It can take a lot of effort to understand the many different Medicare choices.

Grace McCormack, University of Southern California and Melissa Garrido, Boston University

The 67 million Americans eligible for Medicare make an important decision every October: Should they make changes in their Medicare health insurance plans for the next calendar year?

The decision is complicated. Medicare has an enormous variety of coverage options, with large and varying implications for people’s health and finances, both as beneficiaries and taxpayers. And the decision is consequential – some choices lock beneficiaries out of traditional Medicare.

Beneficiaries choose an insurance plan when they turn 65 or become eligible based on qualifying chronic conditions or disabilities. After the initial sign-up, most beneficiaries can make changes only during the open enrollment period each fall.

The 2024 open enrollment period, which runs from Oct. 15 to Dec. 7, marks an opportunity to reassess options. Given the complicated nature of Medicare and the scarcity of unbiased advisers, however, finding reliable information and understanding the options available can be challenging.

We are health care policy experts who study Medicare, and even we find it complicated. One of us recently helped a relative enroll in Medicare for the first time. She’s healthy, has access to health insurance through her employer and doesn’t regularly take prescription drugs. Even in this straightforward scenario, the number of choices were overwhelming.

The stakes of these choices are even higher for people managing multiple chronic conditions. There is help available for beneficiaries, but we have found that there is considerable room for improvement – especially in making help available for everyone who needs it.

The choice is complex, especially when you are signing up for the first time and if you are eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid. Insurers often engage in aggressive and sometimes deceptive advertising and outreach through brokers and agents. Choose unbiased resources to guide you through the process, like www.shiphelp.org. Make sure to start before your 65th birthday for initial sign-up, look out for yearly plan changes, and start well before the Dec. 7 deadline for any plan changes.

2 paths with many decisions

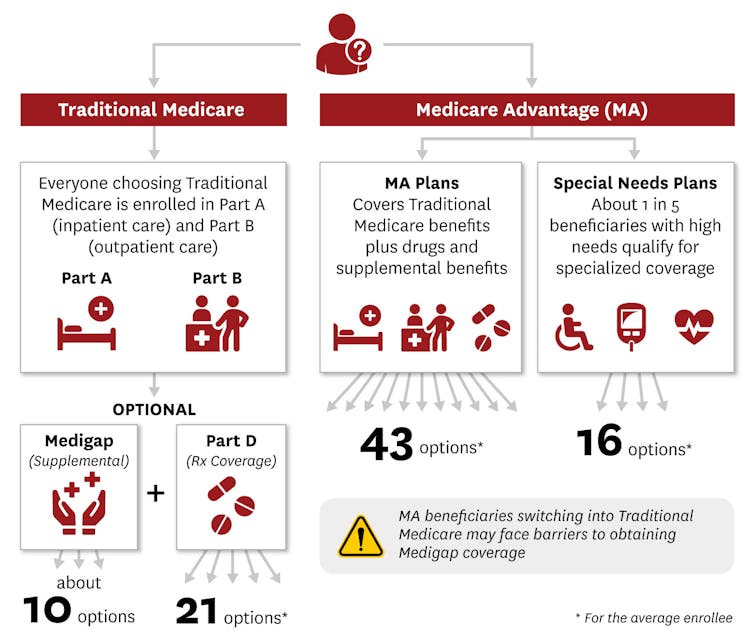

Within Medicare, beneficiaries have a choice between two very different programs. They can enroll in either traditional Medicare, which is administered by the government, or one of the Medicare Advantage plans offered by private insurance companies.

Within each program are dozens of further choices.

Traditional Medicare is a nationally uniform cost-sharing plan for medical services that allows people to choose their providers for most types of medical care, usually without prior authorization. Deductibles for 2024 are US$1,632 for hospital costs and $240 for outpatient and medical costs. Patients also have to chip in starting on Day 61 for a hospital stay and Day 21 for a skilled nursing facility stay. This percentage is known as coinsurance. After the yearly deductible, Medicare pays 80% of outpatient and medical costs, leaving the person with a 20% copayment. Traditional Medicare’s basic plan, known as Part A and Part B, also has no out-of-pocket maximum.

