Mississippi Today

Mississippi moms and babies are dying. This training teaches first responders how to save their lives.

Mississippi moms and babies are dying. This training teaches first responders how to save their lives.

Matt Greer of Brookhaven was driving home from his shift at the Mississippi Center for Emergency Services, where he works as a flight nurse, when he got a call from his younger sister. A few days earlier, she had given birth to a healthy baby girl after an uncomplicated pregnancy. Now, she told him she had a headache.

He asked her to check her blood pressure: 140/90.

For most patients, that reading isn’t concerning. For a pregnant or postpartum woman, however, it’s an indication of preeclampsia. Greer told her to go to the hospital and eventually she did, getting treatment to prevent seizure and stroke.

But Greer thinks things might have gone very differently had he not completed a new training run by the Mississippi Center for Emergency Services just a few weeks before his sister called.

The STORK Program equips first responders and medical professionals without specialized obstetrics training – including emergency room doctors and nurses – to handle pregnancy and delivery complications like hypertension and hemorrhage. Doctors at the University of Mississippi Medical Center recognized that in a rural state with dwindling options for obstetrical care, women are likely to deliver outside of dedicated labor and delivery wards, and to need care from people who don’t see pregnant patients every day. So they created the STORK training.

Greer has years of experience as a nurse, and his sister is a nurse, too. But without STORK, he would not have known how to interpret her blood pressure reading.

“I would have blown it off,” he said. “Without that fresh on my mind … I would have said, ‘that’s not too bad. You’ll be alright.’”

Chronic health conditions like obesity and diabetes plus poor access to prenatal care contribute to Mississippi’s worst-in-the-nation outcomes for moms and babies, and can’t be treated during a single interaction with a health care provider. But potentially lethal hypertension and hemorrhage are not complicated to manage – if a provider knows what to watch for and what to do.

And even inside hospitals, that can be a big “if.”

“Obstetrics is most people’s kryptonite,” said Dr. Rachael Morris, associate professor of maternal fetal medicine at UMMC, who created and leads the training. “Unless you’re an obstetrician, even a well-trained E.R. physician or mid-level provider is going to tell you that you bring a pregnant lady into my E.R., and everyone’s going to freak out.”

The STORK Program’s half-day training includes lectures and simulations to change that dynamic. (STORK stands for Stabilizing OB and Neonatal Patients, Training for OB/Neonatal Emergencies, Outcome Improvements, Resource Sharing, and Kind Care for Vulnerable Families.) The training is funded with a grant from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, which also allows participants to receive a bag of supplies they can use during deliveries. The program is run by MCES, a division of UMMC that houses critical care transport services – including helicopter teams – and the state’s communications system for hospitals and first responders, Mississippi MED-COM.

“In Mississippi, infant and maternal mortality rates for people of color are among the highest in the nation and many families have to travel considerable distance to access care, creating obstetric emergencies,” said Wesley Prater, Kellogg Foundation program officer. “Our support of UMMC ensures providers across the state have the proper training to stabilize mothers and babies who need critical care.”

So far, about 150 people from around the state – a mix of registered nurses, physicians, medical residents, firefighters and paramedics – have completed the training over 11 classes since it launched in June. The team has 18 more trainings on the calendar.

With the state likely to tally an additional 5,000 births annually thanks to the abortion ban that took effect in July, obstetric services in the state are actually shrinking. The labor and delivery ward at Greenwood-Leflore Hospital closed in the fall. The Delta lost its only neonatal intensive care unit this summer. The NICU at Merit Health Central, which serves predominantly Black and low-income Jackson neighborhoods, also closed.

Already, more than half of the state’s counties are maternity care deserts: No labor and delivery ward. No OB-GYNs. No certified nurse midwives.

Women in rural areas face long drives to the nearest labor and delivery ward. Sometimes, that means they can’t make it there at all. Instead, they may give birth in an emergency room, at home while waiting for first responders to show up, or on the side of the road.

The STORK program staff hope training participants will be able to handle those situations effectively, saving lives along the way.

“These patients are going to be coming into really small hospitals and delivering or having problems,” said Dr. Tara Lewis, assistant professor of emergency medicine at UMMC and a former labor and delivery nurse.

