Mississippi Today

Is Mississippi’s parole system broken?

This is the first of a year-long look at Mississippi's parole system.

At 17, James Williams III shot and killed his father and stepmother in south Jackson, stuffed their bodies into plastic containers and dumped them in the woods in a different county.

In 2023 after he'd served nearly 20 years of a life sentence, Mississippi's Parole Board freed him, two years after the previous board denied his request. He was 38 years old.

The decision came as a shock to family members of his victims, lawmakers and members of law enforcement who called on the Parole Board without success to reverse its decision.

Williams' parole also caught the attention of advocates helping those who have served longer behind bars and been denied parole multiple times, despite similarly participating in rehabilitative, educational and spiritual programs to show that they've changed.

“You can all have all the facts there and hear two or three different versions and accounts of the situations and when you see that someone has actually taken advantage of stuff, [and] is not the same person they were,” Parole Board Jeffery Belk said in an interview to explain how the board makes decisions.

Despite making all the same efforts as Williams, thousands of people have remained in prison instead of receiving parole. The parole grant rate that averaged 62% between 2013 and 2021 fell to 35% in 2022 when Belk and new members joined the Parole Board, according to data from the Mississippi Department of Corrections.

At the same time, the board has held fewer hearings since 2022 and is using more and longer setoffs, the period between parole hearings.

Among those denied parole is 65-year-old Anita Krecic, in prison since 1989 for her role in the murder of Highway Patrol Trooper David Bruce Ladner in Harrison County, for which she has maintained she was present for but did not participate. The trooper's shooter, Krecic's boyfriend Tracy Alan Hansen, was executed over 20 years ago.

Krecic stopped using drugs in prison, enrolled in college-level classes and took vocational courses like computer repair.

The Parole Board denied her release in 2022 – the 10th time since she became parole eligible. Her next hearing is sometime in 2030, according to court records. She will then be nearly 70 years old.

“I have a cabinet full of (records of) people who are honestly trying and are trying to do better and do better,” said Mitzi Magleby, an advocate working with Krecic and other incarcerated people to navigate the parole process.

Magleby is among advocates, family members and incarcerated people who see these disparate decisions as a sign that Mississippi's parole system is broken.

Inconsistencies with who is paroled, the use of long setoffs and infrequent use of other forms of medical or compassionate release keep people inside, contributing to the growth of Mississippi's prison population. Logistical issues create a bottleneck of those who could be released but can't partly due to a lack of caseworkers and plans they generate, which are a required part of parole.

Even after release, they encounter a supervision system with a high number of vacancies and the many challenges of reentry, including a lack of transitional housing.

A 2023 Prison Policy Initiative report that looked at parole outcomes across 27 states found that the COVID-19 pandemic led to a change in parole grant rates. But, while the average change in rates from 2019 to 2022 was a 14% decrease, Mississippi's was 45%.

Additionally, the review found that the number of parole hearings and overall releases decreased in most states in the past five years.

Mississippi halted new prison admissions and saw its prison population fall early in the pandemic, but the population has returned to pre-pandemic levels as the Parole Board has scaled back releases.

Researchers at the Robina Institute of Criminal Law and Criminal Justice at the University of Minnesota studing parole release and revocation across the country also found that parole grant rates plummeted in 2022.

“COVID caused a massive change to the makeup of the prison population,” said Robina research director Julia Laskorunsky. “To me, it makes sense most states would have a higher denial rate following COVID and it would rebound back to the norm.”

But in Mississippi, it hasn't.

Parole is the main way people are released from the Mississippi prison system, accounting for over 60% of all releases since at least 2017, according to a 2021 report by the Joint Legislative Committee on Performance Evaluation and Expenditure Review.

Between 2013 and 2023, the board granted parole to over 52,000 people, averaging about 4,700 people each year, according to a review of MDOC parole data.

Nearly 6,000 people were paroled in 2016, a high during the 10-year period.

“Looking at the success (of people's rehabilitation) is the primary job,” said Steve Pickett, who served as Parole Board chair from 2013-2021.

A parole grant is the first step. Typically, the wait time between parole and release is two weeks.

