Mississippi Today

Their families said they needed treatment. Mississippi officials threw them in jail without charges.

This article contains detailed descriptions of mental illness and suicide. If you or someone you know needs help:

- Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 988

- Text the Crisis Text Line from anywhere in the U.S. to reach a crisis counselor: 741741

This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with Mississippi Today. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

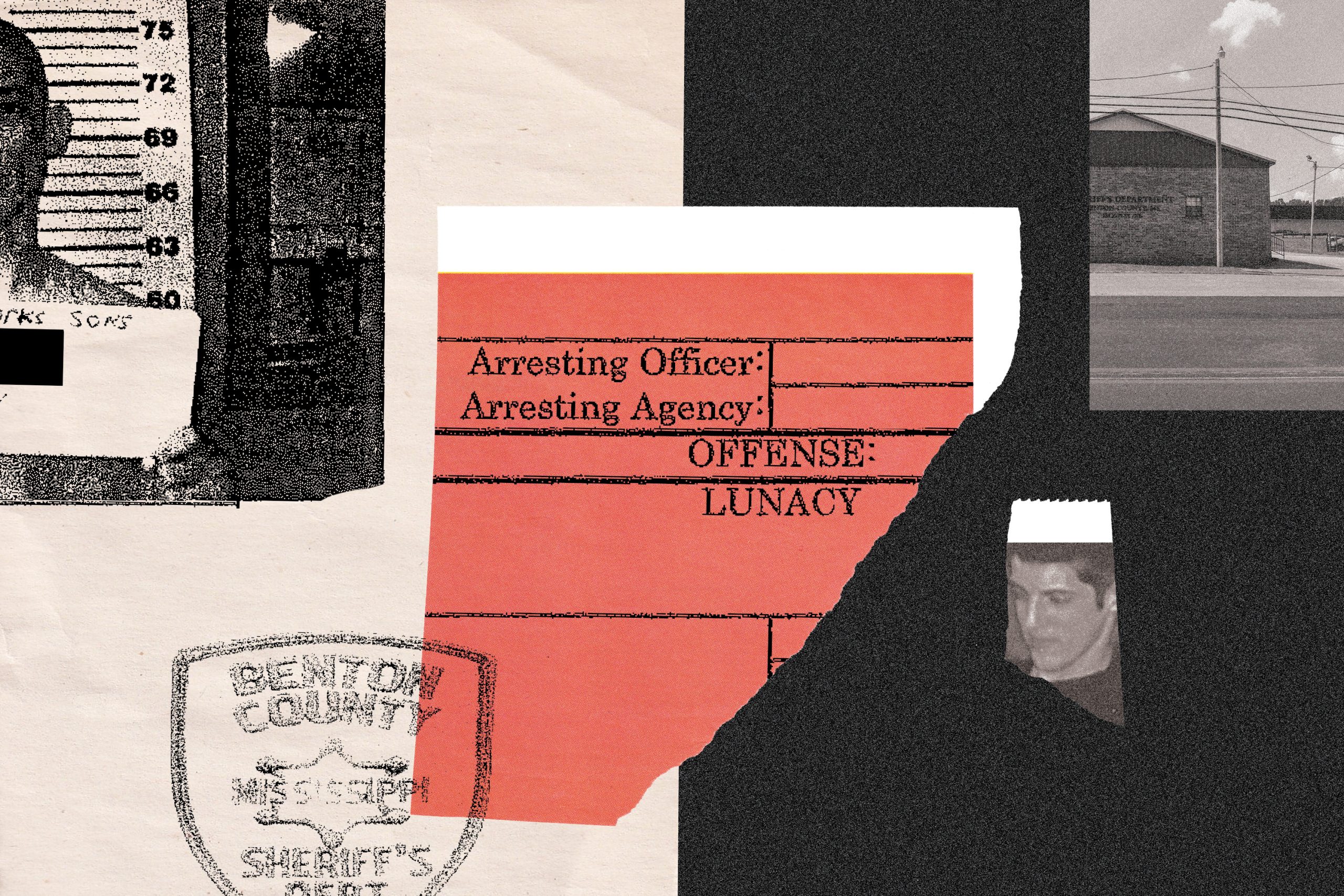

When sheriff’s department staff in Mississippi’s Benton County took Jimmy Sons into custody several years ago, they followed their standard protocol for people charged with a crime: They took his mug shot, fingerprinted him, had him change into an orange jumpsuit and locked him up.

But Sons, who was then 20 years old, had not been charged with a crime. Earlier that day, his father, James Sons, had gone to a county office to ask that his youngest son be taken in for a mental evaluation and treatment. Jimmy Sons had threatened to hurt family members and himself, and his father had come across him sitting on his bed with a loaded shotgun.

