Mississippi Today

The Emmett Till lynching has seen more than its share of liars. Is Tim Tyson one of them?

Award-winning historian Tim Tyson swears he heard admissions regarding Emmett Till’s lynching and another racial murder.

Admissions that weren’t recorded. Admissions that no one else heard. Admissions that he began hearing when he was 10.

“The question is not whether Tim Tyson fooled us once,” said Devery Anderson, author of “Emmett Till: The Murder That Shocked the World and Propelled the Civil Rights Movement.” “The question is whether he fooled us twice — and got away with it.”

Tyson has said he heard these admissions. He didn’t respond to requests for comments on the Till matter, but he has previously spoken to me, the FBI and others. All these are noted.

Tyson’s 2017 book, “The Blood of Emmett Till,” lit the bomb that exploded around the world with this claim: The white woman at the center of the Emmett Till case, Carolyn Bryant Donham, had admitted she lied when she testified that he had grabbed her around the waist and uttered obscenities.

For some in the Till family, such as his cousin, the Rev. Wheeler Parker, the revelation represented the hope of clearing his cousin’s name. “I was elated,” he said.

He had longed to hear Donham say she lied about Till and planned to forgive her when she did, said the longtime pastor. “I was raised to believe deeply in forgiveness. If you don’t forgive, God won’t forgive you.”

For some in the Till family, the revelation raised hopes of a possible prosecution. His cousin, Deborah Watts, said there should be “a revisiting of the evidence in light of this revelation,” and Bennie Thompson, the Democratic congressman for the Mississippi Delta, called for an investigation, saying this represented “an opportunity to bring some justice to an innocent 14-year-old boy.”

For Till’s cousin, Ollie Gordon, the revelation sounded like a ruse. She saw no logic, she said, in Donham sharing such information with someone she hardly knew.

“I thought, ‘Oh, here we go. This man wants to sell his book,’” she said. “He knew if he put that lie out, that was going to help him sell the book.”

The fact that Tyson spoke to Donham but no one in the Till family reflects his mindset, she said. “If you want first-hand information, you go to the family. If you want to write what you want to write, you just bypass the family.”

What Tyson did to the Till family is nothing new, she said. “People have made money off the blood of Emmett Till and the backs of the Till family. They’re all chasing the dollar. They don’t care how they get it.”

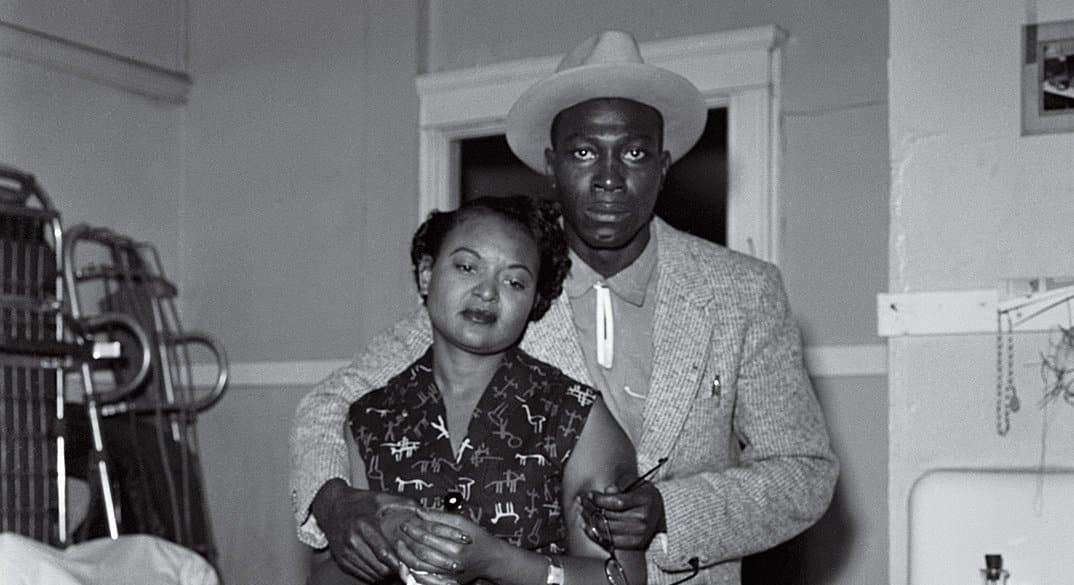

Parker still remembers the night of Aug. 28, 1955, when two men with guns stormed the Mississippi Delta home where he and his cousin, Emmett Till, were staying. He and Till had come from Chicago to visit relatives.

It was past 2 a.m., “as dark as a thousand midnights,” Parker said, when he heard angry voices from the gloom.

A flashlight shone down the hall, and he shut his eyes, ready to hear the shots that would steal his life. He trembled as he prayed, his 16 years flitting across his mind, he said. “I knew I wasn’t right with God.”

He heard the men say they “wanted the fat boy” that had “done the talking” at Bryant’s Grocery.

Before long, their steps receded and then their voices. They were gone, and so was his cousin, Emmett, whom kidnappers hauled to a remote barn and began beating.