More than 95% of the over 56,000 people granted parole within the past decade had a nonviolent charge as their primary offense, such as drug possession, burglary and felony DUI, according to MDOC data.

Those with a primary nonviolent offense also made up the bulk of parole denials because there are more people incarcerated for nonviolent and drug crimes compared to violent and sex crimes. There are also less crimes defined as violent compared to nonviolent crimes.

However, homicide remains the most common primary charge among the 31,000 denied parole – nearly 12% of all denial outcomes, according to MDOC data.

As an integral part of the criminal justice system, Pickett said the board can serve as a release valve when the prison population is overwhelmed and it acts as a group of social workers and judges to determine whether a person can be freed.

When he retired, the prison population had fallen below 17,000, mostly in response to MDOC freezing the transfer of people from county jails during the early days of the pandemic. By the end of 2022, the population returned to pre-pandemic levels above 19,000.

The decade's low of about 2,150 people granted parole came in 2022, when the board's chairman and membership changed, the data shows.

“We're not a numbers-driven board,” Belk said, noting that he stepped into the role without an agenda. “I've made that very clear in the past several years.”

He became chairman on the heels of a wave of parole grants and criminal justice reforms designed to increase parole eligibility for an estimated 5,700 additional inmates.

People wondered why the new iteration of the board wasn't paroling as many people compared to previous years. Belk said the board is trying to exercise better due diligence to grant parole, which he said includes having all available information about a person and their case and completed and substantive case plans from MDOC.

“No, we actually took the time to review and try to get these systems and processes in place to where people can be set up for success,” he said.

When denying parole, the board typically uses setoff periods, the length of time between hearings.

In 2022, 1,404 people were set off to the end of their sentence – the highest in the 10-year period. Belk said most of the people the board has set off to duration are those with short sentences who were expected to be released within weeks, months or years, as opposed to decades.

The board also decides whether to revoke parole for those found to violate the terms of their release, especially after arrest or conviction of a new crime.

The year Belk became chairman, the board revoked parole for over 2,100 people, a 90% increase from 2021, when the board revoked parole for closer to 1,100 people, according to MDOC data.

The board continued parole for more than 1,000 people for back-to-back years in 2020 and 2021. The new board continued parole for less than 100 people in 2022 and in 2023, according to MDOC data.

About two-thirds of Missisisppi's prison population is now eligible for parole, partly because of legislation passed in the last two decades.

Those convicted of nonviolent offenses or drug offenses were already eligible after serving 25% or 10 years of their sentence. Reforms passed in 2021 expanded parole eligibility to those convicted of violent offenses, with most needing to serve at least half or 20 years of their sentence or 60% or 25 years for specific crimes such as carjacking.

Criminal justice groups from both political parties that support the reforms say nearly all of the 2,150 people who became eligible for parole under Senate Bill 2795 did not return to prison on a new sentence within the first two years of their release, according to an analysis by FWD.us, a bipartisan criminal justice and immigration advocacy group.

This year, the governor signed into law a bill that extends the parole eligibility reforms for two more years.

Despite the successes, advocates have said the law is not being fully used. FWD.us said the impact of expanding parole in 2021 was short-lived because it was not fully implemented, according to a report released ahead of the recent legislative session.

“The Parole Board plays an essential role in ensuring the state's parole law is fully implemented,” said Mississippi State Director Alesha Judkins in a statement.

Once parole eligible, a individual applies for consideration. Four months ahead of their eligibility date, the board gathers information to make a determination, such as the circumstances of their crime, previous criminal record, conduct during incarceration and participation in prison programming.

The board also approves a person's case plan and sees whether they will have family or community support or a job lined up after prison.

“If someone has done what they are supposed to do and taken advantage of the different opportunities at MDOC, it's kind of what have you done to make yourself parolable?” Belk said.

“What have you done to set yourself up for success?”

But success is subjective, in the eyes of the board. People have come to their parole hearings with multiple certificates of courses and programs they have completed, but Belk said the board didn't always see them as meaningful.

Although he couldn't substantiate the allegation, he said some program instructors would sign all the certificates and hand them out at the beginning of a course instead of teaching, which showed that some of the programs lacked credibility.