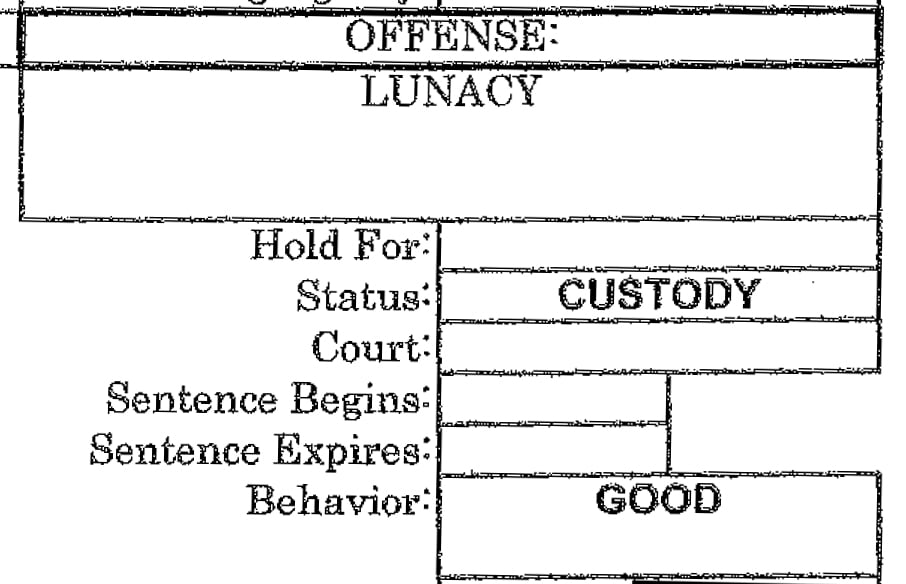

On Sons’ booking form, in the spot where jailers usually record criminal charges, was a single word: “LUNACY.”

In every state, people who present a threat to themselves or others can be ordered to receive mental health treatment. Most states allow people with substance abuse problems to be ordered into treatment, too. The process is called civil commitment.

But Mississippi Today and ProPublica could not find any state other than Mississippi where people are routinely jailed without charges for days or weeks during that process.

What happened to Sons has occurred hundreds of times a year in the state.

The news organizations examined jail dockets from 19 Mississippi counties — about a quarter of the state’s 82 — that clearly marked bookings related to civil commitments. All told, people in those counties were jailed at least 2,000 times for civil commitments alone from 2019 to 2022. None had been charged with a crime.

Most were deemed to need psychiatric treatment; others were sent to substance abuse programs, according to county officials.

Since 2006, at least 13 people have died in Mississippi county jails as they awaited treatment for mental illness or substance abuse, Mississippi Today and ProPublica found. Nine of the 13 killed themselves. At least 10 hadn’t been charged with a crime.

We shared our findings with disability rights advocates, mental health officials in other states and 10 national experts on civil commitment or mental health care in jails. They used words such as “horrifying,” “breaks my heart” and “speechless” when they learned how many people are jailed in Mississippi as they go through the civil commitment process.

Some said they didn’t see how it could be constitutional.

“If an ER is full, you don’t send people to jail,” said Megan Schuller, legal director of the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, a Washington, D.C.-based organization. “This is just outright discriminatory treatment in my view.”

Mississippi Today and ProPublica also interviewed 10 individuals who had been committed and jailed, as well as 20 family members.

Many of those people said they or their family members had been housed alongside criminal defendants. Nobody knew how long they would be there. They were often shackled when they left their cells. Some of them said they couldn’t access prescribed psychiatric medications or had minimal medical care as they experienced withdrawal from illegal drugs.

“It felt more criminal than, like, they were trying to help me,” said Richard Millwood, who was booked into the DeSoto County jail in 2020 following an attempted suicide. “I got the exact same treatment in there as I did when I was in jail facing charges. In fact worse, in my opinion, because at least when I was facing charges I could bond out.”

“I got the exact same treatment in there as I did when I was in jail facing charges. In fact worse, in my opinion, because at least when I was facing charges I could bond out.”

Richard Millwood, who was booked into jail following an attempted suicide

DeSoto County leadership, informed of Millwood’s statement, did not respond.

Millwood spent 35 days in jail before being admitted to a publicly funded rehab program 90 miles away.

Jimmy Sons didn’t receive a mental evaluation when he was booked into the Benton County jail in September 2015, according to documents in a lawsuit his father later filed. Less than 24 hours later, he was dead. Left alone in a cell without regular visits by jail staff, he had hanged himself.

He had been back in Mississippi for just a few days, planning to join his dad in electrical work, said his mother, Juli Murray. He had set out from her home in Bradenton, Florida, so early in the morning that he didn’t say goodbye.

Murray remembers the phone call from Jimmy’s half-brother in which she learned her son was in jail. She didn’t understand why.

“If you do something wrong, that’s why you’re in jail,” she said. “Not if you’re not mentally well. Why would they put them in there?”

The Lesser Sin

When James Sons went to the clerk’s office in the tiny town of Ashland to file commitment paperwork for his son, he took the first step in Mississippi’s peculiar, antiquated system for mandating treatment for people with serious mental health problems.

