Mississippi Today

Mississippi jailed more than 800 people awaiting psychiatric treatment in a year. Just one jail meets state standards.

This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with Mississippi Today. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

In Mississippi, many people awaiting court-ordered treatment for mental illness or substance abuse are jailed, even though they haven’t been charged with a crime. Read our full series here.

Fourteen years ago, Mississippi legislators passed a law requiring county jails to be certified by the state if they held people awaiting court-ordered psychiatric treatment.

Today, just one jail in the state is certified.

And yet, from July 2022 to June 2023, more than 800 people awaiting treatment were jailed throughout the state, almost all in uncertified facilities, according to state data.

Mississippi Today and ProPublica have been reporting on county officials’ practice of jailing people with mental illness, most of whom haven’t been charged with a crime, as they await treatment under the state’s civil commitment law. After the news organizations started asking about the 2009 law earlier this year, the state attorney general’s office concluded that it is a “mandatory requirement” that the Mississippi Department of Mental Health certify the facilities where people are held after judges have ordered them into treatment.

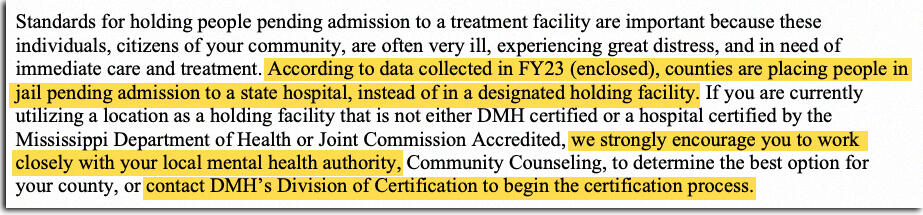

The Department of Mental Health, which oversees the state’s behavioral health system and has no other responsibility for jails, responded by sending letters to county officials across the state encouraging them to stop holding people in uncertified jails. But the law provides no funding to help counties comply and no penalties if they don’t.

Under state law, counties are responsible for housing people going through the commitment process until they are admitted to a state hospital. Counties are allowed to put them in jail before their court hearings if there’s “no reasonable alternative.”

The last time the Department of Mental Health tried to ensure those jails met state standards, more than a decade ago, it had little success. After the law passed, the agency got to work to inform counties about the new rules. Some didn’t respond. Others expressed interest but didn’t follow through. By 2013, just two jails had been certified. (One of them no longer is.) After that, the effort apparently petered out, according to a review of state documents.

To be certified, a jail must offer on-call crisis care by a physician or psychiatric nurse practitioner and must have a supply of medications. Staff must be trained in crisis intervention and suicide prevention. People detained during the commitment process must be housed separately from people charged with crimes, in rooms free of fixtures or structures that could be used for self-harm, according to Department of Mental Health standards that took effect in 2011.

“If they’re going to be held in jail, they have to receive some kind of treatment in a semi-safe environment,” a department attorney told The Clarion-Ledger at the time.

Until recently, many county officials weren’t even aware of those requirements, according to interviews across the state — even though they were routinely jailing people solely because they might need mental health treatment. Mississippi appears to be the only state in the country where people awaiting treatment are commonly jailed without charges for days or weeks at a time.

