Mississippi Today

Most charter schools see performance scores decline

Nearly every charter school saw its letter grade decline this school year, according to state test results that measure student performance.

Accountability grades are based on state test results and other metrics, given on an A-F scale. Of the seven charter schools that received grades this year, one got a grade for the first time. For three more, this was their second year in the accountability system.

Charter schools are free public schools that do not report to a school board like traditional public schools. Instead, they are governed by the Mississippi Charter School Authorizer Board. They have more flexibility for teachers and administrators when it comes to student instruction and are funded by local school districts based on enrollment. Charter schools can more easily apply to open in a D or F rated district under the premise they will provide another option to students in struggling public schools.

RePublic Schools, which operates Smilow Collegiate, Smilow Prep, and Reimagine Prep in Jackson, saw the biggest declines from their 2022 performance. In a statement, the school network said it holds itself accountable for its performance and is reviewing the data to make changes in instructional practice. It also added that these scores are not representative of the schools’ dedication to their students.

Angela Bass, executive director of the Jackson RePublic Schools, declined to elaborate further.

Leflore Legacy Executive Director Tamala Boyd Shaw said the school’s F grade was “not what we had wanted.”

The sixth through eighth grade school in the Mississippi Delta had students take the science assessment for the first time this year, something Shaw said contributed to the decline from the D they received last year. She also pointed to the fact that the sixth grade students often come to the school several years behind, and it only has one year to get them up to speed.

“We want to definitely meet the needs of all of our scholars, and we’ll just continue to make whatever significant shifts (are necessary) … so that we not only see growth in our scholars, but proficiency,” she said.

The Charter School Authorizer Board is digging into the data to identify the school’s needs and see how it can provide support to school leaders, according to its Executive Director Lisa Karmacharya.

“Of course, I think we’re disappointed that the scores are not better than they were, but we also are encouraged by the additional infusion of monies (federal pandemic relief money) and the support that I think can come from the charter association,” she said.

While Clarksdale Collegiate, a K-8 school in the Mississippi Delta, received the same letter grade as last year, it was the only charter school that saw its accountability point value increase. Its 2023 score was two points shy of the cutoff for a C.

“(We) definitely wanted to be higher than a D but (are) pleased to see that growth, especially when you add the amount of growth that our kids made in each of the subject areas around proficiency,” said Amanda Johnson, the school’s executive director.

Johnson attributed the school’s improved performance in part to an additional focus on literacy. She said they opened up the library two nights a week and spent additional time with third graders preparing for their reading test.

Rachel Canter, executive director of Mississippi First, an education policy organization that helped craft the state’s charter school law in 2013, said charter schools in Mississippi are primarily serving the state’s “most vulnerable” students. Canter characterized those students as more likely to need special education services and have issues with absenteeism.

“That means that (charter schools) are going to have a harder, longer climb to recovery than many of our other school districts and the children that they’re serving,” she said. “We know that charter schools signed up to do that job – it’s a job they committed to do, and they’ve got to do that job.”

Canter said that while the causes of the declines vary at each school, schools need to focus on moving kids all the way up to proficiency, not just out of the lowest-scoring groups. She also said several schools need to focus on addressing chronic absenteeism.

She doesn’t expect parent demand for charter schools to be immediately impacted by these results, largely because charter parents felt “left behind” by the public school system.

“Over time, parents are going to want to see how their child improved, but I don’t think that’s going to change overnight because I think the parents that have their children in charter schools recognize what challenges they're facing,” she said.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article...

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=305286

Mississippi Today

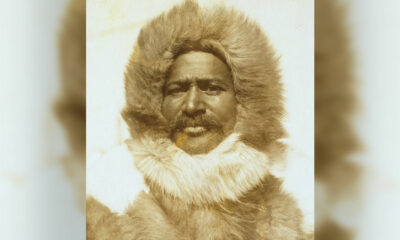

On this day in 1909, Matthew Henson reached the North Pole

April 6, 1909

Matthew Henson reached the North Pole, planting the American flag. Traveling with the Admiral Peary Expedition, Henson reportedly reached the North Pole almost 45 minutes before Peary and the rest of the men.

“As I stood there on top of the world and I thought of the hundreds of men who had lost their lives in the effort to reach it, I felt profoundly grateful that I had the honor of representing my race,” he said.

