Mississippi Today

Mississippi remains an outlier in jailing people with serious mental illness without charges

This article contains descriptions of threats of violence and mental illness. If you or someone you know needs help:

- Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 988

- Text the Crisis Text Line from anywhere in the U.S. to reach a crisis counselor: 741741

This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with Mississippi Today. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

Nearly 40 years ago, a federal appeals court ruled that Alabama officials could not jail people in mental health crisis who were sent to the state for help. Jailing people going through the state’s civil commitment process, the court decided, amounted to punishment. And about 30 years ago, after Kentucky was labeled the worst state in the nation for jailing mentally ill people without charges, legislators there banned it.

But a new survey of counties and an analysis of jail dockets in Mississippi, which has no such law, has found that people going through the civil commitment process for mental illness are regularly jailed as they await evaluation and treatment, even when they haven’t been charged with a crime. Some counties routinely hold such people in jail — people awaiting treatment for mental illness or substance abuse were held in jail without charges at least 2,000 times from 2019 to 2022 in 19 counties alone, sometimes for days or weeks.

Nationally, Mississippi is a stark outlier. Mississippi Today and ProPublica conducted a nationwide survey of disability advocacy organizations and state agencies that oversee behavioral health. None described anything close to the scale of what’s happening in Mississippi.

Civil commitment laws are meant to ensure people get treatment even when they don’t recognize that they need it, said James Tucker, an attorney and the director of the Alabama Disabilities Advocacy Program. Locking them up as they wait for a treatment bed doesn’t fulfill that goal.

“The bargain for your lack of freedom is that the state has decided you need treatment,” he said. “The minute that order is entered, the state has a constitutional duty to deliver treatment.”

At least 12 states plus the District of Columbia prohibit jailing people undergoing commitment proceedings for mental illness unless they have been charged with a crime.

Mississippi law, however, allows people going through the civil commitment process to be sent to jail if there is “no reasonable alternative.” If there are no publicly funded beds in appropriate facilities, local officials sometimes decide they have no other option.

“We Forbid the Use of Jails”

In the 1970s, a federal class-action lawsuit against Alabama officials alleged that it was unconstitutional to jail people going through the commitment process for mental illness while they awaited hearings. It was common at the time: Probate judges in three-quarters of the state’s counties had jailed people, according to discovery findings cited in a court ruling.

Lawyers for the plaintiffs — everyone in the state who had been committed or would be in the future — cited previous lawsuits that had uncovered fire hazards, overcrowding and a dearth of mental health and routine medical care in Alabama’s county jails.

The district court ruled against the plaintiffs’ constitutional claims, reasoning that if the local jail was the only option in a county, it was the least restrictive facility that would also protect society.

“The bargain for your lack of freedom is that the state has decided you need treatment. The minute that order is entered, the state has a constitutional duty to deliver treatment.”

James Tucker, director of the Alabama Disabilities Advocacy Program

But in 1984, a panel of judges on the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals rejected that reasoning. Circuit Judge Thomas Alonzo Clark wrote in his opinion that nothing prevented counties from placing people in a public facility in another county or in a local private facility that was equipped to handle mentally ill patients.

Clark cited a doctor’s testimony that jail often worsened psychosis, made it harder to treat people and increased suicidal tendencies.

“We forbid the use of jails for the purpose of detaining persons awaiting involuntary civil commitment proceedings, finding that to do so violates those persons’ substantive and procedural due process rights,” the judge wrote.

The reasons that Alabama officials provided for placing people in jail were similar to Mississippi officials’ arguments today. But Mississippi is in a different federal circuit, and the practice there has not been tested with a class-action lawsuit.

A sister of one woman who had died in a Mississippi jail in 1987 tried and failed to convince a federal judge that the woman’s rights had been violated when she was incarcerated without treatment.