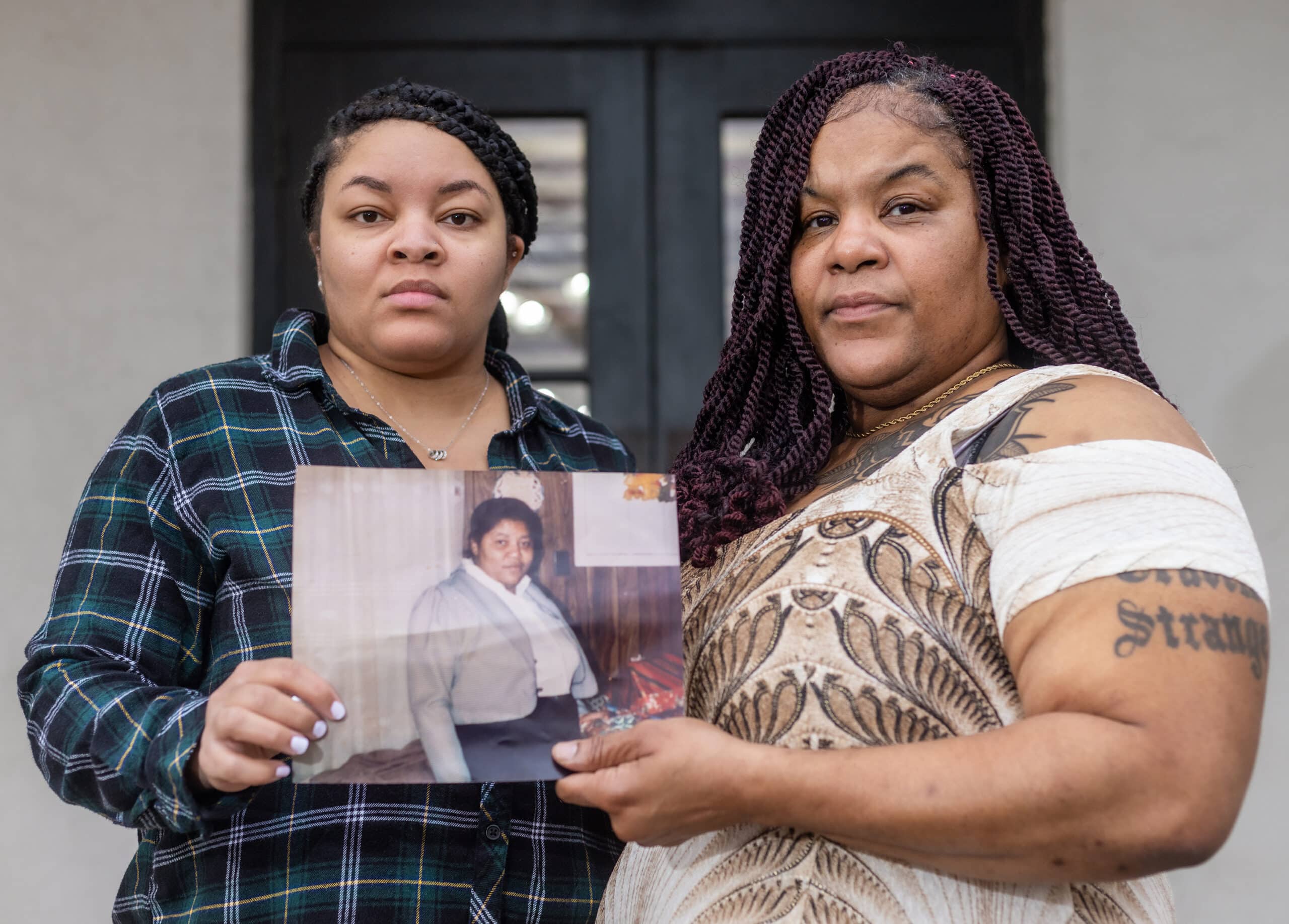

Mississippi jails are subject to no statewide health and safety standards. Many jails treat people going through the civil commitment process virtually the same as those who have been charged with crimes, Mississippi Today and ProPublica found. They’re shackled and given jail uniforms. They’re often held in the same cells as criminal defendants. They receive minimal medical care. Some said they couldn’t access prescribed psychiatric medications. Since 1987, at least 18 people going through the commitment process for mental illness and substance abuse have died after being jailed, most of them by suicide.

Some local officials say getting certified could be expensive. Sheriffs worry it could codify their role as their county’s de facto mental health care provider.

“It looks like the state wants the sheriff to be the chief mental health officer,” said Will Allen, attorney for the Mississippi Sheriffs’ Association. “This is coming down to the state stuffing the cost of this down to the counties, and frankly I just think that’s wrong.”

‘Are you going to shut the jail down? No.’

The genesis of the 2009 law was a conversation state Sen. Joey Fillingane had with his girlfriend at the time, a social worker who worked with troubled youth. She told him that Mississippians going through the commitment process in some counties were locked in jail cells like criminals, while in other counties they were held in hospitals like patients, according to a 2011 news story in The Clarion-Ledger.

Fillingane’s bill addressed that. “Shouldn’t there be some kind of minimum standard where you’re holding people who haven’t committed a crime?” the Republican from Sumrall, near Hattiesburg, said in that story about his legislation.

His bill passed with little fanfare. It made it “illegal for individuals committed to a DMH behavioral health program to be held in jail unless it had been certified” as a holding facility, an agency staffer wrote in a timeline of the law’s implementation obtained by Mississippi Today and ProPublica.

The board overseeing the Department of Mental Health set detailed standards for those facilities. Department staff surveyed counties to see whether they could meet them.

Ed LeGrand was head of the department when the law passed. He said he viewed it as a progressive effort that could spur counties to stop holding mentally ill people in jail. And even if that didn’t happen, the law would improve jail conditions — at least somewhat.

