Maxiphoto/iStock via Getty Images Plus

A cluster of people talking on social media about their mysterious rashes. A sudden die-off of birds at a nature preserve. A big bump in patients showing up to a city’s hospital emergency rooms.

These are the kinds of events that public health officials are constantly on the lookout for as they watch for new disease threats.

Health emergencies can range from widespread infectious disease outbreaks to natural disasters and even acts of terrorism. The scope, timing or unexpected nature of these events can overwhelm routine health care capacities.

I am a public health expert with a background in strengthening health systems, infectious disease surveillance and pandemic preparedness.

Rather than winging it when an unusual health event crops up, health officials take a systematic approach. There are structures in place to collect and analyze data to guide their response. Public health surveillance is foundational for figuring out what’s going on and hopefully squashing any outbreak before it spirals out of control.

Tracking day by day

Indicator-based surveillance is the routine, systematic collection of specific health data from established reporting systems. It monitors trends over time; the goal is to detect anomalies or patterns that may signal a widespread or emerging public health threat.

Hospitals are legally required to report data on admissions and positive test results for specific diseases, such as measles or polio, to local health departments. The local health officials then compile the pertinent data and share it with state or national public health agencies, such as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

When doctors diagnose a positive case of influenza, for example, they report it through the National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System, which tracks respiratory and gastrointestinal illnesses. A rise in the number of cases could be a warning sign of a new outbreak. Likewise, the National Syndromic Surveillance Program collects anonymized data from emergency departments about patients who report symptoms such as fever, cough or respiratory distress.

Public health officials keep an eye on wastewater as well. A variety of pathogens shed by infected people, who may be asymptomatic, can be identified in sewage. The CDC created the National Wastewater Surveillance System to help track the virus that causes COVID-19. Since the pandemic, it’s expanded in some areas to monitor additional pathogens, including influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and norovirus. Wastewater surveillance adds another layer of data, allowing health officials to catch potential outbreaks in the community, even when many infected individuals show no symptoms and may not seek medical care.

Having these surveillance systems in place allows health experts to detect early signs of possible outbreaks and gives them time to plan and respond effectively.

Jeffrey Basinger/Newsday via Getty Images

Watching for anything outside the norm

Event-based surveillance watches in real time for anything that could indicate the start of an outbreak.

This can look like health officials tracking rumors, news articles or social media mentions of unusual illnesses or sudden deaths. Or it can be emergency room reports of unusual spikes in numbers of patients showing up with specific symptoms.

Local health care workers, community leaders and the public all support this kind of public health surveillance when they report unexpected health events through hotlines and online forms or just call, text or email their public health department. Local health workers can assess the information and escalate it to state or national authorities.

Public health officials have their ears to the ground in these various ways simultaneously. When they suspect the start of an outbreak, a number of teams spring into action, deploying different, coordinated responses.

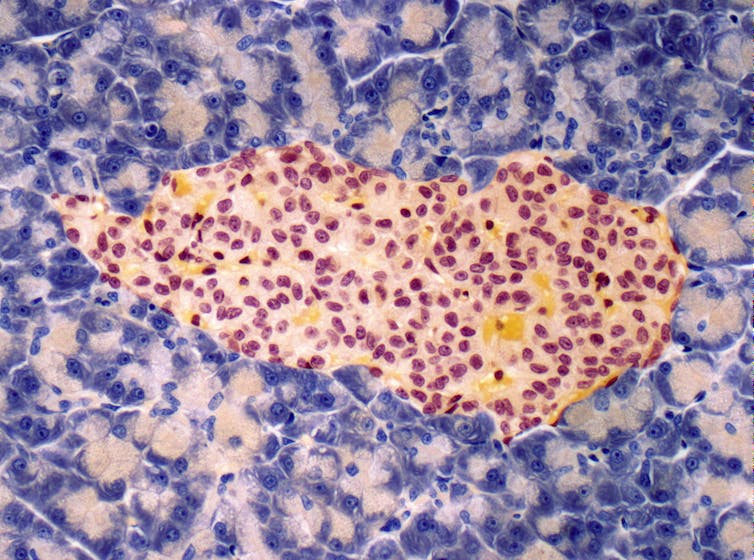

Collecting samples for more analysis

Once event-based surveillance has picked up an unusual report or a sudden pattern of illness, health officials try to gather medical samples to get more information about what might be going on. They may focus on people, animals or specific locations, depending on the suspected source. For example, during an avian flu outbreak, officials take swabs from birds, both live and dead, and blood samples from people who have been exposed.

Health workers collect material ranging from nose or throat swabs, fecal, blood or tissue samples, and water and soil samples. Back in specialized laboratories, technicians analyze the samples, trying to identify a specific pathogen, determine whether it is contagious and evaluate how it might spread. Ultimately, scientists are trying to figure out the potential impact on public health.

Finding people who may have been exposed

Once an outbreak is detected, the priority quickly shifts to containment to prevent further spread. Public health officials turn into detectives, working to identify people who may have had direct contact with a known infected person. This process is called contact tracing.

Often, contact tracers work backward from a positive laboratory confirmation of the index case – that is, the first person known to be infected with a particular pathogen. Based on interviews with the patient and visiting places they had been, the local health department will reach out to people who may have been exposed. Health workers can then provide guidance about how to monitor potential symptoms, arrange testing or advise about isolating for a set amount of time to prevent further spread.

Gabe Ginsberg/Experience Strategy Associates via Getty Images

Contact tracing played a pivotal role during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, helping health departments monitor possible cases and take immediate action to protect public health. By focusing on people who had been in close contact with a confirmed case, public health agencies could break the chain of transmission and direct critical resources to those who were affected.

Though contact tracing is labor- and resource-intensive, it is a highly effective method of stopping outbreaks before they become unmanageable. In order for contact tracing to be effective, though, the public has to cooperate and comply with public health measures.

Stopping an outbreak before it’s a pandemic

Ultimately, public health officials want to keep as many people as possible from getting sick. Strategies to try to contain an outbreak include isolating patients with confirmed cases, quarantining those who have been exposed and, if necessary, imposing travel restrictions. For cases involving animal-to-human transmission, such as bird flu, containment measures may also include strict protocols on farms to prevent further spread.

Health officials use predictive models and data analysis tools to anticipate spread patterns and allocate resources effectively. Hospitals can streamline infection control based on these forecasts, while health care workers receive timely updates and training in response protocols. This process ensures that everyone is informed and ready to act to maximize public safety.

No one knows what the next emerging disease will be. But public health workers are constantly scanning the horizon for threats and ready to jump into action.![]()

John Duah, Assistant Professor of Health Services Administration, Auburn University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.