It starts when someone — usually a family member, but it could be almost anyone — signs a form alleging that the person in question is “in need of treatment because the person is mentally ill under law and poses a likelihood of physical harm to themselves or others.”

James Sons filled out that form, listing why he was concerned: Jimmy’s guns, his threats, his talk of suicide.

Then a special master — an attorney appointed by a chancery judge to make commitment decisions — issued a “Writ to Take Custody.” It instructed sheriff’s deputies in Benton County, just south of the Tennessee border, to hold Jimmy Sons at the jail until he could be evaluated.

The sheriff’s office asked Sons to come in on an unrelated matter. When he showed up, Chief Deputy Joe Batts told him he needed a mental health evaluation. Batts tried to reassure Sons that the process would be as quick as possible and would end with him back home, according to Batts’ testimony in the lawsuit Sons’ father filed over his death.

Then Batts told Sons, “What we’re going to have to do now is take you back and book you.”

What he never told Sons, he later acknowledged in a deposition, was that the young man would have to wait in jail for days before he would see a mental health provider. The first screening required by law was four days away. If it concluded he needed further examination, he would be evaluated by two more medical professionals. Then the special master would decide whether to order him into treatment at a state psychiatric hospital.

The whole process should take seven to 10 days, according to the state Department of Mental Health. But sometimes it takes longer, the news organizations found. And if someone is ordered into treatment at their hearing, they generally have to wait for a bed, though the department says average wait times for state hospital beds after hearings have dropped dramatically in the last year.

While waiting for their hearing, people like Sons are supposed to receive treatment at a hospital or a short-term public mental health facility called a crisis stabilization unit. But state law does allow people to be jailed before their commitment hearing if there is “no reasonable alternative.” (The law is less clear about what’s allowed following a hearing.)

Mississippi Today and ProPublica spoke to dozens of officials across Mississippi involved in the commitment process: clerks who handle the paperwork, chancery judges and special masters who sign commitment orders, sheriffs who run the jails, deputies who drive people from jails to state hospitals, and the head of the state Department of Mental Health.

None of them thinks jail is the right place for people awaiting treatment for mental illness.

“We’re not a mental health hospital,” said Greg Pollan, president of the Mississippi Sheriffs’ Association and the sheriff of rural Calhoun County in the north of the state. “We’re not even a mental health Band-Aid station. That’s not what we do. So they should never, ever see the inside of my jail.”

Batts himself, who took Sons into custody in Benton County, said law enforcement officers across Mississippi “hate to detain people like that. But we’re told we have to do it.” He acknowledged that the facility “was substandard to begin with, not having the space and the adequate facilities to hold and monitor someone in that mental state — it just puts everybody in a bad situation.” And he said he thought the state could provide alternatives to jail.

Some counties jail most people going through the commitment process for mental illness, Mississippi Today and ProPublica found. Other counties reserve jail for people who are deemed violent or likely to hurt themselves. And at least a handful sometimes jail people committed for substance abuse — even though a 2021 opinion by the state’s attorney general says that isn’t allowed under state law.

This happens because until people are admitted to a state hospital, counties are responsible for covering the costs of the commitment process unless the state provides funding. If a crisis stabilization unit is full or turns someone away, the county must find an alternative, and it must foot the bill.

Counties can place patients in an ER or contract with a psychiatric hospital — and some do — but many officials balk at the cost. Many officials, particularly those in poor, rural counties, see jail as the only option.

“You have to put them somewhere to monitor them,” said Cindy Austin, chancery clerk in rural Smith County, located in central Mississippi. Chancery clerks are responsible for finding beds for people going through the commitment process. “It’s not that anybody wants to hold them in jail, it’s just we have no hospital here to hold them in.”

Timothy Gowan, an attorney who adjudicated commitments in Noxubee County from 1999 to late 2020, said people going through the commitment process there generally were jailed if they were determined to be violent and their family didn’t want them at home.

According to the Noxubee County jail docket, people going through the civil commitment process with no criminal charges were booked into the jail about 50 times from 2019 to 2022. Ten stays lasted at least 30 days. The longest was 82 days.

“Putting a sick person in a jail is a sin,” Gowan said. “But it’s the lesser of somebody getting killed.”

Some counties rarely hold people in jail — sometimes because a sheriff, chancery judge or other official has taken a stand against it. Rural Neshoba County in central Mississippi pays Alliance, a psychiatric hospital in Meridian, to house patients.

“We’re not a mental health hospital. We’re not even a mental health Band-Aid station. That’s not what we do. So they should never, ever see the inside of my jail.”

Greg Pollan, president of the Mississippi Sheriffs’ Association and sheriff of Calhoun County

The practice isn’t confined to poor, rural counties. DeSoto County, a populous, relatively wealthy county near Memphis, jailed people without charges about 500 times over four years, the most of any of the counties analyzed by Mississippi Today and ProPublica. The median jail stay there was about nine days; the longest was 106.

