Mississippi Today

A look inside one Mississippi mom’s life a year after giving birth

A look inside one Mississippi mom’s life a year after giving birth

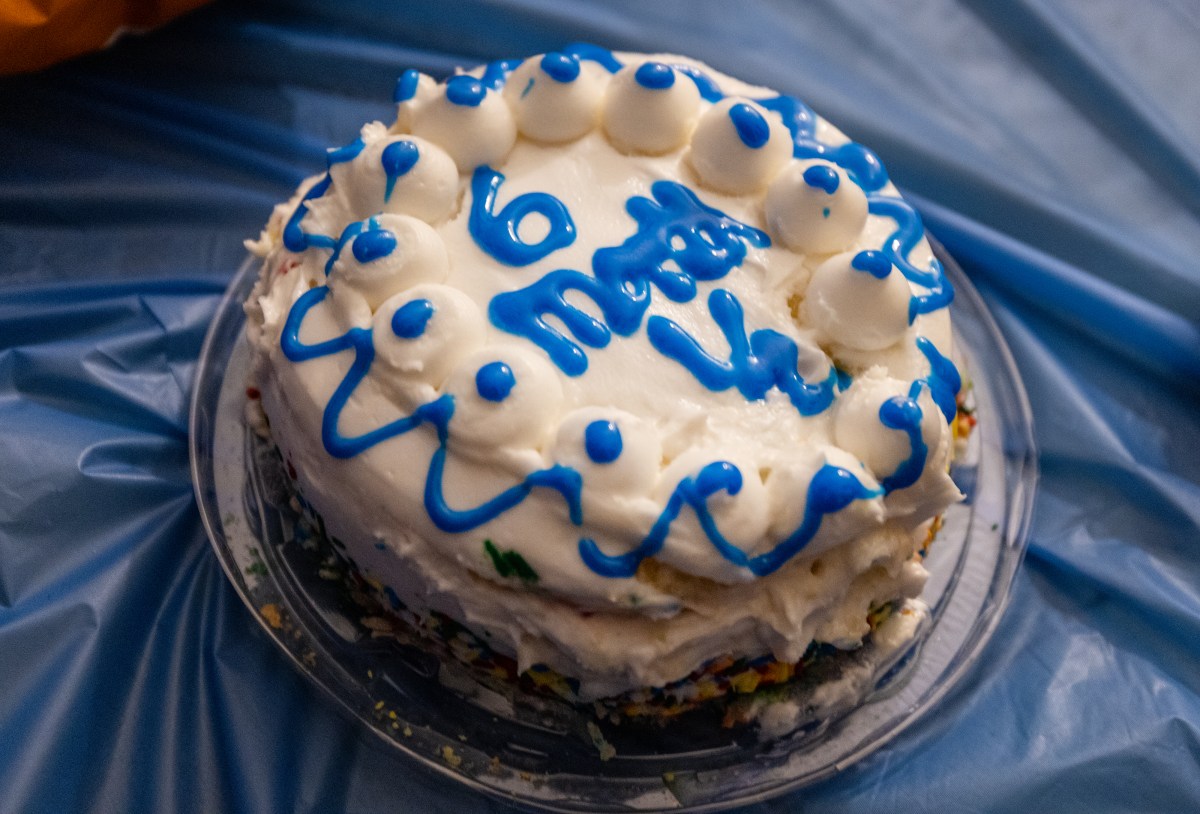

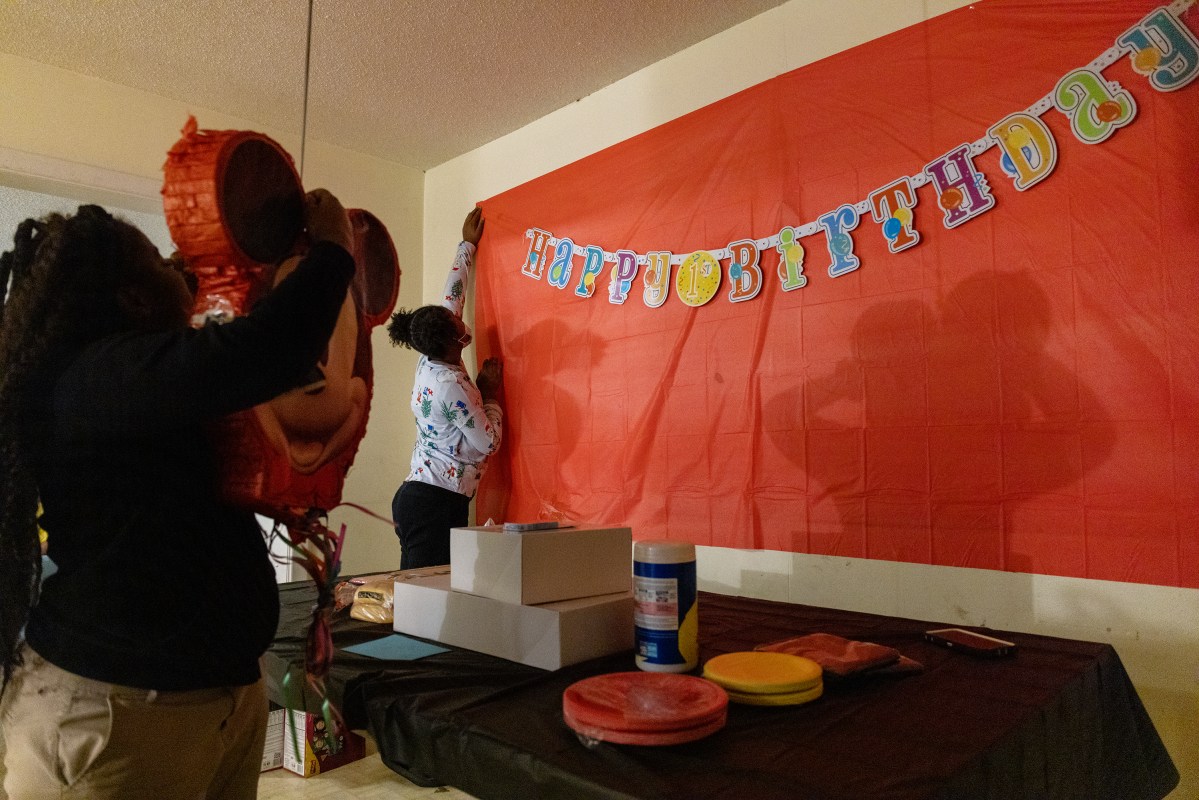

HEIDELBERG – It’s 1 a.m. and Heidelberg native Courtney Darby, a mother of four, is sound asleep in her room with part of her leg wrapped in a cast due to a broken ankle. She is suddenly awakened by the sound of her 8-month-old son, R’Jay Jones, crying.

Her daughter, Deysha Ransom, 13, who is sleeping in the room next door, wakes up and springs into action. She brings R’Jay to Darby, who breastfeeds him until he falls asleep. Deysha returns R’Jay to his room, and everyone goes back to sleep.

April-May

Darby relies heavily on her daughter, who is now 14, to help with her son since she broke her ankle in May when R’Jay was 5 months old.

“My oldest daughter is the real MVP,” Darby said. “She does a lot because she understands my issues. During that time, it’s like she was experiencing what it was like being a mother.”

The accident happened when she was getting out of her SUV to go to work. The side step bar didn’t extend as usual, and her foot landed hard on the ground, twisting her ankle. She was taken to the hospital, where her ankle was treated and wrapped in a cast.

She went to surgery for pins and a plate to be placed in her ankle several days later on a Monday. The following Friday, she went to her doctor in Laurel, and she told him she was in extreme pain.

“He said it was normal,” Darby said.

June

The following week, on June 3, she went back to the doctor to tell him about the continued pain and how tight the cast was on her ankle.

“When they took the cast off, the doctor noticed drainage in my ankle,” she said. She left with a prescription for antibiotics.

But the pain medicine she got at the hospital was not giving her any relief.

“I went through pain that I never imagined,” Darby said.

Her mom, who is a nurse, noticed that the pain was abnormal. They called the hospital several times a week seeking answers. During a visit on July 15, the doctor denied her pain medication, citing the laws surrounding narcotics.

Tears began to roll down her cheek, and her voice cracked as she told him about her pain – including that it was so severe, she considered ending her life.

She went to the doctor about six times before she was finally diagnosed in early August with osteomyelitis, an inflammation in her bone that resulted in infection.Luckily, she was diagnosed and treated around the time she was expected back at her job as a teacher at Bay Springs High School.

July

Before her ankle injury, she dealt with postpartum depression. She started to receive counseling about three months after giving birth to R’Jay.

“That was a fight with the devil,” Darby said. “Sometimes it was very much so getting the best of me. I didn’t want to get out of bed or comb my hair.”

She was breastfeeding, so she had to push through, she said.

