Philip Matich

James Marcus Drymon, Mississippi State University; Lindsay Mullins, Mississippi State University, and Philip Matich, Texas A&M University

In late spring, estuaries along the U.S. Gulf Coast come alive with newborn fish and other sea life. While some species have struggled to adjust to the region’s rising water temperatures in recent years, one is thriving: juvenile bull sharks.

We study this iconic shark species, named for its stout body and matching disposition, along the Gulf of Mexico. Over the past two decades, we have documented a fivefold increase in baby bull sharks in Mobile Bay, Alabama, and a similar rise in several Texas estuaries, as our new study shows.

Despite the bull shark’s fearsome reputation, baby bull sharks are not cause for concern for humans in these waters.

While adult bull sharks are responsible for an occasional unprovoked attack, baby bull sharks haven’t fully developed the skills needed to hunt larger prey. And you’re still far more likely to be killed by bees, wasps or snakes than sharks.

The fascinating life of a young bull shark

Most sharks are fully marine and spend their entire lives in the ocean. Bull sharks, however, are one of a handful of shark species that use freshwater environments as nurseries.

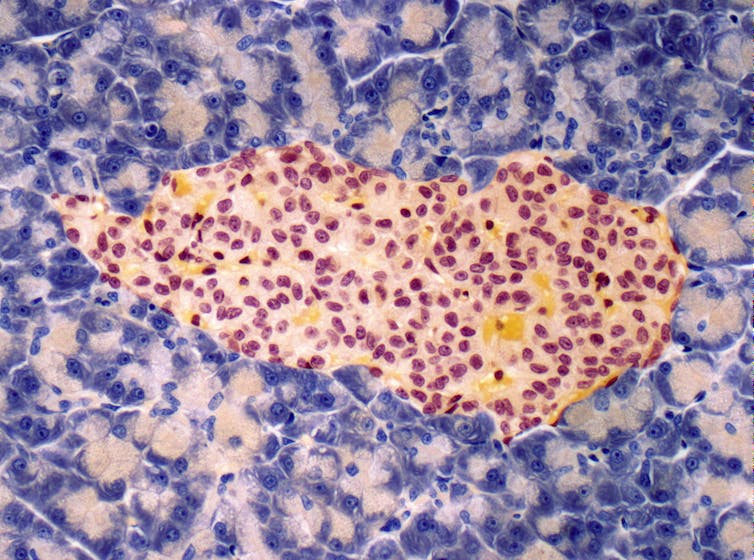

Baby bull sharks have been found in the Alabama River, 75 miles north of the ocean, and up the Mississippi River as far as Illinois. They have evolved to tolerate fresh water by reducing the need for salts and urea in their bodies compared to marine sharks, and actively taking in more salts through their food and across their gills.

In Texas, young bull shark numbers have been increasing in estuaries like Galveston Bay and Sabine Lake over the past 40 years, particularly where rivers like the Trinity, Sabine and Neches intersect with these ecosystems. These areas may offer protection from predators, such as bigger sharks.

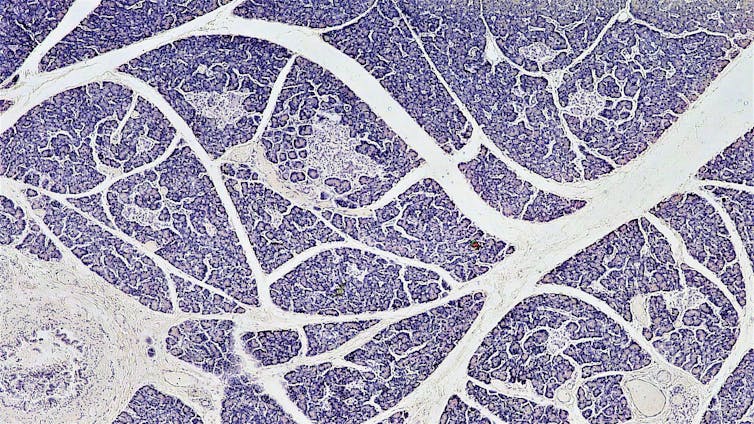

Albert Kok via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

The presence of bull sharks in these estuaries also contributes to their health and stability.