“I didn’t think that everybody would be able to meet those standards. I thought they would give it a try,” he said in a recent interview. “A lot of them did, but some of them didn’t.”

Department staff met with county officials and toured jails to offer assistance. Those visits, which records show mostly took place in 2011 and 2012, were the first time the Department of Mental Health had tried to get a comprehensive look at the local facilities where Mississippians awaited psychiatric treatment in state hospitals, LeGrand said.

Many jails were poorly equipped to care for these people, according to notes by agency staff.

“Toured the current jail (scary),” reads a status update written after staff visited Tishomingo County, in the northeast corner of the state, shortly before the county opened a new jail. In Jones County in south Mississippi, where the jail had 180 inmates and only four staff: “The holding cells are not safe for violent behavior. Too much cement.”

Jones County Sheriff Joe Berlin said the cells have not changed since then, though now detainees are monitored with cameras.

In early 2011, LeGrand told county officials who hadn’t already begun the certification process that they had six months to find a certified provider to house people awaiting treatment.

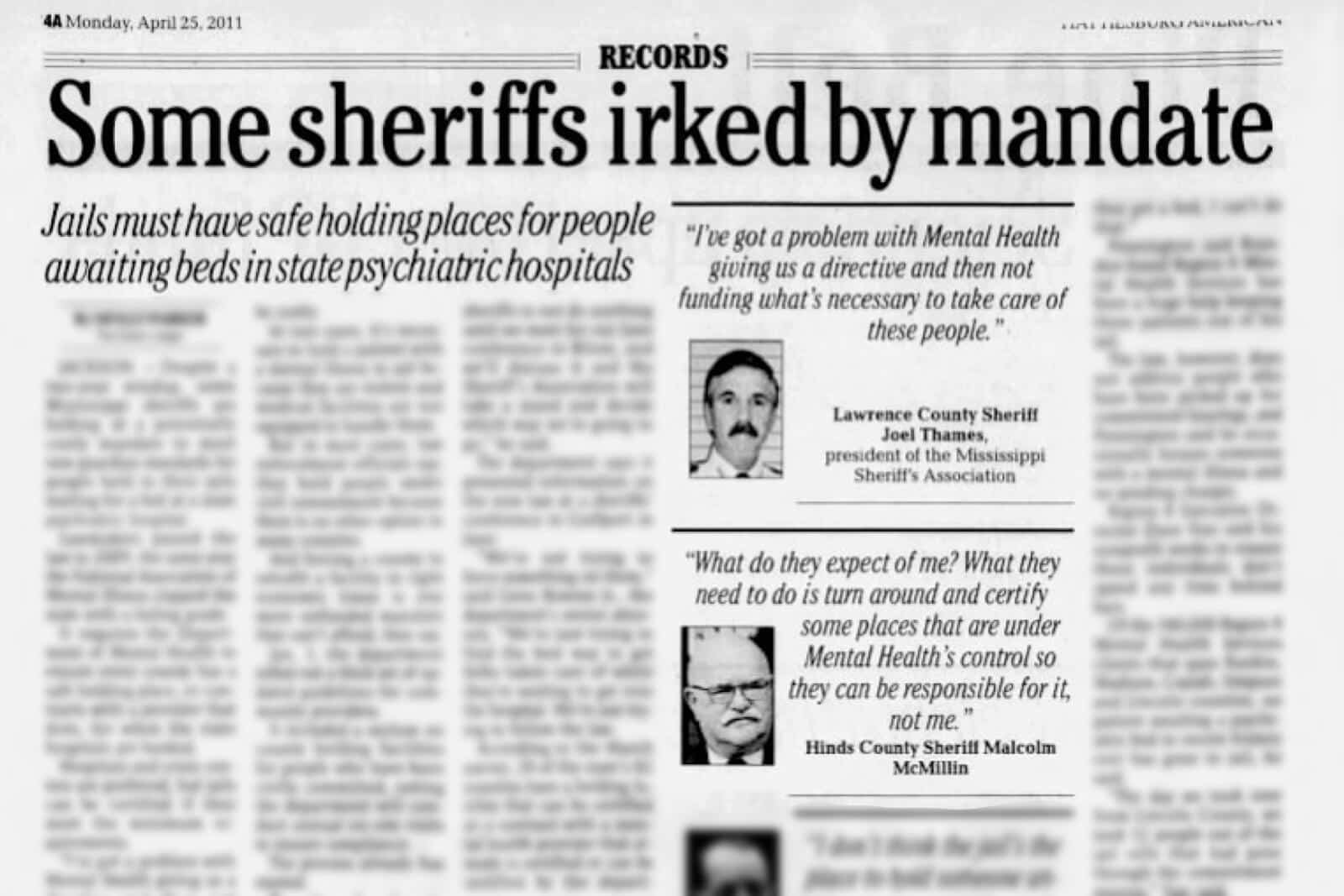

Sheriffs were frustrated. Some objected to being told they had to upgrade their jails and train guards so they could care for mentally ill people they didn’t think they should be responsible for in the first place.

