Mississippi Today

Traumatized by past abuse, these women say a Mississippi therapist added to their pain

Editor’s note: This story contains graphic sexual content regarding allegations of sexual abuse.

Two women have reported to Hattiesburg police that counselor Wade Wicht sexually abused them during counseling sessions, but he may never face criminal charges because it’s not against the law in Mississippi for counselors to have sexual contact with their clients.

Wicht has already admitted to having sex with two women he counseled, a violation of the ethical code that prompted the loss of his license before the State Board of Examiners for Licensed Professional Counselors, which oversees and licenses counselors.

Wicht and his lawyers did not respond to repeated requests for comments regarding the women seeking criminal charges against him and the specific allegations against him.

Hattiesburg Police Det. LaShaunda Buckhalter said she could not comment because the case is under investigation.

More than half the states consider sex between mental health professionals and their patients a crime. Last year, the Mississippi House passed a bill that would have made it a crime for therapists, clergy, doctors and nurses to have sexual contact with those they treat or counsel.

But the bill died in the Senate Judiciary B Committee after some senators questioned the need for a law. If something like this happens, the church can “fire that person, and you don’t let that behavior continue,” said Committee Chairman Joey Fillingane.

Brad Eubank, a pastor for First Baptist Church in Petal who serves on the Southern Baptist Convention’s sex abuse task force, said this should be more than a firing offense — it should be a crime.

Such a law can help prevent professionals from “exploiting their power and authority to gain access to a vulnerable person,” he said. “It happens with counselors and unfortunately some pastors. It’s got to be stopped.”

Eubank, a survivor himself of sexual abuse, said the sexual battery statute in Mississippi needs reform. Under the current law, sexual assault has to involve penetration, or any such assault is only a misdemeanor.

“You can grab a woman and touch all of her body,” he said, and it only carries up to a $500 fine and six months in jail. “You’ve got to rape somebody, or it’s a simple assault.”

Heather Evans, whose Pennsylvania counseling firm specializes in treating sexual abuse by clergy and counselors, said clients typically share their darkest experiences. If a counselor makes calculated attempts to have sexual contact with them, she said, “That is abuse … It is always with the person who holds the power to protect and not harm, to respect but not abuse.”

The American Counseling Association has long banned such relationships: “Sexual and/or romantic counselor-client interactions or relationships with current clients, their romantic partners, or their family members are prohibited for a period of five years following the last professional contact.”

The women said Wicht told them his pornography addiction started as a young teen after he was introduced to Playboy magazines at a friend’s home, and he later read the Kama Sutra, an ancient manuscript that gained popularity for its description of sexual positions.

Hattiesburg High School classmate Chami Kane recalled a time when Wicht told friends and fellow soccer players that he wanted them to see his favorite movie. He showed them “Deliverance,” which features a brutal rape scene.

Kane said Wicht did it to shock them, and they were indeed shocked.

Wicht went on to Belhaven College, where he graduated in 1997 with a degree in psychology. It was at that point that he married his first wife and moved to the St. Louis area. Two years later, he received a master’s in counseling from Covenant Theological Seminary there.

After graduating, Wicht started a job at a nearby mental health facility. It was there he shadowed a clinician named Ramona, who would become his second wife.

Ramona told Mississippi Todat that Wicht pursued her, told her that his marriage was dead and that he was getting a divorce — only for her to learn later that wasn’t true.