Because bull sharks frequently move between freshwater and marine ecosystems, they can act as mobile links that connect these two aquatic environments. Bull sharks often feed in one environment, salty water for example, and then rest and excrete nutrients in freshwater bays. Feeding and resting in different locations can improve the ability of these ecosystems to withstand disturbances like warming weather conditions, because if one habitat is disturbed, the other is still supported.

Like a spider web, food webs are connected by many intersecting threads. The more threads, the stronger the web. The use of both freshwater and marine habitats by bull sharks increases the number of these threads through their predator-prey interactions, thereby strengthening the ecosystem.

Waters are warming

As the planet warms, coastal ocean temperatures are rising. In the Gulf of Mexico, water temperatures have risen more than 3 degrees Fahrenheit (more than 1.5 degrees Celsius) due to climate change.

On a global scale, warming waters are harming more fish species than they are helping. Higher temperatures increase food requirements and stress levels, while making fish more susceptible to disease and reducing the survival of their young. A variety of fish populations in the Gulf of Mexico, including mullet and flounder, have declined as warmer conditions affected their spawning.

At the same time, the waters used by baby bull sharks have expanded in part due to this warming, creating a dynamic habitat.

An easy way to understand how sharks use dynamic habitat is to capture them with nets and measure the characteristics of the surrounding environment. In our sampling data, we could see that the mean annual water temperatures on the Alabama and Texas coasts increased at the same time the bull shark populations rose.

In coastal Alabama, we found that the relative abundance of baby bull sharks has increased fivefold over the past 20 years. Slight increases in temperature over that time provided the best explanation for this population increase.

Of all the temperatures recorded in that study, there was no maximum temperature threshold detected for baby bull sharks. So far, at least since 2003, it’s been “the warmer the better” for a baby bull shark.

We observed a similar trend in coastal Texas from Sabine Lake to Matagorda Bay, where warming estuaries supported increased abundances of baby bull sharks up to eightfold over the past 40 years. Warmer waters allowed baby bull sharks to remain in their natal estuaries longer during their first year before overwintering in the Gulf of Mexico, increasing their survival to the next life stage.

Collectively, our recent studies indicate that warming waters are currently beneficial for young bull sharks. But just like your favorite dessert, too much of a good thing can be detrimental.

All animals, including bull sharks, have maximum and minimum temperatures at which they can function. If temperatures get too hot or too cold, this can lead to problems, whether through direct stress on the shark’s bodily functions or on its ecosystem at large.

Some of our previous work from Florida shows that baby bull sharks will leave coastal nurseries in response to episodic cold snaps to avoid cold-stress. Sharks that didn’t leave died. The same may be true for hot temperatures, although conditions have not yet reached that point in the Gulf of Mexico based on our research.

A changing world

It’s clear that climate change is altering coastal ecosystems. Our work shows the direct benefit to young bull sharks, but how the observed population growth is affecting other species in the coastal estuaries remains to be seen.

Saving the Blue

The rise in bull sharks may affect other fish species, including bull shark prey like mullets, drums, herrings and catfish. More bull sharks could eventually mean fewer of the fish that humans rely on. In warmer water, sharks burn more energy.

Ultimately, tracking how the distributions of species like bull sharks change over time remains a critical priority for understanding future shifts in fish populations and the health of our coastal ecosystems.![]()

James Marcus Drymon, Associate Extension Professor in Marine Fisheries Ecology, Mississippi State University; Lindsay Mullins, Ph.D. Student in Marine Science, Mississippi State University, and Philip Matich, Instructional Assistant Professor of Marine Biology, Texas A&M University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.