Mississippi Today

Sex Abuse, Beatings and an Untouchable Mississippi Sheriff

Sex Abuse, Beatings and an Untouchable Mississippi Sheriff

Terry Grassaree was dogged for years by questions about how he did his job as a law enforcement officer in Macon, Miss., a tiny, rural town near the state’s eastern border.

There were allegations of rape inside the jail that Mr. Grassaree supervised, and lawsuits claiming that he covered up the episodes. At least five people, including one of his fellow deputies, accused him of beating others or choking them with a police baton.

Mr. Grassaree survived it all, rising in the ranks of the Noxubee County Sheriff’s Department, from a deputy mopping floors, to chief deputy, to the elected position of sheriff, making him one of the most powerful figures in town.

Now, more than three years after losing an election and retiring, and 16 years after a woman first claimed that Mr. Grassaree pressured her to lie about being raped, the former sheriff faces criminal charges.

A federal indictment filed in October accuses him of committing bribery in 2019, near the end of his eight-year tenure as sheriff, and of lying to federal agents when they questioned him about whether he requested sexually explicit photographs and videos from a female inmate. Mr. Grassaree has denied the charges and pleaded not guilty.

But an investigation by the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reportingat Mississippi Todayand The New York Times reveals that allegations of wrongdoing against Mr. Grassaree have been far more wide-ranging and serious than those federal charges suggest. The investigation included a review of nearly two decades of lawsuit depositions and a previously undisclosed report by the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation.

At a minimum, the documents detail gross mismanagement at the Noxubee County jail that repeatedly put female inmates in harm’s way. At worst, they tell the story of a sheriff who operated with impunity, even as he was accused of abusing the people in his custody, turning a blind eye to women who were raped and trying to cover it up when caught.

Over nearly two decades, as allegations mounted and Noxubee County’s insurance company paid to settle lawsuits against Mr. Grassaree, state prosecutors brought no charges against him or others accused of abuses in the jail. A federal investigation dragged on for years, and led to charges last fall, a few weeks after reporters started asking authorities about the case.

Even now, no higher authority has reviewed how Mr. Grassaree ran the jail or whether his policies endangered women, because in Mississippi, as in many states, rural sheriffs are left largely to police themselves and their jails.

In 2006, after Mr. Grassaree and his staff left jail cell keys hanging openly on a wall, male inmates opened the doors to the cell of two women inmates and raped them, according to statements the women gave to state investigators. One of the women said Mr. Grassaree pressured her to sign a false statement to cover up the crimes, according to the state police report that has never been made public.

About a year later, in a lawsuit, four people who had been arrested gave sworn statements accusing Mr. Grassaree of violence. Two of the people said he choked or beat them while they were in his custody. A third said he pinned her against a wall and threatened to let a male inmate rape her.

In 2019, a jailed woman told investigators that she had been coerced into having sex with two deputies who offered her a cellphone in exchange for her compliance. Instead of punishing the deputies, she claimed in a lawsuit against the county, Mr. Grassaree demanded that she send him explicit pictures and videos of herself. The federal indictment also accuses Mr. Grassaree of using his cellphone to facilitate a bribe, which experts say could have been the perks the woman says she received.

All told, at least eight men — including four deputies and Mr. Grassaree himself — have been accused of sex abuse by women inmates who were being held in the Noxubee County jail while Mr. Grassaree was in charge.

Over the years, the accusations of rape and other misconduct at the jail have been investigated separately by the FBI, the Department of Justice and the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation. No rape or assault charges have been filed.

Mr. Grassaree has denied all of the allegations against him and has faced no disciplinary action. His lawyer declined to comment further.

Holding people accountable for rapes and assaults behind bars is difficult under the best of circumstances. There is little to protect incarcerated victims and witnesses from retaliation for speaking up. When they do come forward, they are often dismissed as not credible, especially if the person accused is a law enforcement officer.

What happened inside the Noxubee jail, and how the authorities responded, is a case study in how those difficulties can be even harder to surmount in rural places, where jails are the exclusive domain of a county sheriff who operates largely without oversight.

No state agency oversees Mississippi’s county jails, and no state regulator has the authority to fine a sheriff for endangering people in custody or for failing to train the staff who operate the jail. In 2017, state lawmakers stopped providing funds for jail inspections by the Mississippi Department of Health, removing even the basic requirement that the facilities meet food safety and cleanliness requirements.