After the first light came, Parker fled Mississippi.

For 30 years, he wasn’t asked about what he had seen, but in the decades since, he has spoken out.

While visiting one school, a white student told Parker that Till had “misbehaved” inside the store and got what he deserved.

“What could he have done to deserve that?” Parker said he responded. “I know he didn’t do anything.”

He and another cousin said they never saw Till do or say anything to Donham inside the store. All Till did was whistle at her after she walked outside, they said.

Several nights later, Till’s murderers executed their own judgment, Parker said. “They killed him for what? A whistle?”

Till’s torture lasted much of the night, and witnesses heard him screaming past dawn. By the time the sun began to peek over the horizon, his cries became fainter.

Silence followed.

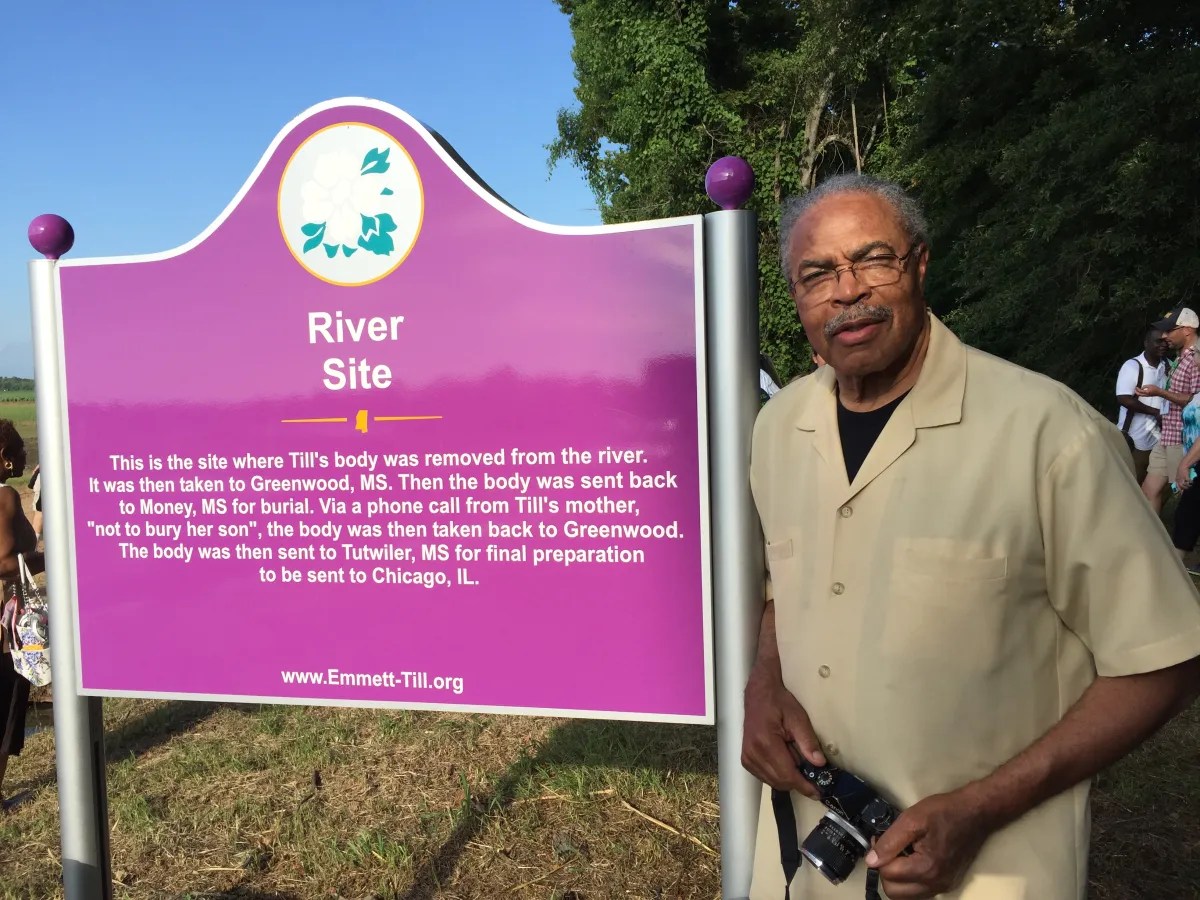

Till’s killers tried to bury their evil deeds by tying a 75-pound gin fan around his neck and tossing his body into water that fed into the Tallahatchie River.

The next day, when a deputy questioned two of the killers, J.W. Milam and Roy Bryant, they admitted they had kidnapped Till, but insisted they had released him unharmed. Days later, his body bobbed back to the river’s surface.

Sheriff Clarence Strider tried to bury Till’s brutalized body in a local cemetery to conceal the evil deed, but when his mother found out, she demanded his return to Chicago, where she opened his casket. “I wanted the world,” she said, “to see what I had seen.”

The lies continued after his funeral.