“What do they expect of me?” one sheriff was quoted as saying in the 2011 news story. “What they need to do is turn around and certify some places that are under Mental Health’s control so they can be responsible for it, not me.”

Some county officials concluded there was little the state could do if they didn’t comply. Mike Harlin, the jail administrator in Lamar County, discussed the standards with a Department of Mental Health staffer in 2012, according to an agency memo. In an interview this year, Harlin said he remembered thinking, “What are you going to do? Are you going to shut the jail down? No.”

By June 2013, jails in just two of the state’s 82 counties had been certified, according to the department’s tally. (A hospital was certified in another county, and a different type of facility was certified in a fourth.)

Six counties said they couldn’t meet the standards. Another 23 had received guidance from the department on how to meet them. Thirty, including a few of the counties that had received advice, eventually said they didn’t jail people, some because they had contracts with providers. Twenty-one never responded.

Mississippi Today and ProPublica requested all Department of Mental Health records since 2010 related to enforcement of the certification law and correspondence with counties. Documents through 2013 included standards, correspondence, memos describing visits to county facilities and a log summarizing contact with each county. After that, the records released show no statewide outreach.

The final entry in the department’s timeline of the law’s implementation reads: “June 2013 was the last attempt to update the information about DMH Designated Mental Health Holding Facilities due to lack of additional responses from the counties.” That timeline is undated, but a department spokesperson said data in the file shows that it was created in January 2015 by a staffer who held positions in the certification and behavioral health divisions.

LeGrand, who served until 2014, said he doesn’t recall any decision to stop contacting counties about the law.

Katie Storr, the current chief of staff at the Department of Mental Health, told Mississippi Today and ProPublica it’s possible staff did communicate with counties beyond what the records indicate. “After more than a decade, a lack of correspondence, email, or other documentation is not indicative that communication and follow-ups did not take place,” she wrote in an email. However, she said the department had no additional records that would show this.

During this time, Storr wrote, the department was focused on trying to get counties to hold people going through the commitment process in short-term crisis stabilization units rather than jail.

Department can’t ‘boss counties around’

The recent effort to implement the certification law stems from inquiries by Mississippi Today and ProPublica.

In January, the news organizations asked the head of the Department of Mental Health, Wendy Bailey, if the department certifies jails where people are held as they await admission to a state hospital. Bailey, who handled communications for the department when the certification law passed, initially said it didn’t apply to jails. In March, after reviewing documents showing prior efforts to certify jails, she said she didn’t believe the law was intended to apply to them.

After our inquiries, Bailey sought an opinion from the attorney general. (Such opinions are not binding, but officials who request and abide by them are protected from liability.)

Around the same time, the Department of Mental Health contacted the four facilities it had previously certified to schedule inspections. The department’s standards say such inspections will happen annually, but this was the first year in which staff had sought to visit all of them since 2017. (Storr said the inspection effort was planned before inquiries by Mississippi Today and ProPublica.)

In March, staffers inspecting the Chickasaw County jail in rural northeastern Mississippi found serious violations. Inmates and people awaiting mental health treatment were housed together in the same cells, where beds were anchored with long bolts that “could be used by a person to harm themselves,” the reviewers recorded.

The department suspended the jail’s certification in August, but reinstated it after the county submitted a compliance plan that included shortening the bolts and providing mental health training for staff.

Lafayette County told the state it didn’t want its jail to be certified anymore. The certification for a holding facility in Warren County, home to Vicksburg, was suspended. A hospital in Alcorn County in northeast Mississippi maintained its certification.

In August, the attorney general’s office confirmed that the department must “ensure that each county holding facility, including but not limited to county jails,” meets its standards. If they don’t, an assistant attorney general wrote, the law allows the department to require counties to contract with a county that does have a certified facility.

When Bailey informed county officials about the opinion in her October letter, she instructed that if a county holds someone in an uncertified facility, including a jail, officials should contact the department to seek certification or work with local community mental health centers. These are publicly funded, independent providers set up to ensure that poor, uninsured people can access mental health care.