In January, right after giving birth to R’Jay, she received a letter stating that her Medicaid coverage would stop in February. Then, Medicaid sent another letter saying it would be reinstated due to the COVID-19 public health emergency. She had secondary insurance through her job as well.

September

But even with Medicaid and her insurance, she still received medical bills that amounted to thousands of dollars.

“I don’t understand why I have to pay this much money out of pocket when I have Medicaid coverage and secondary insurance,” Darby said.

Darby’s story isn’t unique. She is one of many women in Mississippi who feels she is being pulled close to the ground.

Specifically, Black women in the state deal with more health disparities than any other state in the country. A recent report from the state health department showed Black women in Mississippi are four times more likely to die in childbirth than their white counterparts.

The state has also not extended postpartum Medicaid coverage for women as most other states have done.

This is Darby’s story.

October -December

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

New Stage’s ‘Little Women’ musical opens aptly in Women’s History Month

Ties that bind, not lines that divide, at the heart of “Little Women” are what make Louisa May Alcott’s beloved novel such an enduring classic. More than a century and a half since its 1868 publication, the March sisters’ coming-of-age tale continues to resonate in fresh approaches, say cast and crew in a musical version opening this week at New Stage Theatre in Jackson, Mississippi.

“Little Women, The Broadway Musical” adds songs to Alcott’s story of the four distinct March sisters — traditional, lovely Meg, spirited tomboy and writer Jo, quiet and gentle Beth, and artistic, pampered Amy. They are growing into young women under the watchful eye of mother Marmee as their father serves as an Army chaplain in the Civil War. “Little Women, The Broadway Musical” performances run March 25 through April 6 at New Stage Theatre.

In a serendipitous move, the production coincides with Women’s History Month in March, and has a female director at the helm — Malaika Quarterman, in her New Stage Theatre directing debut. Logistics and scheduling preferences landed the musical in March, to catch school matinees with the American classic.

The novel has inspired myriad adaptations in film, TV, stage and opera, plus literary retellings by other authors. This musical version debuted on Broadway in 2005, with music by Jason Howland, lyrics by Mindi Dickstein and book (script) by Allan Knee.

“The music in this show brings out the heart of the characters in a way that a movie or a straight play, or even the book, can’t do,” said Cameron Vipperman, whose play-within-a-play role helps illustrate the writer Jo’s growth in the story. She read the book at age 10, and now embraces how the musical dramatizes, speeds up and reconstructs the timeline for more interest and engagement.

“What a great way to introduce kids that haven’t read the book,” director Quarterman said, hitting the highlights and sending them to the pages for a deeper dive on characters they fell in love with over the two-and-a-half-hour run time.

Joy, familial warmth, love, courage, loss, grief and resilience are all threads in a story that has captivated generations and continues to find new audiences and fresh acclaim (the 2019 film adaptation by Greta Gerwig earned six Academy Award nominations).

In current contentious times, when diversity, equity and inclusion programs are being ripped out or rolled back, the poignant, women-centered narrative maintains a power to reach deep and unite.

“Stories where females support each other, instead of rip each other apart to get to the finish line — which would be the goal of getting the man or something — are very few and far between sometimes,” Quarterman said. “It’s so special because it was written so long ago, with the writer being such a strong dreamer, and dreaming big for women.

“For us to actualize it, where a female artistic producer chooses this show and believes in a brand new female director and then this person gets to empower these great, local, awesome artists — It’s just really been special to see this story and its impact ripple through generations of dreamers.” For Quarterman, a 14-year drama teacher with Jackson Public Schools active in community theater and professional regional theater, “To be able to tell this story here, for New Stage, is pretty epic for me.”

Alcott’s story is often a touchstone for young girls, and this cast of grown women finds much in the source material that they still hold dear, and that resonates in new ways.

“I relate to Jo more than any other fictional character that exists,” Kristina Swearingen said of her character, the central figure Jo March. “At different parts of my life, I have related to her in different parts of hers.”

The Alabama native, more recently of New York, recalled her “energetic, crazy, running-around-having-a-grand-old-time” youth in high school and college, then a career-driven purpose that led her, like Jo, to move to New York.

Swearingen first did this show in college, before the loss of grandparents and a major move. Now, “I know what it’s like to grieve the loss of a loved one, and to live so far away from home, and wanting to go home and be with your family but also wanting to be in a place where your career can take off. .. It hits a lot closer to home.”

As one of four sisters in real life, Frannie Dean of Flora draws on a wealth of memories in playing Beth — including her own family position as next to the youngest of the girls. She and siblings read the story together in their homeschooled childhood, assigning each other roles.

