Mississippi Today

Delta State has an enrollment problem. So far, no one’s been able to solve it.

Delta State has an enrollment problem. So far, no one’s been able to solve it.

For much of its 98-year existence, Delta State University enjoyed prosperous growth, educating more and more students in pursuit of becoming the “educational and cultural center” of the Mississippi Delta.

But in the last eight years, enrollment has plummeted at the regional college in Bolivar County faster than at any other public university in Mississippi. Headcount has dropped 29% percent since 2014, with just 2,556 students enrolled this year, raising questions about Delta State’s ability to meet its mission and provide higher education to a region that’s rapidly losing population.

Administrators have tried – and so far, largely failed – to reverse the decline. Enrollment dropped all but three years under the university’s former president, William LaForge. Over the summer, the Institutions of Higher Learning Board of Trustees suddenly removed him, citing the lack of improvement in the university’s financial and enrollment metrics. The board is now on the hunt for Delta State’s next leader with the goal of filling the position in spring 2023.

Whoever takes the helm will face significant challenges. Years of plummeting enrollment, along with deep cuts to state funding, have strained Delta State’s budget. This has forced the administration to cut programs, layoff faculty and staff, and delay much-needed maintenance and repairs. The pandemic hasn’t helped.

And it’s unclear if Delta State’s two biggest budgetary strategies — raising tuition and cutting institutional scholarships — are even working or simply making the university unaffordable for the very community it’s supposed to serve.

The administration knows that’s a possibility. In 2019, the former provost warned that increasing tuition “still doesn’t help cover the increasing cost of expenses due to a downward enrollment trend,” according to meeting minutes.

“Delta State may soon reach the saturation point of how much tuition Delta area students can afford to pay,” he told the president’s cabinet.

In 2014, tuition at Delta State cost $6,012 a year before room and board. Now, it’s up to $8,435, a quarter of the median household income in Bolivar County.

Delta State is also looking to hire a director of admissions, a search it closed in August 2022 because it was unsatisfied with the applicants.

Eddie Lovin, the vice president of student affairs, is overseeing enrollments in the meantime. In an email, he did not say if the administration thinks Delta State has reached the forewarned “saturation point” yet but wrote that “affordability is always a concern for all students, not just Delta students.”

Even though headcount declined again this fall, Lovin told Mississippi Today in an interview that he is “cautiously optimistic” enrollment will improve by 2024, citing an increase in the numbers of freshmen, transfer students and re-admitted students compared to last year.

The community is less sure. Last month, IHL trustees hosted a listening session on campus to gather input on the presidential search. The board also asked attendees to fill out an online survey. The majority of the 97 anonymous respondents identified enrollment as the biggest challenge facing Delta State. In written feedback, many said they wanted the next president to have a plan to bring more students to campus – even if that means recruiting beyond the Delta.

“How can we recapture the DSU of old and drive students from all over the state not just the Delta to DSU?” one respondent submitted.

Delta State has long had a complicated relationship with the region it serves. The historically white college was the last public university in the state to admit Black students in 1967.

While Delta State now enrolls a far higher percentage of Black students than the University of Mississippi or Mississippi State University, its demographics don’t line up with the Delta’s. In 2020, 33% of students at Delta State were Black and 55% were white, according to federal data – a near inversion of the demographics of Bolivar County, which is 65% Black and 33% white.

In 2013, the former president, LaForge, said he would focus on recruiting — he vowed that on his first day on the job, he would personally visit all the high schools in Cleveland. He also promised to fix the budget.

“For too long, Delta State’s expenses have continued to rise while enrollment has decreased,” he said at his first convocation in 2014. “Both those trains have to stop, and we are committed to halting both and turning them in the right direction.”

LaForge had to repeatedly reduce the budget, often by $1 million or more. He closed the university’s golf course at the recommendation of his cabinet and shuttered a slew of programs from athletic training to journalism.

In 2000, Delta State received roughly $21 million in state appropriations. If state funding had kept pace with inflation, the university would have received about $36 million from the Legislature this fiscal year. Instead, it got $20 million.