Several counties, including Lamar, have taken up the matter in public meetings or have contacted the department to begin the certification process.

Storr told Mississippi Today and ProPublica that the department asked counties to initiate the certification process because the law says it’s up to counties to determine which facility they use.

But the Department of Mental Health already knows which counties have held people in uncertified jails. Starting in July 2021, in response to a federal lawsuit over the state’s mental health system, department staff have tracked how many people come to state hospitals directly from jails for psychiatric treatment.

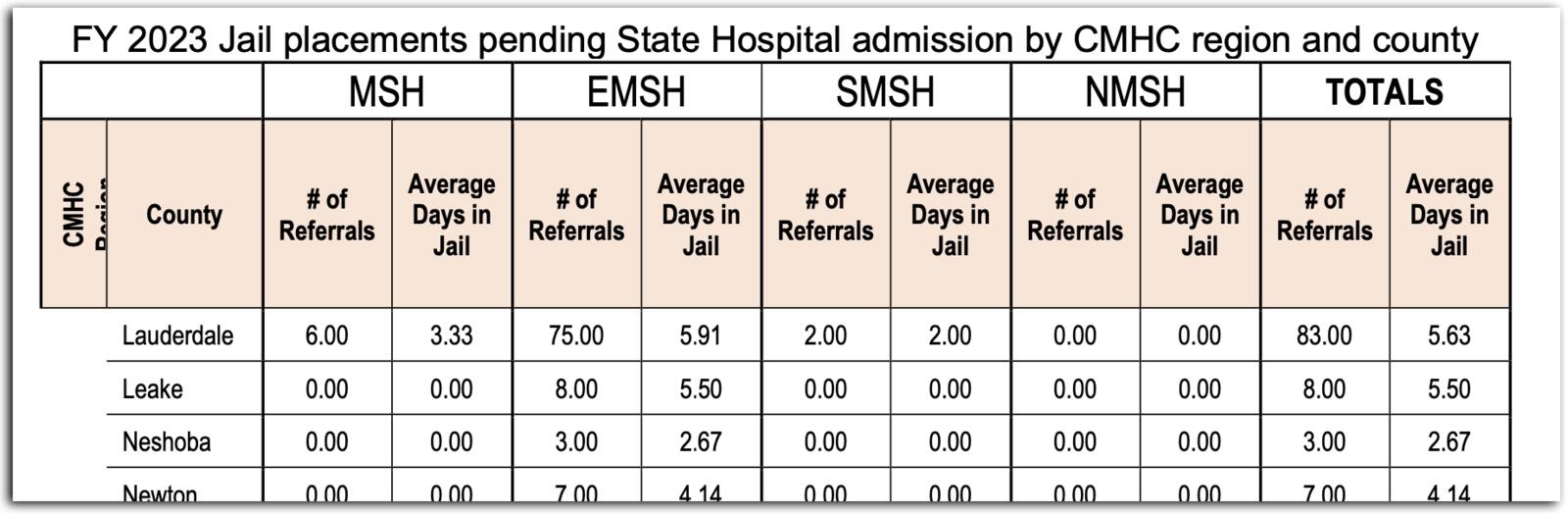

The tally for the year ending in June breaks down all 71 jails, only one of which is certified, where a total of 812 people who had been civilly committed were held before being admitted to a state hospital. (The tally doesn’t include anyone who was jailed and released without being admitted to a state hospital.)

In Lauderdale County, on the Alabama line: 83. Across the state in DeSoto County: 76. A couple hundred miles down the Mississippi River in Adams County: 33.

Storr and Bailey have emphasized that they have limited authority over counties and no way to force them to do anything. The department’s only means of enforcement, Storr wrote, is to put a jail on probation, then revoke certification — if the jail in question even was certified in the first place — and require the county to contract with another provider.

LeGrand said a law without teeth is effectively optional. “The department’s not really in a good position to boss counties around,” he said.

James Tucker, an attorney and the director of the Alabama Disabilities Advocacy Program, which has sued that state over its civil commitment process, said the agency has a responsibility to make sure counties are treating people properly. “You don’t discharge that duty by sitting on your hands and waiting for every local sheriff to report in,” he said.

Bailey’s department encourages counties to connect families with outpatient services in order to avoid the commitment process. If someone does need to be committed, the department said, counties should hold people in crisis stabilization units operated by community mental health centers.

“I do not believe jails are an appropriate location to hold someone who is not charged with a crime and is awaiting admission to a treatment bed,” Bailey told Mississippi Today and ProPublica in an email. “The person should be in a safe location, receiving treatment.”