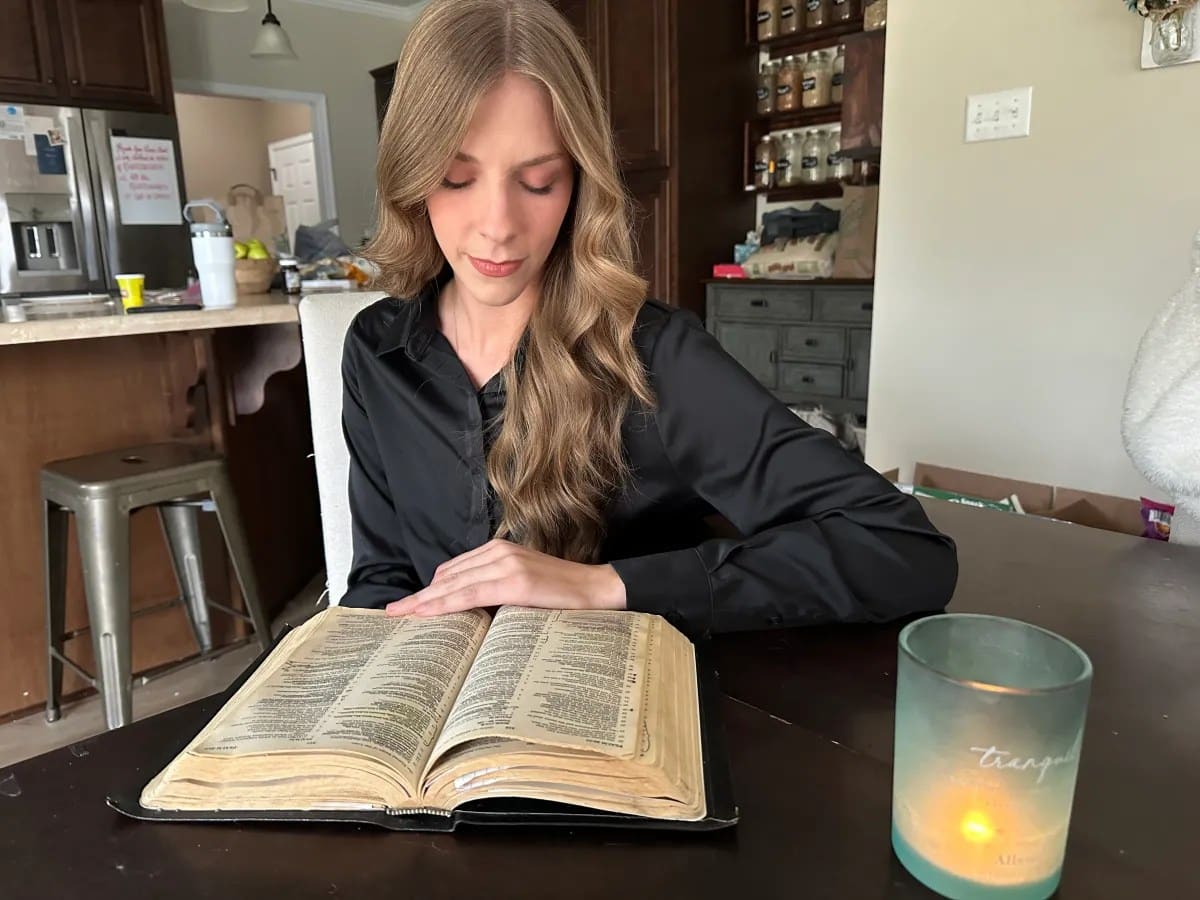

Three years later, the couple married. They remained in St. Louis and later moved to Hattiesburg, where Wicht’s roots run deep. The couple returned to the church his family had attended for generations, The First Presbyterian Church. Wicht became a deacon, and Ramona led a weekly Bible study group for women.

Wicht worked as a director at Pine Grove Behavioral and Addiction Services, which treats sex addiction. He was working there in 2010 when golfer Tiger Woods came for treatment.

Late one night, Ramona walked into the family room and discovered him watching porn, she said. “I hoped and prayed he no longer struggled with his former addictions. Looking back, it seems that working with sex addicts was fueling that flame.”

After leaving Pine Grove, Wicht ran a Louisiana company and then worked for Camellia Home Health and Hospice in Hattiesburg.

In 2015, he started a Christian counseling center, The Cornerstone Group, for mental health services in Hattiesburg with Ramona, who handled Cornerstone’s coaching as well as home-schooling their four children.

Shortly after Cornerstone opened, Wicht began a sexual relationship with a client, according to a counselors’ licensing board order.

Asked about this, Ramona said Wicht framed it to her as an angry husband had complained to the board and was going to sue “and take away everything you have.” She went into a “preserve my family mode,” she said. “I was a Christian woman, and I was going to fight for my marriage.”

Wicht never told his wife or his staff that his license previously expired. It wasn’t until 2018 that Wicht renewed his license.

Despite counseling for three years without a license, the board renewed his license without any fines or suspension.

LeeAnn Mordecai, executive director for the counselors’ licensing board, said the board’s orders are the only comments that she and the board can make about Wicht’s cases.

In 2019, Kimberly Cuellar, then 26, said she went to see the 44-year-old Wicht for help because of all the trauma she had suffered in a cult and an abusive relationship.