“Omigosh, this is my life,” she said, chuckling. “We would play pretend all day. … ‘Little Women’ is really sweet in that aspect, to really be able to carry my own experience with my family and bring it into the show. … It’s timeless in its nature, its warmth and what it brings to people.”

Jennifer Smith of Clinton, as March family matriarch Marmee, found her way in through a song. First introduced to Marmee’s song “Here Alone” a decade ago when starting voice lessons as an adult, she made it her own. “It became an audition piece for me. It became a dream role for me. It’s been pivotal in opening up doors for me.”

She relishes aging into this role, countering a common fear of women in the entertainment field that they may “age out” of desirable parts. “It’s just a full-circle moment for me, and I’m grateful for it.”

Quarterman fell in love with the 1969 film version she watched with her sister when they were little, adoring the family’s playfulness and stability. Amid teenage angst, she identified with the inevitable growth and change that came with siblings growing up and moving on. Being a mom brings a whole different lens.

“Seeing these little people in your life just growing up, being their own unique versions, all going through their own arc — it’s just fun, and I think that’s why you can stay connected” to the story at any life juncture, she said.

Cast member Slade Haney pointed out the rarity of a story set on a Northeastern homestead during the Civil War.

“You’re getting to see what it was like for the women whose husbands were away at war — how moms struggled, how sisters struggled. You had to make your own means. … I think both men and women can see themselves in these characters, in wanting to be independent like Jo, or like Amy wanting to have something of value that belongs to you and not just just feel like you’re passed over all the time, and Meg, to be valuable to someone else, and in Beth, for everyone to be happy and content and love each other,” Haney said.

New Stage Theatre Artistic Director Francine Reynolds drew attention, too, to the rarity of an American classic for the stage offering an abundance of women’s roles that can showcase Jackson metro’s talent pool. “We just always have so many great women,” she said, and classics — “To Kill a Mockingbird” and “Death of a Salesman,” for instance — often offer fewer parts for them, though contemporary dramas are more balanced.

Reynolds sees value in the musical’s timing and storyline. “Of course, we need to celebrate the contributions of women. This was a woman who was trying to be a writer in 1865, ’66, ’67. That’s, to me, a real trailblazing thing.

“It is important to show, this was a real person — Louisa May Alcott, personified as Jo. It’s important to hold these people up as role models for other young girls, to show that you can do this, too. You can dream your dream. You can strive to break boundaries.”

It is a key reminder of advancements that may be threatened. “We’ve made such strides,” Reynolds said, “and had so many great programs to open doors for people, that I feel like those doors are going to start closing, just because of things you are allowed to say and things you aren’t allowed.”

For tickets, $50 (discounts for seniors, students, military), visit www.newstagetheatre.com or the New Stage Theatre box office, or call 601-948-3533.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

Rolling Fork – 2 Years Later

Tracy Harden stood outside her Chuck’s Dairy Bar in Rolling Fork, teary eyed, remembering not the EF-4 tornado that nearly wiped the town off the map two years before. Instead, she became emotional, “even after all this time,” she said, thinking of the overwhelming help people who’d come from all over selflessly offered.

“We’re back now, she said, smiling. “People have been so kind.”

“I stepped out of that cooler two years ago and saw everything, and I mean, everything was just… gone,” she said, her voice trailing off. “My God, I thought. What are we going to do now? But people came and were so giving. It’s remarkable, and such a blessing.”

“And to have another one come on almost the exact date the first came,” she said, shaking her head. “I got word from these young storm chasers I’d met. He told me they were tracking this one, and it looked like it was coming straight for us in Rolling Fork.”

“I got up and went outside.”

“And there it was!”

“I cannot tell you what went through me seeing that tornado form in the sky.”

The tornado that touched down in Rolling Fork last Sunday did minimal damage and claimed no lives.

Horns honk as people travel along U.S. 61. Harden smiles and waves.

She heads back into her restaurant after chatting with friends to resume grill duties as people, some local, some just passing through town, line up for burgers and ice cream treats.

Rolling Fork is mending, slowly. Although there is evidence of some rebuilding such as new homes under construction, many buildings like the library and post office remain boarded up and closed. A brutal reminder of that fateful evening two years ago.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

Remembering Big George Foreman and a poor guy named Pedro

George Foreman, surely one of the world’s most intriguing and transformative sports figures of the 20th century, died over the weekend at the age of 76. Please indulge me a few memories.