The state and county recently set aside money to build a crisis stabilization unit — currently, the nearest one is about 40 miles away — but the county and the local community mental health center haven’t decided on a location, said County Supervisor Mark Gardner.

Some county officials say that keeping people out of jail during the process requires the state to step up. State Rep. Jansen Owen, a Republican from Pearl River County in southern Mississippi who represents people during the commitment process, said he believes counties that spend “millions of dollars on fairgrounds and ballparks” could find alternatives to jail. But he also sees a need for more state-funded facilities.

“You can’t just throw it on the counties,” he said. “It’s a state prerogative. And them being held in the jail, I think, is a result of the state kicking the can down the road to the counties.”

Wendy Bailey, head of the state Department of Mental Health, said it’s “unacceptable” to jail people simply because they may need behavioral health treatment. Department staff have met with chancery clerks around the state to urge them to steer families away from commitment proceedings and toward outpatient services offered by community mental health centers whenever possible.

The Department of Mental Health says it prioritizes people waiting in jail when making admissions to state hospitals. The state has expanded the number of crisis unit beds from 128 in 2018 to 180 today, with plans to add more. And it has increased funding for local services in recent years in an effort to reduce commitments.

But Bailey said the department has no authority to force counties to change course, nor legal responsibility for people going through the commitment process until a judge orders them into treatment at a state psychiatric hospital.

Locked in the “Lunacy Zone”

Willie McNeese’s problems started after he came home to Shuqualak, Mississippi, a town of about 400 people and a lumber mill, in 2007. He had spent a decade in prison starting at age 17.

He found the changes that had taken place — bigger highways, cellphones — overwhelming, said his sister, Cassandra McNeese. He was eventually diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

“It’s like a switch — highs and lows,” said Willie McNeese, now 43. “I might have a whole lot of laughter going on, trying to make the next person laugh. Then my day going down, I be depressed and worried about situations that nobody can change but God.”

McNeese has been involuntarily committed in Noxubee County 10 times since 2008 and has been jailed during at least eight of them, one for more than a month in 2019 according to court records and the jail docket. During his most recent commitment starting in March 2022, McNeese was held in jail for a total of 58 days in two stints before eventually going to a state psychiatric hospital.

From 2019 to 2022, about 1,200 civil commitment jail stays in the 19 counties analyzed by Mississippi Today and ProPublica lasted longer than three days. That’s about how long it can take for people to start to experience withdrawal from a lack of psychiatric medications, which jails don’t always provide. About 130 stays lasted more than 30 days.

McNeese said he spent much of his time in jail last year standing near the door of his cell, what jail staff called the “Lunacy Zone,” screaming to be allowed to take a shower. A jailer tased him to quiet him down, and his clothes were taken from him. For a period, his mattress was taken, too.

“It’s a way of punishment,” he said. “They don’t handle it like the hospital. If you have a problem in the hospital they’ll come with a shot or something, but they don’t take your clothes or take your mattress or lock your door on you or nothing like that.”

McNeese said he had inconsistent access to medication and received none during his first stay in 2022, which lasted 25 days.

The Noxubee County Sheriff’s Department did not respond to questions about McNeese’s allegations.

Staff from Community Counseling, the community mental health center where McNeese had regular appointments, could have provided him with medication, but McNeese said no one from the center came to visit him in jail. A therapist at Community Counseling said staff go to the jail only when they’re called, usually when there’s a problem jail staff can’t handle. Rayfield Evins Jr., the organization’s executive director, said when he recently worked in Noxubee, deputies brought people from the jail to his facility for medication and treatment.

“If you have a problem in the hospital they’ll come with a shot or something, but they don’t take your clothes or take your mattress or lock your door on you or nothing like that.”

Willie B. McNeese, jailed multiple times following a diagnosis of bipolar disorder

Mental health advocates in Mississippi and other people who have been jailed during the commitment process said the limited mental health treatment McNeese received is common.

Mental health care varies widely from jail to jail, and no state agency sets requirements for what care must be provided. Jails can refuse to distribute medications that are controlled substances, which includes anti-anxiety medications like Xanax. The state Department of Mental Health says counties should work with community mental health centers to provide treatment to people waiting in jail as they go through the commitment process.

But those facilities generally don’t have the resources to provide services in jails, said Greta Martin, litigation director for Disability Rights Mississippi.

Martin’s organization, one of those charged by Congress with advocating for people with disabilities in each state, investigates county jails when it receives complaints. “We are not seeing any indication that these individuals are getting any mental health treatment while they are being held in these county facilities,” she said.

McNeese said those jail stays added physical discomfort and pain to the delusions that got him committed in the first place. “Then you get to the mental hospital — they have to straighten you all the way back over again,” he said.

Since being released from the state hospital last year, McNeese said, he has been doing well. He is now living in Cincinnati with his wife.

Scott Willoughby, the program director at South Mississippi State Hospital in Purvis, said it can be hard to earn patients’ trust when they arrive at the psychiatric hospital from jail.