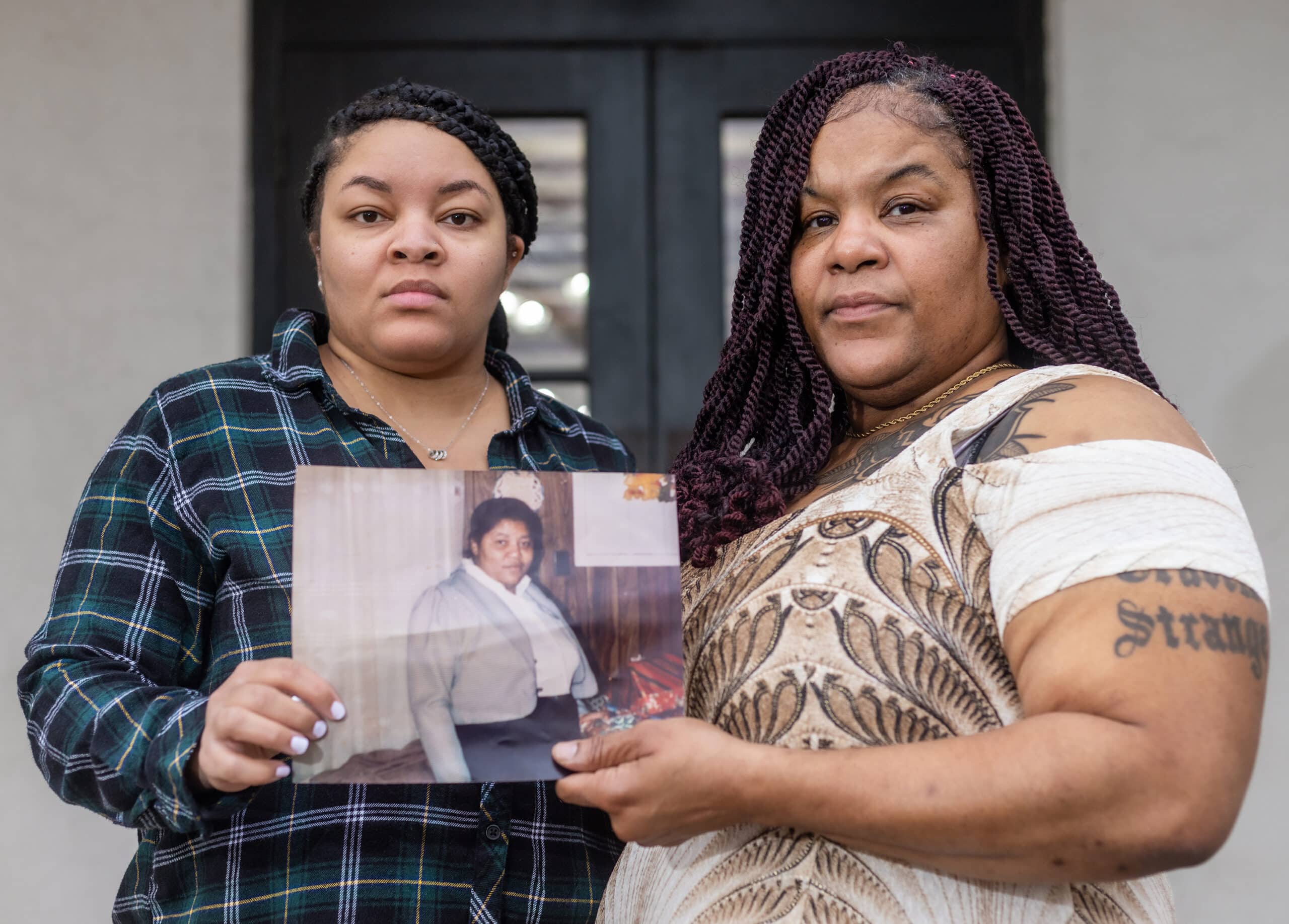

Mae Evelyn Boston, an Oxford woman who had dealt with paranoid schizophrenia for most of her adult life, had a psychotic episode shortly after giving birth. Her older daughter, Everlean, was 12 years old; she remembers her mother saying she was going to kill the baby because the girl “had a demon in her.”

One of Boston’s sisters initiated commitment proceedings — making Boston one of more than 100 people jailed for that reason from 1984 to 1988 in Lafayette County, according to a deposition cited in a 1990 ruling by U.S. District Judge Neal Biggers. When deputies arrived to take her mother into custody for evaluation, Everlean recalled, it took six of them to get her onto the ground before handcuffing her and placing her in the back of a cop car.