“They are closed-off institutions, and the people held inside them are unpopular and politically powerless,” said David Fathi, director of the American Civil Liberties Union National Prison Project. “That makes them ripe for neglect and abuse that is entirely foreseeable.”

Scott Colom, the elected district attorney for Noxubee County, took office in 2016 and was not involved in the investigation of the 2006 rape allegations.

After learning of the more recent allegations against Mr. Grassaree and his deputies, Mr. Colom said, he notified federal authorities and worked with them on an investigation. Although he believed the evidence against Mr. Grassaree in the case was “clear and strong,” Mr. Colom said he knew it would be tough to seat an impartial jury in Noxubee County. He has twice been forced to cancel criminal trials because there were too few potential jurors available, he said, and neither of those cases involved a public official.

Darren J. LaMarca, U.S. attorney for the Southern District of Mississippi, declined to comment on the case and so did others responsible for investigating the alleged abuses in the Noxubee County jail.

Mr. Grassaree spoke briefly in an interview about his professional history, but would not answer detailed questions about the 2006 rape cases or the more recent allegations related to his federal charges.

Mary Taylor, a retired dispatcher who worked full time at the jail from 1988 to 2017, said in a phone interview that in her years at the jail she never witnessed any sexual abuse.

She said she wasn’t working on the day the two women said the rapes took place in 2006, but that she doesn’t believe their version of events.

“My belief? They weren’t raped,” Ms. Taylor said. “They did that to get out of jail.”

She maintained that it’s “impossible for one man to rape a woman, unless she’s not moving, unless it’s a Bill Cosby thing.”

“They could have yelled out and told somebody,” she said. “You can’t rape the unwilling.”

Building a tough reputation

When Terry Grassaree was born in Macon in 1962, the idea that he could one day be sheriff seemed far-fetched.

In Macon, which briefly served as Mississippi’s capital during the Civil War, only white men worked as law enforcement officers in those days. The county had a long history of violence against African Americans, including the massacre of 13 Black Mississippians at a church, gunned down by nightriders on a single August night in 1871. The sheriff at the time arrested no one.

Though the county’s population is mostly Black, every sheriff elected in Noxubee County was white until 1988, when Albert Walker became the first Black man to hold the office. Mr. Grassaree, his handpicked successor, was the second.

Mr. Grassaree started his law enforcement career as a police officer in Macon and in nearby Brooksville, and sold insurance on the side to help make ends meet. Sheriff Walker hired him as a county deputy in 1992 and put him to work mopping floors, among other duties, at the county jail. Mr. Grassaree was also a deputy coroner, paid $85 for each body he handled.

He worked his way up to chief deputy, and took on running the jail.

Mr. Grassaree, known to keep order by issuing physical threats, said in an interview last year that he drew inspiration from the professional wrestler “Stone Cold” Steve Austin.

“Even while they were whipping him, he was still the toughest guy on the mat,” Mr. Grassaree said. “He’s like, ‘Is that all you’ve got?’ No matter how long a man whips you, he will get tired. He might think he’s winning. The only thing you’ve got to do is hold out.”

This idea, he said, became the foundation for how he behaved when he put on his uniform.

Early in his career, he beefed his 6-foot-2 frame up to 230 pounds, and people started calling him “Big Dog.” Not many people crossed him after that, he said.

His reputation for being aggressive spread across town. In a 2006 letter to the editor in the local paper, a mother complained that Mr. Grassaree had threatened her 16-year-old son. The boy, she wrote, had fought with Mr. Grassaree’s son at school.

