Mississippi Today

Q&A: Growing Resilience in the South founder Sadé Meeks

Like so many good things, Growing Resilience In The South (GRITS) was born at Sadé Meeks’ grandmother’s kitchen table.

Several years ago, the South Jackson native, a registered dietitian, was working a traditional job in her field and realizing that there was a disconnect between the information she wanted and needed to provide to patients and their receptiveness to it.

One day she and her grandmother, who is now 101 years old, were eating grits at her grandmother’s kitchen table in Yazoo City when her grandmother began to fondly tell Meeks about her garden. Meeks’ grandmother grew everything she needed in her own garden and fed her eight children in the process.

Her grandmother’s story served as a contrast to the narrative she learned in school about Black people’s relationship with food, and it encouraged her to create GRITS. Instead of combating the rise in food-related chronic disease through opaque materials, Meeks realized she can do so by connecting people and their communities to “food, improving their food literacy skills and bridging the gap between culture and nutrition.”

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Mississippi Today: What led you to create GRITS?

Meeks: I was working a traditional role at the public health department, and I felt limited and boxed in, like I couldn’t really reach people in the way that I wanted to … My grandmother had eight kids, so they grew a lot of their foods. The thing that got me was how positively (my grandmother) talked about food — cultural foods, at that. In research and in the media, I always saw Black people associated with bad eating habits, and that’s not our story. That might be part of someone’s story, but that’s not our whole story.

I kept seeing this one-sided story about what Black foods are to us. Hearing her talk was a lightbulb moment because I felt so empowered by her story. It was like, ‘These stories that I’m hearing aren’t true because my grandmother is sitting here, almost 100 years old, telling me all these things about food.’ It was empowering and refreshing to hear her talk about food in that way. I wanted to continue to tell stories about Black food and Black foodways, but also have them connected to our health, as well. That’s why I started GRITS, Growing Resilience in the South, to connect people to these stories. I also say the South is a metaphor because … the South is the genesis of Black America. I really want to connect all Black people to help them connect to food in a different way, but also a way that helps them improve their health.

MT: What programming are you most excited by?

Meeks: The book club … The book club wasn’t something I had been planning to do for a while. I’ve been reading so much since I became a dietitian. Before I became a dietitian, I got interested in books about food and foodways, and that’s how I began to dismantle narratives about Black food stereotypes — it was by reading. I kind of built this library, and I posted some of my books on Instagram. Someone asked me if I was starting a book club. I was like no, but that’s a good idea and I went with it … I was surprised by the feedback and the response I got.

The first day I posted about it, I had 40 people sign up and I didn’t do much promotion. It’s (up to), like, 70 people now. I got the mini grant right before I made the announcement, so I was able to help purchase books for people who couldn’t afford it. It’s just been a really great experience, the response and also the conversations. Sometimes I’ll read books and just want to talk about these things, but I don’t have anybody to talk about it with. Now we’re having these discussions about food equity, food sovereignty and reconnecting with foods. These are really valuable conversations that are part of the work. Part of GRITS’ work is narrative change, so when we’re having these conversations about changing the narrative with food and helping people connect with food, that’s helping the community do the work for themselves as well.

MT: What has been the most interesting or exciting text you all have read so far?

Meeks: Our first book was called “Eating While Black: Food Shaming and Race in America” by Psyche A. Williams-Forson. She recently won the James Beard Award for food issues and advocacy for that book. I’m glad we started the book club off with that book because it requires you to really unlearn some things about anti-Black racism, especially when it comes to what we eat. The book mentions how so many cultural foods have these ‘unhealthy’ parts of their food, but Black foods are the only foods that really get surveilled and criticized, and it’s not because of the food, it’s because of our race. It was really helping us unpack a lot of things about food and food shaming. Sometimes as Black people, we might food shame and not even realize it, so it was a very informative book that made you be more aware of how you think. Sometimes that can be hard conversations to have, so I’m happy GRITS was able to cultivate this safe space to have these hard conversations.

No one wants to think that the way they think is wrong or biased or anti-Black, but in reality, we all can fall victim to that in some sense. Creating a space where we can talk about that and unlearn some things has been really good. The next book is ‘Catfish Dream,’ about a farmer in the Mississippi Delta’s fight to save his family farm.

MT: Why do you think an organization like GRITS is important, specifically in Mississippi?

Meeks: I know we hear a lot about health sometimes. I didn’t want to just preach health because a lot of times when people hear health, the two things they may do are kind of shut down because they don’t feel like they can be or fit that idea of ‘healthy,’ or, two, they go to an extreme … I feel like health can look so many different ways, and GRITS’ approach to health and nutrition education is so different. Even though I am a dietitian and I do promote healthy ways, I don’t approach it with nutrition education; I approach it with stories and connecting people with culture. I think the way that I use stories and cultures as a bridge to understanding our health is unique, and I think that that’s important because of the connection it’s building.