Once Boston was in jail, guards did not complete a medical screening required by department policy and didn’t know Boston had given birth via cesarean section 12 days before, Biggers wrote. She died two days later from heart failure caused by blood clots.

Everlean Boston remembers her mother smoking cigarettes and listening to the blues on quiet Sundays at home. The day deputies took her mother away was the last time she saw her. “I never got to say goodbye,” she recalled. “I never got to say I loved her. It hurts.”

“I never got to say goodbye. I never got to say I loved her. It hurts.”

Everlean Boston, whose mother, Mae Evelyn Boston, died in jail as she went through the civil commitment process

Biggers concluded that the “medical care customarily provided by the county for mentally ill detainees does not fall below constitutional standards” and that what happened with Boston represented a “scheduling error” and an “isolated instance.” The county, which argued it had provided adequate care for Boston, had the right to detain people like her “in the interest of societal safety,” he found, and those people were not entitled to placement in the “least restrictive alternative” such as a hospital. Biggers considered the Alabama appeals court ruling from a few years earlier, but concluded it didn’t apply because it was based on specific facts about that state’s jails.

“The court declines to hold that use of jails for temporary detention of persons awaiting civil commitment proceedings is unconstitutional per se,” Biggers ruled.

Since then, at least nine lawsuits have been filed over the deaths of Mississippians incarcerated during civil commitment proceedings. None of those lawsuits directly challenged the constitutionality of being jailed during the commitment process. The U.S. Supreme Court has not ruled on the matter, academics and attorneys with expertise in civil commitment said.

In the years after Boston’s death, Mississippi continued to stand out.

In 1992, the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill and Public Citizen’s Health Research Group conducted a national survey about the practice of jailing mentally ill people.

Almost a third of city and county jails in Mississippi responded. About 76% of respondents said they detained people who had not been charged with a crime and were awaiting an evaluation, treatment or hospitalization for mental illness. That was the second-highest percentage of any state in the country and far higher than the national average of 29%.

An unnamed Mississippi jail official said in the organizations’ report that jails were a “dumping ground for what nobody else wants.”

The report gave its “Worst State Award” to Kentucky, where 81% of responding jails reported holding people without criminal charges for mental evaluations.

Two years later, Kentucky’s legislature voted unanimously to ban the practice. The state health agency and its federally designated disability rights organization told Mississippi Today and ProPublica that Kentucky jails today are not used to hold people without charges awaiting mental health evaluations.

Few States Compare to Mississippi

Officials with the Mississippi Department of Mental Health emphasize that they do not support the practice of jailing people during the commitment process. But a spokesperson said they “have heard anecdotally from other states regarding challenges of individuals waiting in jail.”

Nationally, even basic data like the number of people committed each year is elusive. After reviewing some of Mississippi Today and ProPublica’s findings, the Treatment Advocacy Center, a national nonprofit that advocates making it easier for people with mental illness to get treatment, started planning a project to understand how often people are jailed without charges during the commitment process across the U.S.

Mississippi Today and ProPublica contacted agencies overseeing mental health and disability advocacy organizations in every state to find out whether Mississippi is an outlier. It is.

Respondents in 42 states and the District of Columbia said they were not aware of people being regularly held in jail without charges during the psychiatric civil commitment process. In a handful of those states, respondents said they had seen it once or twice over the years.

In two states, people can be sent from state psychiatric hospitals to mental health units inside prisons. In a few others, respondents said they had seen people jailed for noncompliance with court-ordered treatment for mental illness or substance abuse.

Respondents in three other states — Alaska, South Dakota and Wyoming — reported that people sometimes are sent to jail to await psychiatric evaluations, but the information they provided suggested that it happens to fewer people, and for a shorter period, than in Mississippi.

In 2018, staffing shortages at the Alaska Psychiatric Institute caused people to be held at the Anchorage Correctional Complex until they could be evaluated. The next year, an Anchorage judge ordered an end to the practice except in the “rarest circumstances,” finding that it had caused “irreparable harm.”

A subsequent settlement declared that jails shouldn’t be used unless no other option was available and that such detentions should be as short as possible.

