Mississippi Today

Proposal to create Delta health authority draws fire from area’s lawmakers

A proposal to manage hospitals and clinics in the Delta under a new authority — and give political power over it to the governor — was met with distrust from the area’s lawmakers this week.

Representatives from the Delta Council, an economic development organization that was one of the first non-health care groups to endorse Medicaid expansion, presented a plan Tuesday at a joint meeting between the House and Senate Public Health Committees intended to help preserve health care in the Delta, one of the state’s sickest regions.

But the proposal was received poorly by Delta lawmakers, who said this was the first time they were hearing of it.

“I’m just so sick and tired,” said Rep. Otis Anthony, D-Indianola, as murmurs of support echoed around the table. “This is my sixth session, and I’m just sick and tired of people outside of the Delta telling us what we need, and we’re not at the table.”

The plan presented by the Delta Council centers on creating a Delta Rural Health Authority, which would manage a consortium of hospitals and health care facilities in the region, including rural medical clinics and federal qualified health centers.

The health care facilities would “collaborate” and share resources in order to expand physician coverage and services in the Delta.

The authority would also have the power to consolidate health care services in the Delta, if it deems appropriate.

Some of the objectives of the authority, the plan says, include maintaining essential health care services and workers in the Delta, maximizing financial outcomes and reimbursement opportunities for the region’s health care facilities and, subsequently, improving health outcomes.

The plan would not create new facilities or hospitals, and communities would not be forced to participate.

The Delta Council’s Wade Litton started the presentation Tuesday by emphasizing that the proposal is not a result of a few weeks of work — it’s been in the works for over 16 months, he said.

The council is asking for $5 million to $10 million from the Legislature to establish the authority.

Baker Donelson lawyer Richard Cowart told legislators that three to five hospitals in the Delta are already interested in being part of the authority, mentioning towns such as Greenville, Greenwood and Clarksdale. The presentation showed three hospitals under the authority — one a critical access hospital, one a rural emergency hospital and the last an acute care hospital.

“Until they know what it is, they’re not going to commit to it,” he said. “You have the Delta leadership, health care leaders saying we would like … to take a different approach and we would like your permission to do it.”

Gary Marchand, interim chief executive officer of Greenwood Leflore Hospital, confirmed that the facility is involved with the plan and said hospital leaders have discussed the proposal since late summer last year.

He wouldn’t comment on the proposal’s promise, aside from saying that the hospital’s leaders “agree with efforts to evaluate healthcare service delivery in the Delta.”

Clarksdale is home to Northwest Regional Medical Center. Delta Health System, which spent about $26 million on uncompensated care costs in 2022, is based in Greenville.

Cowart said the authority board would be composed of nine to 12 people. He said the governor would appoint three members, the Legislature would appoint two and then each community, as they joined, would appoint members.

But a draft of a Senate bill establishing the regional authority provided to Mississippi Today shows that the governor would appoint five members to the board. Though a majority would have to be Delta residents, the rest would just have to live in Mississippi.

That clause is the heart of the Democratic lawmakers’ concern regarding the health authority — the power that Gov. Tate Reeves would have over it.

More regional health authorities may be established under the draft bill with the governor’s approval, and the governor would appoint five members of those authority boards, too. And while the bill says board appointments will “seek to create a competencies-based board that also reflects the racial and ethnic diversity of the region,” Delta lawmakers say that language means that’s not guaranteed.

A senator has not formally introduced a bill in the Legislature. The lawmakers’ criticism of the proposal also largely stems from what they believe is a lack of community input.

“How do you have a solution when you haven’t had community meetings or a broad approach that includes legislators, boards of supervisors, hospital workers and administrators?” Rep. John Hines, D-Greenville, said in an interview. “They haven’t been that inclusive. It’s old men getting in a room doing what they want to do to keep the money for themselves.”

Hines made note of the Delta’s racial composition and the history of decisions made by white people in the South negatively affecting Black people.

“When you live as a Black person in a part of the state where Black people are the majority, they are most in danger when the state has more power over your life than people at the local level,” he said. “Whenever you take the voice of people away from them … you always end up making a community weaker.”

Though the Delta is a historically Black region, the council’s 2023-2024 officers appear to be eight white men.