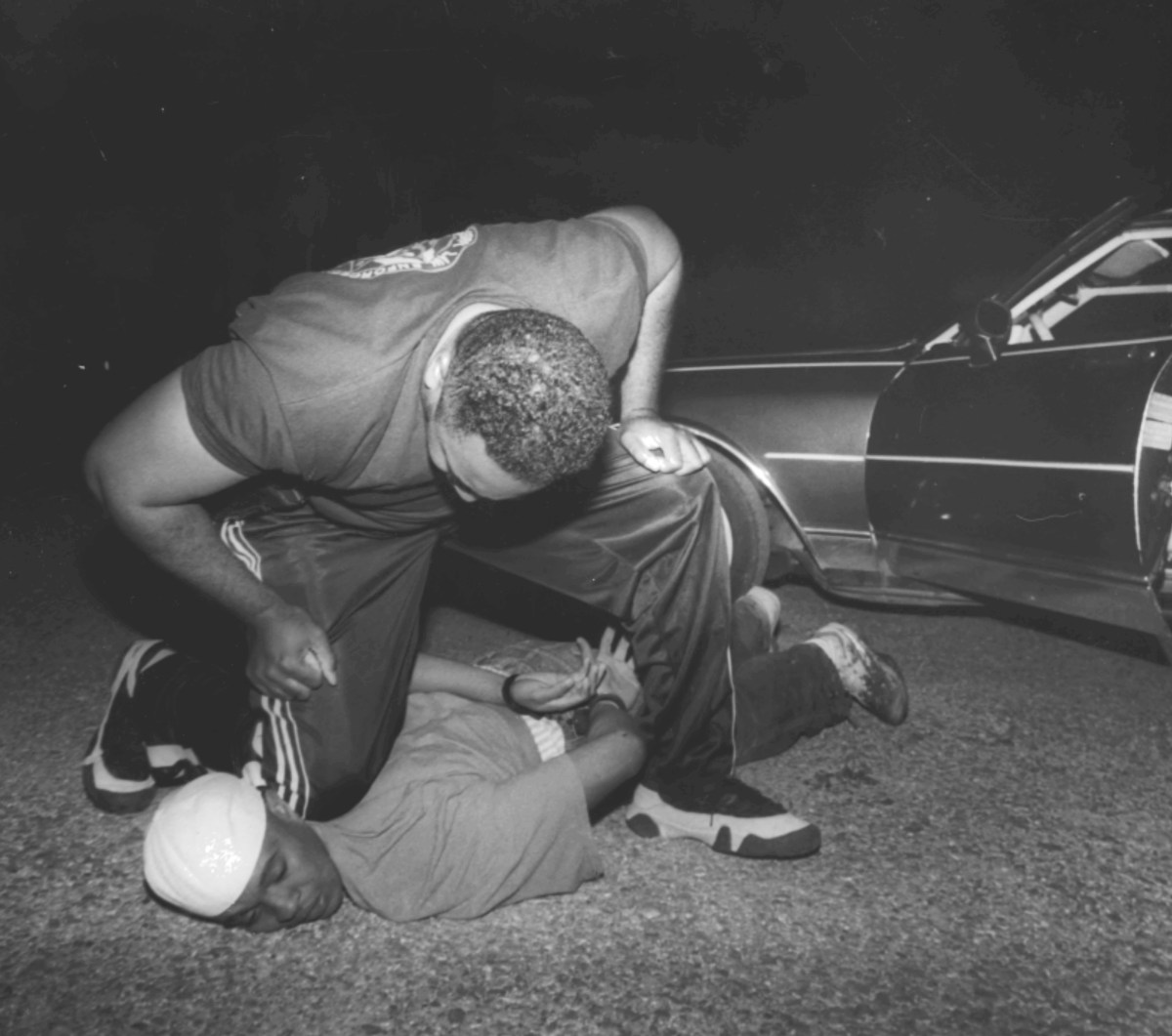

The editor of the same newspaper, The Macon Beacon, arrived to cover an arrest near a nightclub in 2000 and snapped a picture of Mr. Grassaree kneeling on a man’s neck. The photo made the front page.

People who passed through the jail describe being attacked by Mr. Grassaree when he thought they were causing trouble. Four people gave sworn statements about such attacks as part of a 2005 lawsuit against Mr. Grassaree and Noxubee County filed by former deputy Kendrick Slaughter. In the lawsuit, Mr. Slaughter claimed that Mr. Grassaree tried to bribe him not to run for City Council, and then hauled him to jail for talking to the FBI about the alleged bribe.

Noxubee County’s insurance company settled the suit for an undisclosed amount.

The four sworn statements accuse Mr. Grassaree of a number of violent acts, which he has denied committing. One man wrote that while he was handcuffed in a courtroom in 2002, Mr. Grassaree beat him until a judge came off the bench to rescue him.

Another man said in his sworn statement that Mr. Grassaree choked him with his nightstick and warned him to follow his orders. The man said Mr. Grassaree told him, “I’ll shoot you in the head! I’m the Big Dog! I’m Number One! This my jail!”

A 19-year-old woman said Mr. Grassaree hit her twice with his nightstick and threw her against a wall after accusing her of stealing potato chips from a man held in jail. Mr. Grassaree “spread my legs apart with his foot,” she said in her deposition.

Then, she said, he told her that he ought to let the inmate rape her.