After arrests in the case, Bryant’s wife, Donham, told the defense lawyer that Till came into Bryant’s Grocery, grabbed her hand, asked for a date and said “goodbye” as he left.

But weeks later, the lawyer announced to reporters that Till had “mauled” Donham, and she echoed that lie from the witness stand. With the jury out of the courtroom, she claimed that Till had grabbed her around the waist, told her “you needn’t be afraid of me,” and said he had sex with white women before.

The sheriff got in on the lies, too. After Till was found, the sheriff told reporters the body had only been in the river a few days, released the body to a Black mortician and filled out a death certificate for Till.

But by the time the trial began, he had become a witness for the defense. He testified that the body had been in the water for at least 10 days and that he couldn’t tell the color of the skin — only that it was human. His words backed the incredulous defense claim that Till was still alive and that the NAACP had planted a cadaver in the river. (Five decades later, an autopsy and a DNA test proved that Till’s body was the one in his grave.)

The all-white jury acquitted the two men, despite believing they had killed Till, according to interviews the jurors gave Stephen Whitaker, who researched the case for his master’s thesis.

If those lies weren’t enough, journalist William Bradford Huie concealed the identities of other killers with his Look magazine article.

Huie told his editor that four men had taken part in the “torture-and-murder party,” but when the editor insisted on getting legal releases from all four, the murder party shrunk to two. (One trial witness, Willie Reed, identified four white men riding in the cab of the truck while three Black men held Till in the back.)

As for Huie, he had dreams of a Hollywood film and paid Till’s killers $3,150 for their rights.

The idea of Huie making “a deal with the murderers” angered Till’s mother, Mamie Till Mobley, and her attorney sent a cease and desist letter to United Artists, said Till documentary filmmaker Keith Beauchamp.

Huie’s 1956 article became gospel in the Till case until a new FBI investigation almost a half century later. Dale Killinger, who conducted that probe, said “the damage from those lies was deeper and broader than just Till’s murder.”

Three months before Till was killed, the Rev. George Lee was assassinated because he helped Black Mississippians register to vote in Belzoni. The sheriff claimed the shotgun pellets found in Lee’s face were loose fillings from his teeth.

Lamar Smith was gunned down in broad daylight on the courthouse lawn in Brookhaven. Despite the killer being covered in blood, the sheriff maintained there were no witnesses.

Killinger said these types of killings — and the lies that made them possible — “perpetuated generational trauma.”

By age 7, Tim Tyson was already spinning yarns.

He and his best friend “would lie there in the dark in the twin beds, and I would tell him stories, making them up as I went,” Tyson wrote in his memoir, “Blood Done Signed My Name.”

With each concocted tale, his friend cheered him on. “His fierce and unfeigned enthusiasm for these rambling odysseys,” Tyson wrote, “was like a drug to me.”

His friend even coined a name for them: “Tim’s Tall Tales.”

By the time Tyson telephoned me in 2008, he was already mesmerizing audiences with his stories of growing up in Oxford, North Carolina, and his memoir was being made into a movie.

Over lunch at Hal & Mal’s in Jackson, Tyson, who serves as a senior research scholar for the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University, told me he landed an interview with Donham, the first interview I had ever heard of her giving to a historian. I congratulated him.

We talked about the Till case and much of the lore surrounding it.

Months later, we met in Jackson, he said he had finished talking with her. He told me her story mirrored her testimony, where she claimed Till had mauled her.

“You know she lied, don’t you?” I asked.

The statement surprised him, and afterward, I mailed him a copy of the statement she had made to the defense lawyer, where she mentioned nothing about Till grabbing her or talking about having sex with her.

He used that statement in his book and tried to talk with Donham again. She turned him down.

Much to my surprise, “The Blood of Emmett Till” hit the shelves in 2017 with the claim that Donham had admitted to Tyson that she had lied when she testified that Till had grabbed her around the waist and uttered obscenities.

News of the revelation spread like wildfire, first through top publications and television stations, before hitting Black radio, television, websites and word of mouth. “The Blood of Emmett Till” shot onto The New York Times Bestseller List and won the Robert F. Kennedy Award.

Calls arose for her prosecution, and the Justice Department began to look at the Till case again.

Questions soon surfaced. A source told me that Donham’s family was saying she didn’t recant, and I telephoned her then-daughter-in-law, Marsha Bryant, who said she was present the whole time and never heard the quotation Tyson attributed to Donham. Bryant said she had a copy of the transcript and the quote wasn’t in it.

When I reached out to Tyson in 2018, he confirmed he didn’t have the bombshell quote on tape, saying he was still setting up his recorder.

The book “Till” opens with Donham drinking coffee and serving Tyson a slice of pound cake. “She had never opened her door to a journalist or historian, let alone invited one for cake and coffee,” he wrote.

Bryant said Tyson actually brought the cake himself, and after the interview, he took it back with him.

Tyson told me his recorder wasn’t working when Donham said, “They’re all dead now anyway,” so he snatched up his notebook, began scribbling notes and heard her recantation.