But there are only 180 crisis beds in the state, and crisis stabilization units frequently turn people away because they are full, can’t provide the needed care, or deem a patient too violent. Storr said the agency is working to reduce denials and plans to use one-time federal pandemic funding to expand capacity.

Allen, the sheriffs’ association attorney, said the state will need more crisis beds if officials want to keep people out of jail as they await mental health care. He said he’s been meeting with sheriffs and county officials since the guidance was issued.

“This has catalyzed the county governments and law enforcement to do something,” he said. Sheriffs agree on the need for “certified centers, just not in the county jail.”

Mollie Simon of ProPublica contributed research to this story.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=304973

Mississippi Today

Mississippi Legislature approves DEI ban after heated debate

Mississippi lawmakers have reached an agreement to ban diversity, equity and inclusion programs and a list of “divisive concepts” from public schools across the state education system, following the lead of numerous other Republican-controlled states and President Donald Trump’s administration.

House and Senate lawmakers approved a compromise bill in votes on Tuesday and Wednesday. It will likely head to Republican Gov. Tate Reeves for his signature after it clears a procedural motion.

The agreement between the Republican-dominated chambers followed hours of heated debate in which Democrats, almost all of whom are Black, excoriated the legislation as a setback in the long struggle to make Mississippi a fairer place for minorities. They also said the bill could bog universities down with costly legal fights and erode academic freedom.

Democratic Rep. Bryant Clark, who seldom addresses the entire House chamber from the podium during debates, rose to speak out against the bill on Tuesday. He is the son of the late Robert Clark, the first Black Mississippian elected to the state Legislature since the 1800s and the first Black Mississippian to serve as speaker pro tempore and preside over the House chamber since Reconstruction.

“We are better than this, and all of you know that we don’t need this with Mississippi history,” Clark said. “We should be the ones that say, ‘listen, we may be from Mississippi, we may have a dark past, but you know what, we’re going to be the first to stand up this time and say there is nothing wrong with DEI.'”

Legislative Republicans argued that the measure — which will apply to all public schools from the K-12 level through universities — will elevate merit in education and remove a list of so-called “divisive concepts” from academic settings. More broadly, conservative critics of DEI say the programs divide people into categories of victims and oppressors and infuse left-wing ideology into campus life.

“We are a diverse state. Nowhere in here are we trying to wipe that out,” said Republican Sen. Tyler McCaughn, one of the bill’s authors. “We’re just trying to change the focus back to that of excellence.”

The House and Senate initially passed proposals that differed in who they would impact, what activities they would regulate and how they aim to reshape the inner workings of the state’s education system. Some House leaders wanted the bill to be “semi-vague” in its language and wanted to create a process for withholding state funds based on complaints that almost anyone could lodge. The Senate wanted to pair a DEI ban with a task force to study inefficiencies in the higher education system, a provision the upper chamber later agreed to scrap.

The concepts that will be rooted out from curricula include the idea that gender identity can be a “subjective sense of self, disconnected from biological reality.” The move reflects another effort to align with the Trump administration, which has declared via executive order that there are only two sexes.

The House and Senate disagreed on how to enforce the measure but ultimately settled on an agreement that would empower students, parents of minor students, faculty members and contractors to sue schools for violating the law.

People could only sue after they go through an internal campus review process and a 25-day period when schools could fix the alleged violation. Republican Rep. Joey Hood, one of the House negotiators, said that was a compromise between the chambers. The House wanted to make it possible for almost anyone to file lawsuits over the DEI ban, while Senate negotiators initially bristled at the idea of fast-tracking internal campus disputes to the legal system.

The House ultimately held firm in its position to create a private cause of action, or the right to sue, but it agreed to give schools the ability to conduct an investigative process and potentially resolve the alleged violation before letting people sue in chancery courts.

“You have to go through the administrative process,” said Republican Sen. Nicole Boyd, one of the bill’s lead authors. “Because the whole idea is that, if there is a violation, the school needs to cure the violation. That’s what the purpose is. It’s not to create litigation, it’s to cure violations.”

If people disagree with the findings from that process, they could also ask the attorney general’s office to sue on their behalf.

Under the new law, Mississippi could withhold state funds from schools that don’t comply. Schools would be required to compile reports on all complaints filed in response to the new law.