People enrolled in traditional Medicare can also purchase supplemental coverage from a private insurance company, known as Part D, for drugs. And they can purchase supplemental coverage, known as Medigap, to lower or eliminate their deductibles, coinsurance and copayments, cap costs for Parts A and B, and add an emergency foreign travel benefit.

Part D plans cover prescription drug costs for about $0 to $100 a month. People with lower incomes may get extra financial help by signing up for the Medicare program Part D Extra Help or state-sponsored pharmaceutical assistance programs.

There are 10 standardized Medigap plans, also known as Medicare supplement plans. Depending on the plan, and the person’s gender, location and smoking status, Medigap typically costs from about $30 to $400 a month when a beneficiary first enrolls in Medicare.

The Medicare Advantage program allows private insurers to bundle everything together and offers many enrollment options. Compared with traditional Medicare, Medicare Advantage plans typically offer lower out-of-pocket costs. They often bundle supplemental coverage for hearing, vision and dental, which is not part of traditional Medicare.

But Medicare Advantage plans also limit provider networks, meaning that people who are enrolled in them can see only certain providers without paying extra. In comparison to traditional Medicare, Medicare Advantage enrollees on average go to lower-quality hospitals, nursing facilities, and home health agencies but see higher-quality primary care doctors.

Medicare Advantage plans also often require prior authorization – often for important services such as stays at skilled nursing facilities, home health services and dialysis.

Choice overload

Understanding the tradeoffs between premiums, health care access and out-of-pocket health care costs can be overwhelming.

Turning 65 begins the process of taking one of two major paths, which each have a thicket of health care choices. Rika Kanaoka/USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics

Though options vary by county, the typical Medicare beneficiary can choose between as many as 10 Medigap plans and 21 standalone Part D plans, or an average of 43 Medicare Advantage plans. People who are eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid, or have certain chronic conditions, or are in a long-term care facility have additional types of Medicare Advantage plans known as Special Needs Plans to choose among.

Medicare Advantage plans can vary in terms of networks, benefits and use of prior authorization.

Different Medicare Advantage plans have varying and large impacts on enrollee health, including dramatic differences in mortality rates. Researchers found a 16% difference per year between the best and worst Medicare Advantage plans, meaning that for every 100 people in the worst plans who die within a year, they would expect only 84 people to die within that year if all had been enrolled in the best plans instead. They also found plans that cost more had lower mortality rates, but plans that had higher federal quality ratings – known as “star ratings” – did not necessarily have lower mortality rates.

The quality of different Medicare Advantage plans, however, can be difficult for potential enrollees to assess. The federal plan finder website lists available plans and publishes a quality rating of one to five stars for each plan. But in practice, these star ratings don’t necessarily correspond to better enrollee experiences or meaningful differences in quality.

Online provider networks can also contain errors or include providers who are no longer seeing new patients, making it hard for people to choose plans that give them access to the providers they prefer.

While many Medicare Advantage plans boast about their supplemental benefits , such as vision and dental coverage, it’s often difficult to understand how generous this supplemental coverage is. For instance, while most Medicare Advantage plans offer supplemental dental benefits, cost-sharing and coverage can vary. Some plans don’t cover services such as extractions and endodontics, which includes root canals. Most plans that cover these more extensive dental services require some combination of coinsurance, copayments and annual limits.

Even when information is fully available, mistakes are likely.

Part D beneficiaries often fail to accurately evaluate premiums and expected out-of-pocket costs when making their enrollment decisions. Past work suggests that many beneficiaries have difficulty processing the proliferation of options. A person’s relationship with health care providers, financial situation and preferences are key considerations. The consequences of enrolling in one plan or another can be difficult to determine.

The trap: Locked out

At 65, when most beneficiaries first enroll in Medicare, federal regulations guarantee that anyone can get Medigap coverage. During this initial sign-up, beneficiaries can’t be charged a higher premium based on their health.

Older Americans who enroll in a Medicare Advantage plan but then want to switch back to traditional Medicare after more than a year has passed lose that guarantee. This can effectively lock them out of enrolling in supplemental Medigap insurance, making the initial decision a one-way street.

For the initial sign-up, Medigap plans are “guaranteed issue,” meaning the plan must cover preexisting health conditions without a waiting period and must allow anyone to enroll, regardless of health. They also must be “community rated,” meaning that the cost of a plan can’t rise because of age or illness, although it can go up due to other factors such as inflation.