These state budget cuts have hamstrung the administration’s ability to fund new programs or strategies to increase enrollment. But there were tactics the university could have pursued without more funding.

At a meeting in July 2015, the former dean of enrollment management, Debbie Heslep, told cabinet members that the university needed an enrollment plan crafted with input from the whole campus.

The plan should be led by a faculty member, not admissions, Heslep said, and provide a “clear direction and a unified decision on where to take our enrollment management efforts” like targeting National Merit semi-finalists, emphasizing particular majors, or increasing scholarships.

It’s unclear from the meeting minutes if that ever happened. Interim Director of Communications Holly Ray told Mississippi Today via email that “Admissions has undergone restructuring quite a few times since then, so there isn’t any one person who was there during that time to speak to it.”

By 2018, meeting minutes show the administration discussing how dire the financial situation had become. That July, Vice President for Finance and Administration James Rutledge told cabinet members there were three ways the university could improve its cash on hand: delaying infrastructure repairs, increasing tuition and cutting scholarships.

Each strategy, Rutledge warned, came with a “caveat … that shows it will be damaging to the university,” according to minutes.

“IHL Commissioner Al Rankins has seen the Financial Sustainability report, and he knows our three strategies can’t be accomplished without terrible consequences,” Rutledge told the cabinet.

The reason Delta State was considering pursuing that latter strategy — reducing scholarships — was somewhat ironic. The university had routinely overspent its scholarship budget by $1 million, largely because of increased tuition.

For students, the reduction in scholarships can mean they’re taking on more debt to go to college.

At Delta State, 60% of students take out federal loans to attend, according to the U.S. Department of Education’s College Scorecard. After graduation, the median debt is a little over $21,000 – a significant amount compared to median earnings of about $37,000.

It remains to be seen if these strategies will meaningfully improve the school’s budget. The influx of federal dollars during the pandemic has helped Delta State stay afloat the last two years. And while the university’s cash on hand increased to 40 days in 2020 – the highest in 10 years – that’s still nowhere near IHL’s goal of 90 days.

But Delta State has a plan to improve enrollment now. At LaForge’s direction, Lovin, the vice president of student affairs, prepared one for IHL last year. The plan emphasizes recruiting in nearby high schools so that Delta State can once again “own its own backyard” but also says the university must “expand its reach” to meet its needs.

The plan does not discuss Delta State’s affordability. Lovin said he thinks the primary reason enrollment has declined is subpar recruiting efforts, not cost.

When he took over admissions, Lovin said he learned “we hadn’t been to Cleveland High School in seven years,” he said. “It’s a block down the street.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=200076

Mississippi Today

New Stage’s ‘Little Women’ musical opens aptly in Women’s History Month

Ties that bind, not lines that divide, at the heart of “Little Women” are what make Louisa May Alcott’s beloved novel such an enduring classic. More than a century and a half since its 1868 publication, the March sisters’ coming-of-age tale continues to resonate in fresh approaches, say cast and crew in a musical version opening this week at New Stage Theatre in Jackson, Mississippi.

“Little Women, The Broadway Musical” adds songs to Alcott’s story of the four distinct March sisters — traditional, lovely Meg, spirited tomboy and writer Jo, quiet and gentle Beth, and artistic, pampered Amy. They are growing into young women under the watchful eye of mother Marmee as their father serves as an Army chaplain in the Civil War. “Little Women, The Broadway Musical” performances run March 25 through April 6 at New Stage Theatre.

In a serendipitous move, the production coincides with Women’s History Month in March, and has a female director at the helm — Malaika Quarterman, in her New Stage Theatre directing debut. Logistics and scheduling preferences landed the musical in March, to catch school matinees with the American classic.

The novel has inspired myriad adaptations in film, TV, stage and opera, plus literary retellings by other authors. This musical version debuted on Broadway in 2005, with music by Jason Howland, lyrics by Mindi Dickstein and book (script) by Allan Knee.