A jail with no rules

The jail that Mr. Grassaree oversaw for most of his career sits frozen in time on Industrial Road on the outskirts of Macon, next to the old Purina pet food mill that now produces feed for catfish farms.

The building has been locked and empty since about 2014, when Mr. Grassaree and his deputies packed up and moved to a new facility down the street. Inside the old jail, a blackened mix of dirt, rust and mold has crept over the white iron cell doors. Bags of trash and dusty bed linens litter the remaining furniture and the floor.

When Mr. Grassaree was put in charge of this building in the 1990s, he inherited a jailhouse that essentially operated without rules. Jail workers allowed inmates to come and go from the building without logging the inmates’ movements or supervising them closely.

The onlypolicies about the jail that appear in the 2003 Noxubee County Sheriff’s Policy Manual center on the use of force. None tell how to run the jail.

For years, certain inmates were let out of their cells to help cook, pass out food trays and clean.

Kennedy Brewer, who entered the jail in 2002, was one of the facility’s most trusted inmates. Eyebrows were raised when he showed up at a court hearing on his own, having driven himself to the courthouse without a deputy to escort him, according to Forrest Allgood, the district attorney at the time.

Mr. Brewer spent five years at the jail waiting to be retried after DNA evidence proved he had been wrongly convicted of sexually abusing and murdering a 3-year-old girl. When prosecutors gave up on a new trial, Mr. Brewer was released, and his case was featured in the Netflix documentary series “The Innocence Files.”

Testifying under oath as a witness in a lawsuit in 2007, Mr. Brewer said he served as a jail trusty, or an inmate with special privileges, and had access to keys that opened each cell. He said he would check newly arrested people into the jail and that he once escorted an inmate to a cell with no one else present.

Mr. Grassaree has denied that inmates were allowed to use jail keys without supervision.

On a June day in 2006, Mr. Brewer had no problem getting into the women’s cell block undetected.

He grabbed the jailer’s keys off the nail hanging on the wall and slipped down the short hallway that ran the length of jail. In a building smaller than a McDonald’s, he and a fellow inmate didn’t have to go far. There were no guards patrolling the halls and no surveillance cameras to catch any movements.

When Mr. Brewer unlocked the cell door, one of the women inside was laying down for a nap.

Then Brewer was on top of her, grabbing her arms and forcing her down, according to statements the first woman later gave to state agents.

“No, I don’t want to do this,” she begged, according to her statements.

Then she looked for her cellmate, Jessie Levette Douglas. She told investigators she saw another inmate, Laterris Goodwin, on top of her.

It was all over in moments.

The woman who originally reported the rapes declined to be interviewed for this article. Ms. Douglas died of renal failure in a state prison in 2018.

When investigators interview rape victims, they are supposed to remain impartial. But when Mr. Grassaree, who was chief deputy at the time, found the woman crying on the floor, he stood over her and shouted, the woman said in a deposition taken as part of her subsequent lawsuit against the county. He and another member of the sheriff’s office yelled that she couldn’t tell anybody about the rape and that she was “going to make them lose their jobs and make the department look bad,” according to her sworn statement.

“They kept berating me as if I had done something wrong,” she said.

When state agents arrived the next day at the request of the sheriff’s office, Mr. Grassaree handed them everything they needed to dismiss the allegations, including signed statements from two of the men saying the women had invited them to have sex, and more important, a statement from Ms. Douglas saying everything she saw and experienced was consensual.

If Mr. Grassaree and his deputies had been in charge of the investigation, it might have ended there. But when state agents interviewed Ms. Douglas, her story changed.

She told investigators that she and her cellmate had been raped that day and that she lied in her first statement because Mr. Grassaree had pressured her to cover up what happened.

Mr. Grassaree “told me to tell everybody the sex was consensual and that for me to ‘help a brother,’ referring to Brewer,”Ms. Douglaswrote in a later statement. “He told me to tell everybody that we put on a freak show for the male inmates.”

In reality, Ms. Douglas told the agents, three men incarcerated at the jail — Mr. Brewer, Mr. Goodwin and Michael Slaughter — had entered her locked cell at different times on the same day and had raped her.

In statements to investigators, Mr. Slaughter, Mr. Brewer and Mr. Goodwin denied that they had raped the women, claiming that the sex was consensual.

In an interview from 2022, Mr. Brewerdenied ever having sex with anyone inside the jail. Neither Mr. Slaughter nor Mr. Goodwin could be reached for comment.