“Most of the time it was a participation trophy,” said Belk, who spoke anecdotally about what the board has been told by MDOC staff and innates during parole and revocation hearings.

Under Corrections Commissioner Burl Cain, Belk said courses are now being taught and documented in a standardized way, giving the board a piece of mind that inmates are learning and growing by participating in them.

Parole hearings are more often a file review completed in the board's Jackson office. The person up for parole can attend the hearing via live video, including if they have legal representation and if a hearing is requested, but most do not attend.

In 2021, PEER released a report that painted what Belk saw as a “picture of an agency in disarray.” The report found the board held untimely hearings and was not effectively using presumptive parole for nonviolent offenders who have met certain requirements and doesn't require a hearing.

A followup PEER report in June 2023 found the board was holding timely hearings but still wsn't effectively using presumptive parole or keeping meeting minutes. Belk said the board is working with MDOC to get systems, policies and procedures in place for presumptive parole to operate, which it hasn't since it was made law in 2014.

“The (MDOC) commissioner uses the phrase ‘It's like a caterpillar crawl out.' I use the phrase ‘It's like trying to push a string,'” he said about getting things in order.

Once presumptive parole is running, Belk said the board will have more time to focus on considering parole for violent offenders, including those sentenced to life with the possibility of parole before 1995.

Wanda Bertram, spokesperson for the Prison Policy Initiative, said research shows that people convicted of life sentences, even serious violent offenses and sexual offenses, have the lowest recidivism rates and, along with the elderly, are least likely to return to prison.

“As counterintuitive as it seems, that is good policy to focus on lifers,” she said.

Belk said the board tries to see the nuances in each individual case or each time a person comes up for parole, which can be multiple times before release.

Sometimes, people are good talkers and charmers with a prepared speech about how much they have changed during incarceration, so Belk said the board has to distinguish between fact and fiction, action and words.

There are people who decided they no longer wanted to be the version of themselves who were convicted and sentenced. They have completed high school equivalent and college degrees, found religion, learned a trade – sometimes all three.

When they talk about what they've done, Belk said you can tell they've changed, or they say they are at peace and content with whatever decision the board makes about their parole.

That brings back the discussion of James Williams III, and before him, Frederick Bell.

In 2022, the board voted to parole Frederick Bell, who was convicted of shooting 21-year-old Robert “Bert” Bell (no relation) during a 1991 store robbery in Grenada County. He had originally been sentenced to death, but was resentenced to life with parole eligibility.

In prison, Bell served as a mentor, teacher and pastor.

The decision shocked Bert Bell's family, who said they had been attending Parole Board hearings since 2015 to oppose his release. Gene Bell, Bert's younger brother, said the board previously said it wouldn't parole Frederick Bell and would give him a longer setoff period until his next hearing.

Under state law, the board can't deny someone parole based solely on victim opposition.

But the board delayed Bell's September 2022 release, and the next month it rescinded his parole and gave him a two-year setoff. He remains at the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman.

In a 2023 report, the Prison Policy Initiative cited Bell's approved and rescinded release as an example of how political dynamics can influence how parole is used and applied.

Last year, the board approved parole for Williams, convicted of murdering his father, James Jr., and stepmother, Cindy Lassiter Mangum, in 2002.

Williams was originally not eligible for release but was resentenced due to U.S. Supreme Court decisions limiting life without parole for those who committed crimes when they were under the age of 18. The first time he came up for parole in 2021, he was denied, Pickett said.

The next year when he was up for parole again, Jake Howard, his attorney, told Mississippi Today's Jerry Mitchell, that Williams was “an exceptional candidate for parole” who had been part of MDOC's faith-based programs since 2008, tutored other students, became a field minister and served as a minister of music at a Parchman church.

The victims' family and lawmakers opposed Williams' release, raising concerns about public safety. This time, the opposition held no sway. Williams was released in May 2023.

Several months after his release, Williams was arrested in Rankin County for driving under the influence. He went before the board again, and had his parole revoked. To date, he is incarcerated at the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility in Pearl.

Looking back, Belk said the Bell and Williams cases were high profile and there was debate over what the facts of the case were, which he saw play out on social media and through interviews family members and lawmakers gave.