Lewis joined the program to help tailor it to the needs of emergency room staff in small, rural hospitals.

“If providers don’t know how to make the diagnosis of what problem is going on, then they’re not going to know how to take care of them.”

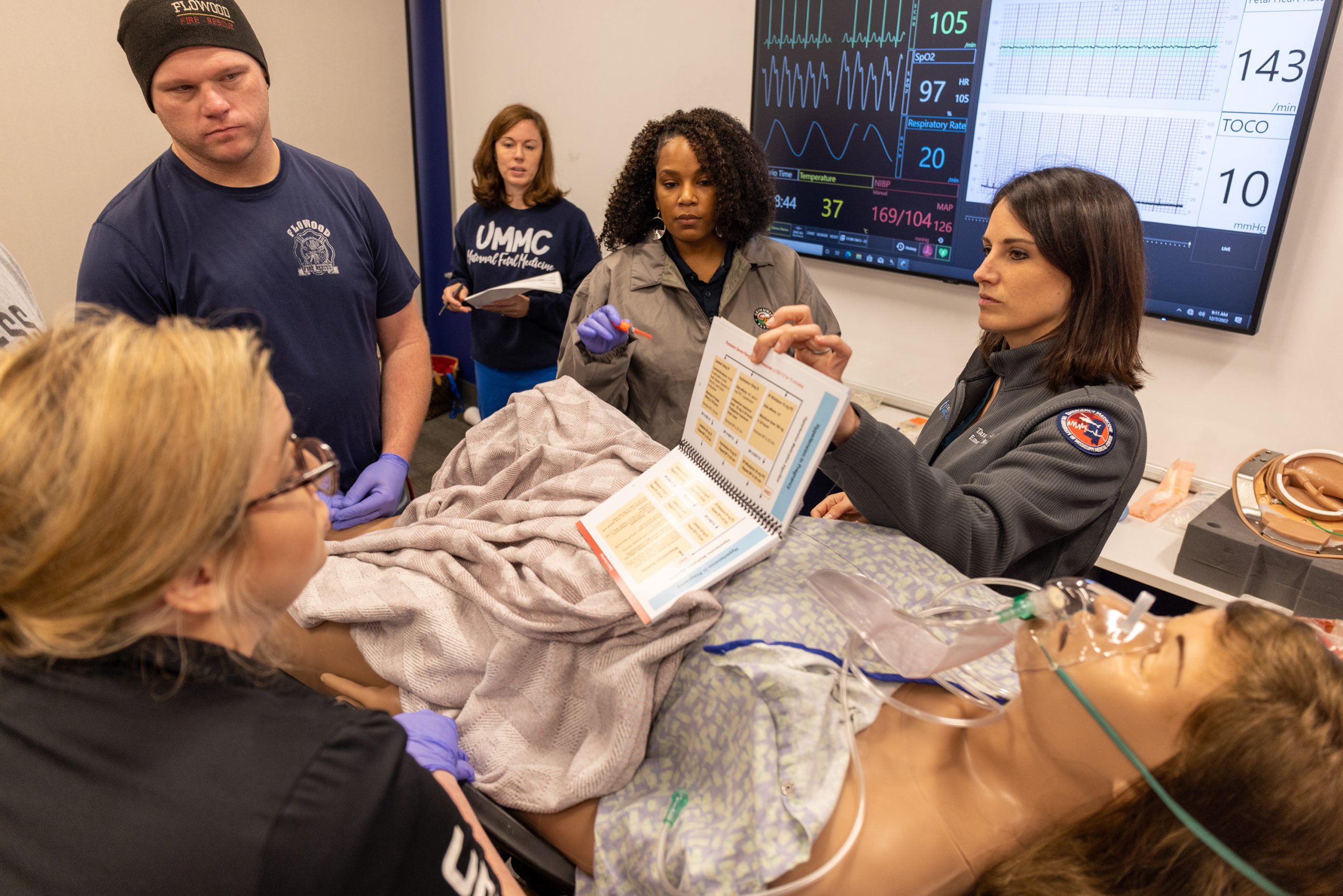

PHOTOS: First responders trained on how to deliver babies

“You look like a really good uterus,” Morris told a burly Flowood firefighter and paramedic who had joined three of his colleagues to attend a STORK training at MCES on a recent Wednesday morning.