I would be in the health department and sometimes I felt like what I was doing wasn’t as effective because the patient wasn’t connecting to what I was saying. You can preach and you can give someone all this nutrition information, but if they’re not connected to what you’re talking about, it’s not effective. Being in Mississippi is a powerful thing for me. I feel more connected to my state and to the people here than I ever have … and I think it’s because I built connections with people and there’s something powerful about that. Through GRITS, I want to help people not just build connections with food, but build connections with their community, with Mississippi, and be proud of their roots. There’s so much culture, there’s so much history, there are so many things about where we live that can empower us and I want people to feel that.

I want people to hear Mississippi and be proud because they know their history, they know how connected they are to this place. I can say I am proud. Growing up, I don’t know if I would’ve gone somewhere else and be proud to tell someone I’m from Mississippi. But I love telling people I’m from here because I know what this place has. I know how valuable Mississippi is, and I think GRITS is just another way to connect people to the state and connect them to different parts of their heritage and culture.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Candice Wilder joins Mississippi Today as new higher education reporter

Mississippi Today is pleased to announce that Candice Wilder has joined the newsroom as our newest higher education reporter.

Wilder takes over higher ed coverage from Mississippi Today reporter Molly Minta, who built the beat starting in early 2021 but has since moved to the newsroom’s team covering the city of Jackson.

“I’m thrilled to join a talented and ambitious team of journalists who provide critical news and information to Mississippians,” Wilder said. “Reporting on the state’s colleges and universities at this moment is more important now than ever. My goal is to develop thoughtful coverage and tell crucial stories that will continue to serve and reflect these communities.

Wilder, an Ohio native, was one of 19 founding staff members of Signal Cleveland, an inaugural nonprofit newsroom part of Signal Ohio. There, she developed a beat that provided accessible health news and information to residents of Cleveland. Her work has led to recognitions from the Cleveland Press Club and the Association of Healthcare Journalists.

“We couldn’t be more excited to welcome Candice to our newsroom,” said Adam Ganucheau, Mississippi Today’s editor-in-chief. “So many aspects of the higher education system are under intense scrutiny and attack across the country — from free speech to funding to accountability — and Mississippi is certainly no exception. Our colleges and universities are at the heart of critical conversations about equity, access, and the future of our state as a whole. Candice brings a sharp eye, strong reporting skills, and genuine curiosity to our team, and I’m confident that her work will help Mississippians navigate the often complicated and evolving nature of higher ed here.”

“We’re so happy to have someone with Candice Wilder’s passion and experience to pick up the mantle of higher education reporting at Mississippi Today,” said Debbie Skipper, who will serve as her editor. “Molly Minta set a high standard in our reporting in this area, and I know Candice will maintain that while offering her own professional perspective.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

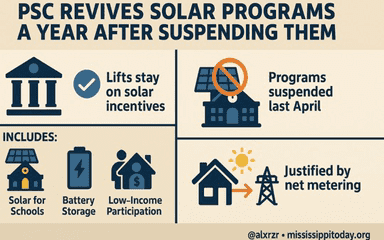

PSC revives solar programs a year after suspending them

The Mississippi Public Service Commission voted unanimously on Tuesday to lift a stay on programs offering incentives for solar power. The same commission voted to suspend the programs last April.

The PSC initially voted in 2024 to suspend three programs: “Solar for Schools,” which allows school districts to essentially build solar panels for free in exchange for tax credits, as well as incentives for battery storage and low-income participants in the state’s “distributed generation” rule. Mississippi’s “distributed generation” rule is similar to net metering in other places, but reimburses customers for less than what most states offer.

Net metering is a program where power companies — in this case Entergy Mississippi and Mississippi Power — reimburse customers who generate their own solar power, often with rooftop panels, and sell any extra power back to the grid.

The PSC suspended the programs in 2024 because, at the time, the federal government was also offering funds through its “Solar for All” initiative. The commission reasoned that the state didn’t need to add incentives, which the previous commission approved in 2022 on top of the new funding. After learning that the state government didn’t receive any “Solar for All” funding, the PSC decided on Tuesday to reverse course.

While the State of Mississippi didn’t receive any of the funding, Hope Enterprise Corp. did get $94 million last year through the program to bring solar power to low-income and disadvantaged homes in the state.

The previous PSC created the “Solar for Schools” program as a way to save school districts money on their power bills to help with other expenses. While no districts were able to make use of the program before the PSC suspended it last year, other districts have seen savings after installing solar panels. Any of the 95 school districts within the Entergy and Mississippi Power grids are eligible for the PSC incentives.