The sessions worsened her trauma, and she wound up writing a suicide note. She drank some wine to relax and “got very drunk instead, which definitely saved me,” she said.

She said she texted Wicht, who kept her on the phone for the next three hours instead of calling 911. “He spent the night in my house.”

In her next sessions with Wicht, they talked about treatment. “He’s very good at making you feel that he cares so much,” she said. “Even my own family had cut me off. I was desperate for somebody to care.”

As a Christian counselor, Wicht ended sessions in prayer. Each time, he scooted his chair closer, she said. “Then he put his hand on my leg.”

She said she told him she couldn’t afford all these sessions. He offered a trade: free counseling in exchange for her participation in research for a sex addiction book he was writing.

The next session, he asked her to lay on the floor, and after she did, he pulled down her pants and digitally penetrated her without her consent, claiming it was for his research, she told police.

“When you … started touching me, molesting me, I couldn’t believe it,” she wrote in text exchanges she shared with Mississippi Today. “It went on for so long. I could barely breathe.”

She wrote that she froze, just as she had during previous sexual trauma and spent the night on a park bench, where she was nearly kidnapped. Despite that, “I continued to trust you like an idiot.”

He pushed her to move to Hattiesburg, where she could receive intensive outpatient treatment. After arriving, a single mother with no support system, she suffered a panic attack, “memories of sexual abuse coming back to me,” she wrote. “But what did you do? After you found me balled up in the corner of the room, you used the opportunity to make sexual advances on me. To describe in detail what you wanted to do to me sexually, to help me to my bed and touch me again without asking. I froze again.”

In the next session, she said he continued the sexual touching, this time making her wear a blindfold. “He told me, ‘This is therapeutic to know what you like,’” she said. “Then it turned into, ‘I want to show you what real love is.’”

He became frustrated when she didn’t climax, she said. “I told him, ‘I feel very uncomfortable with this because I don’t have any connection with you.’”

He suggested they work on such a connection and that sex would help her heal, she said. “I was like a frog in the pot, slowly boiling.”

On May 21, 2021, the licensing board held a hearing on allegations from a client who said that Wicht had retaliated after she rejected him.

The woman, who asked not to be named for fear of retribution, told Mississippi Today that, in sessions spanning several years, she grew uncomfortable with Wicht’s “inappropriate” compliments on her looks and “creepy” hugs, including one where he held her tightly around her waist and wouldn’t let go.

The woman, who is also a licensed professional counselor, told Mississippi Today that Wicht originally told her that her husband was so dangerous that she needed to leave the state. But after she told him later that she wanted to see a different counselor, she said he retaliated by taking her husband’s side in a custody battle, raising questions about her “moral judgments and mood stability.”

In a letter, Wicht told the judge she suffered from “borderline personality traits” — a claim she said he never mentioned before, a claim her subsequent therapist called ludicrous.

During her discussion with the board, she questioned why Wicht was allowed to counsel her since he didn’t have a license when he started counseling her in 2016 or 2017. The board sided with Wicht.

“When the person you confided in and trusted with the pain and the abuse you and your children were living with turns around to make you look like the unfit parent,” she said, “you no longer trust anyone.”

She supports legislation to require videotaping in the mental health setting, she said. “It is so easy to manipulate clients because they are viewed as being mentally and emotionally inferior to the therapist.”

On Nov. 5, 2021, Belhaven College honored Wicht with an Alumni Award as a “servant leader entrepreneur who … demonstrates a commitment to ethical leadership in the marketplace.”

In his bio, he wrote that the Cornerstone Group provided “mental health services and is passionate about equipping others to live the life God intended.”

In 2022, the licensing board received complaints that alleged Wicht had sex with Cuellar and another woman who had been a client.

“What I did was wrong, and I disclosed this behavior to my wife just two weeks ago,” he wrote in a letter to the board. “I have also disclosed to my family, church, and counseling staff.”

Chami Kane, who grew up with Wicht and later worked as a counselor at Cornerstone, said Wicht felt like after he shared this, “Everybody should be OK. Now let’s all be friends again.”

She wrote him an email, which she shared with Mississippi Today, about something that had been bothering her. One day when she walked into the clinic, the front lights were off. When she saw Wicht, he led her into his wife’s office where he had been. There Kane said she saw a pair of his underwear on the desk, which he snatched up and stuffed into his pocket.

“You got on to me for not letting you know I was coming,” she wrote. “I know I almost caught you (with a client).”