But when the FBI began to investigate the matter, he gave investigators multiple accounts: that his recorder wasn’t working, that his recording was lost, that he didn’t realize he didn’t have her recantation on tape until much later.

Tyson wrote that Donham handed him a trial transcript and the memoir. Bryant disputed that, saying Donham never handed Tyson anything.

Tyson wrote that after Donham handed him the transcript, she said, “That part is not true.”

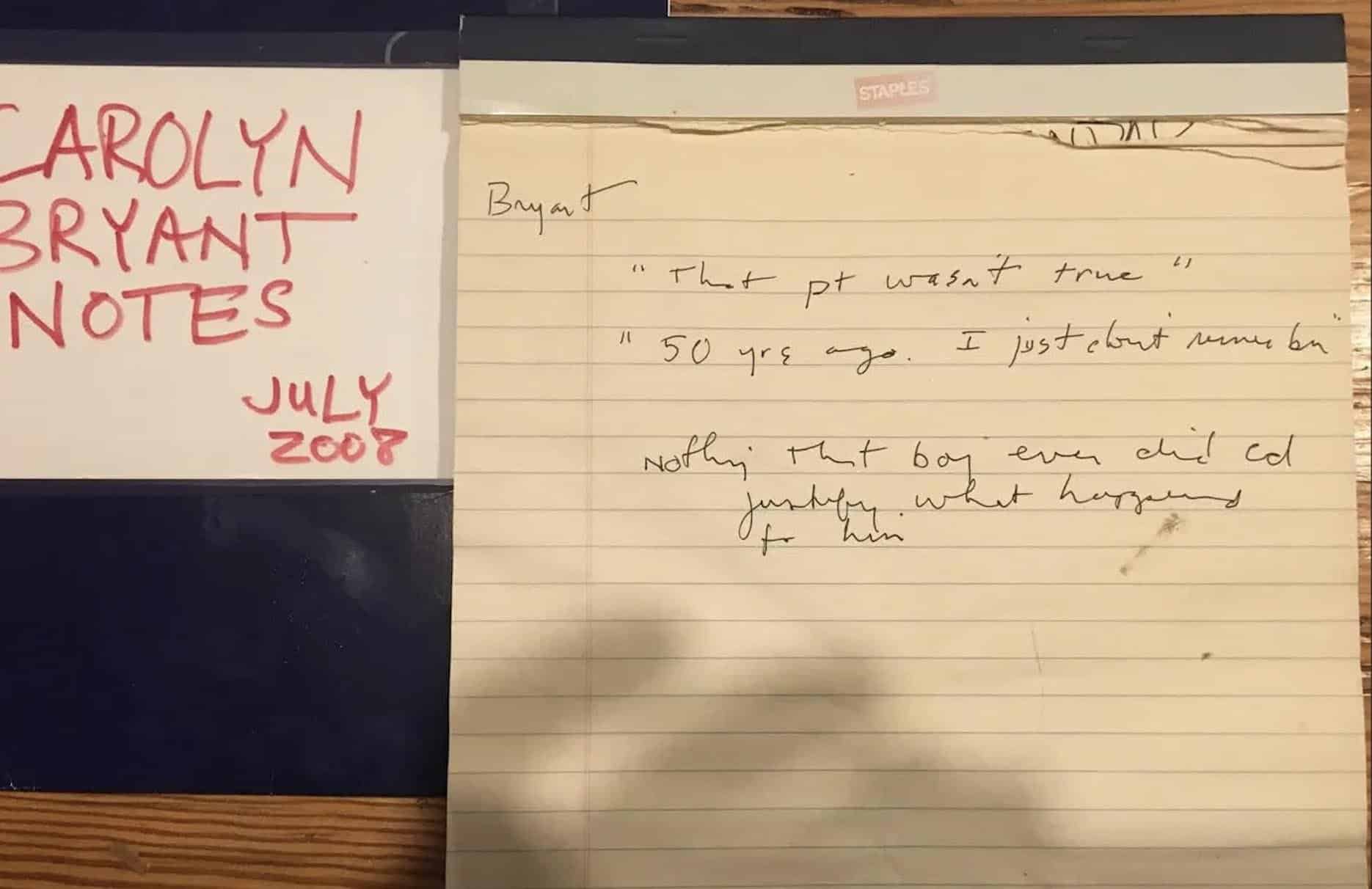

Tyson emailed me a photograph of his undated notes, which he shared with the FBI: “That pt wasn’t true. … 50 yrs ago. I just don’t remember. … Nothing that boy ever did could justify what happened to him.”

The way the quote appears in the “Till” book (italics show the words missing from the notes): “They’re all dead now anyway. … I want to tell you. Honestly, I just don’t remember. It was 50 years ago. You tell these stories for so long that they seem true, but that part is not true. … Nothing that boy ever did could justify what happened to him.”

Tyson told me Donham’s recantation took place in July 2008.

The problem with that date? He hadn’t met her yet, according to emails he wrote in August 2008 to her family.

Asked by email how he could have interviewed Donham in July 2008 when he had yet to meet her then, Tyson did not reply.