The council’s representatives admitted at the meeting that though they had engaged with community members, county supervisors and hospital officials in the Delta, none of the area’s legislators had been contacted about the plan.

“Don’t you think it would have made sense to have involved people who were investing in these communities to come to the table rather than coming and saying, ‘This is what y’all need to do to survive,’” Hines said at the hearing. “I have some concerns about this. I’m not against a regional approach, but the proposal you presented I do not agree with.”

State Health Officer Dr. Daniel Edney, a Delta native, wouldn’t comment on the Delta representatives’ opposition to the plan but said the region is running out of health care options.

“This regionalization has proven itself, and the Delta doesn’t have many other options to look at,” he said, in an interview following the hearing. “Everybody knows that health care in the Delta needs help. If this isn’t it, what is it?”

Anthony, along with other representatives, said Medicaid expansion is a solution to the Delta’s dwindling health care infrastructure.

Despite support from the majority of Mississippians and extensive research underlining the policy’s financial and health benefits, Gov. Tate Reeves and other Republican leaders have vehemently opposed expansion. Reeves has instead pitched other ideas as alternatives. Rep. Darryl Porter, D-Summit, told Mississippi Today that he believes this authority is the governor’s latest attempt to “sidestep Medicaid expansion.”

Forty other states have adopted Medicaid expansion, and researchers say it would generate billions of dollars and thousands of jobs by insuring 200,000 to 300,000 Mississippians.

“These are conversations the governor has refused to have,” Anthony said at the hearing. “We can tell you from the Delta what the problem is.”

Nearly half of the state’s rural hospitals are at risk of closure, largely due to uncompensated care costs, or money hospitals spend taking care of uninsured patients.

“The governor wants local hospitals to fail,” said Rep. Jeffrey Harness, D-Fayette, in an interview with Mississippi Today.

The council’s plan does not take into account the impact of Medicaid expansion but Cowart noted that the policy would be “very beneficial” to the region, in addition to the proposal.

Anthony said he was “appalled” to hear recommendations from various organizations about the region’s health care crisis when stakeholders have been clear about the problem “for the past 30 years.”

“We’ve been telling this state what we need, and the state has consistently robbed and taken economic opportunity from the Delta,” he said. “It’s very disrespectful, when we starve the region economically by not making major economic investments in that area and then coming back and saying, ‘I know what’s wrong.’”

Reeves called two special legislative sessions in the past two weeks for lawmakers to spend hundreds of millions of tax dollars to lure businesses to areas outside of the Delta.

While almost the entire Capitol approved the economic deals, several Delta lawmakers previously told Mississippi Today they believe Reeves is using the power of his office to choose which areas of the state thrive and which starve from a lack of economic investment. The governor’s office has denied these allegations.

It’s not clear who would formally introduce the bill yet, or what its final iteration would be. But as it stands, Hines said he and his colleagues do not support the authority’s establishment.

“We are sick and tired of people telling us what to do rather than asking us what we need help with,” he said.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

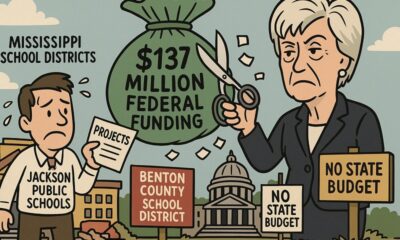

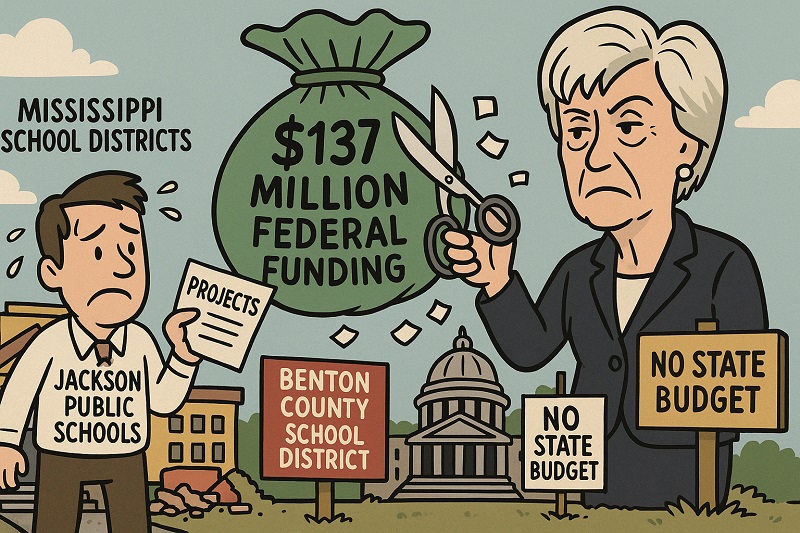

See how much your Mississippi school district stands to lose in Trump’s federal funding freeze