Both women were given polygraph tests, and the examiner concluded that they were telling the truth, according to state investigators’ records. Mr. Goodwin and Mr. Slaughter failed polygraph tests; Mr. Brewer declined to take one.

State agents shared their findings with federal and state prosecutors, and the case was presented to a Noxubee County grand jury. The grand jury decided not to issue charges.

Legal experts say Mr. Grassaree could have been investigated for obstructing justice in the case. That never happened, and neither did an investigation of practices in the jail, where agents concluded that four rapes had taken place.

Noxubee County’s insurance company settled the woman’s lawsuit in 2009. The Macon Beacon reported that she was paid $375,000.

Sabrina Campbell said her sister, Ms. Douglas — the woman who said she was raped by three inmates and who died many years later — wanted the public to know what happened to her. “I don’t want my sister to have died in vain,” Ms. Campbell said.

The rapes devastated her sister, who never stopped battling nightmares afterward, she said. “She was scared all the time. She would tell nieces and nephews about the jail, ‘Don’t ever come here, because your life is over.’”

Another round of allegations

Allegations of sexual abuse at the Noxubee County jail did not end with the 2006 case.

In 2020, Elizabeth Layne Reed,a woman incarcerated at the jail, made explosive allegations against the men she encountered there. In a lawsuit she filed that year, she accused two deputies, Vance Phillips and Damon Clark, of coercing her into having sex.

She said the men gave her a cellphone and other perks so that she would have sexual encounters with them in remote spots around the jail or when the deputies checked her out of the facility. The deputies even put a sofa in her jail cell, she said.

Ms. Reed said in an interview that she wanted the public to know what happened to her in the hope that others would come forward. “It made me terrified to trust anybody,” she said. “Women in jail and prison need to be protected.”

According to her lawsuit, Mr. Grassaree knew all about his deputies’ “sexual contacts and shenanigans,” but did nothing to “stop the coerced sexual relationships.” Mr. Grassaree denied any knowledge of what deputies were doing. “Are you a boss?” he said. “Do your employees tell you everything they do?”

Instead of intervening, the lawsuit alleged, the sheriff “sexted” her and demanded that she use the phone the deputies had given her to send him “a continuous stream of explicit videos, photographs and texts” while she was in jail. She also alleged in the lawsuit that Mr. Grassaree touched her in a “sexual manner.”

The lawsuit was settled for an undisclosed amount.

News outlets in Mississippi made brief mention of the lawsuit, but government officials at all levels, including federal and state prosecutors, were silent for two years about what, if anything, they were doing to investigate the allegations it raised, and whether they had found evidence to support them.

A review by the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting and The New York Times of documents filed in the lawsuit, along with documents fromthe preceding2019 state investigation, reveals that Ms. Reedaccused other deputies besides Mr. Phillips and Mr. Clark of sexual harassment and abuse. None of the other deputies has been charged or named publicly. It is unclear whether the FBI investigated those allegations.

The federal bureau’s investigation into Mr. Grassaree, Mr. Phillips and Mr. Clark took more than two years to yield charges, even though investigators had confessions of sexual contact from the deputies as well as text messages between the woman and the three men. In fall of 2022, several weeks after reporters began asking authorities about the case, Mr. LaMarca successfully sought indictments against Mr. Grassaree and Mr. Phillips on bribery charges. Mr. Clark has not been indicted.

Ms. Reed hoped that other deputies, including Mr. Clark, would be held accountable, she said. “They’re still walking around free, not worried about any charges.”

Ms. Reed said that she felt sick to her stomach when she found out that neither Mr. Grassaree nor Mr. Phillips had been directly charged in connection with her allegations of sex abuse. Lawyers for Mr. Phillips did not immediately respond to requests for comment. Mr. Clark could not be reached for comment.

The indictments do not mention sexual abuse. Along with bribery, Mr. Grassaree was also charged with lying to the F.B.I. in denying that he had “requested and received” nude photos and videos from Ms. Reed. A trial is scheduled for summer.

Julie Abbate, who served as the deputy chief of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division from 2003 to 2018 and reviewed the allegations at the news organizations’ request, said the federal prosecutors could have explored criminal charges against Mr. Grassaree and his deputies for violating the civil rights of women in his facility.

The question of whether to bring federal charges in the case may have been complicated by guidance the Department of Justice issued in 2018, saying that law enforcement officers cannot be federally prosecuted for violating a person’s civil rights if the person “truly made a voluntary decision as to what she wanted to do with her body,” particularly if she received a benefit or special treatment in exchange for sex.