She had just given a presentation on managing hypertension and hemorrhage, and now it was time to demonstrate how to assist during a delivery.

The paramedic held a rubber baby as Morris demonstrated how a baby’s head will generally turn to one side as it leaves the birth canal, and how to use a finger to gently loosen the umbilical cord if it has looped around the neck.

In addition to the Flowood firefighters, attendees included a pediatric emergency room nurse at UMMC, a women’s health nurse in Meridian, and an emergency room nurse at Magee General Hospital who has assisted with three deliveries in the last year alone.

“That’s a lot considering it’s a small hospital with no labor and delivery resources,” she said.

There are regular STORK trainings at MCES open to people from all over the state. But the free training is also conducted at hospitals, so participants don’t have to travel and can see how to apply what they learn where they work.

After Morris finished her presentation, Emily Wells, a nurse practitioner and member of UMMC’s neonate transport team, explained how to care for newborns in the moments after birth. Since Jan. 1 of this year, the team has transported 390 babies to higher levels of care, and participated in 20 emergency room deliveries.

She described the recent delivery of a “rest stop baby,” who was born in a Toyota Camry en route to a hospital during a cold snap.

“Cold babies die,” she said, so the team had cranked up the heat inside the car and done everything they could to keep the baby warm.

In a hospital, the baby would be placed in an incubator. But in a pinch, any kind of plastic bag – maybe one that had been used to hold supplies now in use – could be placed around the baby’s body to conserve heat.

A woman had just delivered a baby at 26 weeks in her car, and now both had made it to the emergency room of their small-town hospital. She had delivered the placenta, too, but was still bleeding.

What should happen next? Half of the training participants gathered around their patient – a life-size mannequin lying on a hospital bed shouting “I’m bleeding” – and discussed what to do.

“At 26 weeks, I think the placenta abrupted,” Morris explained.

Blood trickled from the mannequin’s vagina, soaking a pad underneath her body. This was an important lesson, Leslie Cannon, now an educator with STORK after 25 years as a labor and delivery nurse, pointed out: In patients who aren’t pregnant, life-threatening hemorrhage often looks like a dramatic gush.

“Hemorrhage postpartum, it’s this trickle,” she said. “It’s a huge deal, because that trickle just keeps going.”

That’s important to keep in mind especially because it’s often not obvious when a woman is at serious risk because of bleeding.

“A young, healthy pregnant lady is going to look really good — until she’s about dead,” Morris had warned of hemorrhaging patients.

The students administered tranexamic acid to slow the bleeding.

As Morris had explained during her lecture, a student reached an arm into the uterus to sweep for pieces of retained placenta, which can cause life-threatening bleeding. (“It’s not a comfortable thing to do,” Morris warned.) Another student massaged the mannequin’s belly to cause the uterus to contract.

Eventually, the trickle slowed and stopped. Morris estimated the patient had lost a liter of blood.

Before everyone left, Morris and Wells gave out their cell phone numbers. Kace Ragan, project manager for STORK, explained that participants get supply bags that include QR codes they can scan to request refills — as long as the grant funding holds out — and report their experiences during deliveries.

Morris urged the attendees to text or call her with questions any time. Morris treats some of the most challenging pregnancies in the state and serves as obstetric COVID director at UMMC, meaning she’s spent the last two years witnessing devastating loss.

And yet, she told the training participants, she has “the luxury” of working in a hospital with plenty of resources and specialized training.

“Y’all are in the trenches doing things that I have to do, too, but with so much less,” she said.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Mississippi Legislature approves DEI ban after heated debate

Mississippi lawmakers have reached an agreement to ban diversity, equity and inclusion programs and a list of “divisive concepts” from public schools across the state education system, following the lead of numerous other Republican-controlled states and President Donald Trump’s administration.

House and Senate lawmakers approved a compromise bill in votes on Tuesday and Wednesday. It will likely head to Republican Gov. Tate Reeves for his signature after it clears a procedural motion.