“I was not going to go on the [Paul] Gallo show to comment to the media and make a bad situation worse,” he said.

Belk declined to comment further about the men's cases, including why the board decided to keep Bell in prison but not Williams.

Generally, if someone is parole eligible, the law directs the board to consider them, regardless of their convicted offenses. That means the board can't lump all the violent offenders together and refuse to grant them parole, Belk said.

But that doesn't mean the board has to release everyone, he said. Commonalities in convictions and completion of programming doesn't always justify parol, Belk said. Neither does someone's age or how long they have been in prison.

“Just because someone has made a life change, it doesn't necessarily mean they need to be back on the streets either,” Belk said.

Both Belk and Pickett said there are situations where the board agrees someone would never be ready for parole, typically when the indivdual committed an egregious crime, like Luke Woodham, who was convicted for killing his mother and two classmates in the 1997 Pearl High School shooting and became parole eligible while Pickett served on the board.

Some of those people who are now seeking parole may have a clear behavioral record and built good relationships with prison staff, but Belk said then you look into their cases.

“The horrific details of what they've done, borderline sadistic,” he said.

It can be heartbreaking to see a victim or family emotionally scarred years or decades after losing someone, and they're asking the board not to grant parole. Belk said he has had to explain that the individuals have met parole requirements, earned good time or completed their sentence.

Pickett said even though people may be asking for different outcomes, he can see a family or parent's love for their child, whether that person was a crime victim or the incarcerated person.

“An open door is the best policy so that nobody thinks an injustice is being done, and it leads to trust in the system because if you're at last able to get a fair hearing, even if you don't like the outcome,” he said.

Magleby, the parole advocate, also sees how people grow and change, but doesn't understand how people who appear to be good candidates for release – a clear institutional record, jobs and housing lined up – have been denied parole.

Julia Norman, the newest member of the parole board, said during her February 2023 confirmation hearing that the board can vote to deny parole if they feel that the person received a sentence that was too short.

Pickett, the former chairman, said the board's job is not to resentence or determine if someone wasn't sentenced long enough. Belk said declining to parole someone and using setoffs is not a form of resentencing.

Magleby said the Parole Board has always been tough, but the former board seemed more fair and open to rehabilitation.

She has no ill will towards Williams and the fact he was paroled, but she can't help but think he got that opportunity over others who have been incarcerated for longer and have also made use of opportunities in prison to make themselves parolable.

“And why not them?” Magleby asked.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

A new law to improve pregnancy outcomes took effect Monday. But how someone can receive timely prenatal care is still unclear.

Despite presumptive Medicaid eligibility for pregnant women going into effect Monday, it's still not clear how low-income pregnant women can get the timely prenatal care the law is supposed to make possible.

House Bill 539, which was signed into law by the governor on March 12, allows eligible, low-income pregnant women to receive immediate care covered by Medicaid while they wait for their application to be officially approved by the Division of Medicaid. Applications are supposed to take no longer than 45 days to process, though recent data shows nearly a third of applications in Mississippi took longer than that, bringing pregnant women well into their first trimester – when about 80% of miscarriages occur.

The policy, which Mississippi lawmakers hope will help mitigate the state's poor maternal and infant health metrics – some of the worst in the country – exists in 29 other states and Washington D.C.

Mississippi Today reached out to the Division of Medicaid in late May to request an interview over the next month with an agency official to discuss what the process of presumptive eligibility and timely care for pregnant women would look like once the law went into effect July 1. The reporter continued each week to reach out to spokesperson Matt Westerfield, who on June 10 said the agency was “exploring some options” for the interview.

On June 28, Westerfield said implementation is “complex” and that the agency would only communicate through “written exchanges.”

The agency on Tuesday issued a general statement about its commitment to implementing the policy – with no details about any outreach, public education or provider training to date.

“The Mississippi Division of Medicaid will continue to do the necessary due diligence to ensure providers interested in making presumptive eligibility determinations are qualified and trained,” Westerfield said in an email.

Not all providers who accept Medicaid will be automatically able to participate in presumptive eligibility, according to a brief explainer on Medicaid's website posted at the end of June.