But Ms. Reed’s decisions in the episode in the Noxubee County jail were “not free-will choices,” said Andrea Armstrong, a law professor at Loyola University, and the cellphone Ms. Reed received from deputies “was the vehicle by which more abuse could be directed towards her.”

Mississippi law makes it a crime for law enforcement officers to engage in sexual acts with incarcerated people. Prosecutors are not required to prove the victims were physically overpowered or even that they told their abuser to stop.

But the district attorney’s office that handles criminal cases in Noxubee County chose to pass the 2020case on to federal prosecutors, instead of seeking charges under the state law, because of worries about getting a fair jury in the county. When asked about federal prosecutors’ decision to charge Mr. Grassaree and Mr. Phillips with bribery in the case, the district attorney, Mr. Colom, said, “I trust federal authorities to use the best statutes.”

Ms. Abbate said the allegations about abuses in the Noxubee County jail were indicative of a larger, pervasive problem at the facility and a harmful culture inside the sheriff’s office. That culture, she said, undoubtedly endangered inmates and allowed abuses to continue.

“The allegations that come to light are almost always just the tip of the iceberg,” said Ms. Abbate, who is now director of Just Detention International, an organization dedicated to ending sexual abuse in correctional facilities. Referring to the 2006 and 2020 cases, she said, “I guarantee you that these two instances are not the only ones.”

This article was co-reported by The New York Times and the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting at Mississippi Today.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Hospitals see danger in Medicaid spending cuts

Mississippi hospitals could lose up to $1 billion over the next decade under the sweeping, multitrillion-dollar tax and policy bill President Donald Trump signed into law last week, according to leaders at the Mississippi Hospital Association.

The leaders say the cuts could force some already-struggling rural hospitals to reduce services or close their doors.

The law includes the largest reduction in federal health and social safety net programs in history. It passed 218-214, with all Democrats voting against the measure and all but five Republicans voting for it.

In the short term, these cuts will make health care less accessible to poor Mississippians by making the eligibility requirements for Medicaid insurance stiffer, likely increasing people’s medical debt.

In the long run, the cuts could lead to worsening chronic health conditions such as diabetes and obesity for which Mississippi already leads the nation, and making private insurance more expensive for many people, experts say.

“We’ve got about a billion dollars that are potentially hanging in the balance over the next 10 years,” Mississippi Hospital Association President Richard Roberson said Wednesday during a panel discussion at his organization’s headquarters.

“If folks were being honest, the entire system depends on those rural hospitals,” he said.

Mississippi’s uninsured population could increase by 160,000 people as a combined result of the new law and the expiration of Biden-era enhanced subsidies that made marketplace insurance affordable – and which Trump is not expected to renew – according to KFF, a health policy research group.

That could make things even worse for those who are left on the marketplace plans.

“Younger, healthier people are going to leave the risk pool, and that’s going to mean it’s more expensive to insure the patients that remain,” said Lucy Dagneau, senior director of state and local campaigns at the American Cancer Society.

Among the biggest changes facing Medicaid-eligible patients are stiffer eligibility requirements, including proof of work. The new law requires able-bodied adults ages 19 to 64 to work, do community service or attend an educational program at least 80 hours a month to qualify for, or keep, Medicaid coverage and federal food aid.

Opponents say qualified recipients could be stripped of benefits if they lose a job or fail to complete paperwork attesting to their time commitment.

Georgia became the case study for work requirements with a program called Pathways to Coverage, which was touted as a conservative alternative to Medicaid expansion.

Ironically, the 54-year-old mechanic chosen by Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp to be the face of the program got so fed up with the work requirements he went from praising the program on television to saying “I’m done with it” after his benefits were allegedly cancelled twice due to red tape.

Roberson sent several letters to Mississippi’s congressional members in weeks leading up to the final vote on the sweeping federal legislation, sounding the alarm on what it would mean for hospitals and patients.

Among Roberson’s chief concerns is a change in the mechanism called state directed payments, which allows states to beef up Medicaid reimbursement rates – typically the lowest among insurance payors. The new law will reduce those enhanced rates to nearly as low as the Medicare rate, costing the state at least $500 million and putting rural hospitals in a bind, Roberson told Mississippi Today.

That change will happen over 10 years starting in 2028. That, in conjunction with the new law’s one-time payment program called the Rural Health Care Fund, means if the next few years look normal, it doesn’t mean Mississippi is safe, stakeholders warn.