Tyson said Bryant didn’t take exception to “any of the facts” in the book, but was upset about people posting pictures of their house on the Internet.

Bryant told me she did object and shared an email with the FBI that she had sent Tyson, wanting to know why he was saying Donham had admitted she lied.

Bryant wrote Donham’s memoir, “I Am More Than a Wolf Whistle: The Story of Carolyn Bryant Donham,” and shared a copy with Tyson, who said in an August 2008 email that the work would prove “invaluable to history.”

Bryant said Tyson agreed to act as an editor for the book — a claim he told me was “bullsh–.”

But emails and edited versions of Donham’s memoir show Tyson edited the book, suggested revisions and rewrote the preface. The Department of Justice’s report also noted Tyson’s editing.

In a note Tyson put at the top of Donham’s memoir on March 6, 2009, he wrote, “Dear Marsha and Carolyn: I am sorry to take so long getting this back to you. I enjoyed reading it. But editing is hard work …

“Read over my edits and comments. I think they may suggest to you some of the broad outlines for another revision. When you finish another version — there will be several more, which is the nature of the publication process — you may feel free to send it to me. … You’ve done a great job thus far.”

He emailed Bryant and asked her to list him as “editor of the final project, since I am a professional scholar who has a boss (the dean) who wants to know how I spent my time and energy. ‘Editor’ can go on my annual report and suggest to the dean that I don’t just sit around and drink coffee and read the newspaper, regardless of what my wife and children might report to the contrary.”

Bryant believes it was “unethical” for him to serve as her editor and then take passages from her book to use in his own publication, she said. “He denied being my editor. It’s pretty damn obvious he was my editor.”

She said she is even angrier that Tyson recently made public a copy of her book, she said. “It appears to me that he is trying to inject himself into the Emmett Till story again by making sure he’s front and center.”

Tyson denied to the FBI that he ever agreed to assist Bryant in getting the memoir published, but in his first email to the family in August 2008, he wrote, “ think you should try to publish this book, and I will be glad to offer what help I can, including introducing you to my agent.”

At no point in Donham’s memoir, the two interviews she gave Tyson or the interviews she gave the FBI does she say she recanted. In fact, in her memoir, she doubled down on the claim that Till attacked her. She even made the head-scratching claim that when Till’s kidnappers asked her if he was the one who attacked her in the store, she refused to say — only for Till to identify himself to his kidnappers.

One of the biggest questions the FBI had for Tyson was why, after Donham recanted, he never asked her to repeat her statement or quiz her about this contradiction. He told the FBI that he didn’t want to interrupt the “flow” of the conversation, but he interrupted her at other times to clarify points, the Justice Department noted in its report closing the Till case.

Tyson had other opportunities in his editing of the memoir. He wrote many suggestions and questions about the book, but he never asked Donham a single question about what he claimed was her recantation.

The FBI asked Tyson why he failed to share this important evidence with authorities for nearly a decade, and he replied that he thought the case was closed.

When investigators interviewed Tyson, “rather than obtaining other corroborating evidence to support Tyson’s claim that … [Donham] offered a recantation,” the report said, “investigators instead identified numerous inconsistencies in Tyson’s account that raised questions about the credibility of his account of the interviews.”

In closing the Till case on Dec. 6, 2021, the Justice Department said, “Tyson’s account lacks credibility,” citing his “shifting explanations to FBI investigators …, the questionable nature of his relationship with [Donham], and his financial motives.”

Sixteen months later, Donham died — and with it any hope of a prosecution in the Till case.

After discovering these things about “The Blood of Emmett Till,” I reached out to a historian, who told me, “You know there were problems with Tyson’s previous book.”

That was news to me. Researcher Brandon Arvesen and I dove deeper into “Blood Done Sign My Name.”

The book centers on the May 11, 1970 killing of Henry Marrow, a 23-year-old Black man killed by members of the Teel family. After his slaying, Robert and Larry Teel turned themselves in to authorities, who moved them from a local jail to a prison in Raleigh 40 miles away, according to newspaper accounts.

The book opens with Tyson claiming his 10-year-old friend, Gerald Teel, told him in person on the evening of May 12, 1970, that his father, Robert, and his brother, Roger, shot “a n—–” last night in Oxford, North Carolina.

One problem with this claim? The Teel family may have already left town for safety reasons to Mount Olive, more than 100 miles away, according to newspaper reports.

The Feb. 21, 1971, Durham Herald-Sun newspaper says Teel’s sons “did not return to school in Oxford after May 11. Instead they were enrolled in classes in Mount Olive where they finished out the term.”

Tyson did not reply to calls and emails regarding this question.

This is far from the only issue with the book. “Name” has some faulty footnotes, wrong details, wrong dates for events and wrong quotations.

For instance, Tyson quoted Black businessman James Gregory as saying, “Even some black folks want to believe we’ve made a lot of progress in race relations, but deep down they know things are bad.”

Tyson attributed the quote to the May 29, 1970, issue of the Raleigh News and Observer. The actual quote from Gregory, published a day earlier, said, “Outsiders are responsible for all of this.”