He never responded to her email, she said. “I felt betrayed and angry and heartbroken. I also worried about his soul.”

In April 2022, Wicht wrote a letter, admitting to “moral failures and ethical violations in my personal and professional life.” In a June 9, 2022, order, the board gave him the ability to reapply for his license in a year.

He told the board that Kimberly Cuellar was a former client when he began to have sex with her and that he had simply failed to wait the required five-year period.

She said this wasn’t true and that he asked her to repeat this lie to the board. After he sexually abused her in sessions, he began to have sex with her in August 2019 during a trip to a Gulf Coast casino, she said. She shared an Aug. 21, 2019, photo of her with Wicht outside the casino as proof.

For the next several months, he continued to conduct therapy sessions with her, and he continued to have sex with her, she said.

Wicht told the board, his staff and his family that his relationship with Cuellar had ended, but she said it never stopped. In fact, she said he had told her that he was divorcing his wife to be with her.

When she discovered that was a lie, Cuellar said she packed up all she owned in a truck and left Hattiesburg for Louisiana.

Despite the distance, she said she remained under his spell. He made her report on all her therapy sessions and made her promise she wouldn’t tell the counselor about him, she said.

In her December 2022 session, she broke down and told her therapist about Wicht, she said. “She told me, ‘Oh, my gosh, you really need to leave.’ He made me fire her, and I did.”

By March 2023, she had repaired her family relationships, moved in with her mother and cut off her sexual relationship with Wicht, telling him that the only way they could have sex again would be if they were married.

Months later, he visited. That night at her mother’s home, she said she told him she was exhausted and going straight to sleep, only to wake up to “him on top of me.”

In text message exchanges, which she shared with Mississippi Today, she told him she felt “very violated” and “if I was awake, you know I would have not said yes to that.”

He responded, “Omgoodness, what??!! That is horrific!!! I am so incredibly sorry that’s how you experienced it. … What you’re accusing me of is criminal, Kimberly!”

“You moved my shorts, and you absolutely tried to get inside me,” she texted him.

“I touched you with my fingers, and I was touching myself,” he responded. “That’s what went on. I was NOT trying to have sex with you while you were sleeping.”

She told him “no” multiple times and, when he refused to stop, she grabbed him, she wrote. “Did you really stop? Not really. You then touched me without consent while you ejaculated on my body after all the no’s I had given. Attempted rape? Absolutely.”

Months later, she texted him, “I hear you’re claiming you’ve changed. … That’s interesting. I hope it’s true.”

He texted her back, “Thank you for reaching out and making a way for God to be glorified through repentance and reconciliation. … I’ve been praying for an opportunity to communicate with you again and started a letter as the first step in making full amends to you, Kimberly.”

The letter, she said, never arrived.

She had long made excuses for his behavior, but now he would be “exposed for the disgusting person you really are,” she texted him. “Do you need more stories? I have them. I have a lot of them.”

One time he spiked her drink, and “I woke up the next morning with only bits and pieces of my memory of the night,” she texted. “I asked you if you had done something to my drink, because I knew one drink would not have gotten me drunk, and you said you had, laughing it off. I was in pain, because you had done anal [sex] without consent.”

She texted him that he was “as bad or worse than every other man who has abused me. I came to you for help, and you used me for yourself. … I’m just letting you know now you didn’t win. I’m not yours, and I’ll never be yours.”

On Nov. 9, she drove to the Hattiesburg Police Department and told a detective what Wicht had done to her, and she is considering filing charges against him for attempted rape as well. “What I want is for him to be held responsible,” she said. “I don’t want this to happen to anyone ever again.”

Another woman also gave a statement to Hattiesburg police about what Wicht had done to her. Mississippi Today does not identify individuals alleging sexual assault or abuse unless they choose to do so.

In 2021, she and her then-husband went to see Wicht for marriage counseling. Instead of helping the couple draw closer, “He drove a wedge between us,” she said.

Her insurance didn’t cover the counseling, she said, and he offered to let her exchange a free membership to her family’s business. She agreed.

Her past made her an easy target, she said. She was a naïve 17-year-old when a teacher groomed her for months before sexually assaulting her, but her family didn’t want her to pursue charges, she said. “For 20 years, I literally wore a scarlet letter, blaming it on myself.”