Trump promised in his 2024 campaign to eliminate DEI in the federal government. One of the first executive orders he signed did that. Some Mississippi lawmakers introduced bills in the 2024 session to restrict DEI, but the proposals never made it out of committee. With the national headwinds at their backs and several other laws in Republican-led states to use as models, Mississippi lawmakers made plans to introduce anti-DEI legislation.

The policy debate also unfolded amid the early stages of a potential Republican primary matchup in the 2027 governor’s race between State Auditor Shad White and Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann. White, who has been one of the state’s loudest advocates for banning DEI, had branded Hosemann in the months before the 2025 session “DEI Delbert,” claiming the Senate leader has stood in the way of DEI restrictions passing the Legislature.

During the first Senate floor debate over the chamber’s DEI legislation during this year’s legislative session, Hosemann seemed to be conscious of these political attacks. He walked over to staff members and asked how many people were watching the debate live on YouTube.

As the DEI debate cleared one of its final hurdles Wednesday afternoon, the House and Senate remained at loggerheads over the state budget amid Republican infighting. It appeared likely the Legislature would end its session Wednesday or Thursday without passing a $7 billion budget to fund state agencies, potentially threatening a government shutdown.

“It is my understanding that we don’t have a budget and will likely leave here without a budget. But this piece of legislation …which I don’t think remedies any of Mississippi’s issues, this has become one of the top priorities that we had to get done,” said Democratic Sen. Rod Hickman. “I just want to say, if we put that much work into everything else we did, Mississippi might be a much better place.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

House gives Senate 5 p.m. deadline to come to table, or legislative session ends with no state budget

The House on Wednesday attempted one final time to revive negotiations between it and the Senate over passing a state budget.

Otherwise, the two Republican-led chambers will likely end their session without funding government services for the next fiscal year and potentially jeopardize state agencies.

The House on Wednesday unanimously passed a measure to extend the legislative session and revive budget bills that had died on legislative deadlines last weekend.

House Speaker Jason White said he did not have any prior commitment that the Senate would agree to the proposal, but he wanted to extend one last offer to pass the budget. White, a Republican from West, said if he did not hear from the Senate by 5 p.m. on Wednesday, his chamber would end its regular session.

“The ball is in their court,” White said of the Senate. “Every indication has been that they would not agree to extend the deadlines for purposes of doing the budget. I don’t know why that is. We did it last year, and we’ve done it most years.”

But it did not appear likely Wednesday afternoon that the Senate would comply.

The Mississippi Legislature has not left Jackson without setting at least most of the state budget since 2009, when then Gov. Haley Barbour had to force them back to set one to avoid a government shutdown.

The House measure to extend the session is now before the Senate for consideration. To pass, it would require a two-thirds majority vote of senators. But that might prove impossible. Numerous senators on both sides of the aisle vowed to vote against extending the current session, and Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann who oversees the chamber said such an extension likely couldn’t pass.

Senate leadership seemed surprised at the news that the House passed the resolution to negotiate a budget, and several senators earlier on Wednesday made passing references to ending the session without passing a budget.

“We’ll look at it after it passes the full House,” Senate President Pro Tempore Dean Kirby said.

The House and Senate, each having a Republican supermajority, have fought over many issues since the legislative session began early January.

But the battle over a tax overhaul plan, including elimination of the state individual income tax, appeared to cause a major rift. Lawmakers did pass a tax overhaul, which the governor has signed into law, but Senate leaders cried foul over how it passed, with the House seizing on typos in the Senate’s proposal that accidentally resembled the House’s more aggressive elimination plan.

The Senate had urged caution in eliminating the income tax, and had economic growth triggers that would have likely phased in the elimination over many years. But the typos essentially negated the triggers, and the House and governor ran with it.

The two chambers have also recently fought over the budget. White said he communicated directly with Senate leaders that the House would stand firm on not passing a budget late in the session.

But Senate leaders said they had trouble getting the House to meet with them to haggle out the final budget.

On the normally scheduled “conference weekend” with a deadline to agree to a budget last Saturday, the House did not show, taking the weekend off. This angered Hosemann and the Senate. All the budget bills died, requiring a vote to extend the session, or the governor forcing them into a special session.

If the Legislature ends its regular session without adopting a budget, the only option to fund state agencies before their budgets expire on June 30 is for Gov. Tate Reeves to call lawmakers back into a special session later.

“There really isn’t any other option (than the governor calling a special session),” Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann previously said.

If Reeves calls a special session, he gets to set the Legislature’s agenda. A special session call gives an otherwise constitutionally weak Mississippi governor more power over the Legislature.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Amount of federal cuts to health agencies doubles

Cuts to public health and mental health funding in Mississippi have doubled – reaching approximately $238 million – since initial estimates last week, when cancellations to federal grants allocated for COVID-19 pandemic relief were first announced.