“The music in this show brings out the heart of the characters in a way that a movie or a straight play, or even the book, can’t do,” said Cameron Vipperman, whose play-within-a-play role helps illustrate the writer Jo’s growth in the story. She read the book at age 10, and now embraces how the musical dramatizes, speeds up and reconstructs the timeline for more interest and engagement.

“What a great way to introduce kids that haven’t read the book,” director Quarterman said, hitting the highlights and sending them to the pages for a deeper dive on characters they fell in love with over the two-and-a-half-hour run time.

Joy, familial warmth, love, courage, loss, grief and resilience are all threads in a story that has captivated generations and continues to find new audiences and fresh acclaim (the 2019 film adaptation by Greta Gerwig earned six Academy Award nominations).

In current contentious times, when diversity, equity and inclusion programs are being ripped out or rolled back, the poignant, women-centered narrative maintains a power to reach deep and unite.

“Stories where females support each other, instead of rip each other apart to get to the finish line — which would be the goal of getting the man or something — are very few and far between sometimes,” Quarterman said. “It’s so special because it was written so long ago, with the writer being such a strong dreamer, and dreaming big for women.

“For us to actualize it, where a female artistic producer chooses this show and believes in a brand new female director and then this person gets to empower these great, local, awesome artists — It’s just really been special to see this story and its impact ripple through generations of dreamers.” For Quarterman, a 14-year drama teacher with Jackson Public Schools active in community theater and professional regional theater, “To be able to tell this story here, for New Stage, is pretty epic for me.”

Alcott’s story is often a touchstone for young girls, and this cast of grown women finds much in the source material that they still hold dear, and that resonates in new ways.

“I relate to Jo more than any other fictional character that exists,” Kristina Swearingen said of her character, the central figure Jo March. “At different parts of my life, I have related to her in different parts of hers.”

The Alabama native, more recently of New York, recalled her “energetic, crazy, running-around-having-a-grand-old-time” youth in high school and college, then a career-driven purpose that led her, like Jo, to move to New York.

Swearingen first did this show in college, before the loss of grandparents and a major move. Now, “I know what it’s like to grieve the loss of a loved one, and to live so far away from home, and wanting to go home and be with your family but also wanting to be in a place where your career can take off. .. It hits a lot closer to home.”

As one of four sisters in real life, Frannie Dean of Flora draws on a wealth of memories in playing Beth — including her own family position as next to the youngest of the girls. She and siblings read the story together in their homeschooled childhood, assigning each other roles.

“Omigosh, this is my life,” she said, chuckling. “We would play pretend all day. … ‘Little Women’ is really sweet in that aspect, to really be able to carry my own experience with my family and bring it into the show. … It’s timeless in its nature, its warmth and what it brings to people.”

Jennifer Smith of Clinton, as March family matriarch Marmee, found her way in through a song. First introduced to Marmee’s song “Here Alone” a decade ago when starting voice lessons as an adult, she made it her own. “It became an audition piece for me. It became a dream role for me. It’s been pivotal in opening up doors for me.”

She relishes aging into this role, countering a common fear of women in the entertainment field that they may “age out” of desirable parts. “It’s just a full-circle moment for me, and I’m grateful for it.”

Quarterman fell in love with the 1969 film version she watched with her sister when they were little, adoring the family’s playfulness and stability. Amid teenage angst, she identified with the inevitable growth and change that came with siblings growing up and moving on. Being a mom brings a whole different lens.

“Seeing these little people in your life just growing up, being their own unique versions, all going through their own arc — it’s just fun, and I think that’s why you can stay connected” to the story at any life juncture, she said.

Cast member Slade Haney pointed out the rarity of a story set on a Northeastern homestead during the Civil War.

“You’re getting to see what it was like for the women whose husbands were away at war — how moms struggled, how sisters struggled. You had to make your own means. … I think both men and women can see themselves in these characters, in wanting to be independent like Jo, or like Amy wanting to have something of value that belongs to you and not just just feel like you’re passed over all the time, and Meg, to be valuable to someone else, and in Beth, for everyone to be happy and content and love each other,” Haney said.