“We’re going to have a sort of deceiving situation in Mississippi where we look a little flush with cash with the rural fund and the state directed payments in 2027 and 2028, and then all of a sudden our state directed payments start going down and that fund ends and then we’re going to start dipping,” said Leah Rupp Smith, vice president for policy and advocacy at the Mississippi Hospital Association.

Even with that buffer time, immediate changes are on the horizon for health care in Mississippi because of fear and uncertainty around ever-changing rules.

“Hospitals can’t budget when we have these one-off programs that start and stop and the rules change – and there’s a cost to administering a program like this,” Smith said.

Since hospitals are major employers – and they also provide a sense of safety for incoming businesses – their closure, especially in rural areas, affects not just patients but local economies and communities.

U.S. Rep. Bennie Thompson is the only Democrat in Mississippi’s congressional delegation. He voted against the bill, while the state’s two Republican senators and three Republican House members voted for it. Thompson said in a statement that the new law does not bode well for the Delta, one of the poorest regions in the U.S.

“For my district, this means closed hospitals, nursing homes, families struggling to afford groceries, and educational opportunities deferred,” Thompson said. “Republicans’ priorities are very simple: tax cuts for (the) wealthy and nothing for the people who make this country work.”

While still colloquially referred to as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, the name was changed by Democrats invoking a maneuver that has been used by lawmakers in both chambers to oppose a bill on principle.

“Democrats are forcing Republicans to delete their farcical bill name,” Senate Democratic Leader Charles Schumer of New York said in a statement. “Nothing about this bill is beautiful — it’s a betrayal to American families and it’s undeserving of such a stupid name.”

The law is expected to add at least $3.3 trillion to the nation’s debt over the next 10 years, according to the most recent estimate from the Congressional Budget Office.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Hospitals see danger in Medicaid spending cuts appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article reports on the negative impacts of a major federal tax and policy bill on Medicaid funding and rural hospitals in Mississippi. While it presents factual details and statements from stakeholders, the tone and framing emphasize the harmful consequences for vulnerable populations and health care access, aligning with concerns typically raised by center-left perspectives. The article highlights opposition by Democrats and critiques the bill’s priorities, particularly its effect on poor and rural communities, suggesting sympathy toward social safety net preservation. However, it maintains mostly factual reporting without overt partisan language, resulting in a moderate center-left bias.

Crooked Letter Sports Podcast

Podcast: The Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame Class of ’25

The MSHOF will induct eight new members on Aug 2. Rick Cleveland has covered them all and he and son Tyler talk about what makes them all special.

Stream all episodes here.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Podcast: The Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame Class of '25 appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Mississippi Today

‘You’re not going to be able to do that anymore’: Jackson police chief visits food kitchen to discuss new public sleeping, panhandling laws

Diners turned watchful eyes to the stage as Jackson Police Chief Joseph Wade took to the podium. He visited Stewpot Community Services during its daily free lunch hour Thursday to discuss new state laws, which took effect two days earlier, targeting Mississippians experiencing homelessness.

“I understand that you are going through some hard times right now. That’s why I’m here,” Wade said to the crowd. “I felt it was important to come out here and speak with you directly.”

Wade laid out the three bills that passed earlier this year: House Bill 1197, the “Safe Solicitation Act,” HB 1200, the “Real Property Owners Protection Act” and HB 1203, a bill that prohibits camping on public property.

“Sleeping and laying in public places, you’re not going to be able to do that anymore,” he said. “There’s a law that has been passed that you can’t just set up encampments on public or private properties where it’s a public nuisance, it’s a problem.”

The “Real Property Owners Protection Act,” authored by Rep. Brent Powell, R-Brandon, is a bill that expedites the process of removing squatters. The “Safe Solicitation Act,” authored by Rep. Shanda Yates, I-Jackson, requires a permit for panhandling and allows people to be charged with a misdemeanor if they violate this law. The offense is punishable by a fine not to exceed $300 and an offender could face up to six months in jail. Wade said he’s currently working with his legal department to determine the best strategy for creating and issuing permits.

“We’re going to navigate these legal challenges, get some interpretations, not only from our legal department, but the Attorney General’s office to ensure that we are doing it legally and lawfully, because I understand that these are citizens,” he said. “I understand that they deserve to be treated with respect, and I understand that we are going to do this without violating their constitutional rights.”