During their murder trial, Robert and Larry Teel claimed self-defense.

Robert Teel’s stepson, Roger Oakley, became the defense’s surprise witness, claiming he was the one who fired the fatal shot, but accidentally, of course. A jury acquitted the Teels, and a Raleigh News and Observer editorial called the verdict a “sham and mockery.”

Thirteen years later, Tyson interviewed the father, Robert Teel, for a master’s thesis.

The Teel family shared what they say is a handwritten contract that Tyson signed and gave them at the time: “In exchange for above cooperation, Mr. Tyson will, upon graduation from law school, represent Mr. [Robert] Teel as his legal counsel in a legal action of Mr. Teel’s choice, without retainer’s fee, on a 50%/50% contractual basis, … immediately upon graduation to perform above legal action in a prompt manner.” (Tyson has a doctorate in history, but his Duke University biography makes no mention of law school.)

After Tyson wrote “Blood Done Sign My Name,” he donated a copy of his master’s thesis to the Thornton Library in Oxford and said in the author’s note that someone had torn out several pages about Marrow’s killing, “presumably to prevent other people from reading them.”

The thesis has since disappeared from the library, but Mississippi Today has obtained a copy of the entire thesis, including the missing pages, which differs from “Name.”

In his thesis, Tyson wrote that Marrow “walked down to Freeman’s store and returned with a six pack of Country Club Malt Liquor,” but in “Name,” Tyson wrote that Marrow went to Teel’s convenience store to get a big Pepsi and something to eat.

Robert Teel ran a car wash, according to newspaper articles at the time. He also operated a barber shop, a coin-operated laundromat and a cycle shop, according to the Feb. 16, 1971, Oxford Public Ledger. The newspaper mentions nothing about a convenience store, and Teel’s son, Larry, said they never had one.

As with his Till book, Tyson didn’t interview the victim’s family.

When Till’s cousin, Parker, found out that Donham, the white woman at the center of the case, denied she had ever recanted and there was no recording, his heart sank, he said. “It was a blow.”

Tyson “did some big lying,” said Parker, whose book with Chris Benson, “A Few Days Full of Trouble: Revelations on the Journey to Justice for My Cousin and Best Friend, Emmett Till,” was published in January. “He said he had a recorder, but everything is missing.”

Tyson has defended the recantation, telling The New York Times that he took detailed notes: “Carolyn started spilling the beans before I got the recorder going. I documented her words carefully. My reporting is rock solid.”

Till’s cousin, Gordon, said for the author to make things right to the Till family, he would need to apologize for the harm he has caused them. “He would have to admit he fabricated this,” she said.

Tyson did not reply to a request for comment on the Till family’s remarks.

After the release of his Till book in 2017, CBS This Morning interviewed Tyson about the bombshell quote from Donham, whom he suggested had recanted because she was remorseful.

“We’re not punished for our sins; we’re punished by our sins,” he told Gayle King. “Nobody ever gets away with anything.”

Researcher Brandon Arvesen contributed to this report.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Meet Willye B. White: A Mississippian we should all celebrate

In an interview years and years ago, the late Willye B. White told me in her warm, soothing Delta voice, “A dream without a plan is just a wish. As a young girl, I had a plan.”

She most definitely did have a plan. And she executed said plan, as we shall see.

And I know what many readers are thinking: “Who the heck was Willye B. White?” That, or: “Willye B. White, where have I heard that name before?”

Well, you might have driven an eight-mile, flat-as-a-pancake stretch of U.S. 49E, between Sidon and Greenwood, and seen the marker that says: “Willye B. White Memorial Highway.” Or you might have visited the Olympic Room at the Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame and seen where White was a five-time participant and two-time medalist in the Summer Olympics as a jumper and a sprinter.

If you don’t know who Willye B. White was, you should. Every Mississippian should. So pour yourself a cup of coffee or a glass of iced tea, follow along and prepare to be inspired.

Willye B. White was born on the last day of 1939 in Money, near Greenwood, and was raised by grandparents. As a child, she picked cotton to help feed her family. When she wasn’t picking cotton, she was running, really fast, and jumping, really high and really long distances.

She began competing in high school track and field meets at the age of 10. At age 11, she scored enough points in a high school meet to win the competition all by herself. At age 16, in 1956, she competed in the Summer Olympics at Melbourne, Australia.

Her plan then was simple. The Olympics, on the other side of the world, would take place in November. “I didn’t know much about the Olympics, but I knew that if I made the team and I went to the Olympics, I wouldn’t have to pick cotton that year. I was all for that.”

Just imagine. You are 16 years old, a high school sophomore, a poor Black girl. You are from Money, Mississippi, and you walk into the stadium at the Melbourne Cricket Grounds to compete before a crowd of more than 100,000 strangers nearly 10,000 miles from your home.

She competed in the long jump. She won the silver medal to become the first-ever American to win a medal in that event. And then she came home to segregated Mississippi, to little or no fanfare. This was the year after Emmett Till, a year younger than White, was brutally murdered just a short distance from where she lived.