New Stage Theatre Artistic Director Francine Reynolds drew attention, too, to the rarity of an American classic for the stage offering an abundance of women’s roles that can showcase Jackson metro’s talent pool. “We just always have so many great women,” she said, and classics — “To Kill a Mockingbird” and “Death of a Salesman,” for instance — often offer fewer parts for them, though contemporary dramas are more balanced.

Reynolds sees value in the musical’s timing and storyline. “Of course, we need to celebrate the contributions of women. This was a woman who was trying to be a writer in 1865, ’66, ’67. That’s, to me, a real trailblazing thing.

“It is important to show, this was a real person — Louisa May Alcott, personified as Jo. It’s important to hold these people up as role models for other young girls, to show that you can do this, too. You can dream your dream. You can strive to break boundaries.”

It is a key reminder of advancements that may be threatened. “We’ve made such strides,” Reynolds said, “and had so many great programs to open doors for people, that I feel like those doors are going to start closing, just because of things you are allowed to say and things you aren’t allowed.”

For tickets, $50 (discounts for seniors, students, military), visit www.newstagetheatre.com or the New Stage Theatre box office, or call 601-948-3533.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

Rolling Fork – 2 Years Later

Tracy Harden stood outside her Chuck’s Dairy Bar in Rolling Fork, teary eyed, remembering not the EF-4 tornado that nearly wiped the town off the map two years before. Instead, she became emotional, “even after all this time,” she said, thinking of the overwhelming help people who’d come from all over selflessly offered.

“We’re back now, she said, smiling. “People have been so kind.”

“I stepped out of that cooler two years ago and saw everything, and I mean, everything was just… gone,” she said, her voice trailing off. “My God, I thought. What are we going to do now? But people came and were so giving. It’s remarkable, and such a blessing.”

“And to have another one come on almost the exact date the first came,” she said, shaking her head. “I got word from these young storm chasers I’d met. He told me they were tracking this one, and it looked like it was coming straight for us in Rolling Fork.”

“I got up and went outside.”

“And there it was!”

“I cannot tell you what went through me seeing that tornado form in the sky.”

The tornado that touched down in Rolling Fork last Sunday did minimal damage and claimed no lives.

Horns honk as people travel along U.S. 61. Harden smiles and waves.

She heads back into her restaurant after chatting with friends to resume grill duties as people, some local, some just passing through town, line up for burgers and ice cream treats.

Rolling Fork is mending, slowly. Although there is evidence of some rebuilding such as new homes under construction, many buildings like the library and post office remain boarded up and closed. A brutal reminder of that fateful evening two years ago.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Mississippi Today

Remembering Big George Foreman and a poor guy named Pedro

George Foreman, surely one of the world’s most intriguing and transformative sports figures of the 20th century, died over the weekend at the age of 76. Please indulge me a few memories.

This was back when professional boxing was in its heyday. Muhammad Ali was heavyweight champion of the world for a second time. The lower weight divisions featured such skilled champions and future champs as Alex Arugello, Roberto “Hands of Stone” Duran, Tommy “Hit Man” Hearns and Sugar Ray Leonard.

Boxing was front page news all over the globe. Indeed, Ali was said to be the most famous person in the world and had stunned the boxing world by stopping the previously undefeated Foreman in an eighth round knockout in Kinshasa, Zaire, in October of 1974. Foreman, once an Olympic gold medalist at age 19, had won his previous 40 professional fights and few had lasted past the second round. Big George, as he was known, packed a fearsome punch.

My dealings with Foreman began in January of 1977, roughly 27 months after his Ali debacle with Foreman in the middle of a boxing comeback. At the time, I was the sports editor of my hometown newspaper in Hattiesburg when the news came that Foreman was going to fight a Puerto Rican professional named Pedro Agosto in Pensacola, just three hours away.