Mississippi school districts are grappling with the fallout of the Trump administration’s decision to freeze roughly $137 million in federal money and are hoping the U.S. Department of Education will reverse the decision.

Around 70 school districts were relying on the federal Department of Education’s decision under the Biden administration to allow them to spend federal pandemic grant money through next year.

But new U.S. Secretary of Education Linda McMahon notified state and local officials last month that the Trump administration was immediately cutting off the money.

Schools were already spending the money on a range of initiatives, including literacy and mathematics programs, mental health services, construction projects for outdated school facilities, and technology for rural districts.

“We’re really counting on all of our state and federal leaders to understand the predicament that we’re in as local school districts and do whatever it takes to get the federal government to honor this extension,” said Lawrence Hudson, the superintendent of Western Line School District in the Delta.

Hudson told Mississippi Today that his school district had already utilized federal money to renovate the heating and air systems in three old buildings in the district — two former Army barracks and a double-wide trailer — which had inferior ventilation.

The district also planned to use the money to improve ventilation in another building. However, it was unable to complete the project by the original deadline because it needed to take place during the summer break when the kids were not in the building.

Now those plans have been disrupted. Hudson said the district will have to find other money to pay for the project.

Lance Evans, the Mississippi Superintendent of Education, wrote a letter to McMahan saying the federal government failed to provide adequate notice that it would cut off access to money committed to schools during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the action has put school districts like Hudson’s in a bind.

Madi Biedermann, deputy assistant secretary for communications for the federal education department, told Mississippi Today in a statement that the COVID-19 pandemic is over and “school districts can no longer claim they are spending their emergency pandemic funds on ‘COVID relief.’”

“The Department will consider extensions on an individual project-specific basis where it can be demonstrated that funds are being used to directly mitigate the effects of COVID-19 on student learning,” Biedermann said.

Jackson Public School District, one of the largest districts in the state, has approximately $4.5 million in encumbered funds at risk due to the federal government’s decision, according to Earl Burke, the district’s Chief Operations Officer.

Of that amount, JPS had $3.6 million allocated for critical construction projects and just under $1 million designated for instructional support.

“That said, despite our best efforts, it is important to note that some construction projects may not be completed by the start of the school year due to this shift in funding availability,” Burke said.

The funding crunch also comes on the heels of Mississippi legislators voting to end their 2025 session without setting an annual budget.

Mississippi is one of the most federally dependent states in the nation, and the Trump administration, through its Department of Government Efficiency, has made slashing government spending one of its priorities.

Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann has said in recent interviews that legislative leaders might consider assisting state agencies that have been affected by federal funding cuts.

Whatever decisions federal and state leaders make, smaller school districts that received the federal money will be impacted.

The Benton County School District, located in rural northeast Mississippi, completed a heating and air conditioning project for one of its buildings, according to Superintendent Regina Biggers. The district paid for the project but was banking on the federal government reimbursing it around $166,000, something that may not now happen.

“This was a tremendous amount of money for a district our size,” Biggers said.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Crime lab sees increase in rape kits following new law

Twenty-seven percent more rape kits were sent to the state crime lab in 2024 than the year before in Mississippi.

The increase is thanks in part to a law passed in 2023 to streamline rape kit processing, which officials say resulted in more rape kits making it to the crime lab. However, because Mississippi has no complete rape kit inventory, it’s impossible to tell what impact it made on the backlog.

While variation from year to year is normal, the crime lab has not seen an influx that large in previous years – likely signifying the legislation’s effect, explained Commissioner Sean Tindell of the Department of Public Safety.

But Tindell added that he could not say how many kits, if any, are still getting stalled along the way.

House Bill 485 mandated law enforcement pick up rape kits from hospitals within 24 hours of being contacted, and that they transport the kits to the forensic lab within seven calendar days. It also created a sexual assault task force, whose members designed a system for survivors to track their rape kit as it changes hands.