To this day, she finds herself tying a shirt or jacket around her waist, she said. “I grew up Southern Baptist. God forbid you have a cute figure. There’s a lot of shame for sexual abuse victims.”

From the start, Wicht’s conversations steered to the sexual. After she mentioned her personal training, she said he talked about the size of her breasts and then asked her if she had implants.

She found such talk odd, but she presumed he knew best as a professional counselor, she said.

When she shared with Wicht the story of her sexual assault, she said he began to ask “very specific details of how it happened, which I thought was very strange. He even asked me if I bled.”

She said she found it difficult to share, and she joked that a drink would help her relax. The next thing she knew, she said, he had poured drinks for both of them — a habit he continued.

At the end of the session, Wicht asked for a hug, and she told him no, she said. He told her that being able to accept a hug was part of her healing, she said.

She finally began hugging him, she said.

Over time, she began to trust Wicht and rely on his advice on how she could improve her marriage. He seemed wise and professional. He listened well and spent more and more time with her.

The more time they spent together, the more she said she felt like he understood her. She felt like he really cared.

Months later, she said she told Wicht that she feared she was experiencing transference — that is, redirecting her feelings from her husband to Wicht. “I didn’t know what I needed to do.”

Instead of guiding her to another therapist, she said he reassured her that such transference “could be beneficial to the process.”

In the sessions that followed, she said he had her stand up and turn around, and he hugged her from behind. He told her that hugging like this was therapeutic.

Claiming he was helping her, he began putting his hand on her leg and telling her that she needed to learn to say no, she said. With each session, he moved his hand higher up her leg, she said. “He groomed the hell out of me. I can see it now. I couldn’t see it then.”

After having her talk about her sex life, she said he insisted to her that she was a sex addict and urged her to stop having sex with her husband.

His advice shocked her, she said, because she didn’t believe she was a sex addict. She rejected his talk that she needed to go somewhere to get treatment.

When he wasn’t satisfied that she was sharing all of the details on what she liked sexually, he urged her to masturbate so he could observe, she told police.

He had her stand up again, she told police. “He would hug me from behind while caressing my breasts and body. This progressed to him putting his hands inside my pants.”

He preyed on her, only to end their sessions in prayer, she said. “I finally got the courage to tell him to stop. I thought it was especially twisted for him to pray considering what he was doing.”

After sickness in her family and her own health struggles, she felt emotionally spent. “I was especially low,” she told police. “I was crying uncontrollably.”

She called Wicht for help, and he asked her to come into the office.

In past sessions, he had asked her to remove her clothes, she said. She had refused each time.

This time, she broke down and gave in to his demands. “I cried the whole time,” she said. “That’s the control that counselors have over your psyche and emotions.”

He put a blindfold on her, made her lie on her stomach and spread her bottom cheeks, and “he proceeded to penetrate me with his fingers,” she told police.

When he finished, “He held me and acted as if it had been a caring moment,” she told police. “That was the last time he touched me.”

Throughout his abuse, she told police, “He would remind me I could never in my life breathe a word of it. Said someone could die or be killed if I did. This was triggering as my abuser from teen years threatened to kill himself if I told anyone.”

What he did to her so traumatized her that thoughts of self-harm flooded her mind, she said. To combat this, she posted the suicide prevention hotline number on her wall and turned her closet into a prayer “war room,” where she sometimes slept.

To recover from this devastation, she paid $20,000 to be part of a therapeutic program out of Canada, she said. “I was afraid to go anywhere in the U.S. because I knew they would have to report it.”

She said she was so emotionally devastated at the time that it is only now, after her healing has begun, that she feels able to pursue possible criminal charges, despite the lack of a Mississippi law dealing with counselors.

It’s bad enough for a trusted person to exploit you, but when it’s a counselor, who knows so many intimate details about your life, “It rapes every part of your soul and mind,” she said. “It gets every piece of you.”

Nothing happened to the teacher who abused her as a teen, and he went on to sexually assault other girls, she said. She wants to make sure the same thing doesn’t happen with Wicht, she said, because “sexual abuse victims have had their voices taken.”

In April 2022, Wicht’s wife, Ramona, learned that “my husband of 20 years had been living a double life,” she told the pastors and elders of First Presbyterian Church, where is no longer a deacon. (Church officials declined to discuss the matter.)