But detentions do still occasionally happen in the state when people in rural areas await transportation to an evaluation center, said Mark Regan, legal director at the Disability Law Center of Alaska. According to the Alaska Department of Family and Community Services, people awaiting evaluation were held in jail 555 times from mid-2018 through late February 2023.

Across South Dakota, people without charges sometimes have been held in jail during the commitment process, according to law enforcement agencies and Disability Rights South Dakota, but such holds are limited by law to 24 hours; in Mississippi, the vast majority of cases analyzed were for more than 24 hours. The South Dakota Department of Social Services said it doesn’t track how often it happens and declined to answer questions.

And in Wyoming, a person can be held in jail for up to 72 hours on an emergency basis before a hearing, but they must have a mental examination within 24 hours. Such holds in jail have occurred “in very rare circumstances,” according to the state.

Attempts to constrain the use of jails date back at least to 1950, when the federal government sent governors model legislation that limited the incarceration of people for mental illness to “extreme emergency” situations. The National Institute of Mental Health called incarcerating such people “among the worst of current practices.”

Some states adopted the legislation. Mississippi did not.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Pharmacy benefit manager reform likely dead

Hotly contested legislation that aimed to increase the transparency and regulation of pharmacy benefit managers appeared dead in the water Tuesday after a lawmaker challenged the bill for a rule violation.

The bill was sent back to conference after Rep. John Hines, D-Greenville, raised a point of order challenging the addition of code sections to the bill, which will likely kill it.

House members in the past have chosen to turn a blind eye to the rule, which would require the added code sections to be removed when the bill is returned to conference. This fatal flaw will make it difficult to revive the legislation.

“It will almost certainly die,” said House Speaker Jason White, who authored the legislation. “And you can celebrate that with your pharmacist when you see them.”

“…This wasn’t ‘gotcha.’ Everybody in this chamber knew that code sections were added, because the attempt was to make 1123 more suitable to all the parties.”

The bill sought to protect patients and independent pharmacists, who have warned that if legislators do not pass a law this year to regulate pharmacy benefit managers, which serve as middlemen in the pharmaceutical industry, some pharmacies may be forced to close. They say that the companies’ low payments and unfair business practices have left them struggling to break even.

The bill underwent several revisions in the House and Senate before reaching its most recent form, which independent pharmacists say has watered the bill down and will not offer them adequate protection.

House Bill 1123, authored by White, originally focused on the transparency of pharmacy benefit managers. The Senate then beefed up the bill by adding provisions barring the companies from steering patients to affiliate pharmacies and prohibiting spread pricing – the practice of paying insurers more for drugs than pharmacists in order to inflate pharmacy benefit managers’ profits.

Independent pharmacists, who have flocked to the Capitol to advocate for reform this session, widely supported the Senate’s version of the bill.

The Senate incorporated several recommendations from the House into its bill, saying that they believed that the legislation would have the House’s support.

Instead, the House sent the bill to conference and requested additional changes, including new language that would eliminate self-funded insurance plans, or health plans in which employers assume the financial risk of covering employees’ health care costs themselves, from a section of the bill that prohibits pharmacy benefit managers from steering patients to specific pharmacies.

This language seeks to satisfy employers, who argue that regulating pharmacy benefit managers’ business practices will lead to higher health insurance costs.

Sen. Rita Parks, R-Corinth, who has spearheaded pharmacy benefit manager reform efforts in the Senate, previously said that adding the language to the bill would “remove any protection out of the law.” But she signed the conference report that included the language Monday after a heated conference meeting between lawmakers.

Rep. Hank Zuber, R-Ocean Springs and co-author of the bill, said the bill has something for everybody, gesturing to its concessions for employers and independent pharmacists. He said the bill gives independent pharmacists 85% of what they wanted.

Mississippi Independent Pharmacies Association director Robert Dozier was not available for comment by the time the story published.

Zuber told House members Tuesday to “blame the Senate” for the slow progress of pharmacy benefit manager reform in Mississippi, citing the body’s failure to take up a drug pricing transparency bill half a decade ago, for three years in a row.