This was back when professional boxing was in its heyday. Muhammad Ali was heavyweight champion of the world for a second time. The lower weight divisions featured such skilled champions and future champs as Alex Arugello, Roberto “Hands of Stone” Duran, Tommy “Hit Man” Hearns and Sugar Ray Leonard.

Boxing was front page news all over the globe. Indeed, Ali was said to be the most famous person in the world and had stunned the boxing world by stopping the previously undefeated Foreman in an eighth round knockout in Kinshasa, Zaire, in October of 1974. Foreman, once an Olympic gold medalist at age 19, had won his previous 40 professional fights and few had lasted past the second round. Big George, as he was known, packed a fearsome punch.

My dealings with Foreman began in January of 1977, roughly 27 months after his Ali debacle with Foreman in the middle of a boxing comeback. At the time, I was the sports editor of my hometown newspaper in Hattiesburg when the news came that Foreman was going to fight a Puerto Rican professional named Pedro Agosto in Pensacola, just three hours away.

Right away, I applied for press credentials and was rewarded with a ringside seats at the Pensacola Civic Center. I thought I was going to cover a boxing match. It turned out more like an execution.

The mismatch was evident from the pre-fight introductions. Foreman towered over the 5-foot, 11-inch Agosto. Foreman had muscles on top of muscles, Agosto not so much. When they announced Agosto weighed 205 pounds, the New York sports writer next to me wise-cracked, “Yeah, well what is he going to weigh without his head?”

It looked entirely possible we might learn.

Foreman toyed with the smaller man for three rounds, almost like a full-grown German shepherd dealing with a tiny, yapping Shih Tzu. By the fourth round, Big George had tired of the yapping. With punches that landed like claps of thunder, Foreman knocked Agosto down three times. Twice, Agosto struggled to his feet after the referee counted to nine. Nearly half a century later I have no idea why Agosto got up. Nobody present– or the national TV audience – would have blamed him for playing possum. But, no, he got up the second time and stumbled over into the corner of the ring right in front of me. And that’s where he was when Foreman hit him with an evil right uppercut to the jaw that lifted the smaller man a foot off the canvas and sprayed me and everyone in the vicinity with Agosto’s blood, sweat and snot – thankfully, no brains. That’s when the ref ended it.

It remains the only time in my sports writing career I had to buy a T-shirt at the event to wear home.

So, now, let’s move ahead 18 years to July of 1995. Foreman had long since completed his comeback by winning back the heavyweight championship. He had become a preacher. He also had become a pitch man for a an indoor grill that bore his name and would sell more than 100 million units. He was a millionaire many times over. He made far more for hawking that grill than he ever made as a fighter. He had become a beloved figure, known for his warm smile and his soothing voice. And now he was coming to Jackson to sign his biography. His publishing company called my office to ask if I’d like an interview. I said I surely would.

One day at the office, I answered my phone and the familiar voice on the other end said, “This is George Foreman and I heard you wanted to talk to me.”

I told him I wanted to talk to him about his book but first I wanted to tell him he owed me a shirt.

“A shirt?” he said. “How’s that?”

I asked him if remembered a guy named Pedro Agosto. He said he did. “Man, I really hit that poor guy,” he said.

I thought you had killed him, I said, and I then told him about all the blood and snot that ruined my shirt.

“Man, I’m sorry about that,” he said. “I’d never hit a guy like that now. I was an angry, angry man back then.”

We had a nice conversation. He told me about finding his Lord. He told me about his 12 children, including five boys, all of whom he named George.

I asked him why he would give five boys the same name.

“I never met my father until late in his life,” Big George told me. “My father never gave me nothing. So I decided I was going to give all my boys something to remember me by. I gave them all my name.”

Yes, and he named one of his girls Georgette.

We did get around to talking about his book, and you will not be surprised by its title: “By George.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

://mississippitoday.org”>Mississippi Today.

-

Local News Video7 days ago

Local News Video7 days agoLocal pharmacists advocating for passage of bill limiting control of pharmacy benefit managers

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed5 days agoFamily mourns death of 10-year-old Xavier Williams

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days agoLIVE: SpaceX NROL-69 mission launch

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days agoReport: Proposed Medicaid, SNAP cuts would cost Arkansas thousands of jobs, $1B in GDP

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago1 Dead, Officer and Bystander Hurt in Shootout | March 25, 2025 | News 19 at 9 p.m.

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed6 days agoClassmates remember college student hit by car, killed near NC State

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed4 days agoSevere storms will impact Alabama this weekend. Damaging winds, hail, and a tornado threat are al…

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed3 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed3 days agoUniversity of Alabama student detained by ICE moved to Louisiana