The agreement between the Republican-dominated chambers followed hours of heated debate in which Democrats, almost all of whom are Black, excoriated the legislation as a setback in the long struggle to make Mississippi a fairer place for minorities. They also said the bill could bog universities down with costly legal fights and erode academic freedom.

Democratic Rep. Bryant Clark, who seldom addresses the entire House chamber from the podium during debates, rose to speak out against the bill on Tuesday. He is the son of the late Robert Clark, the first Black Mississippian elected to the state Legislature since the 1800s and the first Black Mississippian to serve as speaker pro tempore and preside over the House chamber since Reconstruction.

“We are better than this, and all of you know that we don’t need this with Mississippi history,” Clark said. “We should be the ones that say, ‘listen, we may be from Mississippi, we may have a dark past, but you know what, we’re going to be the first to stand up this time and say there is nothing wrong with DEI.'”

Legislative Republicans argued that the measure — which will apply to all public schools from the K-12 level through universities — will elevate merit in education and remove a list of so-called “divisive concepts” from academic settings. More broadly, conservative critics of DEI say the programs divide people into categories of victims and oppressors and infuse left-wing ideology into campus life.

“We are a diverse state. Nowhere in here are we trying to wipe that out,” said Republican Sen. Tyler McCaughn, one of the bill’s authors. “We’re just trying to change the focus back to that of excellence.”

The House and Senate initially passed proposals that differed in who they would impact, what activities they would regulate and how they aim to reshape the inner workings of the state’s education system. Some House leaders wanted the bill to be “semi-vague” in its language and wanted to create a process for withholding state funds based on complaints that almost anyone could lodge. The Senate wanted to pair a DEI ban with a task force to study inefficiencies in the higher education system, a provision the upper chamber later agreed to scrap.

The concepts that will be rooted out from curricula include the idea that gender identity can be a “subjective sense of self, disconnected from biological reality.” The move reflects another effort to align with the Trump administration, which has declared via executive order that there are only two sexes.

The House and Senate disagreed on how to enforce the measure but ultimately settled on an agreement that would empower students, parents of minor students, faculty members and contractors to sue schools for violating the law.

People could only sue after they go through an internal campus review process and a 25-day period when schools could fix the alleged violation. Republican Rep. Joey Hood, one of the House negotiators, said that was a compromise between the chambers. The House wanted to make it possible for almost anyone to file lawsuits over the DEI ban, while Senate negotiators initially bristled at the idea of fast-tracking internal campus disputes to the legal system.

The House ultimately held firm in its position to create a private cause of action, or the right to sue, but it agreed to give schools the ability to conduct an investigative process and potentially resolve the alleged violation before letting people sue in chancery courts.

“You have to go through the administrative process,” said Republican Sen. Nicole Boyd, one of the bill’s lead authors. “Because the whole idea is that, if there is a violation, the school needs to cure the violation. That’s what the purpose is. It’s not to create litigation, it’s to cure violations.”

If people disagree with the findings from that process, they could also ask the attorney general’s office to sue on their behalf.

Under the new law, Mississippi could withhold state funds from schools that don’t comply. Schools would be required to compile reports on all complaints filed in response to the new law.

Trump promised in his 2024 campaign to eliminate DEI in the federal government. One of the first executive orders he signed did that. Some Mississippi lawmakers introduced bills in the 2024 session to restrict DEI, but the proposals never made it out of committee. With the national headwinds at their backs and several other laws in Republican-led states to use as models, Mississippi lawmakers made plans to introduce anti-DEI legislation.

The policy debate also unfolded amid the early stages of a potential Republican primary matchup in the 2027 governor’s race between State Auditor Shad White and Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann. White, who has been one of the state’s loudest advocates for banning DEI, had branded Hosemann in the months before the 2025 session “DEI Delbert,” claiming the Senate leader has stood in the way of DEI restrictions passing the Legislature.

During the first Senate floor debate over the chamber’s DEI legislation during this year’s legislative session, Hosemann seemed to be conscious of these political attacks. He walked over to staff members and asked how many people were watching the debate live on YouTube.