Slashed funding to the state’s health department will impact community health workers, planned improvements to the public health laboratory, the agency’s ability to provide COVID-19 vaccinations and preparedness efforts for emerging pathogens, like H5 bird flu.

The grant cancellations, which total $230 million, will not be catastrophic for the agency, State Health Officer Dr. Daniel Edney told members of the Mississippi House Democratic Caucus at the Capitol April 1.

But they will set back the agency, which is still working to recover after the COVID-19 pandemic decimated its workforce and exposed “serious deficiencies” in the agency’s data collection and management systems.

The cuts will have a more significant impact on the state’s economy and agency subgrantees, who carry out public health work on the ground with health department grants, he said.

“The agency is okay. But I’m very worried about all of our partners all over the state,” Edney told lawmakers.

The health department was forced to lay off 17 contract workers as a result of the grant cancellations, though Edney said he aims to rehire them under new contracts.

Other positions funded by health department grants are in jeopardy. Two community health workers at Back Bay Mission, a nonprofit that supports people living in poverty in Biloxi, were laid off as a result of the cuts, according to WLOX. It’s unclear how many more community health workers, who educate and help people access health care, have been impacted statewide.

The department was in the process of purchasing a comprehensive data management system before the cuts and has lost the ability to invest in the Mississippi Public Health Laboratory, he said. The laboratory performs environmental and clinical testing services that aid in the prevention and control of disease.

The agency has worked to reduce its dependence on federal funds, Edney said, which will help it weather the storm. Sixty-six percent of the department’s budget is federally funded.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention pulled back $11.4 billion in funding to state health departments nationwide last week. The funding was originally allocated by Congress for testing and vaccination against the coronavirus as part of COVID-19 relief legislation, and to address health disparities in high-risk and underserved populations. An additional $1 billion from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration was also terminated.

“The COVID-19 pandemic is over, and HHS will no longer waste billions of taxpayer dollars responding to a non-existent pandemic that Americans moved on from years ago,” the Department of Health and Human Services Director of Communications Andrew Nixon said in a statement.

HHS did not respond to questions from Mississippi Today about the cuts in Mississippi.

Democratic attorneys general and governors in 23 states filed a lawsuit against the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Tuesday, arguing that the sudden cancellation of the funding was unlawful and seeking injunctive relief to halt the cuts. Mississippi did not join the suit.

Mental health cuts

The Department of Mental Health received about $7.5 million in cuts to federal grants from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Over half of the cuts were to community mental health centers, and supported alcohol and drug treatment services for people who can not afford treatment, housing services for parenting and pregnant women and their children, and prevention services.

The cuts could result in reduced beds at community mental health centers, Phaedre Cole, the director of Life Help and President of Mississippi Association of Community Mental Health Centers, told lawmakers April 1.

Community mental health centers in Mississippi are already struggling to keep their doors open. Four centers in the state have closed since 2012, and a third have an imminent to high risk of closure, Cole told legislators at a hearing last December.

“We are facing a financial crisis that threatens our ability to maintain our mission,” she said Dec. 5.

Cuts to the department will also impact diversion coordinators, who are charged with reducing recidivism of people with serious mental illness to the state’s mental health hospital, a program for first-episode psychosis, youth mental health court funding, school-aged mental health programs and suicide response programs.

The Department of Mental Health hopes to reallocate existing funding from alcohol tax revenue and federal block grant funding to discontinued programs.

The agency posted a list of all the services that have received funding cuts. The State Department of Health plans to post such a list, said spokesperson Greg Flynn.

Health leaders have expressed fear that there could be more funding cuts coming.

“My concern is that this is the beginning and not the end,” said Edney.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

-

Mississippi Today24 hours ago

Mississippi Today24 hours agoPharmacy benefit manager reform likely dead

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days agoSevere storms will impact Alabama this weekend. Damaging winds, hail, and a tornado threat are al…

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days agoUniversity of Alabama student detained by ICE moved to Louisiana

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed4 days agoTornado watch, severe thunderstorm warnings issued for Oklahoma

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days agoPeanut farmer wants Florida water agency to swap forest land

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Virginia News Feed5 days agoYoungkin removes Ellis, appoints Cuccinelli to UVa board | Virginia

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed6 days agoA little early morning putting at the PGA Tour Superstore

-

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed5 days agoHometown Hero | Restaurant owner serves up hope