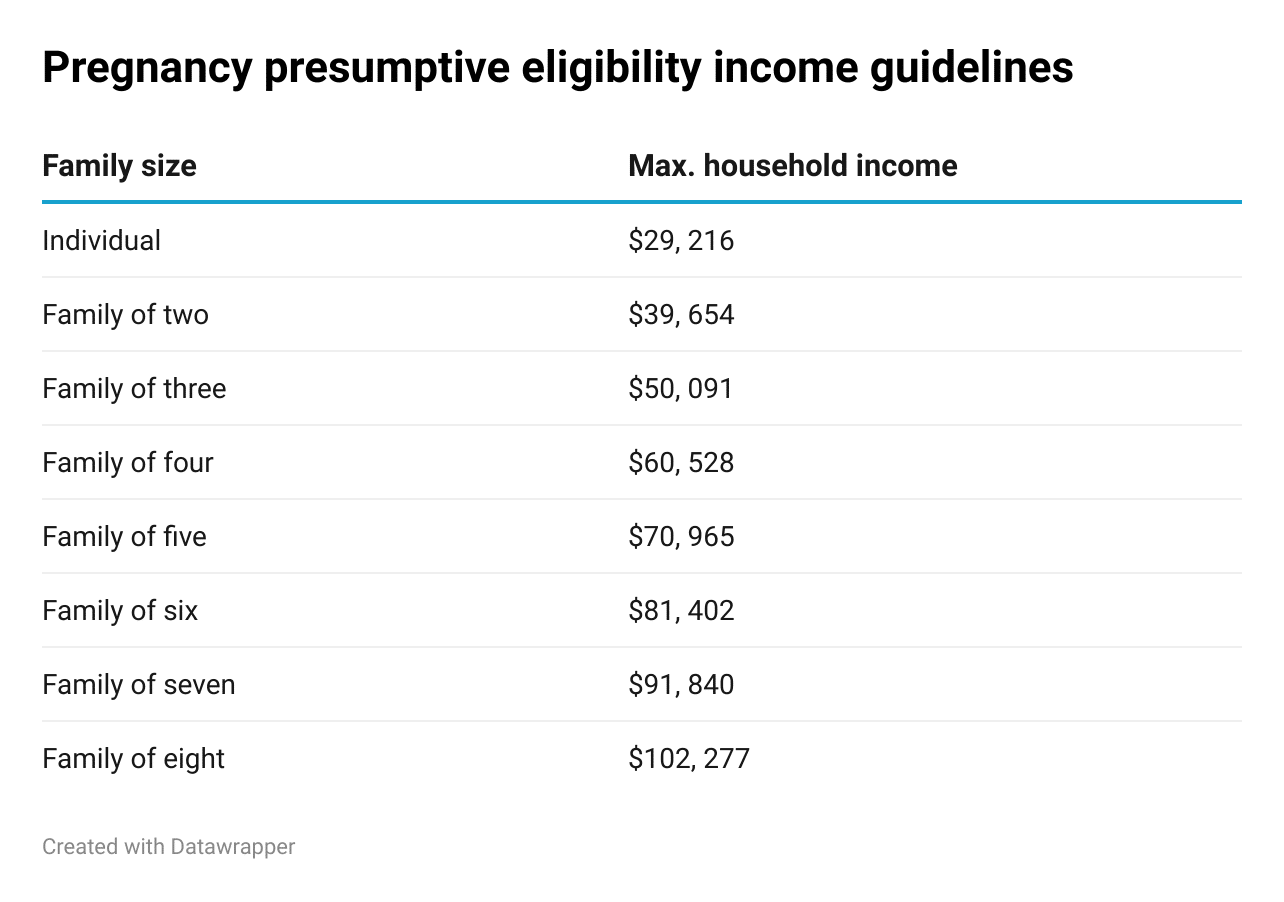

Doctors and other qualifying providers must complete an application and undergo eligibility determination training, in addition to submitting a memorandum of understanding with the agency once approved. Then, a pregnant woman whose income falls below 194% of the federal poverty level – about $29,000 annually for an individual – can bring proof of income to the doctor and, if approved, receive prenatal care the same day.

Westerfield said in an emailed statement in May that the agency would communicate to the public which locations are participating in the program, but said that they were “still working on what that outreach will look like.”