At his facility, patients sleep two to a room in a hall decorated with photographs of nature scenes. Group counseling sessions are often held outside under a gazebo. In between, patients draw and paint during recreational therapy.

Willoughby has spoken with patients who had attempted suicide and were shocked to find themselves in jail as a result.

“People tend to associate jail with punishment, which is exactly the opposite of what a person needs when they’re in a mental health crisis,” he said. “Jail can be traumatic and stigmatizing.”

“I’m More Scared of Myself”

When Sons learned that he was going to be booked, he became anxious about being locked in a cell, Batts testified. So he was assigned to an area of the jail reserved for trusties — inmates who are allowed to work, sometimes outside the jail, while they serve their sentences.

On the afternoon of his first day in jail, Sons was sitting on his bed when a trusty named Donnie Richmond returned from work. Richmond said in a deposition that he asked a deputy who the new guy was.

“You better watch him,” Richmond recalled the deputy telling him. “He kind of off a little bit.”

Richmond offered Sons a cigarette and cookies and asked him why he was there. Sons took a cigarette and told Richmond the deputies had said he would hurt someone.

“He was like, ‘Man, I’m going to be honest with you,’” Richmond testified. “‘I ain’t going to hurt no one. I’m more scared of myself, of hurting myself.’”

Sons was not placed on suicide watch. The jail’s suicide prevention policy applied only to those who had attempted suicide in the jail, although attorneys for the jail officials in the lawsuit over his death said there was an unwritten policy to closely monitor people going through the commitment process.

That evening, Sons told a jailer he was feeling anxious around the other men. He asked to be moved to a cell by himself.

A guard took him to a cinder block cell with no windows. There was no television and nothing to read. He was given a blanket.

A security camera in Sons’ cell was supposed to allow jail staff to watch him at all times. But jail officials said in depositions that no one noticed anything unusual the next morning.

At 11:28 a.m., Sons rose from his bunk bed, walked to the door and placed his ear near it. He went back to his bunk, fashioned a noose and tied it around his neck. He sat there for three minutes before hanging himself, according to a narrative of the video in court records.

He stopped moving just before 11:38 a.m. A trusty serving lunch peeked through a tray opening in the door 48 minutes later and saw his body.

Sons’ father sued Benton County, the sheriff and several of his employees over his death. The defendants denied in court filings that they were responsible, but the county’s insurance company eventually settled the case for an undisclosed sum. (All that’s publicly known is that the county paid a $25,000 policy deductible toward defense costs.)

Sheriff’s department staff said in depositions they had kept an eye on Sons, but they couldn’t watch the video feed constantly. Lawyers for the defendants said there was no evidence sheriff’s department employees knew someone could kill himself in the way Sons did.

Sheriff A. A. McMullen, who is no longer in office, acknowledged in a deposition that “any mental commitment is a suicide risk,” but he said he wasn’t sure it would have made a difference if Sons had been placed on suicide watch.

“You could write up the biggest policy in the world and you couldn’t prevent it. There’s no way. God knows, you know, it hurts us,” he said. “If they’re going to do it, they’re going to do it.”

McMullen couldn’t be reached for comment for this story.

In an interview, jail administrator Kristy O’Dell, who joined the department after Sons died, said the jail still holds two or three people going through the commitment process each month.

John S. Farese, an attorney for Benton County, told Mississippi Today and ProPublica that the county, like others, “does the best they can do with the resources they have to abide by the laws” regarding commitments. He said the sheriff and the county will try to adapt to any changes in the law “while still being mindful of our limited personnel and financial resources.” He declined to comment on the specifics of the Sons case, which he didn’t work on.

Murray, Sons’ mother, was at a grocery store around noon the day her son died. As she picked out a watermelon, she thought about him, a fitness buff who loved fruits and vegetables. A strange thought crossed her mind: “Jimmy’s never going to eat watermelon again.”

When she got home, she got the call that he was gone.

John Sons, Jimmy’s half-brother, wrote in a text to Mississippi Today and ProPublica that the family is left with “complete and total guilt for putting him in the prison and always the wonder if we would not have done that move, if he would be with us today.”

But Richmond, the trusty who briefly shared a cell with Sons, testified that it was jail staff who “messed up.”

“He hung himself,” Richmond said. “I say this. God forgive me if I’m wrong. We couldn’t have saved that man from killing himself, but we could have saved that man from hanging himself in that jail.”

How we reported this story

No one in Mississippi has ever comprehensively tracked the number of people jailed at any point during the civil commitment process, according to interviews with dozens of state and county officials.

Last year, the state Department of Mental Health released, for the first time, a tally of people who were admitted to a state hospital directly from jail following civil commitment proceedings. The department tracked 734 placements in fiscal year 2022. (Under a law that takes effect this year, every county must regularly report to the department data regarding how often people are held in jail both before and after their commitment hearings.)