Solar advocates disagreed with the PSC’s assertion that federal “Solar for All” funding would have replaced the PSC programs, which went into effect in January 2023, arguing that the commission’s ruling would scare off potential new business. Those advocates applauded Tuesday’s reversal, saying the incentives will support professions within the solar supply chain such as electricians, roofers, manufacturers and installers.

“Yesterday’s actions by the MPSC sends a strong signal that Mississippi is open for business,” Monika Gerhart, executive director of the Gulf States Renewable Energy Industries Association, said via email. “For schools and homeowners that want to save money on their light bill, yesterday’s vote creates additional savings to install solar.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

Role reversal: Horhn celebrates commanding primary while his expected runoff challenger Mayor Lumumba’s party sours

“Somebody died in here?” asked one of the guests at the glum election watch party.

On Tuesday night, under a dozen supporters of Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba sat silently with news reporters on the low couches at a downtown marketing office, watching the results of the Democratic primary that played over muted televisions and fanning themselves in the sweltering heat.

The incumbent had nearly lost the mayoral election outright, earning 17% of the vote compared to Sen. John Horhn’s 48% in the last unofficial count of the night. It was a stacked race of 12 candidates and turnout was low – just 23% of the city’s registered voters participated.

Seven blocks away at The Rookery event venue, Horhn’s watch party was livelier. Around 8:45 p.m., about 100 supporters whooped and cheered as Horhn, his family and his pastor, Bishop Ronnie Crudup Sr., walked into the shiny marbled room.

“That appears to me to almost be a mandate, for one candidate to secure that much percentage of the vote,” Horhn, the state senator of 32 years, said.

The 2025 Democratic primary for Jackson mayor shaped up to be somewhat of a rematch, with the roles reversed this time. After meeting defeat against Lumumba in the same race in 2017, Horhn nearly avoided a runoff in the unofficial count Tuesday, securing 12,318 of the total 25,665 votes. It is his fourth time running for mayor.

“We knew it was gonna be close and had turnout been a little higher, had we worked a little harder, we might’ve been able to get there.”

Unless he receives nearly all of the mail-in absentee and affidavit votes left to be counted, Horhn will face a runoff, likely with Lumumba, on April 22. Lumumba received 4,267 votes. Tim Henderson, a retired Air Force lieutenant colonel known by few at the start of the race, finished close in third with 3,482 votes.

In a speech, Horhn thanked his father, Charlie, his family, members of the Legislative Black Caucus, and his campaign supporters, shouting out many by name, including well-known restaurateur Jeff Good, whose support of Horhn was seized on by some mayoral candidates as a reason to not vote for the state senator.

“You know, a lot has been said by some of my opponents about the fact that we were reaching out across different party lines, racial lines, socioeconomic lines, but everybody wants Jackson to do well,” he said. “And in time, Jackson will be well.”

Good’s support was one reason Horhn’s competitors in the primary tried to paint him as a Trojan Horse for white business interests in the city. He also received endorsements from sitting state representatives and the unions of public sector workers and Jackson firefighters.

“Anyone who thinks that John Horhn is bought by anyone obviously hasn’t seen the depth and breadth of the people that he’s worked for 40 years, and all the endorsements that he has received,” Good said. “The endorsements read like a who’s who of Black leadership. Those are facts. I mean, listen. This is a who’s who room. There’s former supervisors in here, there’s former state senators, current state senators, it’s amazing.”

The accusation is not grounded in a factual understanding of the Legislature, said Rep. Justis Gibbs, D-Jackson, who noted that Horhn is one of 52 senators in a statehouse led by Republicans, not Democrats.

And, Horhn’s district is larger than Jackson, so he has other cities to think about, like Edwards and Pocahontas.

“I think he has done well,” Gibbs said. “I know if I need something done … that I have an advocate, not an adversary.”

Good helped cater the watch party, with Broad Street sandwiches and Sal and Mookie’s pizza. He said he hoped Horhn could continue the vision of former mayor Harvey Johnson Jr. and finally bring a hotel to the downtown convention center, what many hoped would be the starting point of revitalizing the city.

“What was supposed to be the beginning was the end,” he said.

Last year, Lumumba was indicted on federal charges alleging he took bribes in the form of campaign donations from supposed developers of that same property in exchange for moving up a proposal deadline. He pleaded not guilty and his trial is scheduled for 2026.

“I am going to be clear that I am not guilty of any wrongdoing. I am not guilty of any wrongdoing,” Lumumba told reporters after the election results. “I admit that I love this city so much, and I am going to fight relentlessly in order to make sure that everybody gets the quality of life they deserve.”