The tracking system went into operation September 2024, Tindell said. Any rape victim who had a kit done after then can track the status of the kit by putting its serial number into the online system.

The idea was that rape kits could would no longer sit indefinitely in hospital refrigerators or in the trunks of cop cars, and that survivors would be kept in the know – the way patients are for any other hospital procedure.

“They leave the hospital and they don’t know where their kit is, they never hear anything. Can you imagine getting a cancer test and nobody ever calls you back to tell you what it was? For months or years or ever?” asked Ilse Knecht, policy director at End the Backlog, an organization seeking justice for sexual assault survivors through policy work around rape kits.

Backlogged rape kits have long been problem across the U.S. – one that first sparked public outcry in 1999 when it was discovered that New York City was sitting on 17,000 untested rape kits.

“What happened later was that the mayor decided to test them all, which was a years-long process, and there were very important and interesting cases that came out of that,” explained Knecht. “And it started to catch on, the other states started to look at what they had. And we started to get a sense of what was going on across the country.”

The root of the problem isn’t as simple as underfunded crime labs or a lack of resources in law enforcement agencies, Knecht said. It’s also a matter of culture, with some kits never being tested because victims aren’t believed.

“If they’re not the perfect victim, the case is going to be closed before it’s even opened.”

The Mississippi Prosecutors’ Association did not respond to a request for comment on whether the increase in submissions to the crime lab has led to an increase in prosecutions.

Knecht, who has 25 years of experience working in this area, joined End the Backlog in 2015, when she helped develop the group’s policy directives. After collaborating with dozens of sexual assault survivors and various professionals handling rape kits, her team came up with six pillars intended to guide states toward policies to enact meaningful and feasible change.

Mississippi’s 2023 legislation led to the adoption of three of the six pillars End the Backlog recommends: mandating the timely testing of all new kits; implementing mechanisms for survivors to easily find out about the status of their kits; and creating a tracking system for victims.

The other three pillars, which Mississippi does not have, are: implementing an annual statewide inventory of kits; mandating submission and testing of all backlogged kits; and allocating funding to submit, test and track kits.

The timeline the 2023 legislation imposed on law enforcement is more than reasonable, according to Ken Winter, executive director of the Mississippi Association of Chiefs of Police.

“It absolutely has not taken more staff or resources,” Winter said. “The only thing it’s taking is somebody paying attention to the process and making sure the evidence is handled in a timely manner – and they should be doing that anyways.”

House Bill 485 was a bipartisan effort led by Rep. Angela Cockerham, I-Magnolia, and co-authored by Reps. Dana McLean, R-Columbus; Jill Ford, R-Madison; and Otis Anthony, D-Indianola.

McLean said she believed the legislation was the first step to getting justice for sexual assault survivors.

But she later became aware that some rape victims have trouble earlier in the process – getting a rape kit done in the first place. McLean fought to change that this past session, and successfully oversaw the passage of a bill requiring hospitals to stock and perform rape kits.

What makes the problem still more complicated in Mississippi – and four other states – is that the state has not mandated an inventory of rape kits. There is no way to tell the extent of Mississippi’s backlog – or at what point in the process the kits are getting backlogged.

McLean said she hopes to make a mandatory statewide inventory her focus next legislative session.

The issue is dimensional, said Knecht. But the message of the movement is simple: to tell survivors that what they did by receiving a rape kit mattered.

“All of this was created to keep a promise to survivors,” Knecht said. “And to society because guess what – these kits represent dangerous people on the street. And when they’re not tested, we have 100 pages of stories of crimes that maybe could have been prevented if a rape kit had just been tested.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