But that figure understates the scope of commitments. It doesn’t include people who were sent places other than a state hospital for treatment or who were released without being treated, and it counts only the time people spent in jail after their hearings. People can be jailed for 12 days before a commitment hearing, or longer if a county doesn’t follow the law.

County jail dockets can provide a more comprehensive picture, so Mississippi Today and ProPublica requested them from 80 of Mississippi’s 82 counties. Seventeen counties provided dockets that clearly marked bookings related to civil commitments — with notes including “writ to take custody,” “mental writ” and “lunacy.” In two more counties, we reviewed dockets in person.

Many counties didn’t respond, said their records were available only on paper or declined to provide records. Some cited a 2007 opinion by the state attorney general that sheriffs may choose not to enter the names of people detained during civil commitment proceedings onto their jail dockets.

After cleaning and standardizing the data from the dockets, we counted the number of jail stays involving civil commitments in which the person was not booked for a criminal charge on the same day. (We ended up excluding about 750 civil commitments for that reason.) If the dockets provided booking and release dates, we calculated the duration of jail stays.

Our count of commitments includes those for both mental illness and substance abuse. None of the jail dockets specified which commitment process people were going through, although some county officials said they don’t jail people committed for substance abuse and haven’t for years.

State laws regarding commitment for mental illness and substance abuse are different, but in many counties they were handled similarly until late 2021. That’s when the Mississippi attorney general’s office said state law didn’t allow people going through the drug and alcohol commitment process to be jailed.

To identify deaths of individuals held in jail during the civil commitment process, we reviewed news articles and federal court records. We also reviewed nearly 90 investigations of jail deaths from the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation. Most of the deaths had not previously been publicly reported.

For our survey of practices in other states, we contacted agencies overseeing mental health and disability advocacy organizations in every state and Washington, D.C. We received responses from one or the other in every location, and we received responses from both in 33. We also searched for news reports of similar cases in other states.

Do you have a story to share about someone who went through the civil commitment process in Mississippi? Contact Isabelle Taft at itaft@mississippitoday.org or call her at 601-691-4756.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Mississippi Legislature approves DEI ban after heated debate

Mississippi lawmakers have reached an agreement to ban diversity, equity and inclusion programs and a list of “divisive concepts” from public schools across the state education system, following the lead of numerous other Republican-controlled states and President Donald Trump’s administration.

House and Senate lawmakers approved a compromise bill in votes on Tuesday and Wednesday. It will likely head to Republican Gov. Tate Reeves for his signature after it clears a procedural motion.

The agreement between the Republican-dominated chambers followed hours of heated debate in which Democrats, almost all of whom are Black, excoriated the legislation as a setback in the long struggle to make Mississippi a fairer place for minorities. They also said the bill could bog universities down with costly legal fights and erode academic freedom.

Democratic Rep. Bryant Clark, who seldom addresses the entire House chamber from the podium during debates, rose to speak out against the bill on Tuesday. He is the son of the late Robert Clark, the first Black Mississippian elected to the state Legislature since the 1800s and the first Black Mississippian to serve as speaker pro tempore and preside over the House chamber since Reconstruction.

“We are better than this, and all of you know that we don’t need this with Mississippi history,” Clark said. “We should be the ones that say, ‘listen, we may be from Mississippi, we may have a dark past, but you know what, we’re going to be the first to stand up this time and say there is nothing wrong with DEI.'”

Legislative Republicans argued that the measure — which will apply to all public schools from the K-12 level through universities — will elevate merit in education and remove a list of so-called “divisive concepts” from academic settings. More broadly, conservative critics of DEI say the programs divide people into categories of victims and oppressors and infuse left-wing ideology into campus life.

“We are a diverse state. Nowhere in here are we trying to wipe that out,” said Republican Sen. Tyler McCaughn, one of the bill’s authors. “We’re just trying to change the focus back to that of excellence.”

The House and Senate initially passed proposals that differed in who they would impact, what activities they would regulate and how they aim to reshape the inner workings of the state’s education system. Some House leaders wanted the bill to be “semi-vague” in its language and wanted to create a process for withholding state funds based on complaints that almost anyone could lodge. The Senate wanted to pair a DEI ban with a task force to study inefficiencies in the higher education system, a provision the upper chamber later agreed to scrap.

The concepts that will be rooted out from curricula include the idea that gender identity can be a “subjective sense of self, disconnected from biological reality.” The move reflects another effort to align with the Trump administration, which has declared via executive order that there are only two sexes.

The House and Senate disagreed on how to enforce the measure but ultimately settled on an agreement that would empower students, parents of minor students, faculty members and contractors to sue schools for violating the law.

People could only sue after they go through an internal campus review process and a 25-day period when schools could fix the alleged violation. Republican Rep. Joey Hood, one of the House negotiators, said that was a compromise between the chambers. The House wanted to make it possible for almost anyone to file lawsuits over the DEI ban, while Senate negotiators initially bristled at the idea of fast-tracking internal campus disputes to the legal system.