“I used to sit in those cotton fields and watch the trains go by,” she once told an interviewer. “I knew they were going to some place different, some place into the hills and out of those cotton fields.”

Her grandfather had fought in France in World War I. “He told me about all the places he saw,” White said. “I always wanted to travel and see the places he talked about.”

Travel, she did. In the late 1950s there were two colleges that offered scholarships to young, Black female track and field athletes. One was Tuskegee in Alabama, the other was Tennessee State in Nashville. White chose Tennessee State, she said, “because it was the farthest away from those cotton fields.”

She was getting started on a track and field career that would take her, by her own count, to 150 different countries across the globe. She was the best female long jumper in the U.S. for two decades. She competed in Olympics in Melbourne, Rome, Tokyo, Mexico City and Munich. She would compete on more than 30 U.S. teams in international events. In 1999, Sports Illustrated named her one of the top 100 female athletes of the 20th century.

Chicago became White’s home for most of adulthood. This was long before Olympic athletes were rich, making millions in endorsements and appearance fees. She needed a job, so she became a nurse. Later on, she became an public health administrator as well as a coach. She created the Willye B. White Foundation to help needy children with health and after school care.

In 1982, at age 42, she returned to Mississippi to be inducted into the Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame and was welcomed back to a reception at the Governor’s Mansion by Gov. William Winter, who introduced her during induction ceremonies. Twenty-six years after she won the silver medal at Melbourne, she called being hosted and celebrated by the governor of her home state “the zenith of her career.”

Willye B. White died of pancreatic cancer in a Chicago hospital in 2007. While working on an obituary/column about her, I talked to the late, great Ralph Boston, the three-time Olympic long jump medalist from Laurel. They were Tennessee State and U.S. Olympic teammates. They shared a healthy respect from one another, and Boston clearly enjoyed talking about White.

At one point, Ralph asked me, “Did you know Willye B. had an even more famous high school classmate.”

No, I said, I did not.

“Ever heard of Morgan Freeman?” Ralph said, laughing.

Of course.

“I was with Morgan one time and I asked him if he ever ran track,” Ralph said, already chuckling about what would come next.

“Morgan said he did not run track in high school because he knew if he ran, he’d have to run against Willye B. White, and Morgan said he didn’t want to lose to a girl.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Mississippi Today

Early voting proposal killed on last day of Mississippi legislative session

Mississippi will remain one of only three states without no-excuse early voting or no-excuse absentee voting.

Senate leaders, on the last day of their regular 2025 session, decided not to send a bill to Gov. Tate Reeves that would have expanded pre-Election Day voting options. The governor has been vocally opposed to early voting in Mississippi, and would likely have vetoed the measure.

The House and Senate this week overwhelmingly voted for legislation that established a watered-down version of early voting. The proposal would have required voters to go to a circuit clerk’s office and verify their identity with a photo ID.

The proposal also listed broad excuses that would have allowed many voters an opportunity to cast early ballots.

The measure passed the House unanimously and the Senate approved it 42-7. However, Sen. Jeff Tate, a Republican from Meridian who strongly opposes early voting, held the bill on a procedural motion.

Senate Elections Chairman Jeremy England chose not to dispose of Tate’s motion on Thursday morning, the last day the Senate was in session. This killed the bill and prevented it from going to the governor.

England, a Republican from Vancleave, told reporters he decided to kill the legislation because he believed some of its language needed tweaking.

The other reality is that Republican Gov. Tate Reeves strongly opposes early voting proposals and even attacked England on social media for advancing the proposal out of the Senate chamber.

England said he received word “through some sources” that Reeves would veto the measure.

“I’m not done working on it, though,” England said.

Although Mississippi does not have no-excuse early voting or no-excuse absentee voting, it does have absentee voting.

To vote by absentee, a voter must meet one of around a dozen legal excuses, such as temporarily living outside of their county or being over 65. Mississippi law doesn’t allow people to vote by absentee purely out of convenience or choice.

Several conservative states, such as Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas and Florida, have an in-person early voting system. The Republican National Committee in 2023 urged Republican voters to cast an early ballot in states that have early voting procedures.

Yet some Republican leaders in Mississippi have ardently opposed early voting legislation over concerns that it undermines election security.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

.

Mississippi Today

Mississippi Legislature approves DEI ban after heated debate

Mississippi lawmakers have reached an agreement to ban diversity, equity and inclusion programs and a list of “divisive concepts” from public schools across the state education system, following the lead of numerous other Republican-controlled states and President Donald Trump’s administration.

House and Senate lawmakers approved a compromise bill in votes on Tuesday and Wednesday. It will likely head to Republican Gov. Tate Reeves for his signature after it clears a procedural motion.

The agreement between the Republican-dominated chambers followed hours of heated debate in which Democrats, almost all of whom are Black, excoriated the legislation as a setback in the long struggle to make Mississippi a fairer place for minorities. They also said the bill could bog universities down with costly legal fights and erode academic freedom.