Right away, I applied for press credentials and was rewarded with a ringside seats at the Pensacola Civic Center. I thought I was going to cover a boxing match. It turned out more like an execution.

The mismatch was evident from the pre-fight introductions. Foreman towered over the 5-foot, 11-inch Agosto. Foreman had muscles on top of muscles, Agosto not so much. When they announced Agosto weighed 205 pounds, the New York sports writer next to me wise-cracked, “Yeah, well what is he going to weigh without his head?”

It looked entirely possible we might learn.

Foreman toyed with the smaller man for three rounds, almost like a full-grown German shepherd dealing with a tiny, yapping Shih Tzu. By the fourth round, Big George had tired of the yapping. With punches that landed like claps of thunder, Foreman knocked Agosto down three times. Twice, Agosto struggled to his feet after the referee counted to nine. Nearly half a century later I have no idea why Agosto got up. Nobody present– or the national TV audience – would have blamed him for playing possum. But, no, he got up the second time and stumbled over into the corner of the ring right in front of me. And that’s where he was when Foreman hit him with an evil right uppercut to the jaw that lifted the smaller man a foot off the canvas and sprayed me and everyone in the vicinity with Agosto’s blood, sweat and snot – thankfully, no brains. That’s when the ref ended it.

It remains the only time in my sports writing career I had to buy a T-shirt at the event to wear home.

So, now, let’s move ahead 18 years to July of 1995. Foreman had long since completed his comeback by winning back the heavyweight championship. He had become a preacher. He also had become a pitch man for a an indoor grill that bore his name and would sell more than 100 million units. He was a millionaire many times over. He made far more for hawking that grill than he ever made as a fighter. He had become a beloved figure, known for his warm smile and his soothing voice. And now he was coming to Jackson to sign his biography. His publishing company called my office to ask if I’d like an interview. I said I surely would.

One day at the office, I answered my phone and the familiar voice on the other end said, “This is George Foreman and I heard you wanted to talk to me.”

I told him I wanted to talk to him about his book but first I wanted to tell him he owed me a shirt.

“A shirt?” he said. “How’s that?”

I asked him if remembered a guy named Pedro Agosto. He said he did. “Man, I really hit that poor guy,” he said.

I thought you had killed him, I said, and I then told him about all the blood and snot that ruined my shirt.

“Man, I’m sorry about that,” he said. “I’d never hit a guy like that now. I was an angry, angry man back then.”

We had a nice conversation. He told me about finding his Lord. He told me about his 12 children, including five boys, all of whom he named George.

I asked him why he would give five boys the same name.

“I never met my father until late in his life,” Big George told me. “My father never gave me nothing. So I decided I was going to give all my boys something to remember me by. I gave them all my name.”

Yes, and he named one of his girls Georgette.

We did get around to talking about his book, and you will not be surprised by its title: “By George.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

://mississippitoday.org”>Mississippi Today.

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days agoFamily mourns death of 10-year-old Xavier Williams

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago1 Dead, Officer and Bystander Hurt in Shootout | March 25, 2025 | News 19 at 9 p.m.

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days agoSevere storms will impact Alabama this weekend. Damaging winds, hail, and a tornado threat are al…

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed4 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed4 days agoUniversity of Alabama student detained by ICE moved to Louisiana

-

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed6 days agoSeafood testers find Shreveport restaurants deceiving customers with foreign shrimp

-

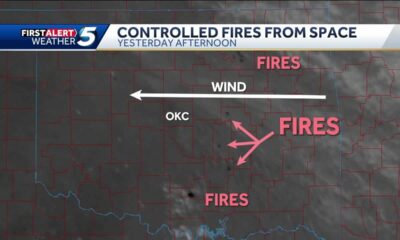

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed3 days ago

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed3 days agoTornado watch, severe thunderstorm warnings issued for Oklahoma

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed6 days agoWhy are Oklahomans smelling smoke Wednesday morning?

-

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed6 days agoRoane County Schools installing security film on windows to protect students