The House ultimately held firm in its position to create a private cause of action, or the right to sue, but it agreed to give schools the ability to conduct an investigative process and potentially resolve the alleged violation before letting people sue in chancery courts.

“You have to go through the administrative process,” said Republican Sen. Nicole Boyd, one of the bill’s lead authors. “Because the whole idea is that, if there is a violation, the school needs to cure the violation. That’s what the purpose is. It’s not to create litigation, it’s to cure violations.”

If people disagree with the findings from that process, they could also ask the attorney general’s office to sue on their behalf.

Under the new law, Mississippi could withhold state funds from schools that don’t comply. Schools would be required to compile reports on all complaints filed in response to the new law.

Trump promised in his 2024 campaign to eliminate DEI in the federal government. One of the first executive orders he signed did that. Some Mississippi lawmakers introduced bills in the 2024 session to restrict DEI, but the proposals never made it out of committee. With the national headwinds at their backs and several other laws in Republican-led states to use as models, Mississippi lawmakers made plans to introduce anti-DEI legislation.

The policy debate also unfolded amid the early stages of a potential Republican primary matchup in the 2027 governor’s race between State Auditor Shad White and Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann. White, who has been one of the state’s loudest advocates for banning DEI, had branded Hosemann in the months before the 2025 session “DEI Delbert,” claiming the Senate leader has stood in the way of DEI restrictions passing the Legislature.

During the first Senate floor debate over the chamber’s DEI legislation during this year’s legislative session, Hosemann seemed to be conscious of these political attacks. He walked over to staff members and asked how many people were watching the debate live on YouTube.

As the DEI debate cleared one of its final hurdles Wednesday afternoon, the House and Senate remained at loggerheads over the state budget amid Republican infighting. It appeared likely the Legislature would end its session Wednesday or Thursday without passing a $7 billion budget to fund state agencies, potentially threatening a government shutdown.

“It is my understanding that we don’t have a budget and will likely leave here without a budget. But this piece of legislation …which I don’t think remedies any of Mississippi’s issues, this has become one of the top priorities that we had to get done,” said Democratic Sen. Rod Hickman. “I just want to say, if we put that much work into everything else we did, Mississippi might be a much better place.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

House gives Senate 5 p.m. deadline to come to table, or legislative session ends with no state budget

The House on Wednesday attempted one final time to revive negotiations between it and the Senate over passing a state budget.

Otherwise, the two Republican-led chambers will likely end their session without funding government services for the next fiscal year and potentially jeopardize state agencies.

The House on Wednesday unanimously passed a measure to extend the legislative session and revive budget bills that had died on legislative deadlines last weekend.

House Speaker Jason White said he did not have any prior commitment that the Senate would agree to the proposal, but he wanted to extend one last offer to pass the budget. White, a Republican from West, said if he did not hear from the Senate by 5 p.m. on Wednesday, his chamber would end its regular session.

“The ball is in their court,” White said of the Senate. “Every indication has been that they would not agree to extend the deadlines for purposes of doing the budget. I don’t know why that is. We did it last year, and we’ve done it most years.”

But it did not appear likely Wednesday afternoon that the Senate would comply.

The Mississippi Legislature has not left Jackson without setting at least most of the state budget since 2009, when then Gov. Haley Barbour had to force them back to set one to avoid a government shutdown.

The House measure to extend the session is now before the Senate for consideration. To pass, it would require a two-thirds majority vote of senators. But that might prove impossible. Numerous senators on both sides of the aisle vowed to vote against extending the current session, and Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann who oversees the chamber said such an extension likely couldn’t pass.

Senate leadership seemed surprised at the news that the House passed the resolution to negotiate a budget, and several senators earlier on Wednesday made passing references to ending the session without passing a budget.

“We’ll look at it after it passes the full House,” Senate President Pro Tempore Dean Kirby said.

The House and Senate, each having a Republican supermajority, have fought over many issues since the legislative session began early January.

But the battle over a tax overhaul plan, including elimination of the state individual income tax, appeared to cause a major rift. Lawmakers did pass a tax overhaul, which the governor has signed into law, but Senate leaders cried foul over how it passed, with the House seizing on typos in the Senate’s proposal that accidentally resembled the House’s more aggressive elimination plan.

The Senate had urged caution in eliminating the income tax, and had economic growth triggers that would have likely phased in the elimination over many years. But the typos essentially negated the triggers, and the House and governor ran with it.

The two chambers have also recently fought over the budget. White said he communicated directly with Senate leaders that the House would stand firm on not passing a budget late in the session.

But Senate leaders said they had trouble getting the House to meet with them to haggle out the final budget.

On the normally scheduled “conference weekend” with a deadline to agree to a budget last Saturday, the House did not show, taking the weekend off. This angered Hosemann and the Senate. All the budget bills died, requiring a vote to extend the session, or the governor forcing them into a special session.