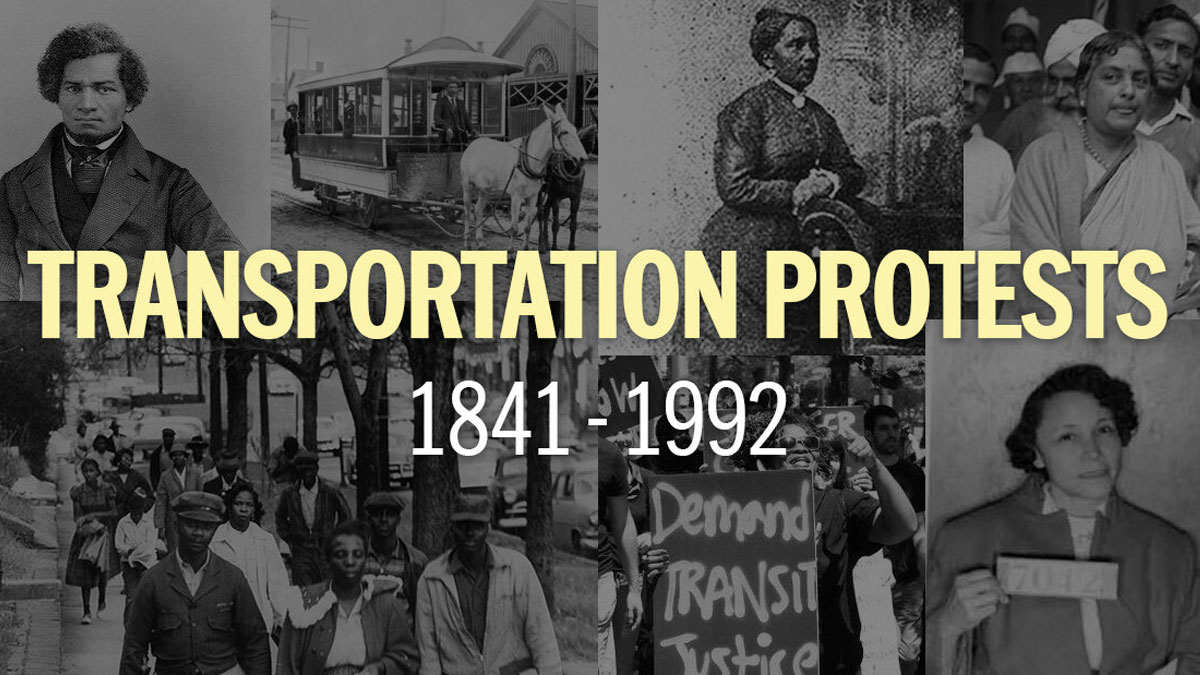

1863: Charlotte Brown refused to leave whites-only streetcar

April 17, 1863

As darkness fell on San Francisco, a young Black woman named Charlotte Brown walked a block from her home on Filbert Street and took a seat on the “whites-only” horse-drawn streetcar.

She and her family had moved to California from Maryland, a part of the city’s burgeoning Black middle class. Her father, James E. Brown, was an anti-slavery crusader and was a partner in the Black newspaper, Mirror of the Times.

When the conductor came to collect tickets, she handed him the ticket she had purchased, only for him to refuse to take it.

“He replied that colored persons were not allowed to ride,” she later testified. “I told him I had been in the habit of riding ever since the cars had been running. I answered that I had a great ways to go and I was later than I ought to be.”

The conductor asked her several times to leave. Each time she refused. When a white woman objected to her presence, the conductor grabbed her by the arm and forced her off the streetcar. She boarded twice more with the same result and sued.

Two years later, a jury awarded her the huge sum in her day of $500 (streetcar tickets were just 5 cents), and a judge ruled that barring passengers on the basis of race was illegal. He wrote in his ruling that he had no desire to “perpetuate a relic of barbarism.”

Her victories paved the way for the official end of racial discrimination on streetcars in San Francisco and beyond.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days agoMeasles cases confirmed in Arkansas children after travel exposure

-

Mississippi Today7 days ago

Mississippi Today7 days agoA self-proclaimed ‘loose electron’ journeys through Jackson’s political class

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days agoImpacts of Overdraft Fees | April 11, 2025 | News 19 at 10 p.m.

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Georgia News Feed6 days ago1-on-1 with Gov. Kemp’s Senior Advisor | Full interview

-

Mississippi Today5 days ago

Mississippi Today5 days agoOn this day in 1873, La. courthouse scene of racial carnage

-

Mississippi Today7 days ago

Mississippi Today7 days agoVoters can help maintain city of progress in upcoming Jackson election

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed6 days agoMom and son targeted in carjackings, stolen cars crime spree

-

Local News6 days ago

Local News6 days agoAG Fitch and Children’s Advocacy Centers of Mississippi Announce Statewide Protocol for Child Abuse Response