As the DEI debate cleared one of its final hurdles Wednesday afternoon, the House and Senate remained at loggerheads over the state budget amid Republican infighting. It appeared likely the Legislature would end its session Wednesday or Thursday without passing a $7 billion budget to fund state agencies, potentially threatening a government shutdown.

“It is my understanding that we don’t have a budget and will likely leave here without a budget. But this piece of legislation …which I don’t think remedies any of Mississippi’s issues, this has become one of the top priorities that we had to get done,” said Democratic Sen. Rod Hickman. “I just want to say, if we put that much work into everything else we did, Mississippi might be a much better place.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

House gives Senate 5 p.m. deadline to come to table, or legislative session ends with no state budget

The House on Wednesday attempted one final time to revive negotiations between it and the Senate over passing a state budget.

Otherwise, the two Republican-led chambers will likely end their session without funding government services for the next fiscal year and potentially jeopardize state agencies.

The House on Wednesday unanimously passed a measure to extend the legislative session and revive budget bills that had died on legislative deadlines last weekend.

House Speaker Jason White said he did not have any prior commitment that the Senate would agree to the proposal, but he wanted to extend one last offer to pass the budget. White, a Republican from West, said if he did not hear from the Senate by 5 p.m. on Wednesday, his chamber would end its regular session.

“The ball is in their court,” White said of the Senate. “Every indication has been that they would not agree to extend the deadlines for purposes of doing the budget. I don’t know why that is. We did it last year, and we’ve done it most years.”

But it did not appear likely Wednesday afternoon that the Senate would comply.

The Mississippi Legislature has not left Jackson without setting at least most of the state budget since 2009, when then Gov. Haley Barbour had to force them back to set one to avoid a government shutdown.

The House measure to extend the session is now before the Senate for consideration. To pass, it would require a two-thirds majority vote of senators. But that might prove impossible. Numerous senators on both sides of the aisle vowed to vote against extending the current session, and Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann who oversees the chamber said such an extension likely couldn’t pass.

Senate leadership seemed surprised at the news that the House passed the resolution to negotiate a budget, and several senators earlier on Wednesday made passing references to ending the session without passing a budget.

“We’ll look at it after it passes the full House,” Senate President Pro Tempore Dean Kirby said.

The House and Senate, each having a Republican supermajority, have fought over many issues since the legislative session began early January.

But the battle over a tax overhaul plan, including elimination of the state individual income tax, appeared to cause a major rift. Lawmakers did pass a tax overhaul, which the governor has signed into law, but Senate leaders cried foul over how it passed, with the House seizing on typos in the Senate’s proposal that accidentally resembled the House’s more aggressive elimination plan.

The Senate had urged caution in eliminating the income tax, and had economic growth triggers that would have likely phased in the elimination over many years. But the typos essentially negated the triggers, and the House and governor ran with it.

The two chambers have also recently fought over the budget. White said he communicated directly with Senate leaders that the House would stand firm on not passing a budget late in the session.

But Senate leaders said they had trouble getting the House to meet with them to haggle out the final budget.

On the normally scheduled “conference weekend” with a deadline to agree to a budget last Saturday, the House did not show, taking the weekend off. This angered Hosemann and the Senate. All the budget bills died, requiring a vote to extend the session, or the governor forcing them into a special session.

If the Legislature ends its regular session without adopting a budget, the only option to fund state agencies before their budgets expire on June 30 is for Gov. Tate Reeves to call lawmakers back into a special session later.

“There really isn’t any other option (than the governor calling a special session),” Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann previously said.

If Reeves calls a special session, he gets to set the Legislature’s agenda. A special session call gives an otherwise constitutionally weak Mississippi governor more power over the Legislature.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Amount of federal cuts to health agencies doubles

Cuts to public health and mental health funding in Mississippi have doubled – reaching approximately $238 million – since initial estimates last week, when cancellations to federal grants allocated for COVID-19 pandemic relief were first announced.

Slashed funding to the state’s health department will impact community health workers, planned improvements to the public health laboratory, the agency’s ability to provide COVID-19 vaccinations and preparedness efforts for emerging pathogens, like H5 bird flu.