Their marriage crumbled as she “uncovered layers of lies and betrayals,” she wrote. When she made him open the family safe, she expected to see stacks of cash. Instead, she saw dozens of sex toys and condoms, she said, and she had previously spotted a box with a blowup sex doll.

A letter she received from an accountant, which she shared with Mississippi Today, detailed how Wicht hadn’t completed personal or business taxes with the firm for seven years, and she wrote how he had also failed to pay employees, cut corners and done “the bare minimum for others while indulging himself.”

She was just discovering some of his reckless spending, including more than $21,000 he had spent on a single video game, she wrote.

Wicht isn’t being required to pay child support though she is the one 90% of the time caring for their four children (one of whom has special needs) and paying all the bills, she wrote. He has visitation rights, and the judge has yet to make a final decision on custody.

“I can’t even make ends meet on a monthly basis,” Ramona wrote. “We currently live in a dilapidated home while Wade enjoys a $2,400-a-month rental home. To make matters worse, I have been required to pay over $10,000 for counseling sessions to help Wade’s failing relationships with the children.”

She told Mississippi Today that she’s “deeply grieved by the sin I’ve seen, but I am grateful for the other victims who, like me, have finally found their voices. Moving forward, my prayer is for redemption, restoration and swift justice in the midst of this heartbreaking situation.”

Where to turn if you need help

Experts say if you or someone you know has been emotionally or sexually abused in therapy sessions, you need to seek help.

They recommend victims and survivors of sexual abuse seek therapy from a trusted and highly recommended expert in such healing as well as the advice of a lawyer before making any legal decisions.

The book “Psychotherapists’ Sexual Involvement with Clients” cites these as possible options:

- File a lawsuit for damages

- File a licensure complaint

- File a criminal charge

- File a complaint with a professional association

- Notify the employer, agency director, or church hierarchy (n the case of clergy practicing psychotherapy)

- Report to county or state authorities

- Seek therapy

To make contact with other victims and survivors:

MStherapistabuse@yahoo.com

For more information and a directory of additional resources, see: http://kspope.com/dual/index.php

Source: TELL (Therapy Exploitation Link Line)

To make contact with other victims and survivors:

MStherapistabuse@yahoo.com

For more information and a directory of additional resources, see: http://kspope.com/dual/index.php

Source: TELL (Therapy Exploitation Link Line)

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

Early voting proposal killed on last day of Mississippi legislative session

Mississippi will remain one of only three states without no-excuse early voting or no-excuse absentee voting.

Senate leaders, on the last day of their regular 2025 session, decided not to send a bill to Gov. Tate Reeves that would have expanded pre-Election Day voting options. The governor has been vocally opposed to early voting in Mississippi, and would likely have vetoed the measure.

The House and Senate this week overwhelmingly voted for legislation that established a watered-down version of early voting. The proposal would have required voters to go to a circuit clerk’s office and verify their identity with a photo ID.

The proposal also listed broad excuses that would have allowed many voters an opportunity to cast early ballots.

The measure passed the House unanimously and the Senate approved it 42-7. However, Sen. Jeff Tate, a Republican from Meridian who strongly opposes early voting, held the bill on a procedural motion.

Senate Elections Chairman Jeremy England chose not to dispose of Tate’s motion on Thursday morning, the last day the Senate was in session. This killed the bill and prevented it from going to the governor.

England, a Republican from Vancleave, told reporters he decided to kill the legislation because he believed some of its language needed tweaking.

The other reality is that Republican Gov. Tate Reeves strongly opposes early voting proposals and even attacked England on social media for advancing the proposal out of the Senate chamber.

England said he received word “through some sources” that Reeves would veto the measure.

“I’m not done working on it, though,” England said.

Although Mississippi does not have no-excuse early voting or no-excuse absentee voting, it does have absentee voting.

To vote by absentee, a voter must meet one of around a dozen legal excuses, such as temporarily living outside of their county or being over 65. Mississippi law doesn’t allow people to vote by absentee purely out of convenience or choice.

Several conservative states, such as Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas and Florida, have an in-person early voting system. The Republican National Committee in 2023 urged Republican voters to cast an early ballot in states that have early voting procedures.

Yet some Republican leaders in Mississippi have ardently opposed early voting legislation over concerns that it undermines election security.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

.

Mississippi Today

Mississippi Legislature approves DEI ban after heated debate

Mississippi lawmakers have reached an agreement to ban diversity, equity and inclusion programs and a list of “divisive concepts” from public schools across the state education system, following the lead of numerous other Republican-controlled states and President Donald Trump’s administration.

