible energy source, reactors will need to be built with materials that can survive the heat and irradiation generated by fusion reactions.

Fusion material challenges

Several types of elements can merge during a fusion reaction. The one most scientists prefer is deuterium plus tritium. These two elements have the highest likelihood of fusing at temperatures that a reactor can maintain. This reaction generates a helium atom and a neutron, which carries most of the energy from the reaction.

Humans have successfully generated fusion reactions on Earth since 1952 – some even in their garage. But the trick now is to make it worth it. You need to get more energy out of the process than you put in to initiate the reaction.

Fusion reactions happen in a very hot plasma, which is a state of matter similar to gas but made of charged particles. The plasma needs to stay extremely hot – over 100 million degrees Celsius – and condensed for the duration of the reaction.

To keep the plasma hot and condensed and create a reaction that can keep going, you need special materials making up the reactor walls. You also need a cheap and reliable source of fuel.

While deuterium is very common and obtained from water, tritium is very rare. A 1-gigawatt fusion reactor is expected to burn 56 kilograms of tritium annually. But the world has only about 25 kilograms of tritium commercially available.

Researchers need to find alternative sources for tritium before fusion energy can get off the ground. One option is to have each reactor generating its own tritium through a system called the breeding blanket.

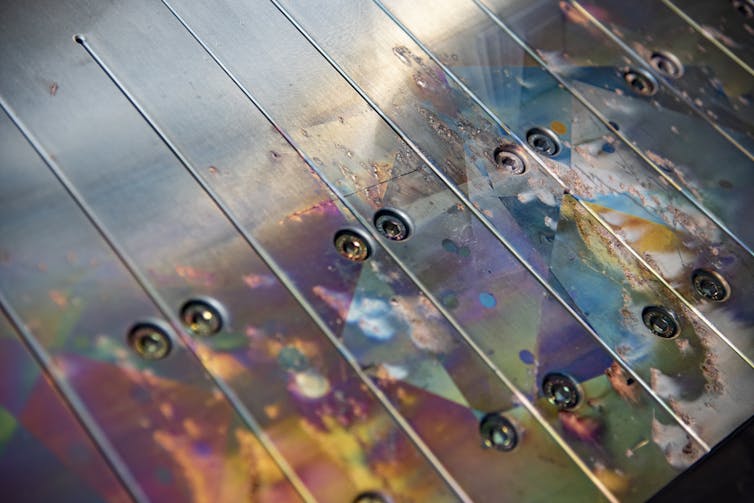

The breeding blanket makes up the first layer of the plasma chamber walls and contains lithium that reacts with the neutrons generated in the fusion reaction to produce tritium. The blanket also converts the energy carried by these neutrons to heat.

Fusion devices also need a divertor, which extracts the heat and ash produced in the reaction. The divertor helps keep the reactions going for longer.

These materials will be exposed to unprecedented levels of heat and particle bombardment. And there aren’t currently any experimental facilities to reproduce these conditions and test materials in a real-world scenario. So, the focus of my research is to bridge this gap using models and computer simulations.

From the atom to full device

My colleagues and I work on producing tools that can predict how the materials in a fusion reactor erode, and how their properties change when they are exposed to extreme heat and lots of particle radiation.

As they get irradiated, defects can form and grow in these materials, which affect how well they react to heat and stress. In the future, we hope that government agencies and private companies can use these tools to design fusion power plants.

Our approach, called multiscale modeling, consists of looking at the physics in these materials over different time and length scales with a range of computational models.

We first study the phenomena happening in these materials at the atomic scale through accurate but expensive simulations. For instance, one simulation might examine how hydrogen moves within a material during irradiation.

From these simulations, we look at properties such as diffusivity, which tells us how much the hydrogen can spread throughout the material.

We can integrate the information from these atomic level simulations into less expensive simulations, which look at how the materials react at a larger scale. These larger-scale simulations are less expensive because they model the materials as a continuum instead of considering every single atom.

The atomic-scale simulations could take weeks to run on a supercomputer, while the continuum one will take only a few hours.

All this modeling work happening on computers is then compared with experimental results obtained in laboratories.

For example, if one side of the material has hydrogen gas, we want to know how much hydrogen leaks to the other side of the material. If the model and the experimental results match, we can have confidence in the model and use it to predict the behavior of the same material under the conditions we would expect in a fusion device.

If they don’t match, we go back to the atomic-scale simulations to investigate what we missed.

Additionally, we can couple the larger-scale material model to plasma models. These models can tell us which parts of a fusion reactor will be the hottest or have the most particle bombardment. From there, we can evaluate more scenarios.

For instance, if too much hydrogen leaks through the material during the operation of the fusion reactor, we could recommend making the material thicker in certain places, or adding something to trap the hydrogen.

Designing new materials

As the quest for commercial fusion energy continues, scientists will need to engineer more resilient materials. The field of possibilities is daunting – engineers can manufacture multiple elements together in many ways.

You could combine two elements to create a new material, but how do you know what the right proportion is of each element? And what if you want to try mixing five or more elements together? It would take way too long to try to run our simulations for all of these possibilities.

Thankfully, artificial intelligence is here to assist. By combining experimental and simulation results, analytical AI can recommend combinations that are most likely to have the properties we’re looking for, such as heat and stress resistance.

The aim is to reduce the number of materials that an engineer would have to produce and test experimentally to save time and money.![]()

Sophie Blondel, Research Assistant Professor of Nuclear Engineering, University of Tennessee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.