Wade said the Jackson Police Department is steadily fielding reports of squatters in abandoned properties and the law change gives officers new power to remove them more quickly. The added challenge? Figuring out what to do with a person’s belongings.

“These people are carrying around what they own, but we are not a repository for all of their stuff,” he said. “So, when we make that arrest, we’ve got to have a strategic plan as to what we do with their stuff.”

Wade said there needs to be a deeper conversation around the issues that lead someone to becoming homeless.

“A lot of people that we’re running across that are homeless are also suffering from medical conditions, mental health issues, and they’re also suffering from drug addiction and substance abuse. We’ve got to have a strategic approach, but we also can’t log jam our jail down in Raymond,” Wade said.

He estimates that more than 800 people are currently incarcerated at the Raymond Detention Center, and any increase could strain the system as the laws continue to be enforced.

“I think there’s layers that we have to work through, there’s hurdles that we are going to overcome, but we’ve got to make sure that we do it and make sure that my team and JPD is consistent in how we enforce these laws,” Wade said.

Diners applauded Wade after he spoke, in between bites of fried chicken, salad, corn and 4th of July-themed packaged cakes. Wade offered to answer questions, but no one asked any.

Rev. Jill Buckley, executive director of Stewpot, said that the legislation is a good tool to address issues around homelessness and community needs. She doesn’t want to see people who are homeless be criminalized, but she also wants communities to be safe.

“I support people’s right to self determine, and we can’t impose our choices on other people, but there are some cases in which that impinges on community safety, and so to the extent that anyone who is camping or panhandling or squatting and is a danger to themselves and others, of course, I fully support that kind of law. I don’t support homelessness being criminalized as such,” Buckley said.

Many of the people Wade addressed while they ate Thursday said they have housing, don’t panhandle, and shouldn’t be directly impacted by the legislation. But Marcus Willis, 42, said it would make more sense if elected officials wanted to combat the negative impacts of homelessness that they help more people secure employment.

“There ain’t enough jobs,” said Willis, who was having lunch with his girlfriend Amber Ivy.

The two live in an apartment together nearby on Capitol Street, where Ivy landed after her mother, whom Ivy had been living with, suffered a stroke and lost the property. Similarly, Willis started coming to eat at Stewpot after his grandmother, whose house he used to visit for lunch, passed away.

Willis holds odd jobs – cutting grass, home and auto repair – so the income is inconsistent, and every opportunity for stable employment he said he’s found is outside of Jackson in the suburbs. The couple doesn’t have a car.

Making rent every month usually depends on their ability to find someone to help chip in, said Ivy, who is in recovery from substance abuse. She said she’s watched problems surrounding homelessness grow over the years in Jackson. Ivy grew up near Stewpot and has lived in various neighborhoods across the city – except for the times she moved out of state when things got too rough.

“There was just moments where I just had to leave,” Ivy said. “Sometimes if you hit a slump here, there’s almost no way for you to get out of it.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post 'You're not going to be able to do that anymore': Jackson police chief visits food kitchen to discuss new public sleeping, panhandling laws appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Right

This article primarily reports on new laws in Jackson, Mississippi, targeting public sleeping, panhandling, and squatting, focusing on statements by Police Chief Joseph Wade and community perspectives. The coverage presents the legislative measures—authored by Republican and independent lawmakers—with a tone that emphasizes law enforcement challenges and community safety, reflecting a conservative approach to homelessness as a public order issue. While it includes voices concerned about criminalization and the need for social support, the overall framing centers on law enforcement and property protection. The article maintains factual reporting without overt editorializing but leans slightly toward a center-right perspective by highlighting legal enforcement as a solution.

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days ago

Real-life Uncle Sam's descendants live in Arkansas

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed5 days ago

'Big Beautiful Bill' already felt at Georgia state parks | FOX 5 News

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed6 days ago

LOFT report uncovers what led to multi-million dollar budget shortfall

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago

Alabama schools to lose $68 million in federal grants under Trump freeze

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days ago

Celebrate St. Louis returns with new Superman-themed drone show

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed6 days ago

Tropical Depression Three to bring rain, gusty winds to the CSRA this Fourth of July weekend

-

The Center Square4 days ago

Here are the violent criminals Judge Murphy tried to block from deportation | Massachusetts

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed7 days ago

What’s being explored at the ‘Pit of Despair?’ Razor wire OK atop fence within city limits? Mystery pile of dirt along I-26? • Asheville Watchdog