House and Senate lawmakers approved a compromise bill in votes on Tuesday and Wednesday. It will likely head to Republican Gov. Tate Reeves for his signature after it clears a procedural motion.

The agreement between the Republican-dominated chambers followed hours of heated debate in which Democrats, almost all of whom are Black, excoriated the legislation as a setback in the long struggle to make Mississippi a fairer place for minorities. They also said the bill could bog universities down with costly legal fights and erode academic freedom.

Democratic Rep. Bryant Clark, who seldom addresses the entire House chamber from the podium during debates, rose to speak out against the bill on Tuesday. He is the son of the late Robert Clark, the first Black Mississippian elected to the state Legislature since the 1800s and the first Black Mississippian to serve as speaker pro tempore and preside over the House chamber since Reconstruction.

“We are better than this, and all of you know that we don’t need this with Mississippi history,” Clark said. “We should be the ones that say, ‘listen, we may be from Mississippi, we may have a dark past, but you know what, we’re going to be the first to stand up this time and say there is nothing wrong with DEI.'”

Legislative Republicans argued that the measure — which will apply to all public schools from the K-12 level through universities — will elevate merit in education and remove a list of so-called “divisive concepts” from academic settings. More broadly, conservative critics of DEI say the programs divide people into categories of victims and oppressors and infuse left-wing ideology into campus life.

“We are a diverse state. Nowhere in here are we trying to wipe that out,” said Republican Sen. Tyler McCaughn, one of the bill’s authors. “We’re just trying to change the focus back to that of excellence.”

The House and Senate initially passed proposals that differed in who they would impact, what activities they would regulate and how they aim to reshape the inner workings of the state’s education system. Some House leaders wanted the bill to be “semi-vague” in its language and wanted to create a process for withholding state funds based on complaints that almost anyone could lodge. The Senate wanted to pair a DEI ban with a task force to study inefficiencies in the higher education system, a provision the upper chamber later agreed to scrap.

The concepts that will be rooted out from curricula include the idea that gender identity can be a “subjective sense of self, disconnected from biological reality.” The move reflects another effort to align with the Trump administration, which has declared via executive order that there are only two sexes.

The House and Senate disagreed on how to enforce the measure but ultimately settled on an agreement that would empower students, parents of minor students, faculty members and contractors to sue schools for violating the law.

People could only sue after they go through an internal campus review process and a 25-day period when schools could fix the alleged violation. Republican Rep. Joey Hood, one of the House negotiators, said that was a compromise between the chambers. The House wanted to make it possible for almost anyone to file lawsuits over the DEI ban, while Senate negotiators initially bristled at the idea of fast-tracking internal campus disputes to the legal system.

The House ultimately held firm in its position to create a private cause of action, or the right to sue, but it agreed to give schools the ability to conduct an investigative process and potentially resolve the alleged violation before letting people sue in chancery courts.

“You have to go through the administrative process,” said Republican Sen. Nicole Boyd, one of the bill’s lead authors. “Because the whole idea is that, if there is a violation, the school needs to cure the violation. That’s what the purpose is. It’s not to create litigation, it’s to cure violations.”

If people disagree with the findings from that process, they could also ask the attorney general’s office to sue on their behalf.

Under the new law, Mississippi could withhold state funds from schools that don’t comply. Schools would be required to compile reports on all complaints filed in response to the new law.

Trump promised in his 2024 campaign to eliminate DEI in the federal government. One of the first executive orders he signed did that. Some Mississippi lawmakers introduced bills in the 2024 session to restrict DEI, but the proposals never made it out of committee. With the national headwinds at their backs and several other laws in Republican-led states to use as models, Mississippi lawmakers made plans to introduce anti-DEI legislation.

The policy debate also unfolded amid the early stages of a potential Republican primary matchup in the 2027 governor’s race between State Auditor Shad White and Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann. White, who has been one of the state’s loudest advocates for banning DEI, had branded Hosemann in the months before the 2025 session “DEI Delbert,” claiming the Senate leader has stood in the way of DEI restrictions passing the Legislature.

During the first Senate floor debate over the chamber’s DEI legislation during this year’s legislative session, Hosemann seemed to be conscious of these political attacks. He walked over to staff members and asked how many people were watching the debate live on YouTube.