People who enroll in traditional Medicare and a supplemental Medigap plan at 65 can expect to continue paying community-rated premiums as long as they remain enrolled, regardless of what happens to their health.

In most states, however, people who switch from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare don’t have as many protections. Most state regulations permit plans to deny coverage, impose waiting periods or charge higher Medigap premiums based on their expected health costs. Only Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts and New York guarantee that people can get Medigap plans after the initial sign-up period.

Deceptive advertising

Information about Medicare coverage and assistance choosing a plan is available but varies in quality and completeness. Older Americans are bombarded with ads for Medicare Advantage plans that they may not be eligible for and that include misleading statements about benefits.

A November 2022 report from the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance found deceptive and aggressive sales and marketing tactics, including mailed brochures that implied government endorsement, telemarketers who called up to 20 times a day, and salespeople who approached older adults in the grocery store to ask about their insurance coverage.

The Department of Health and Human Services tightened rules for 2024, requiring third-party marketers to include federal resources about Medicare, including the website and toll-free phone number, and limiting the number of contacts from marketers.

Although the government has the authority to review marketing materials, enforcement is partially dependent on whether complaints are filed. Complaints can be filed with the federal government’s Senior Medicare Patrol, a federally funded program that prevents and addresses unethical Medicare activities.

Meanwhile, the number of people enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans has grown rapidly, doubling since 2010 and accounting for more than half of all Medicare beneficiaries by 2023.

Nearly one-third of Medicare beneficiaries seek information from an insurance broker. Brokers sell health insurance plans from multiple companies. However, because they receive payment from plans in exchange for sales, and because they are unlikely to sell every option, a plan recommended by a broker may not meet a person’s needs.

Help is out there − but falls short

An alternative source of information is the federal government. It offers three sources of information to assist people with choosing one of these plans: 1-800-Medicare, medicare.gov and the State Health Insurance Assistance Program, also known as SHIP.

The SHIP program combats misleading Medicare advertising and deceptive brokers by connecting eligible Americans with counselors by phone or in person to help them choose plans. Many people say they prefer meeting in person with a counselor over phone or internet support. SHIP staff say they often help people understand what’s in Medicare Advantage ads and disenroll from plans they were directed to by brokers.

Telephone SHIP services are available nationally, but one of us and our colleagues have found that in-person SHIP services are not available in some areas. We tabulated areas by ZIP code in 27 states and found that although more than half of the locations had a SHIP site within the county, areas without a SHIP site included a larger proportion of people with low incomes.

Virtual services are an option that’s particularly useful in rural areas and for people with limited mobility or little access to transportation, but they require online access. Virtual and in-person services, where both a beneficiary and a counselor can look at the same computer screen, are especially useful for looking through complex coverage options.

We also interviewed SHIP counselors and coordinators from across the U.S.

As one SHIP coordinator noted, many people are not aware of all their coverage options. For instance, one beneficiary told a coordinator, “I’ve been on Medicaid and I’m aging out of Medicaid. And I don’t have a lot of money. And now I have to pay for my insurance?” As it turned out, the beneficiary was eligible for both Medicaid and Medicare because of their income, and so had to pay less than they thought.

The interviews made clear that many people are not aware that Medicare Advantage ads and insurance brokers may be biased. One counselor said, “There’s a lot of backing (beneficiaries) off the ledge, if you will, thanks to those TV commercials.”

Many SHIP staff counselors said they would benefit from additional training on coverage options, including for people who are eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid. The SHIP program relies heavily on volunteers, and there is often greater demand for services than the available volunteers can offer. Additional counselors would help meet needs for complex coverage decisions.

The key to making a good Medicare coverage decision is to use the help available and weigh your costs, access to health providers, current health and medication needs, and also consider how your health and medication needs might change as time goes on.

This article is part of an occasional series examining the U.S. Medicare system.

This story has been updated to remove a graphic that contained incorrect information about SHIP locations, and to correct the date of the open enrollment period.

Grace McCormack, Postdoctoral researcher of Health Policy and Economics, University of Southern California and Melissa Garrido, Research Professor, Health Law, Policy & Management, Boston University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.