While some would later dispute whether the expedition had actually reached the North Pole, Henson’s journey seems no less amazing.

Born in Maryland to sharecropping parents who survived attacks by the KKK, he grew up working, becoming a cabin boy and sailing around the world.

After returning, he became a salesman at a clothing store in Washington, D.C., where he waited on a customer named Robert Peary. Pearywas so impressed with Henson and his tales of the sea that he hired him as his personal valet.

Henson joined Peary on a trip to Nicaragua. Impressed with Henson’s seamanship, Peary made Henson his “first man” on the expeditions that followed to the Arctic. When the expedition returned, Peary drew praise from the world while Henson’s contributions were ignored.

Over time, his work came to be recognized. In 1937, he became the first African-American life member of The Explorers Club. Seven years later, he received the Peary Polar Expedition Medal and was received at the White House by President Truman and later President Eisenhower.

“There can be no vision to the (person) the horizon of whose vision is limited by the bounds of self,” he said. “But the great things of the world, the great accomplishments of the world, have been achieved by (people with) … high ideals and … great visions. The path is not easy, the climb is rugged and hard, but the glory at the end is worthwhile.”

Henson died in 1955, and his body was re-interred with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery. The U.S. Postal Service featured him on a stamp, and the U.S. Navy named a Pathfinder class ship after him. In 2000, the National Geographic Society awarded him the Hubbard Medal.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

A win for press freedom: Judge dismisses Gov. Phil Bryant’s lawsuit against Mississippi Today

Madison County Circuit Court Judge Bradley Mills dismissed former Gov. Phil Bryant’s defamation lawsuit against Mississippi Today on Friday, ending a nearly two-year case that became a beacon in the fight for American press freedom.

For the past 22 months, we’ve vigorously defended our Pulitzer Prize-winning reporting and our characterizations of Bryant’s role in the Mississippi welfare scandal. We are grateful today that the court, after careful deliberation, dismissed the case.

The reporting speaks for itself. The truth speaks for itself.

This judgment is so much more than vindication for Mississippi Today — it’s a monumental victory for every single Mississippian. Journalism is a public good that all of us deserve and need. Too seldom does our state’s power structure offer taxpayers true government accountability, and Mississippians routinely learn about the actions of their public officials only because of journalism like ours. This reality is precisely why we launched our newsroom nine years ago, and it’s why we devoted so much energy and spent hundreds of thousands of dollars defending ourselves against this lawsuit. It was an existential threat to our organization that took time and resources away from our primary responsibilities — which is often the goal of these kinds of legal actions. But our fight was never just about us; it was about preserving the public’s sacred, constitutional right to critical information that journalists provide, just as our nation’s Founding Fathers intended.

Mississippi Today remains as committed as ever to deep investigative journalism and working to provide government accountability. We will never be afraid to reveal the actions of powerful leaders, even in the face of intimidation or the threat of litigation. And we will always stand up for Mississippians who deserve to know the truth, and our journalists will continue working to catalyze justice for people in this state who are otherwise cheated, overlooked, or ignored.

We appreciate your support, and we are honored to serve you with the high quality, public service journalism you’ve come to expect from Mississippi Today.

READ MORE: Judge Bradley Mills’ order dismissing the case

READ MORE: Mississippi Today’s brief in support of motion to dismiss

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Mississippi Today

Meet Willye B. White: A Mississippian we should all celebrate

In an interview years and years ago, the late Willye B. White told me in her warm, soothing Delta voice, “A dream without a plan is just a wish. As a young girl, I had a plan.”

She most definitely did have a plan. And she executed said plan, as we shall see.

And I know what many readers are thinking: “Who the heck was Willye B. White?” That, or: “Willye B. White, where have I heard that name before?”

Well, you might have driven an eight-mile, flat-as-a-pancake stretch of U.S. 49E, between Sidon and Greenwood, and seen the marker that says: “Willye B. White Memorial Highway.” Or you might have visited the Olympic Room at the Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame and seen where White was a five-time participant and two-time medalist in the Summer Olympics as a jumper and a sprinter.

If you don’t know who Willye B. White was, you should. Every Mississippian should. So pour yourself a cup of coffee or a glass of iced tea, follow along and prepare to be inspired.