“If the Senate had followed the leadership and the legislation that we drafted those many years ago, we would not be here,” Zuber said. “We would have the information on drug pricing, we would have the information and transparency on (pharmacy benefit managers) and we would have the ultimate reason as to why drug costs continue to rise.”

Members of the House expressed dissatisfaction with the legislation Tuesday, arguing it did not do enough to ensure lower prescription drug costs for consumers.

“I’m going to try to do something next year that goes even further,” Zuber responded.

For the past several years, lawmakers have proposed bills to regulate pharmacy benefit managers, but none have made it as far as this session.

“We’ll go another year,” said White.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

Feuding GOP lawmakers prepare to leave Jackson without a budget, let governor force them back

After months of bitter Republican political infighting, the Legislature appears likely to end its session Wednesday without passing a $7 billion budget to fund state agencies, potentially threatening a government shutdown if they don’t come back and adopt one by June 30.

After the House adjourned Tuesday night, Speaker Jason White said he had presented the Senate with a final offer to extend the session, which would give the two chambers more time to negotiate a budget. As for now, the 100 or so bills that make up the state budget are dead.

The Senate leadership was expected to meet and consider the offer Tuesday evening, White said. But numerous senators both Republican and Democrat said they would oppose such a parliamentary resolution, and Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann has also said it’s unlikely and that the governor will have to force lawmakers back into special session.

White said he believes, if the Senate would agree to extend the session and restart negotiations, lawmakers could pass a budget and end the 2025 session by Sunday, only a few days later than planned.

But if the Senate chooses not to pass a resolution extending the session, White said the House would end the session on Wednesday.

It would take a two-thirds vote of support in both chambers to suspend the rules and extend the session. The Senate opposition appears to be enough to prevent that.

Still, the speaker said he believes Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann and Senate leaders are considering the proposal. But he said if he doesn’t hear a positive response by Wednesday, the House will adjourn and wait for Gov. Tate Reeves to call a special session at a later date.

“We are open to (extending the session), but we will not stay here until Sunday waiting around to see if they might do it,” White said.

White said leaving the Capitol without a budget and punting the issue to a special session might not cool tensions between the chambers, as some lawmakers hope.

“I think when you leave here and you end up in a special session, some folks say, ‘Well everybody that’s upset will cool down by then.’ They may, or it may get worse. It may shine a different and specific light on some of the things in this budget and the differences in the House and Senate,” White said. “Whereas, I think everybody now is in the legislative mode, and we might get there.”

The Mississippi Constitution does not grant the governor much power, but if Gov. Tate Reeves calls lawmakers into a special session, he gets to set the specific legislative agenda — not lawmakers.

White said the governor could potentially use his executive authority to direct lawmakers to take up other bills, such as those related to education, before getting to the budget.

“When we leave here without a budget, it is entirely the governor’s prerogative to when he (sets a special session) and how he does that.”

While the future of the state’s budget hangs in the balance, lawmakers have spent the remaining days of their regular session trying to pass the few remaining bills that remained alive on their calendars.

House approves DEI ban, Senate could follow suit on Wednesday

The House on Tuesday passed a proposal to ban diversity, equity and inclusion programs from public schools, and both chambers approved a measure to establish a form of early voting.

The House approved a conference report compromise to ban DEI programs and a list of “divisive concepts” from K-12 schools, community colleges and universities. If the Senate follows suit, Mississippi would join a number of other Republican-controlled states and President Donald Trump, who has made rooting DEI out of the federal government one of his top priorities.

The agreement between the Republican-dominated chambers follows hours of heated debate in which Democrats, all almost of whom are Black, excoriated the legislation as a setback in the long struggle to make Mississippi a fairer place for minorities. Legislative Republicans argued the legislation will elevate merit in education and remove from school settings “divisive concepts” that exacerbate divisions among different identity groups.

The concepts that will be rooted out from curricula include the idea that gender identity can be a “subjective sense of self, disconnected from biological reality.” The move reflects another effort to align with the Trump administration, which has declared via executive order that there are only two sexes.

The House and Senate disagreed on how to enforce the act, but ultimately settled on an agreement that would empower students, faculty members and contractors to sue schools for violating the law, but only after they go through an internal campus review process that would give schools time to make changes. The legislation could also withhold state funds from schools that don’t comply.