The grant cancellations, which total $230 million, will not be catastrophic for the agency, State Health Officer Dr. Daniel Edney told members of the Mississippi House Democratic Caucus at the Capitol April 1.

But they will set back the agency, which is still working to recover after the COVID-19 pandemic decimated its workforce and exposed “serious deficiencies” in the agency’s data collection and management systems.

The cuts will have a more significant impact on the state’s economy and agency subgrantees, who carry out public health work on the ground with health department grants, he said.

“The agency is okay. But I’m very worried about all of our partners all over the state,” Edney told lawmakers.

The health department was forced to lay off 17 contract workers as a result of the grant cancellations, though Edney said he aims to rehire them under new contracts.

Other positions funded by health department grants are in jeopardy. Two community health workers at Back Bay Mission, a nonprofit that supports people living in poverty in Biloxi, were laid off as a result of the cuts, according to WLOX. It’s unclear how many more community health workers, who educate and help people access health care, have been impacted statewide.

The department was in the process of purchasing a comprehensive data management system before the cuts and has lost the ability to invest in the Mississippi Public Health Laboratory, he said. The laboratory performs environmental and clinical testing services that aid in the prevention and control of disease.

The agency has worked to reduce its dependence on federal funds, Edney said, which will help it weather the storm. Sixty-six percent of the department’s budget is federally funded.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention pulled back $11.4 billion in funding to state health departments nationwide last week. The funding was originally allocated by Congress for testing and vaccination against the coronavirus as part of COVID-19 relief legislation, and to address health disparities in high-risk and underserved populations. An additional $1 billion from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration was also terminated.

“The COVID-19 pandemic is over, and HHS will no longer waste billions of taxpayer dollars responding to a non-existent pandemic that Americans moved on from years ago,” the Department of Health and Human Services Director of Communications Andrew Nixon said in a statement.

HHS did not respond to questions from Mississippi Today about the cuts in Mississippi.

Democratic attorneys general and governors in 23 states filed a lawsuit against the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Tuesday, arguing that the sudden cancellation of the funding was unlawful and seeking injunctive relief to halt the cuts. Mississippi did not join the suit.

Mental health cuts

The Department of Mental Health received about $7.5 million in cuts to federal grants from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Over half of the cuts were to community mental health centers, and supported alcohol and drug treatment services for people who can not afford treatment, housing services for parenting and pregnant women and their children, and prevention services.

The cuts could result in reduced beds at community mental health centers, Phaedre Cole, the director of Life Help and President of Mississippi Association of Community Mental Health Centers, told lawmakers April 1.

Community mental health centers in Mississippi are already struggling to keep their doors open. Four centers in the state have closed since 2012, and a third have an imminent to high risk of closure, Cole told legislators at a hearing last December.

“We are facing a financial crisis that threatens our ability to maintain our mission,” she said Dec. 5.

Cuts to the department will also impact diversion coordinators, who are charged with reducing recidivism of people with serious mental illness to the state’s mental health hospital, a program for first-episode psychosis, youth mental health court funding, school-aged mental health programs and suicide response programs.

The Department of Mental Health hopes to reallocate existing funding from alcohol tax revenue and federal block grant funding to discontinued programs.

The agency posted a list of all the services that have received funding cuts. The State Department of Health plans to post such a list, said spokesperson Greg Flynn.

Health leaders have expressed fear that there could be more funding cuts coming.

“My concern is that this is the beginning and not the end,” said Edney.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

-

Mississippi Today1 day ago

Mississippi Today1 day agoPharmacy benefit manager reform likely dead

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days agoSevere storms will impact Alabama this weekend. Damaging winds, hail, and a tornado threat are al…

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days agoUniversity of Alabama student detained by ICE moved to Louisiana

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed4 days agoTornado watch, severe thunderstorm warnings issued for Oklahoma

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed6 days agoA little early morning putting at the PGA Tour Superstore

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Virginia News Feed6 days agoYoungkin removes Ellis, appoints Cuccinelli to UVa board | Virginia

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed7 days agoPeanut farmer wants Florida water agency to swap forest land

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Georgia News Feed4 days agoGeorgia road project forcing homeowners out | FOX 5 News