If the Legislature ends its regular session without adopting a budget, the only option to fund state agencies before their budgets expire on June 30 is for Gov. Tate Reeves to call lawmakers back into a special session later.

“There really isn’t any other option (than the governor calling a special session),” Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann previously said.

If Reeves calls a special session, he gets to set the Legislature’s agenda. A special session call gives an otherwise constitutionally weak Mississippi governor more power over the Legislature.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Amount of federal cuts to health agencies doubles

Cuts to public health and mental health funding in Mississippi have doubled – reaching approximately $238 million – since initial estimates last week, when cancellations to federal grants allocated for COVID-19 pandemic relief were first announced.

Slashed funding to the state’s health department will impact community health workers, planned improvements to the public health laboratory, the agency’s ability to provide COVID-19 vaccinations and preparedness efforts for emerging pathogens, like H5 bird flu.

The grant cancellations, which total $230 million, will not be catastrophic for the agency, State Health Officer Dr. Daniel Edney told members of the Mississippi House Democratic Caucus at the Capitol April 1.

But they will set back the agency, which is still working to recover after the COVID-19 pandemic decimated its workforce and exposed “serious deficiencies” in the agency’s data collection and management systems.

The cuts will have a more significant impact on the state’s economy and agency subgrantees, who carry out public health work on the ground with health department grants, he said.

“The agency is okay. But I’m very worried about all of our partners all over the state,” Edney told lawmakers.

The health department was forced to lay off 17 contract workers as a result of the grant cancellations, though Edney said he aims to rehire them under new contracts.

Other positions funded by health department grants are in jeopardy. Two community health workers at Back Bay Mission, a nonprofit that supports people living in poverty in Biloxi, were laid off as a result of the cuts, according to WLOX. It’s unclear how many more community health workers, who educate and help people access health care, have been impacted statewide.

The department was in the process of purchasing a comprehensive data management system before the cuts and has lost the ability to invest in the Mississippi Public Health Laboratory, he said. The laboratory performs environmental and clinical testing services that aid in the prevention and control of disease.

The agency has worked to reduce its dependence on federal funds, Edney said, which will help it weather the storm. Sixty-six percent of the department’s budget is federally funded.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention pulled back $11.4 billion in funding to state health departments nationwide last week. The funding was originally allocated by Congress for testing and vaccination against the coronavirus as part of COVID-19 relief legislation, and to address health disparities in high-risk and underserved populations. An additional $1 billion from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration was also terminated.

“The COVID-19 pandemic is over, and HHS will no longer waste billions of taxpayer dollars responding to a non-existent pandemic that Americans moved on from years ago,” the Department of Health and Human Services Director of Communications Andrew Nixon said in a statement.

HHS did not respond to questions from Mississippi Today about the cuts in Mississippi.

Democratic attorneys general and governors in 23 states filed a lawsuit against the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Tuesday, arguing that the sudden cancellation of the funding was unlawful and seeking injunctive relief to halt the cuts. Mississippi did not join the suit.

Mental health cuts

The Department of Mental Health received about $7.5 million in cuts to federal grants from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Over half of the cuts were to community mental health centers, and supported alcohol and drug treatment services for people who can not afford treatment, housing services for parenting and pregnant women and their children, and prevention services.

The cuts could result in reduced beds at community mental health centers, Phaedre Cole, the director of Life Help and President of Mississippi Association of Community Mental Health Centers, told lawmakers April 1.

Community mental health centers in Mississippi are already struggling to keep their doors open. Four centers in the state have closed since 2012, and a third have an imminent to high risk of closure, Cole told legislators at a hearing last December.

“We are facing a financial crisis that threatens our ability to maintain our mission,” she said Dec. 5.

Cuts to the department will also impact diversion coordinators, who are charged with reducing recidivism of people with serious mental illness to the state’s mental health hospital, a program for first-episode psychosis, youth mental health court funding, school-aged mental health programs and suicide response programs.

The Department of Mental Health hopes to reallocate existing funding from alcohol tax revenue and federal block grant funding to discontinued programs.

The agency posted a list of all the services that have received funding cuts. The State Department of Health plans to post such a list, said spokesperson Greg Flynn.

Health leaders have expressed fear that there could be more funding cuts coming.

“My concern is that this is the beginning and not the end,” said Edney.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

-

Mississippi Today1 day ago

Mississippi Today1 day agoPharmacy benefit manager reform likely dead

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days agoSevere storms will impact Alabama this weekend. Damaging winds, hail, and a tornado threat are al…

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days agoUniversity of Alabama student detained by ICE moved to Louisiana

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed4 days agoTornado watch, severe thunderstorm warnings issued for Oklahoma

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed6 days agoA little early morning putting at the PGA Tour Superstore

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Virginia News Feed6 days agoYoungkin removes Ellis, appoints Cuccinelli to UVa board | Virginia

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days agoPeanut farmer wants Florida water agency to swap forest land

-

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed5 days agoHometown Hero | Restaurant owner serves up hope