As of Tuesday, it is still unclear which, if any, providers are participating and whether Medicaid has sent any communication about the steps they must take if they want to participate.

“Medicaid clearly knows that the intent of the Legislature is for pregnant women to get in to see their doctor as early as possible, and they are working to stand up this program that is now the law,” said House Medicaid Chair and the bill's author Missy McGee, a Republican from Hattiesburg. “As the author of this legislation, I will be closely monitoring the rollout of this new program and am optimistic that it will be done in a timely manner.”

The Legislature made the bill broad enough that the Division of Medicaid would have the freedom to implement it in whatever way it saw fit, McGee explained.

“ … The Legislature's job is to create the policy. Now that it is law, it is Medicaid's job to implement it.”

Mississippi Today reached out to University of Mississippi Medical Center – Mississippi's largest Medicaid provider – to determine what, if any, communication it has received about how presumptive eligibility will work.

“We are still checking into the process for this, but don't have any comment at this time,” a hospital spokesperson told Mississippi Today on Tuesday.

In March, the number of Mississippi Medicaid applications that took more than 45 days to be processed was 29%, according to data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, due to “unwinding.” State Medicaid divisions across the country began reviewing their rolls last year for the first time in three years after the end of COVID-19 restrictions that prevented them from unenrolling beneficiaries, and Mississippi at times had a significant application backlog.

Without presumptive eligibility, pregnant women are forced to pay out of pocket or go without care in this interim period. Early prenatal care has been proven to mitigate a number of pregnancy-related problems including hypertension – the leading cause of maternal mortality in Mississippi and across the country – and preterm births, in which Mississippi leads the nation.

The state received more than $2 million of federal funds and an additional $602,000 in state money to implement the program, according to the 2024 Medicaid appropriation bill.

Advocates of the policy have said the program pays for itself when compared to how much it costs the state to care for one infant's prolonged stay in a neonatal intensive care unit, which can easily top $1 million, according to a study published in the American Medical Association Journal of Ethics.

How to know if you qualify

Anyone who is pregnant and makes at or below 194% of the federal poverty level qualifies for Medicaid and for presumptive eligibility. These individuals can start receiving care a soon as they find out they're pregnant by showing proof of monthly income to a doctor at a qualifying location.

While it's not known which providers, if any, have chosen to participate so far, Mississippi Today will continue to monitor the Division of Medicaid's implementation of the policy and report on qualifying providers as they sign up.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=372033

Mississippi Today

Dau Mabil’s brother goes back to court to get independent autopsy started

The brother of Dau Mabil, the Jackson man whose body was recovered from the Pearl River three weeks after he disappeared, is asking a judge to enforce an order to allow an independent autopsy to proceed.

The state's autopsy, released late last month, determined death by drowning by unknown cause.

In a Monday court filing, Bul Mabil of Texas argues that his brother's widow, Karissa Bowley, is preventing the second autopsy by vetoing his choice of a qualified forensic pathologist, Dr. Matthias Okoye of Nebraska.

“This Court did not authorize Karissa Bowley to select or veto the pathologist to conduct the independent autopsy of Dau Garang Mabil,” Lisa Ross, Bul Mabil's attorney, wrote in the order.

The court set a requirement for the pathologist to be at least as qualified as pathologists who conduct autopsies for the State of Mississippi along with having certain degrees or certifications. Ross argues that Okoye meets the requirements set in the court order.

Okoye is director of the Nebraska Institute of Forensic Sciences, a nonprofit organization that operates the forensic pathologist division of the coroner's office for several counties in the state.

He has investigated and certified over 15,000 deaths as a deputy and chief medical examiner and a coroner's pathologist and has performed over 12,000 autopsies, according to his curriculum vitae included in court records.

Spencer Bowley wrote in a Sunday email that his sister disagrees with Bul Mabil's choice of Okoye, who Bowley noted was previously sued for providing false information in an autopsy report.

“Dau deserves nothing less than to have all answerable questions answered regarding his death,” he wrote. “We will continue seeking to agree on a pathologist to pursue truth, rather than any individual person or organization's agenda.”