Lumumba arrived at the Fahrenheit Creative Group office for his watch party, a location change from the luxury bed and breakfast where it was originally planned, a little after 9:30 p.m.. His wife Ebony and their two daughters accompanied him. He chalked up his low performance in the race to misinformation.

“When they tell Republicans to vote in the Democratic primary, we should not be standing here,” Lumumba said, dabbing at his brow. “They gave every reason for us not to be standing here, and yet we are standing here.”

One guest, Amina Scott, said she’s supporting Lumumba no matter what.

“He’s the only option for people in the city of Jackson as a progressive city that’s run by progressive American people,” Scott said.

She points to attempts by the state to take over Jackson Public Schools and the airport.

“It’s not a new concept that has happened in cities across this country where Black people run the cities and states to try to take them back, and they’re doing the same thing to Jackson,” she said.

“…We have to look at our history and understand it’s not a new thing and it’s an old game, and we need to win this time. And the only way we can do that is as a unit.”

Lumumba became mayor in 2017 after winning 55% of more than 34,000 total votes in the Democratic primary against eight challengers, including the incumbent, making a runoff unnecessary. Horhn, who was running for his third time that year, came in second to Lumumba with 21% of the vote. After his first term, Lumumba won reelection after receiving 69% of the vote in the Democratic primary in 2021 with under 20,000 Jacksonians turning out.

The 2025 election saw similarly low voter turnout of under 25,700 votes in the last tally of the night. Mail-in absentee ballots and affidavit ballots are still left to be counted. With all of the issues voters had identifying their correct precinct due to redistricting last year, an election official said they saw a higher number of affidavit ballots – those cast due to irregularities at the polls.

The 2025 election represented a drop in nearly 10,000 votes from 2017, but the city has lost more than that in population during that time.

If Horhn is victorious, his pastor Bishop Ronnie Crudup Sr. said he hopes Horhn can hit the ground running to reverse depopulation in Jackson, which has experienced some of the steepest losses in the country since the last census.

“We’re in a really tough and hurtful place in the city of Jackson right now,” he said. “Years ago, we experienced white flight in Jackson to the suburbs, and now we’re experiencing Black flight. People are feeling hopeless.”

Johnnie Patton, whose family owns the Big Apple Inn, a famous restaurant on downtown’s historic Farish Street, said she wants to see Jackson return to the city she knows it can be.

“We’ve lost a lot,” she said.

Across town at the Jackson Medical Mall, candidate Tim Henderson gathered with members of his family and volunteers around 7:30 p.m. while the election results trickled in.

Henderson, a military consultant who went from little name recognition to finishing third in the primary, said people liked him precisely because he was an outsider, having moved back to the city just two years ago.

“We keep electing the politicians that have been around, and we keep getting the same thing,” he said.

Inside the mall, also a voting location, the poll workers were packing up the precinct. In the center of the mall, empty tables and chairs waited for Henderson’s supporters who were steadily showing up for the watch party. Slow jazz music was playing.

Henderson set up his campaign headquarters here in an office he also uses for his consulting business. Since it was close to a precinct, he had to take down his office signage.

But the retired Air Force lieutenant colonel said he would stand outside the medical mall and talk to potential voters as they walked in, including one woman whose mother was killed in a shooting earlier this year.

“People are tired in this city,” he said.

That was reflected in the city’s anemic turnout, he added. At the medical mall, for instance, officials recorded just 115 official votes from the 541, as of 2024, registered there.

“When people have been in such a depressed and distressed state for so long psychologically it impacts them,” he said.

As he spoke to a reporter in his campaign office, someone called his desk phone. “Please, Mayor Henderson, give me a call back,” they said, but Henderson couldn’t answer it in time.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days agoSevere storms will impact Alabama this weekend. Damaging winds, hail, and a tornado threat are al…

-

Mississippi Today16 hours ago

Mississippi Today16 hours agoPharmacy benefit manager reform likely dead

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days agoUniversity of Alabama student detained by ICE moved to Louisiana

-

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed7 days agoSeafood testers find Shreveport restaurants deceiving customers with foreign shrimp

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed4 days agoTornado watch, severe thunderstorm warnings issued for Oklahoma

-

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed7 days agoRoane County Schools installing security film on windows to protect students

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Virginia News Feed5 days agoYoungkin removes Ellis, appoints Cuccinelli to UVa board | Virginia

-

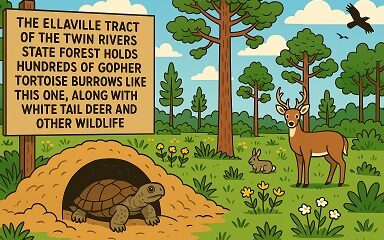

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days agoPeanut farmer wants Florida water agency to swap forest land