Legislature sends ‘early voting lite’ bill to governor

The Legislature also overwhelmingly passed a proposal to establish a watered down version of early voting, though the legislation is titled “in-person excused voting,” and not early voting.

The proposal establishes 22 days of in-person voting before Election Day that requires voters to go to the circuit clerk’s office or another location county officials have designated as a secure early voting facility, such as a courtroom or a board of supervisors meeting room.

To cast an early vote, someone must present a valid form of photo ID and list one of about 15 legal excuses to vote before Election Day. The excuses, however, are broad and would, in theory, allow many people to cast early ballots.

Examples of valid excuses are voters expecting to work on Election Day, being at least 65 years old, being currently enrolled in college or potentially travelling outside of their county on Election Day.

Since most eligible voters either work, go to college or are older than 65 years of age, these excuses would apply to almost everyone.

“Even though this isn’t early voting as we saw originally, it makes this more convenient for hard working Mississippians to go by their clerks’ office and vote in person after showing an ID 22 days prior to an election,” Senate Elections Chairman Jeremy England said.

Republican Gov. Tate Reeves opposes early voting, so it’s unclear if he would sign the measure into law or veto it.

Both chambers are expected to gavel at 10 a.m. on Wednesday to debate the final items on their agenda.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

‘A lot of us are confused’: Lacking info, some Jacksonians go to wrong polling place

Johnny Byrd knew that when his south Jackson neighborhood Carriage Hills changed wards during redistricting last year, his neighbors would have trouble finding their correct polling place on Election Day.

So he bought a poster board and inscribed it with their new voting location – Christ Tabernacle Church.

“I made a sign and placed it in front of the entrance to our neighborhood that told them exactly where to go so there would be no confusion,” said Byrd, vice president of the Association of South Jackson Neighborhoods.

Still, on April 1, a car full of voters from a senior living facility who should have gone to Christ Tabernacle were driven to their old polling place.

“I thought it was unfortunate they had to get there and find out rather than knowing in advance that their polling location was different,” said Sen. Sollie Norwood, a Democrat from Jackson who was on the ground Tuesday helping constituents with voting.

One of those elderly women became frustrated and said she no longer wanted to vote, Norwood said, though her companions tried to convince her otherwise. By midday Tuesday, 300 people had voted at Christ Tabernacle, one of the city’s largest precincts currently in terms of registered voters, but among the lowest in turnout historically.

Voting rights advocates and candidates vying for municipal office in Jackson are keeping an eye on issues facing voters at the polls, though without official results, it remains to be seen if that will dampen turnout this election with the hotly contested Democratic primary.

“I still believed it was gonna be low,” Monica McInnis, a program manager for the nonprofit OneVoice, said of turnout. “I was expecting it would be a little higher because of what is on the ballot and how many people are running in all of the wards as well as the mayor’s race.”

The situation is evolving as the day goes on, but the main issues are twofold. One, thousands of Jackson voters have new precinct locations after redistricting last year put them into a new city council ward.

Two, some voters didn’t realize their polling place for the municipal elections may differ from where they voted in last year’s national elections, which are run by the counties.

In Mississippi, voters are assigned two precincts that are often but not always the same: A municipal location for city elections and a county location for senate, gubernatorial and presidential elections

“People in Mississippi, we go to the same polling location for three years, and that fourth year, it changes,” said Jada Barnes, an organizer with the Jackson-based nonprofit MS Votes. “A lot of us are confused. When people are going to the polling place today, they’re seeing it is closed, so they’re just going back home which is making turnout go even lower.”

Barnes said she’s hearing this primarily from a few Jackson voters who called a hotline that MS Votes is manning. Lack of awareness around polling locations is a big deterrent, she said, because most people are trying to squeeze their vote in between work, school or family responsibilities.

“Maybe you’re on your lunch break, you only got 30 minutes to go vote, you learn that your polling location has changed and now you have to go back to work,” she said.

Norwood said he heard from a group of students assigned to vote at Christ Tabernacle who had attempted to vote at the wrong precinct and were told their names weren’t on the rolls. They didn’t know they had been moved from Ward 4 to Ward 6, Norwood said, meaning they expected to vote in a different council race until reaching the polls Tuesday.