Willye B. White was born on the last day of 1939 in Money, near Greenwood, and was raised by grandparents. As a child, she picked cotton to help feed her family. When she wasn’t picking cotton, she was running, really fast, and jumping, really high and really long distances.

She began competing in high school track and field meets at the age of 10. At age 11, she scored enough points in a high school meet to win the competition all by herself. At age 16, in 1956, she competed in the Summer Olympics at Melbourne, Australia.

Her plan then was simple. The Olympics, on the other side of the world, would take place in November. “I didn’t know much about the Olympics, but I knew that if I made the team and I went to the Olympics, I wouldn’t have to pick cotton that year. I was all for that.”

Just imagine. You are 16 years old, a high school sophomore, a poor Black girl. You are from Money, Mississippi, and you walk into the stadium at the Melbourne Cricket Grounds to compete before a crowd of more than 100,000 strangers nearly 10,000 miles from your home.

She competed in the long jump. She won the silver medal to become the first-ever American to win a medal in that event. And then she came home to segregated Mississippi, to little or no fanfare. This was the year after Emmett Till, a year younger than White, was brutally murdered just a short distance from where she lived.

“I used to sit in those cotton fields and watch the trains go by,” she once told an interviewer. “I knew they were going to some place different, some place into the hills and out of those cotton fields.”

Her grandfather had fought in France in World War I. “He told me about all the places he saw,” White said. “I always wanted to travel and see the places he talked about.”

Travel, she did. In the late 1950s there were two colleges that offered scholarships to young, Black female track and field athletes. One was Tuskegee in Alabama, the other was Tennessee State in Nashville. White chose Tennessee State, she said, “because it was the farthest away from those cotton fields.”

She was getting started on a track and field career that would take her, by her own count, to 150 different countries across the globe. She was the best female long jumper in the U.S. for two decades. She competed in Olympics in Melbourne, Rome, Tokyo, Mexico City and Munich. She would compete on more than 30 U.S. teams in international events. In 1999, Sports Illustrated named her one of the top 100 female athletes of the 20th century.

Chicago became White’s home for most of adulthood. This was long before Olympic athletes were rich, making millions in endorsements and appearance fees. She needed a job, so she became a nurse. Later on, she became an public health administrator as well as a coach. She created the Willye B. White Foundation to help needy children with health and after school care.

In 1982, at age 42, she returned to Mississippi to be inducted into the Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame and was welcomed back to a reception at the Governor’s Mansion by Gov. William Winter, who introduced her during induction ceremonies. Twenty-six years after she won the silver medal at Melbourne, she called being hosted and celebrated by the governor of her home state “the zenith of her career.”

Willye B. White died of pancreatic cancer in a Chicago hospital in 2007. While working on an obituary/column about her, I talked to the late, great Ralph Boston, the three-time Olympic long jump medalist from Laurel. They were Tennessee State and U.S. Olympic teammates. They shared a healthy respect from one another, and Boston clearly enjoyed talking about White.

At one point, Ralph asked me, “Did you know Willye B. had an even more famous high school classmate.”

No, I said, I did not.

“Ever heard of Morgan Freeman?” Ralph said, laughing.

Of course.

“I was with Morgan one time and I asked him if he ever ran track,” Ralph said, already chuckling about what would come next.

“Morgan said he did not run track in high school because he knew if he ran, he’d have to run against Willye B. White, and Morgan said he didn’t want to lose to a girl.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

-

Mississippi Today5 days ago

Mississippi Today5 days agoPharmacy benefit manager reform likely dead

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed6 days agoTornado practically rips Bullitt County barn in half with man, several animals inside

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago'I think everybody's concerned': Mercedes-Benz plant eyeing impact of imported vehicle tariffs

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed5 days agoFlorida special election results: GOP keeps 2 U.S. House seats in Florida

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago41st annual Bloomin Festival Arts and Crafts Fair (April 5 & 6) | March 31, 2025 | News 19 at 9 a.m.

-

News from the South - South Carolina News Feed3 days ago

News from the South - South Carolina News Feed3 days agoSouth Carolina clinic loses funding due to federal changes to DEI mandates

-

Mississippi Today5 days ago

Mississippi Today5 days agoRole reversal: Horhn celebrates commanding primary while his expected runoff challenger Mayor Lumumba’s party sours

-

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed5 days agoMother turns son's tragedy into mental health mission