As the DEI debate cleared one of its final hurdles Wednesday afternoon, the House and Senate remained at loggerheads over the state budget amid Republican infighting. It appeared likely the Legislature would end its session Wednesday or Thursday without passing a $7 billion budget to fund state agencies, potentially threatening a government shutdown.

“It is my understanding that we don’t have a budget and will likely leave here without a budget. But this piece of legislation …which I don’t think remedies any of Mississippi’s issues, this has become one of the top priorities that we had to get done,” said Democratic Sen. Rod Hickman. “I just want to say, if we put that much work into everything else we did, Mississippi might be a much better place.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

House gives Senate 5 p.m. deadline to come to table, or legislative session ends with no state budget

The House on Wednesday attempted one final time to revive negotiations between it and the Senate over passing a state budget.

Otherwise, the two Republican-led chambers will likely end their session without funding government services for the next fiscal year and potentially jeopardize state agencies.

The House on Wednesday unanimously passed a measure to extend the legislative session and revive budget bills that had died on legislative deadlines last weekend.

House Speaker Jason White said he did not have any prior commitment that the Senate would agree to the proposal, but he wanted to extend one last offer to pass the budget. White, a Republican from West, said if he did not hear from the Senate by 5 p.m. on Wednesday, his chamber would end its regular session.

“The ball is in their court,” White said of the Senate. “Every indication has been that they would not agree to extend the deadlines for purposes of doing the budget. I don’t know why that is. We did it last year, and we’ve done it most years.”

But it did not appear likely Wednesday afternoon that the Senate would comply.

The Mississippi Legislature has not left Jackson without setting at least most of the state budget since 2009, when then Gov. Haley Barbour had to force them back to set one to avoid a government shutdown.

The House measure to extend the session is now before the Senate for consideration. To pass, it would require a two-thirds majority vote of senators. But that might prove impossible. Numerous senators on both sides of the aisle vowed to vote against extending the current session, and Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann who oversees the chamber said such an extension likely couldn’t pass.

Senate leadership seemed surprised at the news that the House passed the resolution to negotiate a budget, and several senators earlier on Wednesday made passing references to ending the session without passing a budget.

“We’ll look at it after it passes the full House,” Senate President Pro Tempore Dean Kirby said.

The House and Senate, each having a Republican supermajority, have fought over many issues since the legislative session began early January.

But the battle over a tax overhaul plan, including elimination of the state individual income tax, appeared to cause a major rift. Lawmakers did pass a tax overhaul, which the governor has signed into law, but Senate leaders cried foul over how it passed, with the House seizing on typos in the Senate’s proposal that accidentally resembled the House’s more aggressive elimination plan.

The Senate had urged caution in eliminating the income tax, and had economic growth triggers that would have likely phased in the elimination over many years. But the typos essentially negated the triggers, and the House and governor ran with it.

The two chambers have also recently fought over the budget. White said he communicated directly with Senate leaders that the House would stand firm on not passing a budget late in the session.

But Senate leaders said they had trouble getting the House to meet with them to haggle out the final budget.

On the normally scheduled “conference weekend” with a deadline to agree to a budget last Saturday, the House did not show, taking the weekend off. This angered Hosemann and the Senate. All the budget bills died, requiring a vote to extend the session, or the governor forcing them into a special session.

If the Legislature ends its regular session without adopting a budget, the only option to fund state agencies before their budgets expire on June 30 is for Gov. Tate Reeves to call lawmakers back into a special session later.

“There really isn’t any other option (than the governor calling a special session),” Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann previously said.

If Reeves calls a special session, he gets to set the Legislature’s agenda. A special session call gives an otherwise constitutionally weak Mississippi governor more power over the Legislature.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

-

Mississippi Today2 days ago

Mississippi Today2 days agoPharmacy benefit manager reform likely dead

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Virginia News Feed7 days agoYoungkin removes Ellis, appoints Cuccinelli to UVa board | Virginia

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed6 days agoTornado watch, severe thunderstorm warnings issued for Oklahoma

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days agoUniversity of Alabama student detained by ICE moved to Louisiana

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Georgia News Feed6 days agoGeorgia road project forcing homeowners out | FOX 5 News

-

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed7 days agoHometown Hero | Restaurant owner serves up hope

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days agoStrangers find lost family heirloom at Cocoa Beach

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed4 days agoTornado practically rips Bullitt County barn in half with man, several animals inside