Though voters have a duty to be informed of their polling location, Barnes said city and circuit clerks and local election commissioners are ultimately responsible for making sure voters know where to go on Election Day.

Angela Harris, the Jackson municipal clerk, said her office worked to inform voters by mailing out thousands of letters to Jacksonians whose precincts changed, including the roughly 6,000 whose wards changed during the 2024 redistricting.

“I am over-swamped,” she said yesterday.

Despite her efforts, at least one voter said he never got a letter. Stephen Brown learned through Facebook, not an official notice, that he was moved from Ward 1 to Ward 2.

A resident of the Briarwood Heights neighborhood in northeast Jackson, Brown’s efforts to vote Tuesday have been complicated by mixed messages and a lack of communication. He has yet to vote, even though he showed up at the polls at 7:10 this morning.

His odyssey took him to two wrong locations, where the poll managers instructed Brown to call his ward’s election commissioner, who did not answer multiple calls, Brown said. Brown finally learned through a Facebook comment that he could look up his new precinct on the Mississippi Secretary of State’s website — if he scrolled down the page past his county precinct information.

This afternoon, Brown has a series of meetings planned, so now he’s hoping for a 30-minute window to try voting one more time, even though he’s skeptical it will make a difference.

“I’m a very disenchanted voter, because I’ve been let down so much,” he said. “I vote because it’s the thing that I’m supposed to do and because of the sacrifices of my ancestors, but not because I truly believe in it, you know?”

Brown’s not alone in facing turbulence. Back at Christ Tabernacle, one Jackson voter, who declined to give her name, said she’s frustrated from having to drive to three polling locations in one day.

“I’m dissatisfied with the fact that I had to drive from one end of this street and all of the back to come over here when I usually vote over here on Highway 18,” she said. “This was a great inconvenience, gas wise and time wise.”

The same thing happened to Rodney Miller. He called the confusion some voters are facing in this election “unnecessary.”

“That ain’t the way we should be handling business,” he said. “We should be looking out for one another better than that, you know? It’s already enough getting people out to vote, and when you confuse them when they try? Come on now. That’s discouraging.”

Christ Tabernacle is the second largest precinct in the city in terms of registered voters, with 3,330 assigned to vote there as of 2024, according to documents retrieved from the municipal election committee. But it had one of the lowest voter turnout rates – 10% in the 2021 primary election before redistricting and before it became so large.

Byrd mentioned the much higher turnout in places like Ward 1 in northeast Jackson, compared to where he lives in south Jackson. Why does Byrd think this is?

“Civics,” Byrd said. “They took civics out of school. If you ask the average person what is the role and responsibility of any elected official, they can’t tell you.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days agoFamily mourns death of 10-year-old Xavier Williams

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days agoSevere storms will impact Alabama this weekend. Damaging winds, hail, and a tornado threat are al…

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed4 days agoUniversity of Alabama student detained by ICE moved to Louisiana

-

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed6 days agoSeafood testers find Shreveport restaurants deceiving customers with foreign shrimp

-

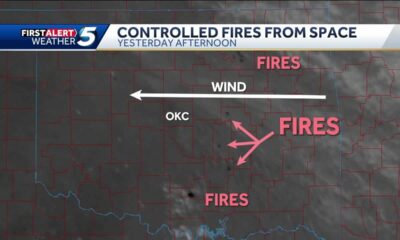

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed3 days ago

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed3 days agoTornado watch, severe thunderstorm warnings issued for Oklahoma

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed7 days agoWhy are Oklahomans smelling smoke Wednesday morning?

-

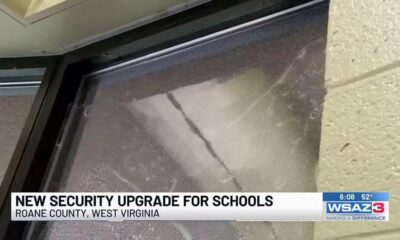

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed6 days agoRoane County Schools installing security film on windows to protect students

-

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed7 days agoStudents in Monroe County Schools are ready to shoot their way to the WV State Archery Championships