Democratic Rep. Bryant Clark, who seldom addresses the entire House chamber from the podium during debates, rose to speak out against the bill on Tuesday. He is the son of the late Robert Clark, the first Black Mississippian elected to the state Legislature since the 1800s and the first Black Mississippian to serve as speaker pro tempore and preside over the House chamber since Reconstruction.

“We are better than this, and all of you know that we don’t need this with Mississippi history,” Clark said. “We should be the ones that say, ‘listen, we may be from Mississippi, we may have a dark past, but you know what, we’re going to be the first to stand up this time and say there is nothing wrong with DEI.'”

Legislative Republicans argued that the measure — which will apply to all public schools from the K-12 level through universities — will elevate merit in education and remove a list of so-called “divisive concepts” from academic settings. More broadly, conservative critics of DEI say the programs divide people into categories of victims and oppressors and infuse left-wing ideology into campus life.

“We are a diverse state. Nowhere in here are we trying to wipe that out,” said Republican Sen. Tyler McCaughn, one of the bill’s authors. “We’re just trying to change the focus back to that of excellence.”

The House and Senate initially passed proposals that differed in who they would impact, what activities they would regulate and how they aim to reshape the inner workings of the state’s education system. Some House leaders wanted the bill to be “semi-vague” in its language and wanted to create a process for withholding state funds based on complaints that almost anyone could lodge. The Senate wanted to pair a DEI ban with a task force to study inefficiencies in the higher education system, a provision the upper chamber later agreed to scrap.

The concepts that will be rooted out from curricula include the idea that gender identity can be a “subjective sense of self, disconnected from biological reality.” The move reflects another effort to align with the Trump administration, which has declared via executive order that there are only two sexes.

The House and Senate disagreed on how to enforce the measure but ultimately settled on an agreement that would empower students, parents of minor students, faculty members and contractors to sue schools for violating the law.

People could only sue after they go through an internal campus review process and a 25-day period when schools could fix the alleged violation. Republican Rep. Joey Hood, one of the House negotiators, said that was a compromise between the chambers. The House wanted to make it possible for almost anyone to file lawsuits over the DEI ban, while Senate negotiators initially bristled at the idea of fast-tracking internal campus disputes to the legal system.

The House ultimately held firm in its position to create a private cause of action, or the right to sue, but it agreed to give schools the ability to conduct an investigative process and potentially resolve the alleged violation before letting people sue in chancery courts.

“You have to go through the administrative process,” said Republican Sen. Nicole Boyd, one of the bill’s lead authors. “Because the whole idea is that, if there is a violation, the school needs to cure the violation. That’s what the purpose is. It’s not to create litigation, it’s to cure violations.”

If people disagree with the findings from that process, they could also ask the attorney general’s office to sue on their behalf.

Under the new law, Mississippi could withhold state funds from schools that don’t comply. Schools would be required to compile reports on all complaints filed in response to the new law.

Trump promised in his 2024 campaign to eliminate DEI in the federal government. One of the first executive orders he signed did that. Some Mississippi lawmakers introduced bills in the 2024 session to restrict DEI, but the proposals never made it out of committee. With the national headwinds at their backs and several other laws in Republican-led states to use as models, Mississippi lawmakers made plans to introduce anti-DEI legislation.

The policy debate also unfolded amid the early stages of a potential Republican primary matchup in the 2027 governor’s race between State Auditor Shad White and Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann. White, who has been one of the state’s loudest advocates for banning DEI, had branded Hosemann in the months before the 2025 session “DEI Delbert,” claiming the Senate leader has stood in the way of DEI restrictions passing the Legislature.

During the first Senate floor debate over the chamber’s DEI legislation during this year’s legislative session, Hosemann seemed to be conscious of these political attacks. He walked over to staff members and asked how many people were watching the debate live on YouTube.

As the DEI debate cleared one of its final hurdles Wednesday afternoon, the House and Senate remained at loggerheads over the state budget amid Republican infighting. It appeared likely the Legislature would end its session Wednesday or Thursday without passing a $7 billion budget to fund state agencies, potentially threatening a government shutdown.

“It is my understanding that we don’t have a budget and will likely leave here without a budget. But this piece of legislation …which I don’t think remedies any of Mississippi’s issues, this has become one of the top priorities that we had to get done,” said Democratic Sen. Rod Hickman. “I just want to say, if we put that much work into everything else we did, Mississippi might be a much better place.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

-

Mississippi Today3 days ago

Mississippi Today3 days agoPharmacy benefit manager reform likely dead

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed6 days agoTornado watch, severe thunderstorm warnings issued for Oklahoma

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Georgia News Feed6 days agoGeorgia road project forcing homeowners out | FOX 5 News

-

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed7 days agoHometown Hero | Restaurant owner serves up hope

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed4 days agoTornado practically rips Bullitt County barn in half with man, several animals inside

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Georgia News Feed7 days agoBudget cuts: Senior Citizens Inc. and other non-profits worry for the future

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days agoStrangers find lost family heirloom at Cocoa Beach

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days agoRepublicans look to maintain majority in Congress ahead of Florida special election