More than a decade ago, a daycare provider sued Okoye, who authored the report used to charge her with felony child abuse for the death of a 6-week-old. The charges were later dropped.

Okoye ruled the infant died from homicide from blunt force trauma to the head and asphyxiation. Pathologists hired by the plaintiff found the infant's death was due to sudden infant death syndrome.

In 2014, the Nebraska Supreme Court ruled in the woman's malicious prosecution lawsuit by reversing the lower court's order to grant Okoye and his organization summary judgment, finding “differing reasonable inferences (that) could be drawn as to whether Okoye knowingly provided false or misleading information in his autopsy report.”

Another forensic pathologist offered by Bul Mabil is Dr. Frank Peretti of Arkansas, but Ross wrote in the filing that he declined to conduct the autopsy because of a potential conflict of interest.

Bowley has offered the names of four forensic pathologists, according to a Friday email from her attorney John David Sanford included in court records.

Okoye has also conducted an independent autopsy for at least one other Mississippi resident: Lee Demond Smith, who died in the Harrison County Jail, according to an affidavit contained in the court records. His ruling disagreed with the county pathologist's ruling.

As of Tuesday afternoon, a court hearing had not been scheduled to consider the motion.

The delay comes a week and a half after the Bowleys released the state's autopsy results.

That day, Ross began asking the Department of Public Safety's attorney if Mabil's body was ready to be released. She received confirmation about a week later.

As part of requirements for the autopsy, the court set a 30-day window for the autopsy to be conducted.

Now that Capitol Police have finished its investigation, Ross is asking the court to act so the autopsy can be done within 30 days of June 27, which is when she received confirmation.

In May, Bowley agreed to allow a second autopsy, and Hinds County Chancery Judge Dewayne Thomas wrote that it would be paid for at Bul Mabil's “direction and expense.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Federal judge blocks Mississippi online age verification law

A federal judge has issued an injunction halting a Mississippi law requiring online platforms to verify the ages of users.

Mississippi lawmakers, parroting measures passed by legislatures in several other states, passed House Bill 1126 this year, saying it would protect children from explicit online content. The law was set to take effect Monday, but the tech industry group NetChoice sued the state in June, claiming it would unconstitutionally limit adults' free speech and privacy.

U.S. District Judge Sul Ozerden granted NetChoice's request for a preliminary injunction halting the law while the case moves forward. He said the plaintiff's claim shows “a substantial likelihood of success on the merits of its claim” of the unconstitutionality of the law.

NetChoice is fighting similar laws in other states and has secured several similar injunctions.

“An unconstitutional law will protect no one,”Chris Marchese, director of the NetChoice Litigation Center, said in a statement. “We're pleased the court sided with the First Amendment and stopped Mississippi's law from censoring online speech, limiting access to lawful information and undermining user privacy and security as our case proceeds. We look forward to seeing the law struck down permanently.

“If HB 1126 ultimately takes effect, mandating age and identity verification for digital services will undermine privacy and stifle the free exchange of ideas. Mississippi also commandeers websites to censor broad categories of protected speech, blocking access to important educational resources. Mississippians have a First Amendment right to access lawful information online free from government censorship.”

The Mississippi law, authored by Rep. Jill Ford, R-Madison, is called the “Walker Montgomery Protecting Children Online Act,” named after a Mississippi teen who reportedly committed suicide after an overseas online predator threatened to blackmail him.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

-

Mississippi News6 days ago

Pearl under boil water notice due to E. coli

-

Our Mississippi Home6 days ago

Mississippi State’s UTC Staff Win Seven Emmy Awards

-

Mississippi Business6 days ago

Communities qualify for Welcome Home Mississippi recertification

-

Mississippi News6 days ago

Tropical wave has a 70 percent chance of developing, National Hurricane Center says

-

Our Mississippi Home6 days ago

Celebrating the 15th Season of Festival South

-

SuperTalk FM6 days ago

Move over 662, a new area code is coming to north Mississippi

-

Kaiser Health News6 days ago

Supreme Court Upends Purdue Pharma Opioid Settlement

-

Mississippi News6 days ago

Youth Court Judge says there is a dire need for foster homes – Home – WCBI TV